3 Key issues emerging from the consultation

- Right to freedom of expression

- Right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion

- Right to freedom of association

- Property rights

The objective of Rights & Responsibilities 2014 was to actively seek and listen to people’s views across the country about how well their rights and freedoms are protected in Australia. This process provided an opportunity to identify systemic human rights issues and to consider possible ways to address these issues.

The key human rights issues outlined in this report reflect recurrent themes discussed at public events and meetings, and described in the online survey results and submissions. Data collected from meetings, survey responses and submissions was cross-referenced to ensure the information was valid and reliable. This triangulation of data sources supports the relevance and significance of these human rights issues. It is also notable that many of these human rights issues were consistent across the country.

Rights & Responsibilities 2014 focused on key common law rights and freedoms that traditionally underpin the framework of Australia’s liberal democracy and market economy, including the rights to freedom of expression, religion and association, and property rights. The importance of these rights and freedoms is also acknowledged in international human rights instruments.

The following sections of the report highlight:

- the issues emerging from the consultation in relation to each of these rights and freedoms

- the views of survey respondents about how well these rights are protected in Australia

- examples of people and organisations seeking to promote and exercise these rights and freedoms.

While freedom of expression, religion and association, and property rights are discussed separately in this report, the exercise of these rights is often interconnected. The interdependence of human rights means that the enjoyment of any individual right is contingent on the enjoyment of other rights. As Freedom 4 Faith note in their submission:

Religious freedom can only operate in a society that embraces the principle of mutual tolerance and respect. Further, it goes hand-in-hand with freedom of conscience, speech and association, which serve as the means by which people can consider, discuss and debate important questions about human existence. These “four freedoms” are essentially indivisible, and are each deserving of protection.

During Rights & Responsibilities 2014, additional issues and themes were raised that were outside the scope of the discussion paper. These recurring issues included concerns about:

- the right to freedom from arbitrary detention and the criminal justice system

- the denial of liberty for individuals in the mental health system

- the potential to give effect to a bill or charter of human rights in Australia.

A criticism of the consultation outlined in a number of submissions and raised at several public meetings was why the national consultation focused only on the rights to freedom of expression, religion, association and property rights. There was particular concern that the Rights & Responsibilities 2014 discussion paper did not seek to consult on the right to freedom from arbitrary detention as it relates to people seeking asylum in Australia.

The consultation deliberately did not focus on the right to arbitrary detention for the following reasons:

- The Commission has an extensive work program relating to asylum seekers, under the leadership of the President. This includes a complaints process.

- The consultation did not want to interfere with the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention being undertaken concurrently by the President during 2014.[8]

Issues raised about human rights and freedoms within the criminal justice and mental health systems – and potential implications for the right to arbitrary detention – are set out in this report.

Other issues emerging during the consultation included the need for further education about human rights. This was particularly highlighted because of the upcoming 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta on 15 June 2015. This is discussed in section 4 of this report.

Right to freedom of expression

I have felt that too often in recent times we have confused views we disagree with to views that should be illegal to verbalise.

We must be free to speak robustly about issues with which we do not agree.

The right to express is not a right to abuse. The right to an opinion is not a right to force that opinion on others.

Online survey responses

The right to freedom of expression provides the foundation for individual autonomy, the capacity for individuals to think for themselves and impart knowledge, and a strong democracy where opinions and ideas can be debated freely.[9] The right enables discussions and debates about political and social views, and in so doing, creates the basis for the effective exercise and defence of many other human rights and freedoms.[10] The right is:

closely linked to the rights to freedom of association, assembly, thought, conscience and religion, and participation in public affairs. It symbolizes, more than any other right, the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights. As such, the effective enjoyment of this right is an important indicator with respect to the protection of other human rights and fundamental freedoms.[11]

The right to freedom of expression is an extension of the right of freedom to hold opinions without interference.[12]

Freedom of expression applies to any medium, including written and oral communications, the media, public protest, broadcasting, artistic works and commercial advertising.

Based on interpretations of international human rights treaties, freedom of expression can be restricted in a limited range of circumstances. Such restrictions must be prescribed by law and be deemed necessary on the ground that it protects the rights or reputations of others, national security, public order, or public health or morals. A mandatory limitation also applies to the right to freedom of expression in relation to ‘any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence’.[13]

Freedom of expression in Australia

Survey results

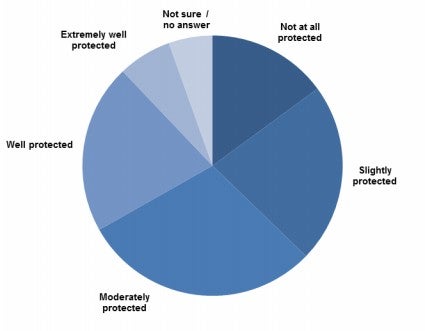

The survey asked respondents how well they think the right to freedom of expression (commonly referred to as free speech) is protected in Australia.

As shown in Figure 1:

- 28% of survey respondents believe the right to freedom of expression is extremely well or well protected

- 30% view the right to freedom of expression as moderately protected

- 37% think the right to freedom of expression is slightly or not at all protected.

These results – showing that 67% of participants view the right to freedom of expression as being moderately, slightly or not at all protected – suggest that there are concerns about the extent to which this right is protected in Australia.

Figure 1: How well do Australians think the right to freedom of expression is protected?

The ability to exercise our right to freedom of expression – and to open and informed debate – is a keystone to Australia’s democratic system.

The right to freedom of expression is not enshrined in federal legislation in Australia, be it through a charter of rights or otherwise. While the High Court of Australia has found that an implied right to freedom of political communication exists in the Australian Constitution, this protection of freedom of communication is ‘limited to what is necessary for the effective operation of [the] system of representative and responsible government’.[14]

In surveys, submissions and at meetings, people across the country noted concerns about the ways in which the federal and state/territory governments are infringing on people’s capacity to exercise free speech and participate in public policy debate.

Dissent, dialogue and even disagreement are cherished hallmarks of democracy but they are not always welcomed and encouraged. In recent years governments, aided and abetted by powerful interests, have consistently eroded freedom of expression in Australia. Online survey response

In [some] contexts, there may be restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression that cannot be justified. This is particularly so when freedom of expression is not just viewed as the simple right to speak, but as inextricably linked to the right to participate in public affairs... For those who are homeless and at risk of homelessness, the ability to exercise their freedom of speech in order to fully participate in Australian democracy is severely restricted by their disadvantage. Being excluded from mass media opportunities and from policy-making processes means that the voices of this group are effectively silenced when it comes to developing policy that will have a significant impact on their lives. Public Interest Advocacy Centre submission

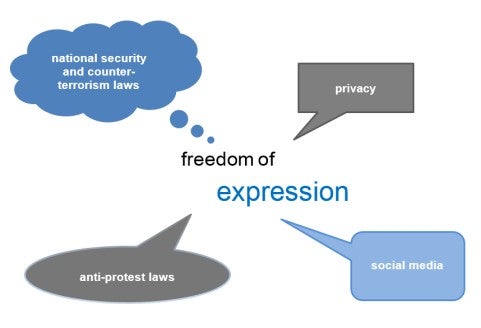

The following issues were identified as encroaching on people’s right to freedom of expression in Australia:

- anti-protest laws

- changes to federal and state government policies and funding that impact on the capacity of the community sector to participate in public policy discussions

- laws that limit speech and then prescribe the lawful basis for expression

- laws affecting freedom of the media.

Discussions also focused on privacy and ways in which the internet is used as an instrument to promote the right to freedom of expression.

Anti-protest laws

At meetings in South Australia, Tasmania, Queensland and Victoria, concerns were raised about anti-protest laws. As noted in the Human Rights Law Centre’s submission, ‘many of these anti-protest laws ... impact on freedom of speech’ and the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association. In particular, these laws restrict the capacity for people to debate and disagree on public policy matters, as well as limit the ability for people to express these views as a group.

Examples of anti-protest laws that were identified during the consultation were:

- Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Bill 2014 (Tasmania) – anti-protest laws criminalising legitimate forms of peaceful protest.

- Reproductive Health (Access to Terminations) Act 2013 (Tasmania) – access laws preventing persons from protesting within 150 metres of an abortion clinic.

- Amendments in 2014 to the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Victoria) – anti-protest laws expanding broad police powers to move people on from public space.[15]

- G20 legislation enacted in Queensland giving police broad powers to control protesters during the G20 summit in Brisbane in November 2014.

Mark Parnell MLC (South Australia) also highlighted the detrimental impact of Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation (SLAPP) practices on free speech in South Australia. SLAPP occurs where civil litigation is initiated in relation to a political issue in order to suppress community debate or stifle political activity. These practices effectively use litigation to stop people from exercising their right to protest.

Exercising the right to freedom of peaceful assembly should only be curtailed when necessary, with any restrictions proportionate to the legitimate aims of assembly. In this respect, freedom should be ‘considered the rule and its restriction the exception.’[16]

Anti-protest laws diminish our right to freely express our views with others. Restrictions on this require serious justification, and must be limited to only what is necessary.

Hindering the expression of views – even where others may strongly disagree with those beliefs – undermines the strength of Australia’s liberal democracy. Indeed, concern was voiced in several public meetings that adhering to ‘political correctness’ meant that people had lost the right to dissent from prevailing social and cultural opinions.

Community sector participation in public policy debate

In a participatory democracy all people should be able to have a voice. This includes people in service delivery such as community legal centres and others in the community sector being able to advocate and voice their experiences on the impacts of policy and laws on their client groups. Online survey response

At meetings with community legal centres and in submissions from the community sector, concerns were expressed about changes to federal government funding of legal centres. In particular, representatives from community legal centres claimed that being prohibited from using government funding to undertake law reform and advocacy work would severely restrict their ability to speak out on critical systemic work on access to justice.

The National Association of Community Legal Centres (NACLC) observed in its submission that additional cuts and changes to funding of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS), Legal Aid Commissions and Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services (FVPLS):

... [W]ill have significant effects as the law reform, policy advocacy and lobbying work of legal assistance providers is crucial in identifying and encouraging reform of laws, policies and practices that adversely or inequitably impact on disadvantaged people and vulnerable groups in the community. In addition, these changes raise concerns with respect to freedom of opinion and expression in Australia. NACLC submission

This issue highlights that there is a difference between having the freedom to express an opinion, and having the resources to develop an opinion and give it a platform.

Laws that limit speech and then prescribe the lawful basis for expression

Questions about where we draw the line of acceptable language were raised throughout the consultation, especially in view of the debate about proposed amendments to section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (RDA).

The views of participants were diverse, with some people wanting or accepting some change in the law, and some opposing change entirely.

Most of the debates focused on how to ensure that all groups in our society are protected from intimidating language and behaviour, while still enabling open discussion about controversial topics.

A number of participants in the consultation also raised whether protections, similar to section 18C of the RDA, should also be extended to groups of people on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity, and/or their religion. There was acknowledgement that the standard would have to be higher than ‘offend’, ‘insult’ and probably ‘humiliate’ to achieve public support for such a proposition.

There was also concern that the law over-reaches to restrict offensive expressions and then details the lawful basis for people to express views. Concerns were raised that the design of such a law leaves ambiguity about what is permissible expression.

Freedom of the media

Media plays a key role to enable Australians to exercise their right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to both express and receive information. As stated by Free TV Australia:

The information rights of the media and individuals are inherently related, and ensuring that the media is not unreasonably constrained in reporting is critical to maintaining a robust democracy. Free TV Australia submission

Submissions from Free TV Australia and the Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association (ASTRA) identified the following laws that encroach upon the right to freedom of expression:

- national security and counter-terrorism laws that restrict the content of material the media can report on and create penalties for journalists if these restrictions are breached

- defamation laws that can be used to force media outlets to remove material rather than be subject to lengthy legal procedures

- while freedom of information (FoI) laws enable access to documents that would otherwise be unavailable, protracted FoI processes can delay the media’s capacity to access information and report on issues in a timely manner.

These issues are expected to be considered by the Australian Law Reform Commission in its current inquiry into legislation that unreasonably encroaches upon traditional rights, freedoms and privileges.[17]

Privacy

Concerns were outlined about the extent to which changes to technology (for example, the development of surveillance devices) and government processes that seek to collect and retain personal information can impinge on our privacy.

These issues have been extensively addressed in the recent inquiry by the Australian Law Reform Commission into serious invasions of privacy.[18] A submission by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) also set out the regulatory and enforcement powers of the Privacy Commissioner, and the role of the OAIC in developing educational programs to promote a culture of respect for privacy.

The internet and social media

Access to information is a pre-requisite for the development and expression of ideas and opinions. In contemporary Australia, we are increasingly accessing information through the internet and social media.

The ways in which we exercise our right to freedom of expression through the internet and social media platforms – and where there should be limits – were discussed in almost all public meetings. Participants outlined issues about:

- ways to balance the right to free speech and the perception that people should be free of offensive expression

- where legislation should draw the line regarding free speech

- a definition of public harassment.

A submission from YMCA NSW articulated the potential of the internet to support free speech by empowering younger generations to challenge the acceptability of changes to language:

... [L]anguage change across generations [is] posing a challenge as to what is acceptable and unacceptable and therefore what might be considered offensive... In terms of advancing this right ... young people feel particularly empowered to execute this right given the role of technology in modern society. YMCA NSW submission

Conversely, a number of participants outlined concerns about the prevalence of cyber-bullying and its relationship to freedom of expression. At many meetings across the country, people shared stories about the detrimental impact of cyber-bullying on their personal and professional lives. The following quote summarises the issue:

Australians feel very strongly that they are free to express their opinions... However, when bullying and targeting arises as a reaction to that freedom of expression, it does impact on the sense of freedom the original person felt. Particularly online, threats and ‘trolling’ can deprive a person of the feeling of freedom to safely express themselves. This is complex because of course the ‘troll’ is exercising their right to freedom of expression, and in doing so limiting that of the other. Online survey response

These alternate views about the use of social media demonstrate the requirement for individuals to responsibly exercise their right to free speech. The view was expressed at several public meetings that anti-social behaviour such as cyber-bullying and ‘trolling’ occurred largely because anonymity allows people to not be responsible for their behaviour.

A case study demonstrating policies, tools and education resources developed by digital players to assist people engaging with social media platforms is outlined in the text box below.

Members of the Australian Interactive Media Industry Association (AIMIA) Digital Policy Group[19] – developing tools to assist consumers who use social media services

The digital industry seeks to provide platforms where people can share content, messages and ideas freely, while still respecting the rights of others. They work to achieve this balance by setting policies, investing in reporting infrastructure and liaising with governments, community groups and the public to help promote online safety.

Online service providers have developed initiatives to provide for the safety of people who use social networking services. These initiatives focus on:

- Policies which outline what people can and cannot do on platforms in clear, short and relevant language. Examples include The Twitter Rules[20] and Microsoft’s Terms of Use.[21] Many sites help bring terms of use to life by providing shorter more succinct explanations of community standards. Examples include Facebook’s Community Standards[22] and YouTube’s Community Guidelines.[23]

- Tools that allow people using services to make informed decisions about how they want to interact online and to help identify content that violates these policies. Some tools allow people to exercise choice about who they interact with online. These tools can include privacy settings for online profiles or tools to delete content, untag, block or mute others online. These tools also include tools to report content to the provider for review and removal where it violates the service’s content policies. For example, Yahoo7 provides tools to assist in reporting inappropriate or harmful behaviour via their ‘Report Abuse’ flags and the Abuse Help Form.[24] Facebook has developed a Support Dashboard,[25] so that people who report content can see the progress and outcome of the report.

- Education and awareness resources. Online safety requires community wide conversations. Digital platforms contribute to that conversation by providing education and awareness resources. Examples include the Google Good to Know[26] website as well as Yahoo7’s specialised safety website.[27] The leading platforms have also come together to develop the Keeping Australians Safe Online resource.[28]

Summary

Freedom of expression is an essential component of Australia’s liberal democratic system. However, there was significant concern throughout the consultation about government legislation and policies that undermine the capacity of individuals, the media and community to exercise their right to freedom of expression.

There was also concern that this resulted in the right to freedom of expression not being enjoyed and exercised equally by all individuals in our society. Particularly, there was a view that minority and more vulnerable individuals do not have an ‘equal’ platform to freely exercise their expression.

Potential ways to reform current legislative restrictions about freedom of expression were considered as part of the Free Speech 2014 symposium.[29] Following from the discussion generated at the symposium and concerns outlined during the consultation, the Human Rights Commissioner will continue to explore potential reforms in relation to current laws that restrict the right to freedom of expression.

Right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion

The value of protecting and promoting religious freedom is an essential and indivisible part of a broader program to safeguard fundamental freedoms for Australian society. Freedom 4 Faith submission

We need to have an understanding of different religions as [otherwise] we don’t know how to interpret behaviours. Attendee at meeting with Multicultural Community Services of Central Australia, Alice Springs

The freedom to hold beliefs of one’s choosing, to practice them and to change them is central to human development... We believe this freedom has a special place in safeguarding the dignity of the human being. Australian Baha’i Community submission

Freedom of religion in Australia

Survey results

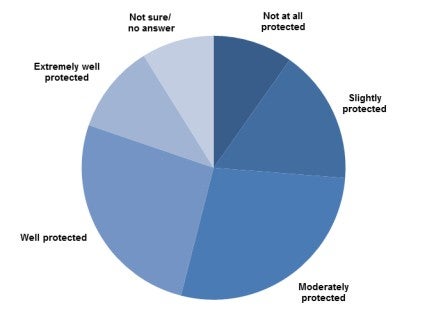

The survey asked how well respondents thought the right to freedom of religion is protected in Australia.

As illustrated in Figure 2:

- 37% of respondents viewed the right to freedom of religion as extremely well or well protected

- 44% thought religious freedom is either moderately or slightly protected

- 10% believe that religious freedom is not at all protected in Australia.

Figure 2: How well do Australians think the right to freedom of religion is protected?

Freedom of religion has limited protection in the Australian Constitution. Section 116 of the Constitution restrains the legislative power of the federal government and prevents one religion having pre-eminence over other beliefs.[32]

Consultation on the right to freedom of religion in Australia – and how it is exercised – revealed differing perspectives about the internal/private and external/public dimensions to religious freedom.

Several submissions cautioned against the use of ‘freedom of worship’ in the Rights & Responsibilities 2014 discussion paper as this term constrains the right to freedom of religion to the private sphere:

We note that Tim Wilson has sometimes used the term “freedom of worship” rather than “freedom of religion”, as if the two were synonymous. With respect, this appears to limit religious liberty to the private, or even semi-private sphere of private or congregational worship, and it is precisely this reduction in the scope of freedom of religion that is of concern to Freedom 4 Faith and other religious liberty advocates around the world. Freedom 4 Faith submission

Freedom of religion is constrained when restricted to “freedom of worship”. This restricts religion to Church, Synagogues or Mosques etc. To reject the “freedom of conscience” is to take away the right of a person to his/her religious beliefs... Catholic Women’s League of Victoria and Wagga Wagga submission

As outlined by the Australian Christian Lobby (ACL):

The concern about the concept of “freedom of worship” is that worship is an essentially private exercise. It is but one aspect of a person’s faith, and one that is largely exercised either individually or in the privacy of a congregational gathering. It fails to capture a large range of activity outside of worship. The much broader term “freedom of religion” allows for the reality that a person’s religious faith encompasses not only their private worship but their whole being, including their public activity. ACL submission

While the Human Rights Commissioner views ‘worship’ as more than just a private exercise, the intent of the use of this phrase was never designed to narrow discussion on religious freedom.

This tension between the extent to which the private right to worship extends into the public conduct of religious organisations and/or the public expression of religious beliefs was a consistent theme in discussions about religious freedom in Australia’s pluralist, multi-faith society.

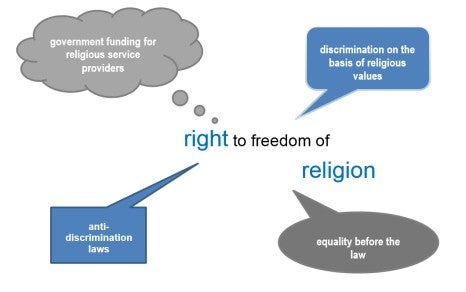

The following issues identified during the consultation process depict various ways in which the right to freedom of religion interacts with legislation and public policy:

- anti-discrimination laws

- government funding for religious organisations

- freedom of religion and equality before the law

- discrimination on the basis of religion.

Anti-discrimination laws

Anti-discrimination laws were identified as either failing to prevent discrimination against LGBTI people or impinging on the right to freedom of religion in Australia. For example, amendments made in 2013 to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) that prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status in a range of areas of public life, also include exceptions for ‘religious bodies’ and ‘educational institutions established for religious purposes’.[33]

Several submissions noted that federal and state anti-discrimination laws did not appropriately balance the prohibition of discrimination against LGBTI people and the protection of the right to freedom of religion. For example:

Many state and federal anti-discrimination laws include permanent carve-outs for religious organisations and individuals – including those that provide public services using public money – and permit discrimination that would otherwise be unlawful. Such carve-outs fail to achieve an appropriate balance between the rights to religious freedom and non-discrimination. Human Rights Law Centre submission

We do not believe that Australian law currently strikes the right balance between respecting the right to freedom of religious worship, and the harms caused by breaches of the right to non-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status. Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby submission

Conversely, submissions from some religious organisations argued that anti-discrimination laws encroach on freedom of religion. The ACL asserted that:

Because a hierarchy of rights is not widely recognized or defined in Australia, it is increasingly the case that conflicts are resolved at the expense of fundamental rights such as religion, conscience, speech and association...

Without adequate safeguards [anti-discrimination law] can result in the right to non-discrimination trumping other fundamental rights, including freedom of religion and freedom of speech. ACL submission

FamilyVoice Australia submitted that religious exemptions in anti-discrimination laws are ‘limited’ and have not protected religious organisations from the cost and disruption involved in dealing with complaints of discrimination.

Others argue that a balance of the competing rights to freedom of religion and freedom from discrimination reflects the responsible exercise of the right to freedom of religion:

A freedom of religious expression and respect for ethno-religious or religious affinity does not mean a freedom from scrutiny and freedom from responsibility. Bruce Arnold and Susan Priest submission

The enjoyment of a freedom should never be used to justify unacceptable discrimination. In return for being allowed to discriminate broadly against employees and students, religious educational institutions need to take seriously their responsibility not to do so unless absolutely necessary... WA Commissioner for Equal Opportunity submission

Government funding for religious organisations

The interaction between anti-discrimination laws and religious freedom was also raised during the consultation in relation to government funding religious organisations to provide services:

Religious organisations play a large and important role in public life in Australia; for example, in the provision of education, aged care and other services. The extent to which they are allowed to discriminate affects a significant number of people, including potential and existing employees and recipients of these services. PIAC believes that in this context, particularly where in receipt of public funding and where performing a service on behalf of government, religious organisations should not be permitted to discriminate in a way that would otherwise be unlawful. The wide-ranging permanent exceptions for religious organisations in federal anti-discrimination law allow for on-going discrimination in this context. Blanket religious exception from anti-discrimination law also means that in many cases the right of individuals is not properly considered vis-à-vis the right to freedom of religion. Public Interest Advocacy Centre submission

By allowing publically funded organisations to discriminate against certain groups, the Government sends a message that discrimination is acceptable in our community. This has the effect of entrenching systemic discrimination against vulnerable groups in our society. Kingsford Legal Centre, University of New South Wales submission

A particular concern raised in almost all public meetings was about the government funding of the National School Chaplaincy Program.[34] While there was general acknowledgement that the practice of the Program varied between schools, the issue was about the implications of government paying religious organisations to provide chaplaincy services in public schools that would otherwise be provided free at a place of worship:

The chaplaincy program ... restricts freedom FROM religion. A democratic government should be secular yet it has imposed a religious preference on all children regardless of their background. Online survey response [emphasis in original]

Harm is caused when the State supports one form of religious expression over another and when the State provides more favourable treatment to one form of religious expression over another. Rationalist Society of Australia submission

These concerns also raised questions about the extent to which religious organisations are able to enforce their beliefs when providing services that are funded by government. Examples discussed included whether religious organisations providing government funded education and/or health services should be able to:

- only employ staff who adhere to the religious beliefs of the organisation

- preference the provision of services to people of the religious faith.

Religious freedom and equality before the law

Equality before the law is a fundamental principle of human rights.[35] In Australia, the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) defines marriage as ‘the union of a man and woman’, which excludes same-sex couples and may also exclude people of intersex or diverse gender identity.[36]

A number of submissions highlighted the need for legislative reform:

... [T]o create marriage equality and bring an end to the discrimination currently faced by certain people in the community who would like to marry their partner, but are unable to do so simply because of their non-heterosexual status. Law Council of Australia submission

During the consultation, some members of religious organisations articulated concerns about the consequences for religious freedom if the federal government legislates marriage for same-sex couples. It is clear that any legislative reform needs to balance:

- equality before the law for same-sex couples to marry, and

- the human right to freedom of religion.

Concerns were raised from various religious communities that, should marriage for same-sex couples become lawful, some people may be compelled to act in a manner inconsistent with their faith.

As both the Human Rights Commissioner and the Commissioner responsible for SOGII, the future work of the Commissioner will involve on-going discussions with relevant people and organisations seeking to progress, amongst other relevant issues, equality before law for same-sex couples and advancing religious freedom.

Discrimination on the basis of religion

Several submissions outlined concerns about laws, policies and practices that have restricted freedom of religious worship. A view was expressed that:

... [F]ederal anti-terrorism and security laws introduced since 2001 have had a disproportionate and long-term discriminatory impact on Australia’s Islamic community. UnitingJustice submission

The particular impact of anti-terrorism laws on Muslim women is demonstrated by the ‘Ban the Burqa’ campaign in October 2014, which perpetuated an assumption that Muslim women are potential terrorists. The effect of this on Muslim women was articulated in the United Muslim Women’s Association’s submission:

... [D]iscrimination against Arab and Muslim Australians [is] most intensely felt by women ... due to the fact that Muslim women can easily be identified if they adhere to Islamic dress.

...

We are concerned that the rhetoric in public discourse and call for prohibitions against Muslim women’s dress is impinging on a Muslim woman’s right to freedom of religion. We are also concerned that fear in relation to safety concerns as a result of such treatment will further compromise the right to freedom of movement for Muslim women... United Muslim Women’s Association submission

There were examples given of discrimination on the basis of religion also occurring in the context of local council planning when members of the Muslim community seek to build mosques and/or Islamic schools.

There have been many instances in which planning applications for mosques (and Islamic schools) have been made to local councils and refused, especially after public outcry. It is concerning that the opposition to mosque building proposals has seen the expression of religious and racially discriminative views and vilification.

...

These cases highlight the insufficient protections for the right to freedom of religion and the complexity of intersectionality, in this instance, freedom of religion, the right to property and freedom of expression. UnitingJustice submission

Summary

The survey results suggest that the right to freedom of religion is relatively well protected, with only 10% of participants stating that religious freedom is not protected in Australia. Nonetheless, as described in this section, there are a number of areas where tension arises between the public expression of religious beliefs in a multi-faith, pluralist society, and its interaction with public policy.

As part of his future work priorities, the Human Rights Commissioner will form a religious freedom roundtable to bring together representatives of different faiths to facilitate how to advance religious freedom within public policy debate in Australia.

Right to freedom of association

Freedom of association cannot be simply a passive ‘right to belong’ to an organization. To be a meaningful right it needs to be an affirmative right. In the case of trade union membership, it must mean that workers can collectively pursue their rights and interests through their association with each other. Unions WA submission

These consorting laws, which prevent sex workers from working together ... deny sex workers the right to freedom of association and have obvious impacts on ... our access to mentoring, support networks and opportunities for advocacy and unionising. Scarlett Alliance submission

The right to freedom of association includes the right to form and join associations to pursue common goals and protect interests.[37] Associations comprise a diverse range of interests such as political parties, professional and sporting clubs, non-governmental organisations and trade unions.

Freedom of association supports other rights such as freedom of expression, religion, assembly and political rights, because the effectiveness of these rights and freedoms would be significantly diminished without the right to freedom of association.

The right limits the imposition of unreasonable and disproportionate restrictions by governments, including:

- preventing people from joining or forming an association

- imposing procedures for the formal recognition of associations that effectively prevent or discourage people from forming an association

- punishing people for their membership of a group.[38]

The right to form and join trade unions is specifically protected in international human rights treaties, which also articulate that the right to association includes the right to participate in the lawful activities of an association.[39] However, there is no settled interpretation of international treaties on whether the right to freedom of association encompasses the right not to be compelled to join an association, such as a trade union or professional association.[40]

Any limits to freedom of association must be prescribed by laws that are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals, or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.[41]

Freedom of association in Australia

Survey results

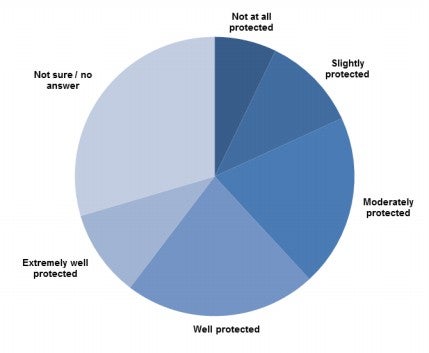

In the Rights & Responsibilities 2014 survey, participants were asked their view about how well they think the right to freedom of association is protected in Australia.

Results from the survey are shown in Figure 3 and highlight that:

- 24% of survey respondents consider that freedom of association is extremely well to well protected

- 39% believe that the right to freedom of association is moderately or slightly protected

- 16% view the right as not at all protected.

63% of participants responded that there is some level of protection of the right to freedom of association in Australia. Also, 21% of participants either were unsure or did not answer this question.

Figure 3: How well do Australians think the right to freedom of association is protected?

In Australia, there is no federal legislation that guarantees the right to freedom of association in all circumstances. There are, however, laws that protect elements of this right – such as industrial relations laws. The importance of freedom of association for a democratic society was recently reaffirmed by the High Court of Australia.[42]

The Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (Fair Work Act) protects freedom of association in the workplace by ensuring that persons are free to become, or not become, members of industrial associations.[43] This overcomes the gap in the international treaties concerning the absence of a right to not be compelled to join a trade union or professional association.[44]

The Australian Human Rights Commission Regulations 1989 (Cth) also prescribe ‘trade union activity’ as a ground for discrimination in employment. This means that, under the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth), the Commission can investigate complaints about discrimination in employment based on trade union activity.[45] This includes discrimination in circumstances where someone chooses to not be a member of a trade union.

The key issues that arose from the consultation in relation to the right to freedom of association were:

- anti-consorting laws

- trade unions and freedom of association in the workplace.

Anti-consorting laws

Several submissions expressed concern about the extent to which consorting offences curtail the right to freedom of association. The main area of concern was:

... [T]he emergence of new laws that increasingly criminalise association with people, rather than criminalise acts themselves. Human Rights Law Centre submission

Anti-consorting laws that were repeatedly mentioned during the consultation include:

- amendments to the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) on 9 April 2012 that place restrictions on ‘consorting’ with people who are convicted of an indictable offence

- the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act 2013 (Qld) and associated reforms that provide mandatory minimum sentences for members and associates of criminal gangs who commit offences as part of their participation in a gang

- the Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 (Western Australia) designed to give police and courts additional powers to deal with organised crime, including the ability to have a court declare an organisation to be a criminal organisation allowing for additional sanctions against its members.

Notably, the High Court confirmed in October 2014 that the Australian Constitution does not protect against the enactment of these laws.[46]

The Public Interest Advocacy Centre highlighted in its submission that all state and territory jurisdictions (except the ACT) have some form of anti-consorting laws. It highlighted the broader, national significance of these laws:

Anti-consorting laws by their very nature go beyond state and territory boundaries, not least because the acts constituting consorting will frequently involve interstate activities and actors. Public Interest Advocacy Centre submission

NACLC also raise concerns that anti-consorting legislation in NSW is:

... unduly broad, and that it has a “net widening effect” with unintended consequences for the most disadvantaged and marginalised people in NSW, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people experiencing homelessness. NACLC submission

Scarlet Alliance, the Australian Sex Workers Association, outlined how legislation – including anti-consorting laws – adversely impacts the association and employment conditions of sex workers:

Criminal and licensing laws prevent association between sex workers and restrict our abilities to organise and engage in political, industrial and collective advocacy. In some states, laws require private sex workers to work alone. These consorting laws, which prevent sex workers from working together, making referrals or hiring drivers, receptionists or security, deny sex workers the right to freedom of association and have obvious impacts on the safety of sex workers and our access to mentoring support networks and opportunities for advocacy and unionising. Scarlet Alliance submission

Trade unions and freedom of association in the workplace

Freedom of association in the workplace is protected in the Fair Work Act. The right of entry provisions of the Fair Work Act, which regulate trade union officials entering a workplace premises, were discussed in a number of meetings. The right of trade unions to enter premises can directly impact on the right of workers to join a trade union and assert their right to freedom of association in the workplace. The issue for both the business community and trade unions was about balancing the rights of:

- unions to represent their members in the workplace, hold discussions with potential members, and investigate contraventions of workplace laws and instruments

- employers to continue business without undue inconvenience

- employees to receive, at work, information and representation from union officials.

Amendments to the Fair Work Act that include changes to the right of entry framework are currently before the Senate.[47]

A related issue that was outlined during the consultation was the capacity for union enterprise agreements to specify an industry superannuation fund for employers to make contributions on behalf of their workers. The question was asked as to whether these agreements contravene the intent of the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Choice of Superannuation Funds) Act 2004 (Cth), which provides for employees to select their preferred superannuation fund.[48]

The importance of upholding the right to freedom of association in the workplace is outlined in the textbox below.

Cleaning Services Guidelines – United Voice and freedom of association

Cleaners who are members of United Voice raised concerns about their lack of access to freedom of association following the repeal of the Commonwealth Cleaning Services Guidelines (the Guidelines) on 1 July 2014.[49]

The Guidelines were established in 2011 to combat the poor record of employers in the cleaning sector. The Guidelines prescribed that companies who provided cleaning services to the government paid their cleaners above award rates of pay, and included mandatory practices for induction training, on the job training, safety, and fair and reasonable workloads.[50]

The Guidelines also mandated practices for acknowledging and supporting freedom of association and representation of employees. Employers were required to inform new employees about their choice regarding representation in the workplace and provide information about union membership and rights to collective bargaining. Employers were also required to make employees aware of consultation processes, dispute resolution processes, and the employee’s rights to have a representative of their choice in a dispute resolution process to deal with workplace issues.[51]

The Guidelines were revoked by the government on 1 July 2014 as part of its red tape repeals.[52]

At the Canberra Rights & Responsibilities public meeting, a cleaner who was originally from Angola told of her experience cleaning a Commonwealth building for over 30 years. She explained that during this time she had seen the treatment of cleaners get much worse, particularly in terms of knowing and understanding their right to join a union. Cleaners attending the meeting also stressed the importance of having this right set out in the Guidelines. This was especially important as many cleaners are women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds who work at the bottom of the labour market and do not have ready access to information about freedom of association.

As noted by United Voice, while ‘rights may exist they are useless if they are not accessible rights’.

Summary

The central issue in relation to the right to freedom of association is anti-consorting laws that criminalise the act of people associating with each other rather than their criminal activities.

Property rights

Central to the debate [about intellectual property rights] is the recognition of the importance of artists’ right to choose how, when and the manner in which their creative output will be made available to their fans – and how they can take steps to protect their rights when their choices are not respected... Music Rights Australia submission

... [T]he definition of the right to property should encompass a consideration of ... marginalized sections of society and their right to housing and an adequate standard of living in particular. NSW Young Lawyers Human Rights Committee submission

The right to property includes ownership and use of physical property, individuals’ ownership of their own bodies, and intellectual property. In modern legal systems, ‘property’ embraces every possible interest recognised by law which a person can have in anything and includes all valuable rights.

The right to own property includes the right:

- to own property alone as well as in association with others

- to acquire or dispose of property

- not to be arbitrarily deprived of their property.[53]

Property rights in Australia

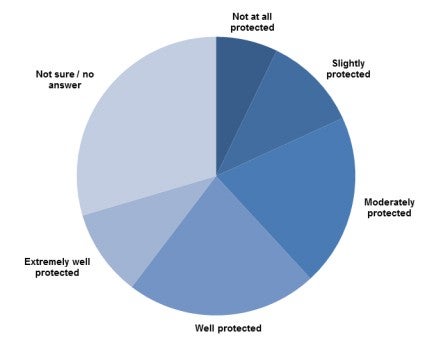

Survey results

The survey for Rights & Responsibilities 2014 asked the question: how well do you think the right to property is protected in Australia?

The survey results shown in Figure 4 show that:

- 32% of survey respondents believe that property rights are extremely well or well protected

- 31% view property rights as either moderately or slightly protected

- 7% state that property rights are not at all protected

- 30% of respondents were either unsure or didn’t answer.

While 63% of respondents believe there is some protection of property rights, almost a third of survey participants were either unsure or didn’t answer the survey question. In contrast, at public and strategic meetings, participants actively engaged in issues regarding their property rights.

Figure 4: How well do Australians think property rights are protected?

The right to property provides security, and enables opportunities for economic and social development.

Private property rights are recognised in section 51(xxxi) of the Australian Constitution, which guarantees that if property is acquired then just terms compensation will be paid by the federal government. Similar provisions do not exist at a state level.

The consultation exposed the following themes about how property rights affect the lives of Australians:

- access to affordable housing and homelessness

- government acquisition of land or regulation of land use

- the freedom to exercise native title

- intellectual property rights

- criminal confiscation laws.

Access to affordable housing and homelessness

Problems with access to affordable housing and the consequent increase in the number of homeless people,[54] were raised consistently throughout the consultation.

While personal factors such as domestic or family violence and/or financial difficulties may contribute to homelessness, an increase in housing stress is also occurring in all states and territories due to an undersupply of affordable housing.[55]

Issues about access to affordable housing and homelessness included concerns about the vulnerability of:

- younger people who fear they will never be able to afford to purchase a home

- people living in caravan parks who own their caravan but have no recourse to property rights if/when the caravan park owner decides to sell the land holding their caravan

- older people living in aged-care facilities where these facilities and/or families undermine their property rights and liberty

- people from refugee backgrounds who face discrimination in accessing rental properties

- older people who are long-term renters and have their rental lease terminated.

Recognising that employment underpins a person’s capacity to earn an income that enables them to afford a property, the Hutt St Centre in Adelaide has developed education and employment programs to support people who are homeless – see textbox below.

Hutt St Centre – tackling homelessness and the Pathways to Employment initiative[56]

The Hutt St Centre (HSC) in Adelaide assists people to realise their right to property by helping them access and move into their own homes. More recently, the HSC has introduced Pathway Programs (Education & Employment) to help build employability skills and job prospects leading to improved social and economic participation and prosperity.

The HSC has found that people who have access to stable housing are able to undertake and complete studies, as well as obtain and maintain employment.

The HSC also delivers social, recreational and education courses to people who have experienced homelessness. This assists people to build life skills such as cooking and budgeting, to develop IT skills and to undertake further education. In 2013-14, the HSC assisted more than 40 participants to undertake further qualifications, from unaccredited courses to diploma and university courses.

Pathways to Employment is the HSC’s employment program that assists participants to access employment. This eight week program supports participants to identify and achieve their employment goals by breaking these down into small steps. For example, participants develop a resume, cover letter, obtain identification, undertake education such as forklift licenses or first aid; they are supported through the job application process, coached through the interview, and then supported to maintain their position.

Since Pathways to Employment started in 2013, 65 participants have obtained employment, keeping them out of homelessness and enabling them to earn a sufficient income to afford long term, stable accommodation.

During his term, the Human Rights Commissioner will undertake further work examining access to affordable housing in Australia.

Government acquisition of land or regulation of land use

A recurring theme from the consultations was the way in which state/territory government policies and legislation impact on the property rights of individuals. Concerns generally reflected governments either:

- permitting access to land without adequate consultation or compensation, or

- limiting how individuals may use their private property.

In meetings in Western Australia, Queensland and NSW, landholders and coal seam gas mining companies described their competing rights to surface and sub-surface property. Tensions occurred when state governments permitted mining interests access to sub-surface resources (coal seam gas) without considering the interests of the landholders using the surface property. Meetings in Roma and Singleton highlighted the importance of government and mining interests:

- engaging with local communities and consulting landholders

- recognising landholders’ property rights

- providing adequate compensation to landholders where there are adverse impacts on property rights.

In Western Australia, concerns were raised about government regulations hindering people’s capacity to use their private property. For example, participants raised issues with provisions of the Environmental Protection Act 1986 (WA). These provisions, which restrict land clearance, adversely affect the capacity of landholders to farm their land but do not provide any compensation.[57] In a number of meetings, there were also reports about the impact on landholders affected by arbitrary land clearance decisions who then had limited recourse to independent review of these decisions. These stories demonstrated not only potential problems about processes of natural justice, but also the devastating social and economic consequences for farmers unable to earn a living from their property.

At a number of public meetings, individual property rights were contrasted with a claimed community ‘right to a healthy environment’ (for example, see the EDO Tasmania submission). The submission from the Law Society of NSW Young Lawyers offered support for a balance between private property rights and environmental protection:

... [F]or instance, the ability of government to respond to the very real threat of climate change and the need for the protection of our natural environment, which affects numerous human rights, would be hampered were the right to property to be interpreted in such a way that limited the ability of government to respond to these pressing environmental issues of our time. Human Rights Committee, Law Society of NSW Young Lawyers submission

The freedom to exercise native title

Native title recognises the rights and interests in lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Native title is inalienable, meaning that it cannot be traded or sold – unlike freehold title. The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) does, however, enable native title holders to negotiate agreements that can include the surrender of native title, access to other forms of title or compensation.

Consultations with native title holders revealed that they face complex legislative and bureaucratic regulations that impede their capacity to use their native title to achieve economic development. These barriers obstruct the potential for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to build and own houses on their native title lands, and use their native title as a foundation to create and participate in businesses. Many of these issues have been set out in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner’s annual native title reports to the federal Parliament.[58]

Some of the barriers facing native title holders seeking to use their native title to create opportunities for economic development are outlined in the case study on the Yawuru People’s native title determination in the textbox below.

Yawuru Peoples – native title and economic development

The 2006 Yawuru native title determination provides the cultural foundation for the Yawuru people to participate in the local and global economy.[59] The subsequent Yawuru Native Title Global Agreement (2010) (Yawuru Agreement) enables the Yawuru to generate income from developable land as well as return social and economic benefits to native title holders and other Indigenous people in the Broome region.

In accordance with the Yawuru Agreement, the Yawuru consented to extinguish their native title rights over significant parts of their traditional land estate to enable the urban and commercial expansion of the Broome region. As compensation for this and other past acts of extinguishment, the Yawuru gained substantial freehold title in and around Broome as a basis for future income generation, and other lands for cultural and conservation purposes.

This was to create opportunities for Yawuru and other Indigenous people in the Broome region to dramatically improve their social and economic position through innovative housing development on Yawuru land; employment in the rapidly growing energy industry; enterprise engagement in cultural and ecological tourism; a range of land and marine management initiatives; and participation in delivering social services.

However, the Yawuru and other Indigenous people have not been able to fully realise these economic development opportunities from their native title. There have been two main impediments:

- The Yawuru Agreement has placed a substantial burden on the Yawuru in terms of a range of imposts such as land tax, local government rates and development costs that have significantly eroded the Yawuru’s development capacity.

- Despite broad philosophical support by federal, state and local governments for partnership building with the Yawuru, there has been limited capacity to forge partnerships with public and private capital. The complexity of the native title system has caused difficulties in negotiating mutual beneficial partnerships with all levels of government and industry in the areas of housing, employment, enterprise creation, and individual and community capability development.

The Human Rights Commissioner will jointly facilitate a high-level forum with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner to discuss reforms that remove legal and regulatory barriers faced by native title holders seeking economic development.[60]

Intellectual property rights

The extent to which intellectual property rights are protected in Australia was discussed during the consultation. For example, the following comments were made in relation to protection from music theft legislation and online copyright infringement:

Current copyright laws do not contain adequate protections for fair use for comment and artistic expression. Online survey response

The internet is central to the music industry and offers artists new exciting avenues to find new audiences and connect with their fans but it should not also be allowed to stop them getting a fair return for their artist output. Ross Wilson submission

In Australia today there is no efficient or practical way for a copyright owner to protect their music online if someone wants to take it without respecting their choice about how it will be made available to the public. Music Rights Australia submission

I also expect the government to protect my work from theft, the same way they protect every other retail product that I can think of. Tina Arena submission

Intellectual property rights were also raised in Alice Springs in relation to recognising and protecting Aboriginal peoples’ traditional knowledge:

- Papunya Tula Artists,[61] demonstrates the benefits of Aboriginal artists having a cooperative and community approach to producing and selling their art. The Royalty Resale Scheme,[62] which enables artists to receive royalties on certain resales of their work, also recognises the long-term value of artwork and provides money to artists that would otherwise not occur.

- Ninti One is developing projects that recognise the intellectual property rights of Aboriginal peoples’ traditional knowledge – see text box below.

Ninti One – intellectual property rights and traditional knowledge

Established in 2003, Ninti One is an independent, national not-for-profit company that builds opportunities for people in remote Australia through practical research, innovation and community development.

Ninti One manages the research and partnerships of the Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation (CRC-REP), which is focused on delivering solutions to the economic challenges that affect remote Australia. Two research projects being carried out by CRC-REP are investigating issues relating to intellectual property rights agreements, policies and legislation:

- The Plant Business project is developing a model for improving native plant varieties to make horticultural production of bush foods more efficient and profitable. The focus is on sustained growth of value of the Bush Tomato trade as a case study, to increase business opportunities for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A significant theme of the research is a detailed analysis of the variety of approaches available for safeguarding the needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people associated with Traditional Knowledge being commercially utilised. Strategies including conventional legal approaches, international protocol compliance, trademarks, certification and Knowledge Trusts will be explored. This will deliver tools to assist in maximising benefit sharing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the utilisation of cultural heritage.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Economies Project is undertaking wide-ranging analysis of key points in the supply chain connecting remote area artists with agents and national audiences. The creative industries sector is characterised by complex and unresolved intellectual property issues in relation to communal knowledge (cultural knowledge that is simultaneously shared and also utilised by authorised individual artists) and ongoing copyright infringements. Research work has also highlighted other intellectual property issues. One research area, working with freelance artists (independent, ‘sole-trader’ artists working with a range of agents) identified that while many of these artists feel confident in negotiating with agents on a day-to-day basis, there was very limited awareness of key intellectual property issues and almost no knowledge of how to access support or advice in resolving these issues. Access to cultural resources by artists in areas where national parks or other conservation measures are in place has also been identified as an issue. Ongoing cultural practices, including the right to access cultural livelihoods are limited by regulations, regardless of ongoing association to the land and resources.

Criminal confiscation laws

Property rights may be undermined by disproportionate criminal confiscation laws, which provide for the forfeiture of all assets owned by a person who is declared a ‘drug trafficker’.[63] The submission from the Australian Lawyers Alliance noted:

... [C]riminal confiscation laws in the Northern Territory and Western Australia are currently grossly disproportional to an offence, and deeply impact upon an individual and their family’s rights to own property and for any acquisition to be on “just terms”.

Further, laws in the Northern Territory permit the:

... [F]orfeiture of all property owned by an individual, even if the property was not used for, or derived as a result of criminal activity. Australian Lawyers Alliance submission

Summary

The consultation presented a wide range of issues and questions in relation to property rights. The significance of property rights was demonstrated by the breadth of issues raised in public and strategic meetings across the country.

The Human Rights Commissioner will focus on the following areas during his term:

- access to affordable housing for all Australians

- jointly facilitate a high-level forum with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner to discuss reforms that remove legal and regulatory barriers faced by native title holders seeking economic development.

[8] G Triggs, President, The Forgotten Children: Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Australian Human Rights Commission (2015). At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/forgotten-children-national-… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[9] The right to freedom of expression is set out in Articles 19 and 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Articles 4 and 5(d)(viii) of the International Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; Articles 12 and 13 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; and Article 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities.

[10] Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 34 Article 19: Freedom of opinion and expression International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, paras 2 and 4. At http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/TBSearch.aspx?L… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[11] F La Rue, Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of expression and opinion, UN Doc: A/HRC/14/23, 20 April 2010, para 27.

[12] Attorney General’s Department, Right to freedom of opinion and expression. At http://www.ag.gov.au/RightsAndProtections/HumanRights/PublicSectorGuida… (viewed 3 March 2015).

[13] Article 20(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

[14] Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 145 ALR 96.

[15] As at 12 March 2015, the Summary Offences Amendment (Move-on Laws) Bill 2015, which repeals restrictive laws regulating protests, has passed the Victorian Legislative Assembly and is before the Legislative Council.

[16] M Kiai, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, UN Doc: A/HRC/23/39, 24 April 2013, para 47.

[17] Australian Law Reform Commission, Freedoms Inquiry. At http://www.alrc.gov.au/inquiries/freedoms (viewed 17 February 2015).

[18] Australian Law Reform Commission, Serious Invasions of Privacy (2014). At http://www.alrc.gov.au/inquiries/invasions-privacy (viewed 17 February 2015).

[19] The Australian Interactive Media Industry Association Digital Policy Group (AIMIA) represents 460 digital players in the Australian digital industry, with membership of the AIMIA Digital Policy Group’s Cyber-safety Sub-group including Yahoo!7, Google, Facebook, eBay, Microsoft and Twitter.

[20] The Twitter Rules. At https://support.twitter.com/articles/18311-the-twitter-rules# (viewed 17 February 2015).

[21] Microsoft, Terms of Use. At http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/legal/intellectualproperty/copyright/def… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[22] Facebook, Community Standards. At https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards (viewed 17 February 2015).

[23] YouTube, Community Guidelines. At https://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines (viewed 17 February 2015).

[24] Yahoo7, Abuse Help Form. At https://au.help.yahoo.com/kb/reporting-abuse-yahoo-messenger-sln494.html (viewed 17 February 2015).

[25] Facebook, Support Dashboard. At https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook-safety/more-transparency-in-rep… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[26] Google, Good to Know. At https://www.google.com/intl/en-AU/goodtoknow/ (viewed 17 February 2015).

[27] Yahoo7, Safely. At https://au.safely.yahoo.com/ (viewed 17 February 2015).

[28] AIMIA, Keeping Australians Safe Online. At http://www.cybersmart.gov.au/cybersmart-citizens/~/media/Cybersmart/Dig… (viewed 25 February 2015).

[29] Australian Human Rights Commission, Free Speech 2014 Symposium Papers (7 August 2014). At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/publications… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[30] The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion is set out in Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article 5(d)(vii) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; and Article 14 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

[31] ‘Absolute’ human rights means that they cannot be limited for any reason.

[32] The High Court of Australia has generally adopted a narrow view of the scope of section 116. For example, it held that a law providing for financial aid to the educational activities of church schools was not a law for establishing a religion, even though the law might indirectly assist the practice of religion, and accordingly, the law was not in breach of section 116 (Attorney-General (Victoria); Ex rel Black v The Commonwealth (1981) 146 CLR 559).

[33] Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth), ss 37 and 38.

[34] Changes to the National School Chaplaincy Program were made following the High Court decision in June 2014. Funding of the Program is now delivered via the states/territories education budget. Details of the program are available at https://education.gov.au/national-school-chaplaincy-programme (viewed 17 February 2015).

[35] For example, Article 7 of the United Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law’.

[36] Marriage Act 1961 (Cth), s 5.

[37] The right to freedom of association is set out in Article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article 8(1)(a) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Article 5 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; Article 15 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; and Article 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

[38] Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, Guide to Human Rights, Commonwealth of Australia (2014), p 39. At http://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/Committees/Joint/PJCHR/Guide%20to%20Human… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[39] For example, see Article 8(1)(c) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and Article 3 of the International Labour Organisation Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention (1948).

[40] Attorney-General’s Department, Right to Work and Rights at Work. At http://www.ag.gov.au/RightsAndProtections/HumanRights/PublicSectorGuida… (viewed17 February 2015).

[41] See Article 22(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

[42] Unions NSW v New South Wales [2013] HCA 58.

[43] Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), s 336.

[44] Attorney-General’s Department, Right to Work and Rights at Work. At http://www.ag.gov.au/RightsAndProtections/HumanRights/PublicSectorGuida… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[45] Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth), s 46P.

[46] Tajjour v New South Wales; Hawthorne v New South Wales; Forster v New South Wales [2014] HCA 35.

[47] Parliament of Australia, Fair Work Amendment Bill 2014. At http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Se… (viewed 17 February 2015).

[48] J Sloan, ‘Workers must be free to choose where superannuation goes’, The Australian, (16 September 2014).

[49] Commonwealth Cleaning Services Guidelines Repeal Instrument 2014 (repealed 28 June 2014). At http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2013L00435/Explanatory%20Statement/Text (viewed 2 February 2015).

[50] Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Best Practice Updates – revocation of the Commonwealth Cleaning Services Guidelines and the Fair Work Principles Regulation Impact Statement, Australian Government. At http://ris.dpmc.gov.au/2014/07/10/revocation-of-the-commonwealth-cleani… (viewed 20 February 2015).

[51] Commonwealth Cleaning Services Guidelines, s 5. At http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2013L00435/Download (viewed 20 February 2015).

[52] Commonwealth Cleaning Services Guidelines Repeal Instrument 2014 (repealed 28 June 2014). At http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2013L00435/Explanatory%20Statement/Text (viewed 2 February 2015). Department of Employment, Revocation of the Fair Work Principles and the Cleaning Services Guidelines, (20 March 2014). At http://employment.gov.au/news/revocation-fair-work-principles-and-commonwealth-cleaning-services-guidelines (viewed 9 February 2015).

[53] The right to property is set out in Article 17 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights; Article 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights; Article 21 of the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights; and Article 14 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights.

[54] There are currently 105 237 homeless people in Australia; between 2006 and 2011, the number of homeless people increased by 17%. See B Taylor, Rights to Property and Homelessness in Australia, Hutt Street Centre, paper provided to the Australian Human Rights Commissioner, 31 October 2014.

[55] B Taylor, Rights to Property and Homelessness in Australia, Hutt Street Centre, paper provided to the Australian Human Rights Commissioner, 31 October 2014.

[56] B Taylor, Rights to Property and Homelessness in Australia, Hutt Street Centre, paper provided to the Australian Human Rights Commissioner, 31 October 2014.

[57] Environmental Protection Act 1986 (WA), ss 51A-51T.

[58] For example, see T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Reports 2005, 2006, 2007, Australian Human Rights Commission; and M Gooda, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2012, Australian Human Rights Commission (2012). At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/aboriginal-and-torres-strait… (viewed 5 March 2015).

[59] M Gooda, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2012, Australian Human Rights Commission (2012), pp 109-112; Yawuru PBC Annual Report 2013, ‘Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation’ (2013).

[60] The issues that will be addressed at this forum are different to the issues considered by the Australian Law Reform Commission in its inquiry into specific areas of native title – see http://www.alrc.gov.au/inquiries/native-title-act-1993 (viewed 12 March 2015). This forum will compliment the current COAG investigation into Indigenous land administration and use – see https://www.dpmc.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/about/jobs-land-and-economy-… (viewed 12 March 2015).

[61] Papunya Tula. At http://papunyatula.com.au (viewed 17 February 2015).

[62] Attorney General’s Department Ministry of the Arts, Royalty Resale Scheme. At http://arts.gov.au/visual-arts/resale-royalty-scheme (viewed 17 February 2015).

[63] Attorney General [NT] v Emmerson [2014] HCA 13.