2010 Immigration detention on Christmas Island

Download in PDF [1.3 MB]

Download in Word [2.9 MB]

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Background

- 3 Summary

- 4 Recommendations

- 5 Overview: immigration detention on Christmas Island

PART B: Key policy and processing developments

- 6 Increasing detainee numbers and transfers to mainland detention facilities

- 7 Excision and offshore processing

- 8 Suspension of processing

- 9 Length of detention

- 10 Potential for indefinite or arbitrary detention

- 11 Under-utilisation of the Community Detention system

PART C: Children in detention on Christmas Island

- 12 Mandatory detention of children on Christmas Island

- 13 Detention placement for children on Christmas Island

- 14 Conditions and services for children in the Construction Camp

- 15 Child welfare and protection responsibilities

- 16 Unaccompanied minors in detention

PART D: Conditions and services in detention

- 17 Detention infrastructure and environment

- 18 Staff treatment

- 19 Access to health and mental health care

- 20 Provision of information to people in detention

- 21 Access to communication

- 22 Recreation and education

- 23 Religion

Part E: Monitoring conditions of detention on Christmas Island

PART A: Introductory sections

1 Introduction

This report contains a summary of observations made by the Australian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) during its 2010 visit to the immigration detention facilities on Christmas Island.

Three Commission staff members visited Christmas Island from 28 May to 3 June 2010. The purpose of the visit was to monitor conditions in immigration detention against internationally accepted human rights standards. The activities undertaken during the visit are set out in Appendix 1. This report comments on conditions at the time of the Commission’s visit. The Commission is aware that there have been developments between the time of its visit and the publication of this report.

The Commission acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) in organising and facilitating the visit, and the positive cooperation received from DIAC officers and detention service provider staff members during the visit. The Commission also thanks local representatives on Christmas Island for their willingness to spend time meeting with Commission staff.

The Commission provided a copy of this report to DIAC in advance of its publication, in order to provide DIAC with an opportunity to prepare a response. DIAC’s response is available on the Commission’s website at www.humanrights.gov.au/human_rights/immigration/

idc2010_christmas_island_response.html.

2 Background

For more than a decade, the Commission has raised significant concerns about Australia’s immigration detention system. During this time, the Commission has investigated numerous complaints from individuals in detention and conducted two national inquiries into the mandatory detention system.[1] The Commission has concluded that this system breaches fundamental human rights.[2]

Because of its concerns, the Commission undertakes a range of monitoring activities.[3] These include conducting inspections of Australia’s immigration detention facilities, with the aim of ensuring that conditions meet internationally accepted human rights standards. The relevant standards are set out in Appendix 2.

This report follows the Commission’s 2006, 2007 and 2008 annual reports on inspections of immigration detention facilities[4] and its 2009 report, Immigration detention and offshore processing on Christmas Island.[5]

The Commission’s 2009 report found that Christmas Island is not an appropriate place in which to hold people in immigration detention for a range of reasons including the nature of the detention facilities, the limited infrastructure and lack of community-based accommodation options, and the restrictions on asylum seekers’ access to essential services and support networks.[6] The Commission also expressed concerns about the ongoing excision regime and the practice of assessing the claims of asylum seekers who arrive in excised offshore places through a non-statutory process.[7]

The key recommendations of the Commission’s 2009 report included that people should not be held in immigration detention on Christmas Island; the provisions of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act) relating to excised offshore places should be repealed; and all unauthorised arrivals who make claims for asylum should have those claims assessed through the refugee status determination system that applies under the Migration Act.[8]

A range of other domestic and international organisations and experts have also raised significant concerns about the Australian Government’s policy of holding asylum seekers in detention on Christmas Island. These include Amnesty International, the Refugee Council of Australia, local religious leaders, United Nations treaty bodies and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health.[9]

Since the Commission’s 2009 visit to Christmas Island, there have been a range of significant developments – some positive and others negative. These have included an increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat and an increase in the number of people in detention on Christmas Island; the transfer of some asylum seekers to mainland detention facilities; the re-opening of the Curtin Immigration Detention Centre and the Port Augusta Immigration Residential Housing; the establishment of new ‘alternative places of detention’ on the mainland; and the suspension of processing of claims by asylum seekers from Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

The Commission’s 2010 visit to Christmas Island focused predominantly on the conditions of detention for asylum seekers. However, this report also considers some of the key policy and processing developments that have impacted on those conditions over the past year. The report focuses on areas in which there have been notable changes since the Commission’s 2009 Christmas Island visit and report.

3 Summary

Since the Commission visited Christmas Island in 2009, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people detained there. While there have been some improvements in the operation of the detention facilities, the increase in numbers has led to overcrowding and a significant deterioration in conditions for many people.

DIAC officers and staff members of detention service providers are clearly working under considerable pressures on Christmas Island, caused by a range of factors including the number of people in detention, infrastructure constraints and logistical difficulties resulting from the small size and remoteness of the island. The Commission acknowledges the efforts being made by staff to ensure that people in detention are treated appropriately despite the challenging circumstances.

During its 2010 visit, the Commission was pleased to observe and hear reports of some positive developments. These include the fact that the separation detention system is no longer used; positive reports from people in detention about most staff members; positive efforts to provide recreational activities in detention; an increase in religious support for people in detention; a new initiative of engaging some people in detention as teacher’s aides at the local school; and increased DIAC efforts to engage with the local community.

However, the Commission’s overarching concerns about the inappropriateness of holding asylum seekers in immigration detention on Christmas Island remain. The Commission’s major concerns are summarised below and discussed in further detail throughout this report.

Overarching policy concerns

- Asylum seekers who arrive by boat in an excised offshore place continue to be subjected to mandatory detention on Christmas Island, despite the fact that the Migration Act does not require this. Further, the Migration Act purports to bar them from challenging the lawfulness of their detention in the Australian courts.[10]

- Asylum seekers who arrive in an excised offshore place continue to be barred from the refugee status determination system that applies under the Migration Act. Instead, their claims are assessed through a non-statutory process governed by policy guidelines.

- The decision to suspend processing of claims by asylum seekers from Sri Lanka and Afghanistan led to the prolonged detention of a significant number of people, including children.

- More people are being held in immigration detention on Christmas Island for longer periods of time. There continues to be no set time limit on the period a person may be detained.

- Community Detention is no longer available on Christmas Island, and is barely being used on the mainland.

Detention of unaccompanied minors and families with children

- Children continue to be subjected to mandatory detention on Christmas Island, in breach of Australia’s obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

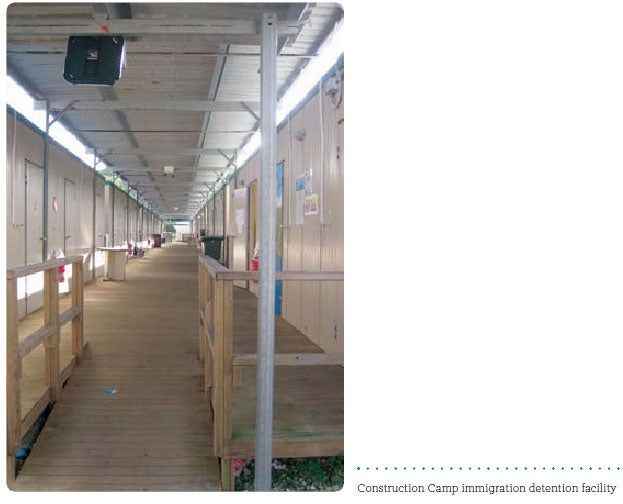

- Families with children and unaccompanied minors are detained in an immigration detention facility on Christmas Island (the Construction Camp), rather than being placed in Community Detention. The Construction Camp is not an appropriate environment for children, and has become increasingly overcrowded.

- There continues to be a lack of clarity about responsibilities for child welfare and protection for children in immigration detention on Christmas Island.

- There remains a conflict of interest in the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (the Minister) or DIAC officers acting as the legal guardian of unaccompanied minors detained on Christmas Island.

Conditions and services in detention

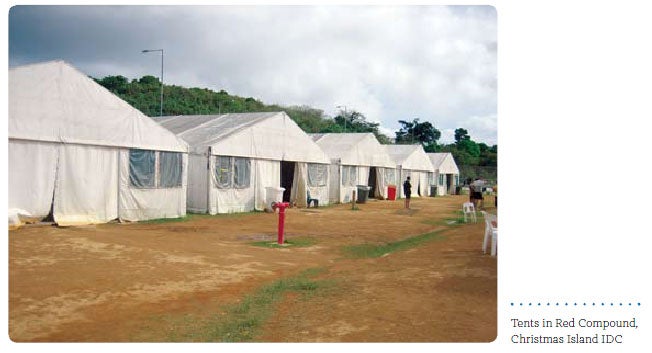

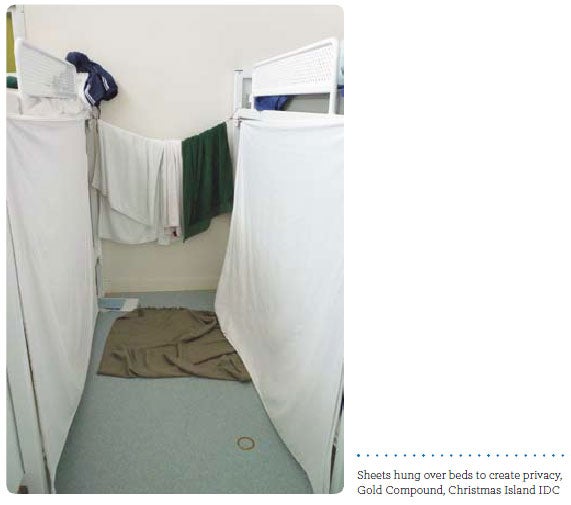

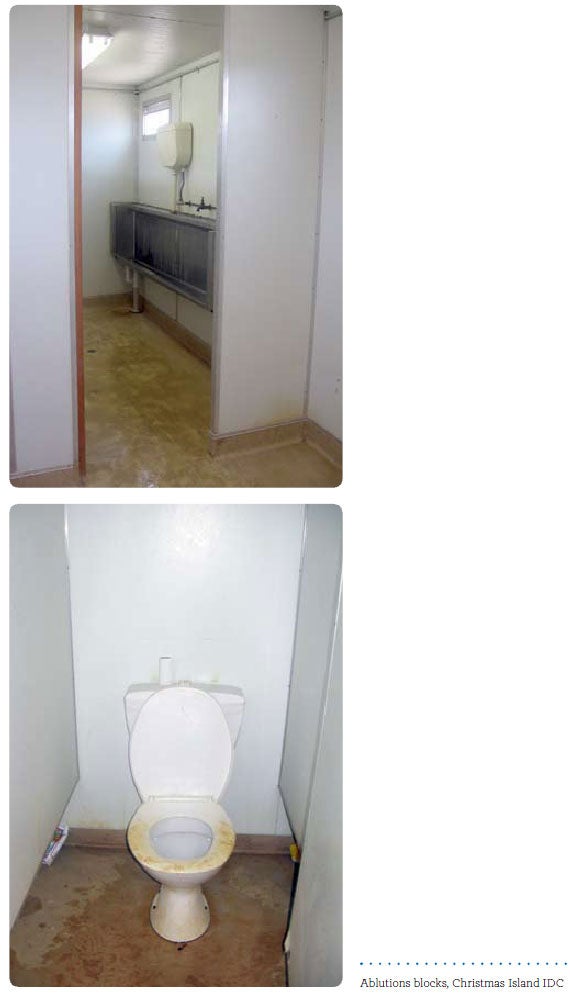

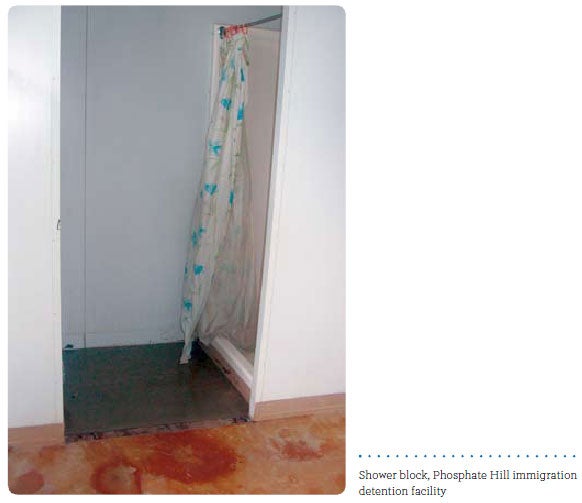

- The detention facilities on Christmas Island are not appropriate for asylum seekers. The Commission has ongoing concerns about the prison-like nature of the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre (IDC), the limited amenities at the Phosphate Hill facility, and the inappropriateness of the Construction Camp as a place for accommodating families with children and unaccompanied minors.

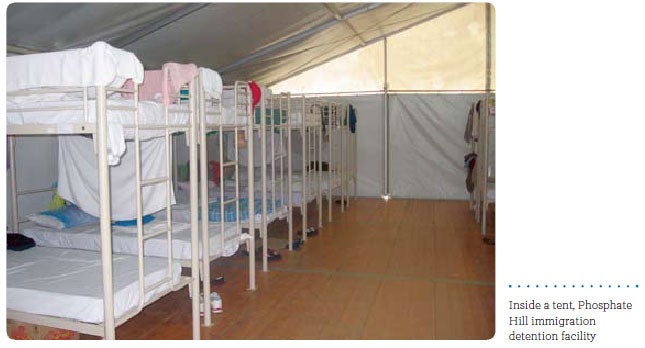

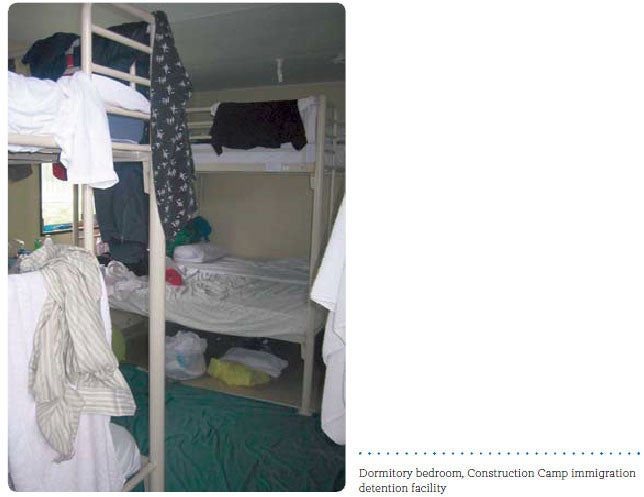

- The substantial increase in the number of people in detention has led to overcrowding in the detention facilities on Christmas Island. There has been a significant deterioration in living conditions for many people, particularly those accommodated in tents and dormitory bedrooms.

- The substantial increase in the number of people in detention has placed further strain on their access to facilities and services including communication facilities, recreational facilities, educational activities and opportunities for people to leave the detention environment.

Access to health and mental health care

- People in immigration detention on Christmas Island have limited access to medical specialists and dental care.

- There is no psychiatrist on Christmas Island. Mental health staff are being required to provide services to a high number of people in detention. There have been a number of self-harm incidents in recent months.

- There is a need for rigorous, independent monitoring of the delivery of health and mental health services for people in immigration detention.

While there have been some improvements since its last visit, the Commission remains of the view that Christmas Island is not an appropriate place in which to hold people in immigration detention. The Commission’s long-held concerns about detaining asylum seekers in a place as small and remote as Christmas Island have been compounded this year by the overcrowding and deterioration in conditions. The Commission opposes the mandatory detention of asylum seekers. However, if people must be detained, they should be accommodated on the Australian mainland in metropolitan locations where they can access the services and support they need.

The Commission also remains of the view that the excision regime should be repealed. It establishes a two-tiered system under which asylum seekers are treated differently based on their place and mode of arrival. Asylum seekers arriving in excised offshore places are assessed through a non-statutory system that affords them fewer legal safeguards than asylum seekers arriving on the mainland. In the Commission’s view, all asylum seekers who arrive in Australia should be permitted to apply for protection through the refugee status determination system that applies under the Migration Act.

Regardless of how or where they arrive in Australia, all people are entitled to protection of their fundamental human rights. These include the right to seek asylum, the right not to be subjected to arbitrary detention, and the right to be treated with humanity and respect if they are deprived of their liberty.[11] The Commission continues to encourage the Australian Government to ensure that the treatment of all asylum seekers arriving in Australia is in line with these and other human rights obligations.

4 Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Australian Government should stop using Christmas Island as a place in which to hold people in immigration detention. If people must be held in immigration detention facilities, they should be located in metropolitan areas.

Recommendation 2: The Australian Government should repeal the provisions of the Migration Act relating to excised offshore places and abandon the policy of processing some asylum claims through a non-statutory refugee status assessment process. All unauthorised arrivals who make claims for asylum should have those claims assessed through the refugee status determination system that applies under the Migration Act.

Recommendation 3: If the Australian Government intends to continue to use Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, it should avoid the prolonged detention of asylum seekers by:

- Ensuring full implementation of the New Directions policy under which asylum seekers should only be held in closed detention facilities while their health, identity and security checks are conducted. After this, the presumption is that they will be permitted to reside in the community unless a specific risk justifies their ongoing detention in a facility.

- Ensuring that security clearances are conducted as quickly as possible.

Recommendation 4: Section 494AA of the Migration Act, which bars certain legal proceedings in relation to offshore entry persons, should be repealed. The Migration Act should be amended to accord with international law by requiring that a decision to detain a person, or a decision to continue a person’s detention, is subject to prompt review by a court.[12]

Recommendation 5: The Australian Government should make full use of the Community Detention system for people detained on Christmas Island. All eligible detainees should be referred for a Residence Determination on the mainland. This should be an immediate priority for vulnerable groups including families with children, unaccompanied minors, survivors of torture or trauma, and people with health or mental health concerns.

Recommendation 6: The Australian Government should implement the outstanding recommendations of the report of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, A last resort?.[13] These include that Australia’s immigration detention laws should be amended, as a matter of urgency, to comply with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In particular, the new laws should incorporate the following minimum features:

- There should be a presumption against the detention of children for immigration purposes.

- A court or independent tribunal should assess whether there is a need to detain children for immigration purposes within 72 hours of any initial detention (for example, for the purposes of health, identity or security checks).

- There should be prompt and periodic review by a court of the legality of continuing detention of children for immigration purposes.

- All courts and independent tribunals should be guided by the following principles:

- detention of children must be a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time

- the best interests of children must be a primary consideration

- the preservation of family unity

- special protection and assistance for unaccompanied children.

Recommendation 7: If the Australian Government intends to continue the practice of holding children in immigration detention on Christmas Island it should, as a matter of priority:

- clarify through formal Memoranda of Understanding the respective roles and responsibilities of state and federal authorities with regard to the welfare and protection of children in immigration detention on Christmas Island

- clearly communicate these roles and responsibilities to all relevant state and federal authorities

- finalise and implement clear policies and procedures regarding child welfare and protection concerns that may arise in respect of children in immigration detention on Christmas Island, and communicate these policies and procedures to all relevant staff.

Recommendation 8: The Australian Government should, as a matter of priority, implement the recommendations made by the Commission in A last resort? that:

- Australia’s laws should be amended so that the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship is no longer the legal guardian of unaccompanied children.

- An independent guardian should be appointed for unaccompanied children and they should receive appropriate support.

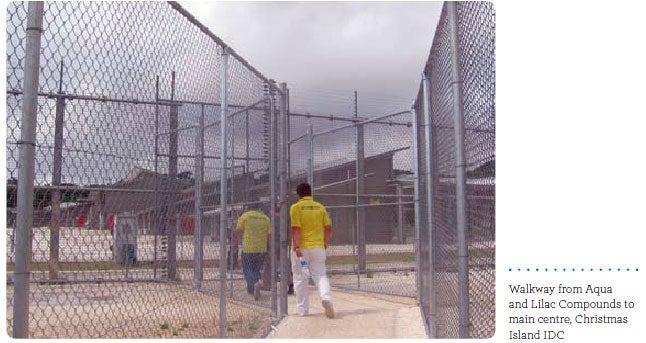

Recommendation 9: If the Australian Government intends to continue to use the Christmas Island IDC, it should implement the recommendation of the Joint Standing Committee on Migration that all caged walkways, perspex barriers, and electrified fencing should be removed and replaced with more appropriate security infrastructure.[14]

Recommendation 10: If the Australian Government intends to continue to use the Christmas Island IDC, it should take immediate measures to reduce overcrowding. These should include:

- ceasing the practice of accommodating people in tents, and removing the tents as soon as possible

- ceasing use of the surge areas that have been created by converting the visitors’ and induction areas into large dormitories

- ceasing the practice of accommodating people in dormitory bedrooms in Education 3 Compound, and returning the compound to its original use as space for educational and recreational activities

- refraining from transforming additional areas into accommodation.

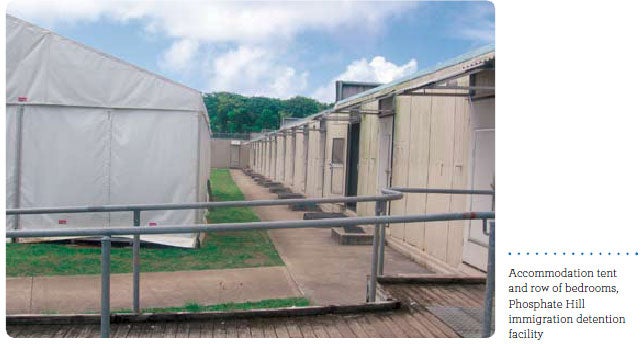

Recommendation 11: If the Australian Government intends to continue to use the Phosphate Hill immigration detention facility, it should take immediate measures to reduce overcrowding in the facility. These should include:

- ceasing the practice of accommodating people in tents, and removing the tents as soon as possible

- ceasing the practice of accommodating any more than two people in the bedrooms in the demountables.

Recommendation 12: If the Australian Government intends to continue to use the Construction Camp immigration detention facility, it should take immediate measures to reduce overcrowding in the facility.

Recommendation 13: DIAC, Serco and other detention service providers should refer to people in immigration detention by their name. Their identification number should only be used as a secondary identifier where this is necessary for clarification purposes.

Recommendation 14: DIAC and Serco should ensure that staff training and performance management include a strong focus on treating all people in immigration detention with humanity and with respect for their inherent dignity.

Recommendation 15: An independent body should be charged with the function of monitoring the provision of health and mental health services in immigration detention. The Australian Government should ensure that adequate resources are allocated to that body to fulfil this function.

Recommendation 16: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should ensure that detainees are provided with access to appropriate health services. In particular, DIAC should ensure, as a matter of priority, that detainees on Christmas Island are provided with adequate access to dental care and specialist care.

Recommendation 17: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should ensure that detainees are provided with access to appropriate mental health services. In particular, DIAC should ensure, as a matter of priority, that detainees on Christmas Island are provided with adequate access to psychiatric care.

Recommendation 18: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should ensure that detainees are provided with adequate access to torture and trauma services.

Recommendation 19: DIAC should ensure that its policy, Identification and Support of People in Immigration Detention who are Survivors of Torture and Trauma is implemented on Christmas Island. Under this policy, the continued detention of survivors of torture and trauma in an IDC is only to occur as a measure of absolute last resort where risk to the Australian community is considered unacceptable.

Recommendation 20: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should:

- ensure that all detainees are provided with adequate access to telephones and that they can make and receive telephone calls in privacy

- increase the number of internet terminals in each of the detention facilities.

Recommendation 21: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should ensure that all detainees are provided with adequate access to a range of recreational facilities and activities.

Recommendation 22: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should ensure that:

- all detainees have access to appropriate educational activities, including ESL classes

- the Phosphate Hill and Construction Camp immigration detention facilities have an adequate supply of reading materials in the principal languages spoken by detainees.

Recommendation 23: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should:

- amend the detention service provider contract applicable to the three detention facilities on Christmas Island to require that Serco provide regular external excursions for people in detention on the island

- ensure that the detention service provider is allocated sufficient resources to provide escorts for regular external excursions.

Recommendation 24: If the Australian Government intends to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, DIAC should:

- ensure that all detainees are provided with access to regular religious services conducted by qualified religious representatives – in particular, further efforts are required to provide this for detainees who practice a religion other than Christianity

- ensure that detainees have access to religious services in the community.

Recommendation 25: Legislation should be enacted to set out minimum standards for conditions and treatment of detainees in all of Australia’s immigration detention facilities, including those located in excised offshore places. The minimum standards should be based on relevant international human rights standards, should be enforceable and should make provision for effective remedies.

Recommendation 26: The Australian Government should ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and establish an independent and adequately resourced National Preventive Mechanism to conduct regular inspections of all places of detention. This should include all immigration detention facilities, including those located in excised offshore places.

5 Overview: immigration detention on Christmas Island

5.1 Who is detained on Christmas Island?

The current policy of the Australian Government is that all non-citizens who arrive by boat without a valid visa (irregular maritime arrivals) are taken to Christmas Island and placed in immigration detention.[15] This includes people who arrive by boat in excised offshore places, and people who arrive by boat on the Australian mainland.[16]

The vast majority of these arrivals are asylum seekers. A small number are crew members.

At the time of the Commission’s visit, the vast majority of people detained on Christmas Island were from Afghanistan or Sri Lanka. Other major nationalities included Iranian, Iraqi and Burmese. There were also a significant number of stateless people in detention.[17]

5.2 How many people are detained on Christmas Island?

The number of people in immigration detention on Christmas Island has increased significantly since the Commission’s July 2009 visit. At that time, there were 733 people in immigration detention on the island.[18]

At the start of the Commission’s 2010 visit, there were 2421 people in immigration detention on Christmas Island, including 250 minors.[19] At the same time, there were 1045 irregular maritime arrivals in detention on the mainland, including 246 minors.[20]

At the time of writing, there were 2409 people detained on Christmas Island, including 217 minors. There were also 1950 irregular maritime arrivals in detention on the mainland, including 439 minors.[21]

At the time of writing, the highest number detained on Christmas Island at any one time was 2652 people in late July 2010.[22]

5.3 How long are people detained on Christmas Island?

The majority of the 2421 people detained on Christmas Island at the time of the Commission’s visit had been there for less than three months.[23] However, 656 people had been detained for three months or more. Of those 656 people, 305 had been detained for six months or more; and of those 305 people, 121 had been detained for nine months or more.[24]

The Commission is concerned that more people are being held in detention on Christmas Island for longer periods of time, as discussed in section 9 of this report.

5.4 Where are people detained?

There are three immigration detention facilities on Christmas Island:

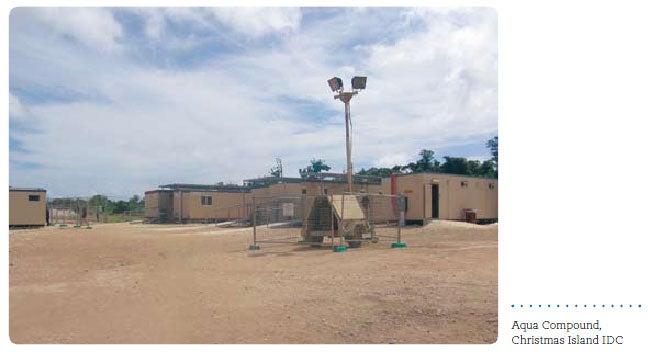

- The Christmas Island IDC – a high security detention centre used for adult males. When the Commission visited, there were 1834 men detained in the IDC.[25]

- The Construction Camp immigration detention facility – a low security detention facility used primarily for unaccompanied minors and families with children. When the Commission visited, there were 418 people detained in the Construction Camp – 73 men, 75 women, 94 accompanied children, 152 unaccompanied minors and 24 male crew members.[26]

- The Phosphate Hill immigration detention facility – a secure detention facility used for adult males. When the Commission visited, there were 164 men detained in the facility.[27]

At the time of the Commission’s visit, the detention facilities were being operated by Serco Australia, the detention service provider contracted by the Australian Government.

Some immigration detainees on Christmas Island were formerly placed in Community Detention and accommodated in houses in the local community.[28] During the Commission’s 2010 visit, there were only three people in Community Detention.[29] Since then, the use of Community Detention on Christmas Island has ceased due to a lack of available accommodation. The Commission is concerned about this development, as discussed in section 11 of this report.

PART B: Key policy and processing developments

Since the Commission’s 2009 visit to Christmas Island, there has been a range of significant developments. This part of the report considers some of the key policy and processing developments that have impacted on conditions for people in detention on Christmas Island over the past year.

6 Increasing detainee numbers and transfers to mainland detention facilities

Over the past year there has been an increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat and a substantial increase in the number of people being held in immigration detention on Christmas Island. There were 733 people in detention on Christmas Island when the Commission visited in July 2009. By the time of the Commission’s 2010 visit this had increased to 2421 people.[30]

The increase in arrivals has contributed to slower processing of asylum applications and longer periods of detention, as discussed in the following sections of this report. It has also placed increasing pressures on DIAC and Serco staff, as they have been required to meet the needs of an ever-increasing number of people in detention. A rise in the number of DIAC officers on Christmas Island and an enhanced Case Management system appear to have assisted in meeting these challenges. The Commission acknowledges that many staff are making significant efforts to ensure that people in detention are treated appropriately despite the difficult circumstances.

However, the detention facilities on Christmas Island were not designed to accommodate such a high number of people.[31] The substantial increase in detainee numbers has led to overcrowding, a significant deterioration in living conditions, increased pressure on services such as health and mental health care, and restrictions on access to facilities such as telephones, washing machines, ablutions and recreational facilities. These issues are discussed further in Part D of this report.

The increasing pressure on the island’s detention facilities eventually led to decisions by the Australian Government during the first half of 2010 to transfer some people to existing immigration detention facilities on the mainland, to re-open the Curtin IDC and the Port Augusta Immigration Residential Housing, and to establish a range of other ‘alternative places of detention’ on the mainland.[32]

The Commission has long recommended that the Australian Government stop using Christmas Island as a place for holding people in immigration detention.[33] The overcrowding and the deteriorating conditions in the island’s detention facilities add weight to that recommendation. The Commission therefore welcomes the transfer of some detainees from Christmas Island to the mainland. It is essential that these transfers continue in order to relieve the ongoing pressures on detainees, staff, facilities and services on Christmas Island. Transfers should be a matter of priority for all families with children, unaccompanied minors, survivors of torture or trauma, and people with health or mental health concerns.

However, the Commission regrets that the vast majority of people transferred to the mainland to date have been placed in immigration detention facilities, rather than being considered for a bridging visa or a Community Detention placement. The Commission has also expressed concern about the decision to detain people in remote locations such as Curtin, where their access to appropriate services and support networks is limited and the accessibility and transparency of their detention arrangements is reduced.[34] In the Commission’s view, many of the factors that make Christmas Island an inappropriate place in which to detain people also make remote locations like Curtin inappropriate. If people must be held in immigration detention facilities, they should be located in metropolitan areas.

7 Excision and offshore processing

7.1 The excision regime and the non-statutory RSA process

Under Australia’s excision regime, various islands are designated as ‘excised offshore places’, and a person who becomes an unlawful non-citizen (a non-citizen without a valid visa) by entering Australia at one of these places is referred to as an ‘offshore entry person’.[35] An offshore entry person is barred from submitting a visa application unless the Minister determines that it is in the public interest to allow them to do so.[36] Refugee claims made by offshore entry persons are instead assessed through a non-statutory refugee status assessment process (the RSA process).

The Commission’s 2009 report outlined the excision regime and the RSA process in further detail.[37] The Commission expressed concerns about excision and the policy of assessing the claims of asylum seekers who arrive in excised offshore places through a non-statutory process.[38]

DIAC’s response to the Commission’s report highlighted improvements that had been made to the RSA process under the government’s New Directions in Detention reforms.[39] These improvements included access for asylum seekers to publicly funded migration advice and assistance through the Immigration, Advice and Application Assistance Scheme (IAAAS), independent review of unfavourable RSA decisions, and an external scrutiny role for the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

The Commission has welcomed these improvements.[40] The Commission acknowledges that substantial reforms have been made in recent years which have improved the processing of refugee claims made by offshore entry persons. However, improvements in the operation of the process do not overcome the Commission’s fundamental concerns about the system itself.

The Commission remains opposed to the excision regime because it establishes a two-tiered system under which asylum seekers are treated differently based on their place and mode of arrival. Asylum seekers arriving in excised offshore places are barred from the refugee status determination system that applies under the Migration Act, and instead are assessed through a non-statutory system that affords them fewer legal safeguards than asylum seekers arriving on the mainland. In the Commission’s view, this differential treatment undermines Australia’s obligations under the Refugee Convention and undermines asylum seekers’ human rights.[41]

The key recommendations of the Commission’s 2009 report included that the provisions of the Migration Act relating to excised offshore places be repealed, the policy of processing some asylum claims through a non-statutory process be abandoned, and all unauthorised arrivals who make claims for asylum have those claims assessed through the system that applies under the Migration Act.[42] The Commission reiterates those recommendations.

The Commission is aware that several legal challenges relating to the RSA process are under consideration by the High Court of Australia. The Commission will monitor developments in this area.

7.2 RSA processing times

At the time of the Commission’s 2009 visit to Christmas Island, it was taking an average of 66 days from the time an asylum seeker lodged their statement of claims under the RSA process until they were notified of their RSA outcome.[43] The Commission welcomed the fact that the majority of asylum seekers on Christmas Island were moving through the RSA process relatively quickly, but expressed concern that this was vulnerable to change because there are no binding timeframes under the process.[44]

Since then, the increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat has contributed to slower RSA processing. As of July 2010, on average it was taking 41 days from a person’s arrival on Christmas Island until lodgement of their statement of claims, and a further 72 days from that lodgement until their protection visa grant. This means that those asylum seekers receiving a successful RSA outcome were spending an average of 113 days (more than 16 weeks) in detention before their protection visa grant.[45]

However, these average processing figures fail to convey the current reality that many asylum seekers are spending much longer periods in detention on Christmas Island awaiting the outcome of the RSA process or the conduct of security checks (as discussed in section 9 below).

Over the coming year, higher refusal rates are likely to lead to further increases in average RSA processing times, as more asylum seekers will go through independent merits review after receiving a negative primary decision. As of July 2010, it was taking an average of 75 days from the lodgement of a request for independent merits review until the review outcome.[46] This is in addition to the time taken from arrival on Christmas Island to receiving a negative primary decision.

The Commission acknowledges the pressures on DIAC decision-makers caused by the increased number of RSA claims lodged over the past year, and the efforts being made by DIAC officers to keep processing times as short as possible. The Commission’s major concern with slower processing times is that they can lead to people being held in immigration detention for longer periods, and that the prolonged detention of asylum seekers can have serious detrimental impacts on their mental health – particularly when their detention is combined with the uncertainty of not knowing what the outcome of their refugee claim will be.

7.3 Independent merits review

In its 2009 report, the Commission welcomed the introduction of access to independent merits review for asylum seekers who receive a negative primary decision through the RSA process. However, the Commission expressed concerns that this did not constitute a sufficient legal safeguard for those asylum seekers, primarily due to the lack of transparent and enforceable procedures for decision-making.[47]

Unlike an asylum seeker who arrives on the mainland, one who arrives in an excised offshore place does not have access to independent merits review by the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) or the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT).[48] Instead they have access to an Independent Reviewer who will consider their refugee claim and make a non-binding recommendation to the Minister as to whether the Minister should exercise his or her discretion to permit the person to apply for a protection visa.[49]

As of July 2010, there were 432 people going through independent merits review under the RSA process. This included 245 people waiting for a review hearing to be scheduled, 150 people with a hearing currently taking place or scheduled to take place within the next month, and 37 people whose hearings had been completed and who were awaiting the review outcome.[50]

The higher number of RSA claims being lodged and increasing refusal rates at the primary stage have led to a need for the independent merits review system to be expanded. The Commission has been informed that, in order to meet increased demands, additional Independent Reviewers have been appointed and a new office has been established to provide administrative support. This is known as the Refugee Status Review Office. It will operate and be physically separate from DIAC, but the CEO will report to the DIAC Secretary on the operations of the Office.

The Commission supports the fact that additional reviewers have been appointed to assist in meeting increased demands. However, the Commission remains concerned about the limited transparency surrounding the independent merits review system. As discussed, the Commission would prefer to see the excision regime repealed and the non-statutory RSA process abandoned. However, if the Australian Government intends to retain the RSA process, the Commission recommends that steps be taken to increase transparency surrounding the independent merits review system.

This could include measures such as ensuring that recruitment and appointment processes for Independent Reviewers are fully transparent; making the RSA manual and the independent merits review guidelines publicly available; publishing de-identified independent merits review decisions; and regularly publishing statistics on the number of primary decisions affirmed and overturned by Independent Reviewers.

While DIAC might provide much of this information to the Commission and other oversight bodies on request, in the Commission’s view it is important that it be accessible to the general public.

8 Suspension of processing

One of the most concerning developments over the past year occurred on 9 April 2010, when the Australian Government announced that it was suspending the processing of claims lodged by asylum seekers arriving on or after that date from Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, for three and six months respectively.[51]

The Commission expressed serious concerns about this decision when it was announced.[52] In the Commission’s view, the suspension policy undermined Australia’s international human rights obligations, including obligations under the CRC, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

The Commission welcomed the lifting of the Sri Lankan suspension on 6 July 2010.[53] When it was lifted, there were 184 Sri Lankans who had arrived by boat subject to the suspension, including 19 accompanied children and two unaccompanied minors. These people were held in immigration detention in the Construction Camp facility on Christmas Island and in facilities in Leonora and Darwin.[54]

The Commission encouraged the Australian Government to lift the remaining suspension on Afghan asylum seekers as a matter of urgency.[55] That suspension remained in place until it was lifted on 30 September 2010. At that time, there were 1210 Afghans who had arrived by boat subject to the suspension, including 25 accompanied children and 208 unaccompanied minors. These people were in various immigration detention facilities on Christmas Island and the mainland.[56]

The Commission’s greatest concern about the suspension policy was that it resulted in the prolonged detention of a significant number of people, including children. All Afghan and Sri Lankan asylum seekers who arrived by boat and who were subject to the suspension were detained for its duration. For Afghans who arrived in April 2010, this means they spent six months in detention before processing of their claims even began. Once the suspension was lifted, this would be followed by another three to six months or more in detention awaiting their primary RSA decision, and in some cases the outcome of independent merits review.

Many of those who were subject to the suspension are children, including unaccompanied minors. Under the CRC they should only be detained as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.[57] The suspension policy was inconsistent with this obligation. In addition, the prolonged or indefinite detention of asylum seekers subject to the suspension may have led to breaches of Australia’s obligations under the ICCPR not to subject anyone to arbitrary detention.[58]

The Commission is particularly concerned that the prolonged detention of asylum seekers who were subject to the suspension may have significant impacts on their mental health, especially in the case of unaccompanied minors, families with children, and survivors of torture or trauma. The Commission’s National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention found a clear link between uncertainty experienced by asylum seekers in detention and deterioration of their mental health.[59] It also found that children in detention for long periods of time are at high risk of serious mental harm.[60]

When the Commission visited Christmas Island in 2010, there were almost 700 people in detention subject to the suspension. One group of Afghan men spoke about the psychological impacts of the suspension, saying that most of them could not sleep. They felt it was unfair that they could be detained for a long time, given they had committed no crime.[61] A group of Afghan women at the Construction Camp raised concerns about the impact on their children of being detained throughout the suspension period.[62]

The impacts of the suspension policy were also evident in terms of the increased number of people being held in the detention facilities on the island, contributing to overcrowding and a deterioration in conditions (as discussed in section 17 below).

The Commission has encouraged the Department of Immigration and Citizenship to move quickly to process the backlog of asylum claims caused by the suspension.[63]

9 Length of detention

Under the government’s New Directions policy, detention is to be used for the shortest practicable period.[64] The Commission welcomed this commitment, and encouraged the government to embed it in legislation. Last year, the Commission welcomed the introduction of the Migration Amendment (Immigration Detention Reform) Bill 2009. While the Commission raised some concerns about the Bill and suggested amendments, it is disappointed that the Bill was not enacted as it would have gone some way towards implementing this aspect of the New Directions policy.[65] As the Migration Act stands, there is no time limit on the period a person may be detained.[66]

The Commission is concerned that more people are being held in detention on Christmas Island for longer periods of time. When the Commission visited Christmas Island in July 2009, there were 114 people who had been detained for three months or more, 15 of whom had been detained for six months or more.[67] During its 2010 visit, this had increased to 656 people who had been detained for three months or more, 305 of whom had been detained for six months or more. Of those 305 people, 121 had been detained for nine months or more.[68]

Importantly, while some people spend their whole period of detention on Christmas Island, others spend an initial period there before being transferred to a detention facility on the mainland. For these people, the time they are detained on Christmas Island does not reflect their total period in detention.

The causes of longer periods of detention include the increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat; slower processing of asylum applications; increasing refusal rates at the primary stage leading to more asylum seekers going through independent merits review; and the fact that a significant number of Afghan and Sri Lankan asylum seekers were subject to the processing suspension.

A further factor having a significant impact on people’s length of detention is delays in obtaining security clearances. Under the New Directions policy, an asylum seeker should only be held in a closed detention facility for as long as it takes to conduct their health, identity and security checks. After this, the presumption is that they will be permitted to reside in the community unless a specific risk justifies their ongoing detention in a facility.[69]

Last year the Commission raised doubts as to whether detainees on Christmas Island were being released into the community once their checks had been completed, and expressed the view that the shortage of community-based accommodation on the island was likely to be a key factor in preventing this from happening.[70] This year, the use of Community Detention on Christmas Island has ceased, due to the lack of accommodation. This means that if any asylum seekers have their health, identity and security checks completed in advance of their RSA outcome, there is nowhere on Christmas Island outside of the detention facilities to move them to.

However, it appears that there are few people whose security clearances are completed in advance of their RSA outcome, undermining this aspect of the New Directions policy. Some asylum seekers are being detained for prolonged periods while they await their security clearances. Some of these people may have gone through the RSA process and been recognised as a refugee, but they will not be granted a protection visa until they receive their security clearance.

During its visit to Christmas Island, the Commission spoke with a significant number of Sri Lankan detainees who had gone through the RSA process and were awaiting security clearances. Some of them had been detained for almost one year. They expressed considerable frustrations about their situation, in particular the lack of information provided about progress with their individual cases, the reasons for delay with the security clearances, and the potential timeframes they would have to remain in detention.[71] One group said they could not bear the waiting and the uncertainty – according to one man, “We should have died in Sri Lanka or in the ocean.”[72]

The Commission acknowledges that DIAC is not responsible for the delays in the conduct of security clearances; these checks are carried out by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). The increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving by boat has led to an increase in the number of security clearances to be conducted by ASIO, contributing to the delays.

The Commission also acknowledges that the time periods asylum seekers are currently spending in detention are not as long as the periods for which some people were detained in the past. However, there are currently significant numbers of people who have been detained for around one year, and the situation has the potential to deteriorate further.

The Commission emphasises the need for the Australian Government to take all appropriate steps to ensure that asylum seekers are not detained for prolonged periods. This should include taking all practicable steps to ensure that security clearances are conducted as quickly as possible. It should also include full implementation of the New Directions policy that asylum seekers will only be held in detention while their health, identity and security checks are conducted. In the Commission’s view, after this they should be granted bridging visas to reside in the community on the mainland while their claims are processed.[73]

- Ensuring full implementation of the New Directions policy under which asylum seekers should only be held in closed detention facilities while their health, identity and security checks are conducted. After this, the presumption is that they will be permitted to reside in the community unless a specific risk justifies their ongoing detention in a facility.

- Ensuring that security clearances are conducted as quickly as possible.

10 Potential for indefinite or arbitrary detention

The Commission has consistently called for the repeal of Australia’s mandatory detention system because it leads to breaches of Australia’s obligations to ensure that no one is arbitrarily detained.[74] The government’s policy of mandatory detention of all irregular maritime arrivals on Christmas Island is particularly concerning given that the Migration Act does not require detention in excised offshore places – legally, it is a matter of discretion.[75]

In its 2009 report, the Commission recommended that, if the Australian Government intended to continue using Christmas Island for immigration detention purposes, it should abolish the policy of mandatorily detaining all irregular maritime arrivals.[76] The mandatory detention policy is based on a blanket approach, rather than an assessment of the need to detain in each person’s case. This is inconsistent with United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) guidelines, under which there should be a presumption against the detention of asylum seekers – it should be the exception rather than the norm. Detention should only be resorted to if there is evidence to suggest that other alternatives will not be effective in the individual case.[77]

The Commission welcomed the inclusion of a key value in the New Directions policy acknowledging that indefinite or otherwise arbitrary detention is not acceptable, and committing to regular review of the length and conditions of detention.[78] However, the Commission expressed concern in its 2009 report that insufficient reforms had been implemented to ensure that this value is realised in practice.[79] These concerns were reinforced during the Commission’s 2010 visit.

As discussed in section 8 above, the Commission is concerned that the prolonged or indefinite detention of asylum seekers who were subject to the suspension may have led to breaches of Australia’s obligations under the ICCPR not to subject anyone to arbitrary detention.[80] The mandatory detention of children for a prolonged or indefinite period of time under the suspension policy was also inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under the CRC to avoid the arbitrary detention of children, and to only detain them as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.[81]

The Commission was also concerned during its recent visit about the situation of seven individuals who are facing an indefinite period in immigration detention as a result of receiving adverse security assessments from ASIO.[82] At the time, three of these individuals had been detained on Christmas Island for five months. The other four were parents with two young children – the mother and children had been detained for five months, and the father for eleven months. The Commission urges the Australian Government to ensure that durable solutions are provided for these individuals, and they are removed from immigration detention as soon as possible.

In addition, the Commission has concerns about the review mechanisms designed to ensure that indefinite or otherwise arbitrary detention does not occur. The New Directions introduced two new mechanisms: a three-monthly review by a senior DIAC officer to certify that the further detention of the individual is justified; and a six-monthly review by the Commonwealth Ombudsman to consider the appropriateness of the person's ongoing detention and their detention arrangements.[83] The Commission welcomed these reforms in its 2009 report. However, the Commission expressed concerns that these review processes would not be sufficient to ensure that arbitrary detention did not occur, in particular because the DIAC reviews are not conducted by an independent body, and the Ombudsman is not able to enforce his assessments.[84]

In the intervening period, community representatives have raised concerns with the Commission about the lack of transparency surrounding these review processes. The Commission has also been informed by DIAC that there are currently significant delays in undertaking these review processes for people detained on Christmas Island. The Commission is concerned that this may lead to some people being held in detention on Christmas Island for more than six months before an independent body considers the appropriateness of their detention arrangements.

The Commission encourages the Australian Government to ensure that adequate resources are allocated to allow for the three and six month review processes to be conducted on time for each person detained on Christmas Island. The reviews should include consideration of any appropriate alternatives to the individual’s ongoing detention in a facility on Christmas Island.

The Commission also encourages the Australian Government to increase transparency surrounding these detention reviews. This could be done by implementing the recommendations made by the Joint Standing Committee on Migration, including that DIAC should publish details of the three month review process and provide the review to the individual in detention; and that the Ombudsman’s six month reports should be tabled in Parliament and the Minister required to respond.[85]

Finally, the Commission reiterates its long-held view that the essential safeguard required to ensure that arbitrary detention does not occur is access to review by a court of any decision to detain, or to continue a person’s detention. Currently, in breach of its international obligations, Australia does not provide this.[86] Further, the Migration Act purports to bar offshore entry persons from taking legal proceedings relating to the lawfulness of their detention.[87]

In response to the Commission’s 2009 report, DIAC stated that the matter of judicial review was being considered in the context of the government’s response to the recommendations made by the Joint Standing Committee on Migration in its Inquiry into Immigration Detention in Australia.[88] This response has not yet been released.

11 Under-utilisation of the Community Detention system

When the Commission visited Christmas Island in July 2009, there were 44 people in Community Detention on the island. The Commission raised concerns that the shortage of community-based accommodation appeared to be preventing the release of some detainees from detention facilities into Community Detention. At the time, DIAC had capacity to place up to 60 people in Community Detention on the island, and steps were being taken to increase that capacity. However, given the small size of the community and the number of people in detention, the Commission raised doubts about the feasibility of securing an adequate level of community-based accommodation.[90]

During its 2010 visit, there were only three people in Community Detention on Christmas Island.[91] Shortly after the Commission’s visit, the use of Community Detention ceased because of a lack of available accommodation. The Commission has significant concerns about this development. The Commission acknowledges that DIAC is working within considerable constraints in terms of the accommodation available on Christmas Island, and that there are significant needs for staff accommodation. However, in the Commission’s view, the fact that there is not enough accommodation to allow for use of Community Detention on Christmas Island reinforces the conclusion that the island is not an appropriate place to detain people.

The Commission also has significant concerns that the Community Detention system is barely being used on the mainland. While the Commission has welcomed the transfer of some detainees from Christmas Island to the mainland, the Commission regrets that the vast majority of these people have been transferred to immigration detention facilities rather than placed in Community Detention. At the time of writing, there were 1950 irregular maritime arrivals in detention on the mainland, including 439 minors. Only seven of these people were in Community Detention.[92]

The Community Detention system was established to ensure that people, particularly vulnerable groups, would not be held in immigration detention facilities for prolonged periods. Under the Residence Determination Guidelines, priority for Community Detention is to be given to children and accompanying family members; persons who may have experienced torture or trauma; persons with significant physical or mental health problems; cases which will take a considerable period to substantively resolve; and other cases with unique or exceptional characteristics. Priority cases are to be assessed and referred to the Minister ‘as soon as practicable’.[93] Other cases may be referred where DIAC considers it appropriate to do so.[94]

The Commission is concerned that these Guidelines are not being implemented on Christmas Island or the mainland. Many of the people currently in immigration detention facilities would appear to fit into the groups that are intended to be prioritised for Community Detention. For example, this is the case for families with children and unaccompanied minors (as discussed in section 13 below), and survivors of torture or trauma (as discussed in section 19 below).

The Commission welcomes efforts by DIAC to ensure that some of these vulnerable groups are located in low security detention facilities or ‘alternative places of detention’, rather than high security immigration detention centres. However, it is important to note that being detained in an ‘alternative place of detention’ (also referred to as ‘alternative temporary detention in the community’), is not the same as being in Community Detention under a Residence Determination.

People in ‘alternative places of detention’ are usually in a designated detention facility, camp or motel-type accommodation. They remain under physical supervision and are not free to come and go. People in Community Detention, on the other hand, are permitted to live at a specified residence in the community – usually a house or apartment. They remain in immigration detention in a legal sense and they must meet certain conditions, which usually include reporting to DIAC on a regular basis, sleeping at their stipulated residence every night, and refraining from engaging in paid work or a formal course of study. However, they are not under physical supervision and they have a much greater degree of privacy and autonomy.

DIAC has informed the Commission that one of the reasons for the current under-utilisation of the Community Detention system is that most irregular maritime arrivals in immigration detention facilities do not yet have their security clearances. However, the Commission notes that, legally, a person in Community Detention remains in immigration detention.[95] The Community Detention system allows for the imposition of a range of conditions which can be used to mitigate particular risks that might be posed by an individual. This is specifically acknowledged in the Residence Determination Guidelines.[96]

The Commission encourages the Australian Government to make full use of the Community Detention system for people detained on Christmas Island. While the lack of accommodation on the island has limited the availability of Community Detention there, those restrictions do not apply on the mainland. All eligible detainees should be referred for a Residence Determination on the mainland.

The Commission also encourages further consideration of the proposal included in the Migration Amendment (Immigration Detention Reform) Bill 2009, which would have enabled the Minister to delegate to senior DIAC officers the Minister’s power to issue Residence Determinations.[97] In the Commission’s view, allowing the Minister to delegate this power may assist by reducing the burden on the Minister to personally consider individual cases, and by speeding up decision-making so that people are not unduly held in immigration detention facilities while awaiting a decision on a Residence Determination.

PART C: Children in detention on Christmas Island

In its 2009 report, the Commission expressed significant concerns about the detention of unaccompanied minors and families with children on Christmas Island. The Commission expressed the view that Christmas Island is not an appropriate place in which to hold people in immigration detention, especially children.[98]

During the Commission’s 2010 visit, there were 247 minors in detention on Christmas Island – 246 in the Construction Camp immigration detention facility and one in Community Detention.[99] Around half of these minors were 16 or 17 years old, but there were a significant number of younger children including 45 between the ages of zero and five years.[100]

The Commission acknowledges the efforts being made by DIAC and Serco staff, in challenging circumstances, to mitigate the impacts of immigration detention on children. However, the Commission continues to have significant concerns about the detention of families with children and unaccompanied minors on Christmas Island. The Commission’s key concerns include the following:

- Children continue to be subjected to mandatory detention on Christmas Island, despite the fact that this is not required by the Migration Act and is inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under the CRC.

- Families with children and unaccompanied minors are detained in a closed immigration detention facility – the Construction Camp. Community Detention is no longer available on Christmas Island. Further, in the vast majority of cases where families with children or unaccompanied minors are transferred to the mainland, they are placed in detention facilities rather than Community Detention.

- The Construction Camp is not an appropriate environment for families with children or unaccompanied minors. There has been a substantial increase in the number of people detained in the Construction Camp, significantly reducing the level of amenity.

- There continues to be a lack of clarity surrounding responsibilities and procedures relating to child welfare and protection for children in immigration detention on Christmas Island.

- There continues to be a conflict of interest in the Minister or a DIAC officer acting as the legal guardian of unaccompanied minors detained on Christmas Island, while also being the detaining authority and the visa decision-maker.

These concerns are outlined further below.

12 Mandatory detention of children on Christmas Island

The Commission is concerned that families with children and unaccompanied minors continue to be subjected to mandatory detention on Christmas Island. The Commission has long opposed the mandatory detention of children because it leads to fundamental breaches of their human rights.

In 2004, the Commission released A last resort?, the report of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention. During the period of the Inquiry, large numbers of children were detained for lengthy periods in Australia’s high security immigration detention centres.[101]

The Inquiry found that Australia’s immigration detention system was fundamentally inconsistent with the CRC. In particular, the system failed to ensure that:

- detention of children is a measure of last resort, for the shortest appropriate period of time and subject to effective independent review

- the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all actions concerning children

- children are treated with humanity and respect for their inherent dignity

- children seeking asylum receive appropriate assistance to enjoy, to the maximum extent possible, their right to development and their right to live in an environment which fosters the health, self-respect and dignity of children in order to ensure recovery from past torture and trauma.[102]

The Inquiry also found that children in immigration detention for long periods of time are at high risk of serious mental harm.[103]

Since the release of A last resort?, the Commission has welcomed positive changes including that children are no longer detained in high security immigration detention centres, and the average length of detention for children has decreased. However, children are still subjected to mandatory detention.

In 2005 the Migration Act was amended to insert section 4AA, affirming ‘as a principle’ that a minor should only be detained as a measure of last resort.[104] The Commission welcomed this development. However, as discussed in the Commission’s 2009 report, section 4AA is not being implemented on Christmas Island.[105] The government’s policy is that all irregular maritime arrivals, including families with children and unaccompanied minors, are mandatorily detained on Christmas Island. This is despite the fact that the Migration Act does not require the mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals in excised offshore places.[106]

In its 2009 report, the Commission observed that this mandatory detention policy is inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under the CRC to only detain a child as a measure of last resort, and recommended that the policy be abolished.[107] In order to comply with its obligations under the CRC, the government should consider any less restrictive alternatives available to a child in deciding whether that child is detained. A child should only be detained in exceptional cases.[108]

The Commission has also long been concerned that Australia’s immigration detention system breaches the CRC by failing to provide for child detainees to challenge their detention in a court or another independent authority.[109]

The Commission continues to advocate for changes to the Migration Act to ensure that children are only detained if it truly is a measure of last resort; and that if they are detained, it is for the shortest appropriate period of time and subject to independent and judicial review mechanisms.[110] In this regard, the Commission welcomed the introduction of the Migration Amendment (Immigration Detention Reform) Bill 2009. However, it expressed concerns that the Bill did not include sufficient measures to ensure those protections would be in place for children.[111]

The Commission’s concerns have increased over the past year as the number of unaccompanied minors and families with children in detention has increased substantially – at the time of writing, there were 217 minors in detention on Christmas Island and 439 minors in detention on the mainland.[112]

The Commission urges the Australian Government to address this issue as a matter of the highest priority.

- There should be a presumption against the detention of children for immigration purposes.

- A court or independent tribunal should assess whether there is a need to detain children for immigration purposes within 72 hours of any initial detention (for example, for the purposes of health, identity or security checks).

- There should be prompt and periodic review by a court of the legality of continuing detention of children for immigration purposes.

- All courts and independent tribunals should be guided by the following principles:

- detention of children must be a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time

- the best interests of children must be a primary consideration

- the preservation of family unity

- special protection and assistance for unaccompanied children.

13 Detention placement for children on Christmas Island

The Commission is concerned that unaccompanied minors and families with children are detained in a closed immigration detention facility on Christmas Island (the Construction Camp), rather than being placed in Community Detention.

13.1 Placement of children in the Construction Camp facility

As noted above, the Commission has welcomed positive changes since the release of A last resort?. In particular, the Commission welcomed the inclusion in the government’s New Directions policy of a key value stating that ‘[c]hildren, including juvenile foreign fishers and, where possible, their families, will not be detained in an immigration detention centre’.[114]

However, while children are no longer held in high security immigration detention centres, they are still detained in lower security detention facilities. On Christmas Island, they are detained in the Construction Camp immigration detention facility.

In its 2009 report, the Commission expressed the view that the Construction Camp is not an appropriate environment for children.[115] While DIAC categorises the Construction Camp as ‘alternative temporary detention in the community’, the Commission reiterates its view that this is misleading.[116] The Construction Camp is a low security facility – it is surrounded by a residential style fence and does not have alarms, CCTV surveillance or other intrusive security measures. The Commission welcomes this. However, it remains a detention facility from which detainees are not free to come and go.

In order to meet its obligations under the CRC, the government should consider any less restrictive alternatives before deciding to detain a child in a closed facility such as the Construction Camp. This should include Community Detention, as discussed below.

In response to the Commission’s 2009 report, DIAC noted efforts that were underway to introduce reforms relating to the decision of where and how to detain a child if that child was to be taken into immigration detention. In particular, these included the Migration Amendment (Immigration Detention Reform) Bill 2009 and a draft Ministerial Direction on the detention of minors.[117] The Commission welcomed these efforts and is disappointed that they have not progressed.

In particular, the Bill would have amended the Migration Act to require that if a minor is detained, the minor must not be detained in an immigration detention centre; and that if a minor is detained, the best interests of the child must be a primary consideration in deciding where that child is accommodated. While the Commission expressed concern that the Bill did not go further in embedding protections for children and recommended a range of amendments, the Commission is disappointed that even these modest reforms were not adopted.[118]

13.2 Under-utilisation of the Community Detention system

One of the most positive changes after the release of A last resort? was the introduction in 2005 of the Residence Determination power, under which the Minister can permit an immigration detainee to be placed in Community Detention.[119]

In its 2009 report, the Commission expressed concerns that some families with children and unaccompanied minors were detained in the Construction Camp facility on Christmas Island, rather than being placed in Community Detention. The Commission recommended that if the government intended to continue the practice of holding children in detention on Christmas Island, they should be placed with their family members in community-based accommodation.[120]

DIAC’s response to this recommendation stated that:

The priority is that minors and, where relevant their families, are promptly accommodated in the Christmas Island community under residential determinations once the appropriate checks, accommodation and supervision are in place.[121]

The Commission is concerned that Community Detention is no longer available on Christmas Island. During its 2010 visit, there were only three people in Community Detention; at the same time there were 418 people detained in the Construction Camp, including 94 accompanied children and 152 unaccompanied minors.[122] Shortly after the Commission’s visit, the use of Community Detention on Christmas Island ceased because of a lack of available accommodation. While the Commission acknowledges that DIAC is working within considerable constraints in terms of the accommodation available on Christmas Island, the Commission has significant concerns about this development, as discussed in section 11 above.

Further, while the Commission has welcomed the transfer of some families with children and unaccompanied minors from Christmas Island to the mainland, the Commission regrets that the vast majority have been transferred to immigration detention facilities rather than being placed in Community Detention.[123]

As noted in section 11, the Community Detention system was established in order to ensure that people, particularly vulnerable groups, would not be held in immigration detention facilities for prolonged periods. Under the Residence Determination Guidelines, priority is to be given to groups including children and their accompanying family members, and all minors are to be identified for a Residence Determination ‘as soon as they are detained’.[124] The Commission is concerned that these guidelines are not being implemented on Christmas Island or the mainland.

If children are to be detained, they should be placed in Community Detention with their family members or with a suitable carer if they are unaccompanied. While the lack of accommodation on Christmas Island has limited the availability of Community Detention there, those restrictions do not apply on the mainland.

The Commission urges the Australian Government to implement the recommendation in section 11 of this report to make full use of the Community Detention system for people detained on Christmas Island. All eligible detainees should be referred for a Residence Determination on the mainland. This should be an immediate priority for vulnerable groups including families with children and unaccompanied minors.

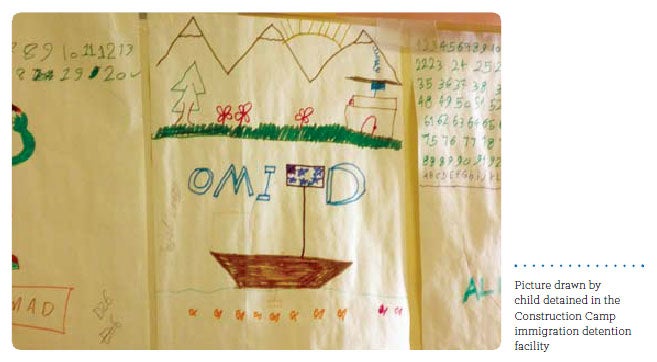

14 Conditions and services for children in the Construction Camp

As noted above, the Commission has previously stated that the Construction Camp immigration detention facility is not an appropriate environment for children. The Commission remains of this view after its 2010 visit.

The Commission acknowledges that DIAC is working within considerable infrastructure constraints, and that significant efforts are being made by staff to provide appropriate conditions for families and unaccompanied minors.

However, the Commission’s concerns about conditions in the Construction Camp have been exacerbated this year because of the significant increase in the number of people detained there. The Commission’s key concerns include the lack of open and grassy spaces inside the Construction Camp, the lack of indoor recreation space, the overcrowding, and the impacts this is having on families with young children. These issues are discussed in further detail in section 17 below.

This section provides a brief overview of access to appropriate education, recreational activities and food for children detained in the Construction Camp.

14.1 Access to education

Under international human rights standards, all children have a right to education.[125] This right should be recognised for all children in immigration detention. Children of compulsory school age should be provided with access to education of a standard equivalent to that in Australian schools. Children older than the compulsory school age should also be provided with opportunities to continue their education. Wherever possible, the education of children in detention should take place outside the detention facility, in the general school system.[126]

During its visit to Christmas Island, the Commission was pleased to observe that positive efforts are being made to provide many school-aged children with access to appropriate education. The Commission was informed that children detained in the Construction Camp who are aged 15 years or under attend the Christmas Island District High School on a daily basis. The Commission heard positive feedback from parents in detention about their children’s attendance and participation in classes at the local school. The Commission also visited the school and was pleased to observe asylum seeker children fully engaged in learning activities. Staff from the local school spoke highly of the support provided by DIAC. The Commission is also pleased that under a new initiative, some young adults detained in the Construction Camp are able to volunteer at the school as teacher’s aides.