3. Setting the Scene - Children in Immigration Detention

A last resort?

National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention

3. Setting the Scene - Children in Immigration Detention

I want to tell you that actually I spent about fifteen nights in the ride to Australia. I was in a small boat if you want to call that a boat, because it was smaller than that, with lots of difficulties. When I saw [we were] getting near Australia I was becoming a little bit hopeful. When we passed Darwin I got to the detention centre as soon as I looked at these barbed wires my mind was full of fear. That was the time that I experienced fear ... When after all the negative experiences that I had in the detention centre, when I was released I felt like a normal human being and I felt that I was coming back to life!

Unaccompanied Afghan boy found to be a refugee(1)

I believe you [Australians] are nice people, peace seekers, you support unity. If you come to see us behind the fence, think about how you would feel. Are you aware of what happens here? Come and see our life. I wonder whether if the Government of Iran created camp like Woomera and Australians had seen pictures of it, if they would have given people a visa to come to Australia then.

Unaccompanied child refugee, formerly in Woomera(2)

This chapter attempts to provide some context to a discussion of the human rights of children in immigration detention centres in Australia by shedding light on who the children are, where they came from and what they think about their detention experience.

As well as capturing current and former detainee children's voices, this chapter contains facts and figures on children in immigration detention. It does not attempt to explain the reasons for detention, which are considered in detail in Chapter 6 on Australia's Detention Policy.

Almost all of the statistical material contained in this chapter was supplied by the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (the Department or DIMIA). Where the statistics come from other sources, those sources are noted.

This chapter addresses the following questions:

3.1 Where can children be detained?

3.2 How many children have been in immigration detention?

3.3 How many detainee children have been recognised as refugees?

3.4 How long have children been in immigration detention?

3.5 What is the background of children in immigration detention?

3.6 How did the children get to the detention centres?

3.7 What did children and their parents say about detention centres?

3.1 Where can children be detained?

Prior to September 2001, children arriving on Australian territory (including Australian territorial waters) without a visa could be detained in any one of the following detention facilities: Curtin Immigration Reception and Processing Centre (IRPC), Port Hedland IRPC, Woomera IRPC or the Woomera Residential Housing Project (RHP), Christmas Island IRPC, Cocos (Keeling) Islands Immigration Reception Centre (IRC), Villawood Immigration Detention Centre (IDC), Maribyrnong IDC and Perth IDC.

Some of these detainees were transferred to Baxter Immigration Detention Facility (IDF) after September 2002.

After September 2001 asylum-seeker children who arrived on Christmas Island, the Ashmore Islands or the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, or who were intercepted by Australian authorities, were usually transferred to detention centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

From 1998 Australasian Correctional Management Pty Limited (ACM) provided detention services in all Australian detention centres. In 2004, another company (Group 4 Falck) took over this role.

3.1.1 Baxter Immigration Detention Facility

Baxter opened in July 2002, with the first detainees arriving on 6 September 2002. It is 12 km outside Port Augusta, a rural town 275 km north of Adelaide, South Australia. The facility's nominal capacity is 1160.(3) Within three months of opening there were 41 detainee children in a total population of 218 detainees.(4) As at December 2003, the maximum number of children detained in Baxter at any one time was 54 out of 248 detainees, on 2 January 2003.(5)

Baxter was a planned detention centre, intended by the Department to solve many of the problems facing children and families in the other facilities. The Woomera RHP was managed from Baxter once Woomera detention centre had closed.

On 19 November 2003 a residential housing project opened at Port Augusta West. As at 12 December 2003, 10 detainee women and 17 children had been transferred there from the Baxter facility and the Woomera RHP.(6)

Exterior view of Baxter Immigration Detention Facility, December 2002.

3.1.2 Curtin Immigration Reception and Processing Centre

The Curtin detention centre was situated outside the town of Derby in the West Kimberley, Western Australia, 2643 km north-west of Perth.(7) The site was recommissioned from the Curtin Air Base for immigration detention in September 1999. The detention centre was 'mothballed' on 23 September 2002 and most of its detainees were moved to Baxter.

Curtin's nominal capacity was 1200 detainees, although in January 2000 it exceeded that capacity. The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 200 out of a total population of 894 on 1 April 2001.(8)

3.1.3 Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre

The Maribyrnong facility, situated in Melbourne, Victoria, opened in 1966. Like the Villawood and Perth detention centres, it mainly caters for visa overstayers and those whose visas are cancelled because they have failed to comply with their visa conditions. People refused entry to Australia at international airports and seaports are also detained there. Its nominal capacity is 80. The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 13 children out of 71 detainees on 1 February 2001.(9)

3.1.4 Perth Immigration Detention Centre

The Perth facility, adjacent to Perth Airport, Western Australia, opened in 1981. The centre is small, with a capacity of 64 detainees, and mainly caters for visa overstayers. The building was built as a single level secure facility for the Australian Federal Police, but was converted shortly afterwards to an immigration detention facility. Very few children are detained there, and those who are generally only stay a few days. However, the Department's web site states that 'Perth IDC was recently upgraded and refurbished to improve the layout, amenity and capacity, particularly for women and children'.(10)

3.1.5 Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre

The Port Hedland facility, on Western Australia's northern coast, 1638 km from Perth, was established as a detention centre in 1991, having been built in the 1960s as accommodation for single men in the local mining industry. Its nominal capacity is 820 detainees.(11) The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 177 out of a population of 636, on 1 September 2001. However, Port Hedland's largest population was on 1 January 2000, when there were 839 detainees of whom 90 were children.(12)

On 19 September 2003, the Department opened a residential housing project in Port Hedland. As at 12 December 2003, one woman and two children had been transferred there.(13)

View through the perimeter fence at Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre, June 2002.

3.1.6 Villawood Immigration Detention Centre

The Villawood facility, situated in the western suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, opened in 1976. It has a nominal capacity of 700 detainees, and mainly caters for visa overstayers. The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 47 out of a population of 360 detainees, on 1 March 2001.(14)

3.1.7 Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre

The Woomera facility is situated just outside the remote town of Woomera, in the Simpson Desert in South Australia, 487 km from Adelaide. It opened in November 1999 and was 'mothballed' in April 2003.(15)

Woomera's nominal capacity was 1200, but from March to July 2000 the population was above that number.(16) The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 456 children out of a population of 1442 detainees, on 1 September 2001.(17)

External view of Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre, June 2002.

3.1.8 Woomera Residential Housing Project

The Woomera RHP opened on 7 August 2001. It originally had a nominal capacity of 25 detainees. In May 2003, the Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (the Minister) announced the expansion of the housing project to a capacity of around 40 detainees.(18) The maximum number of children detained there at any one time was 15, on 1 March 2002.(19) By June 2003, there were just seven children detained there.(20) The same number of children was there in November 2003.(21)

Women and children are detained in a cluster of houses in a street in the Woomera township. They are under supervision at all times by ACM officers. The housing project is open to women and girls (of all ages). Prior to September 2003, only boys under the age of 13 could apply for a transfer there.(22)

3.1.9 Christmas Island Immigration Reception and Processing Centre

Christmas Island is part of the Australian Indian Ocean Territories, 2300 km northwest of Perth, a four-hour flight away. A temporary facility based at Phosphate Hill opened on 13 November 2001, with a nominal capacity of 500, although it has exceeded its capacity at times. Unauthorised arrivals were detained in Christmas Island's sports hall with tents set up next to it, as required, until December 2001.

The maximum number of children detained on Christmas Island at any one time was 160 out of a population of 529, on 1 December 2001.(23) After September 2001 most arrivals were transferred to Nauru or Papua New Guinea.

In 2002, the Government announced plans to build a permanent facility capable of housing 1200 detainees at a capital cost of $230 million. Subsequently this was downgraded to an 800 detainee facility. Completion is not expected before 2005. The existing facility was 'mothballed' on 19 March 2003,(24) and then recommissioned in July 2003 when 53 Vietnamese asylum seekers were detained there.

3.1.10 Cocos (Keeling) Islands Immigration Reception Centre

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands are part of the Australian Indian Ocean Territories, south of Indonesia, about half-way from Australia to Sri Lanka. They are a four and a half hour flight from Perth. On 15 September 2001, a former Animal Quarantine Station on West Island opened as a detention centre for unauthorised arrivals. West Island is small and isolated with basic infrastructure. At the time of the Inquiry's visit in January 2002, the facility was holding 131 detainees (122 men, four women, three boys and two girls). The detention centre closed on 24 March 2002.

3.1.11 'Pacific Solution' detention centres

Since September 2001, when the Australian Government introduced the so-called 'Pacific Solution', children who arrived in Australia's 'excised offshore places' (including Christmas Island, Ashmore and Cartier Islands, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands) have been detained at Christmas Island or transferred to the 'offshore processing centres' on Manus Island and Nauru.(25) Manus Island is part of Papua New Guinea (PNG) and lies in the Bismarck Sea, north of the PNG mainland. Nauru is an island nation in the South Pacific Ocean.

The operation of the detention services on Manus Island and Nauru is contracted to the International Organisation for Migration. The Australian Government conducts refugee status processing in those detention centres.

As set out in Chapter 2 on Methodology the Inquiry requested that the Department facilitate a visit to Nauru or Manus Island so that it could interview the children and families there. The Department declined the request and has not provided any statistics on the children detained there.

3.1.12 Other places of detention

Under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act), detainees can be held in any place approved by the Minister in writing, for example, a hospital, motel room, prison or private home.(26) The conditions in these facilities vary from place to place.

From late January 2002, most unaccompanied children were transferred from the Woomera and Curtin facilities to foster homes in Adelaide, which were declared 'alternative places of detention'.(27) As at 13 December 2002, there were 24 children in alternative places of detention such as private apartments or foster care. Three of the 24 children were under the age of 12, and nine were unaccompanied children.(28)A year later, as at 26 December 2003, 12 children were in alternative places of detention. Seven of these children were in foster care. Two of these children were under ten years of age, the remaining ten children were between 15 and 17-years-old. Eight of these children were unaccompanied children.(29)

3.2 How many children have been in immigration detention?

The total number of persons who have arrived in Australia by boat without a visa (unauthorised boat arrivals), since November 1989 is 13,593.(30) To put this number in perspective, all of the unauthorised boat arrivals in Australia over the last 14 years, when gathered together, would fill approximately 15 per cent of the seating capacity of the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Since 1992, all of these arrivals were mandatorily detained under Australian law - some for weeks, some for months, and some for years.

In Australia, 976 children were in immigration detention in the year 1999-2000, 1923 children in 2000-2001, 1696 children in 2001-2002 and 703 children in 2002-2003.(31)Most of these children arrived by boat.(32) The total number of children who arrived in Australia by boat or air without a visa (unauthorised arrivals), and applied for refugee protection visas between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003 was 2184.(33) These figures do not include children transferred to and detained on Nauru and Manus Island.(34)

The highest number of children held in detention at any one time between 1 January 1999 and 1 January 2004 was 842 on 1 September 2001. Of those children, 456 were at the Woomera detention centre.(35)

The lowest number of children in detention at any one time during the same period was 49 on 1 February 1999 and again on 1 May 1999. Most of these children were at the Port Hedland and Villawood detention centres.(36)

At the time the Inquiry was announced, in late November 2001, there were over 700 children in immigration detention.(37) By the time of the Inquiry's public hearing with the Department a year later, the number had reduced by 80 per cent to 139.(38) The number of children in detention has not decreased at the same rate since that time. There were still over one hundred children in immigration detention in May 2003.(39)As at 26 December 2003, there were 111 children in detention in Australia.(40)

The following four tables set out the numbers of children taken into immigration detention, where they were detained and the reason for detention from 1 July 1999 - 30 June 2003. The tables illustrate that child boat arrivals have been primarily detained in the remote facilities of Curtin, Port Hedland and Woomera, until 2003 when most boat arrival children were transferred to Baxter.(41)

Table 1: Children in immigration detention by method of arrival: 1999-2000

| Children in detention 1999-2000 | Overstayed visa | Boat arrival with no visa(43) | Air arrival with no visa | Other(42) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtin | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 200 |

| Port Hedland | 8 | 258 | 20 | 0 | 286 |

| Woomera | 0 | 248 | 0 | 0 | 248 |

| Villawood | 26 | 7 | 100 | 13 | 146 |

| Maribyrnong | 7 | 2 | 41 | 0 | 50 |

| Perth | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Other facility(44) | 3 | 29 | 1 | 7 | 40 |

| Total | 44 | 748 | 163 | 21 | 976 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

Table 2: Children in immigration detention by method of arrival: 2000-2001

| Children in detention 2000-2001 | Overstayed visa | Boat arrival with no visa | Air arrival with no visa | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtin | 0 | 499 | 0 | 2 | 501 |

| Port Hedland | 8 | 330 | 12 | 1 | 351 |

| Woomera | 0 | 710 | 0 | 0 | 710 |

| Villawood | 69 | 27 | 35 | 33 | 164 |

| Maribyrnong | 9 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 28 |

| Perth | 2 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 17 |

| Other facility | 11 | 37 | 2 | 102(45) | 152 |

| Total | 99 | 1616 | 61 | 147 | 1923 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

Table 3: Children in immigration detention by method of arrival: 2001-2002

| Children in detention 2001-2002 | Overstayed visa | Boat arrival with no visa | Air arrival with no visa | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtin | 0 | 232 | 0 | 0 | 232 |

| Port Hedland | 0 | 220 | 5 | 0 | 225 |

| Woomera | 0 | 583 | 1 | 0 | 584 |

| Villawood | 72 | 22 | 19 | 27 | 140 |

| Maribyrnong | 10 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 38 |

| Perth | 0 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 18 |

| Other facility | 5 | 124(46) | 1 | 85(47) | 215 |

| Christmas | 0 | 238 | 0 | 0 | 238 |

| Cocos Keeling | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 87 | 1440 | 42 | 127 | 1696 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

Table 4: Children in immigration detention by method of arrival: 2002-2003

| Children in detention 2002-2003 | Overstayed visa | Boat arrival with no visa | Air arrival with no visa | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baxter | 0 | 69 | 1 | 5 | 75 |

| Curtin | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Port Hedland | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| Woomera | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| Villawood | 134 | 4 | 5 | 46 | 189 |

| Maribyrnong | 26 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 46 |

| Perth | 2 | 5 | 6 | 17 | 30 |

| Other facility | 14 | 29 | 1 | 248(48) | 292 |

| Christmas | 0 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 18 |

| Total | 176 | 180 | 20 | 327 | 703 |

Source: DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

As the above tables demonstrate, during the Inquiry period of 1999-2002, the vast majority of children taken into immigration detention were children arriving in Australia by boat without a visa. This report accordingly focuses on those children, although the Inquiry also interviewed other children during visits to detention centres.(49)

While the above tables demonstrate the total numbers in detention each year, the population of children in immigration detention centres varies from day to day. The following table gives a snapshot of the child detainee population on 1 January and 1 July from 1999 to 2003.

Table 5: Child detainee population, biannually by centre: July 1999 - July 2003

| Child detainees | 1.7.99 | 1.1.00 | 1.7.00 | 1.1.01 | 1.7.01 | 1.1.02 | 1.7.02 | 1.1.03 | 1.7.03 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtin | - | 147 | 133 | 167 | 153 | 63 | 33 | - | - |

| Port Hedland | 27 | 91 | 142 | 64 | 128 | 85 | 11 | 20 | 14 |

| Woomera | - | 118 | 215 | 16 | 304 | 281 | 45 | 11 | - |

| Woomera Housing Project | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| Villawood | 19 | 32 | 32 | 28 | 37 | 16 | 14 | 32 | 29 |

| Maribyrnong | 11 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 5 |

| Perth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Christmas Island | - | - | - | - | - | 79 | 10 | 5 | - |

| Cocos K. Islands | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | - |

| Baxter | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 38 | 41 |

| Other (hospitals, prisons, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 17 | 11 |

| Total | 58 | 399 | 542 | 287 | 631 | 543 | 138 | 132 | 111 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004; DIMIA, Email to Inquiry, 6 February 2004.

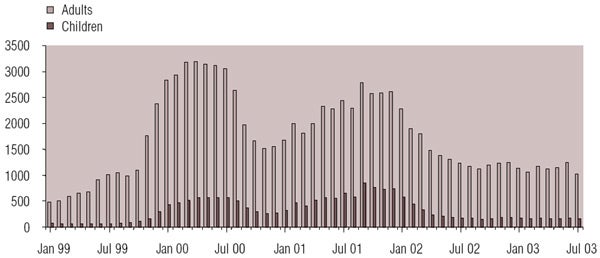

In order to give an indication of the proportion of detainees who were children, the following chart shows the total number of detainees for every month between January 1999 and 1 July 2003, broken down into adult and child populations.

Table 6: Number of children and adults in detention, 1 January 1999 to 31 July 2003

The number of children who arrived by boat increased in late 1999. From 1 January to 31 October 1999, 62 boats arrived in Australia, with an average of 1.8 children per boat.(50) Just one boat in the period carried more than 20 children.(51) More than half of the 62 boats had no children on board at all.(52) However, over the period 1 November to 31 December 1999, 24 boats arrived, with an average number of 13 children per boat. Over the year 2000, the average number of children per boat was

In 2001, the average number of children per boat - and percentage of children per boat - grew further. Of the 32 boats that arrived between 1 January and 22 August 2001, one carried 154 children, which was 45 per cent of its passengers. Over the year, the average number of children per boat was 30.(54) The last boat to arrive before the Tampa incident and the legislative changes that became known as the 'Pacific Solution' was at Christmas Island on 22 August 2001. It carried 95 children and 264 adults.

Since August 2001, most boats have been intercepted pursuant to the 'Pacific Solution' legislation. This included 11 boats in the remainder of 2001 and one in May 2002.(55) A further four boats were intercepted at sea and returned to Indonesia.(56)In July 2003 a boat carrying 53 Vietnamese citizens entered Australia's migration zone near Port Hedland in Western Australia. Its passengers were taken to Christmas Island for processing under the Migration Act. In November 2003, a boat carrying 14 Turkish citizens entered Australian waters but was returned to Indonesia.

While it is important to note that the number of child boat arrivals decreased to almost zero after August 2001, the numbers of detained asylum-seeker children decreased at a slower rate, since many children remained in detention for longer periods.

3.3 How many detainee children have been recognised as refugees?

The Minister has consistently stated that the Government does not detain refugees, because any asylum seeker who is found to be a refugee is immediately released. It is important to note in this regard that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) takes the view that a person is a refugee as soon as his or her circumstances fit the definition, rather than when they are formally recognised as such. On this view those asylum seekers who are eventually identified as refugees, and who are detained throughout that process, have in fact been detained while they are refugees.

In the period between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003, 3125 asylum-seeking children arrived in Australia with a valid visa, and therefore were not detained on arrival.(57)The top three countries of origin were Fiji, Indonesia and Sri Lanka.(58) Only 25.4 per cent of children arriving with a visa were found to be refugees.(59)

In the period between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003, 2184 children arrived in Australia without a valid visa and applied for asylum.(60) They were mainly from Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran.(61)All these children were detained on arrival in the Department's immigration detention centres and 92.8 per cent of them were eventually recognised as refugees.(62) For some nationalities the percentage was even higher (see below).

The success rate of asylum seekers in detention demonstrates that almost all children arriving in Australia without a visa are genuine refugees who eventually end up living in the Australian community. In fact, many more asylum-seeker children who arrive in Australia without a visa and apply for asylum from detention centres (unauthorised arrivals) are found to be refugees than children who arrive in Australia with a visa (authorised arrivals).(63)

Table 7: Child asylum seekers found to be refugees

| Year of application | Unauthorised arrival child asylum seekers recognised as refugees | Authorised arrival child asylum seekers recognised as refugees |

|---|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | 95.2% (569 out of 598 applicants) | 30.6% (260 out of 851 applicants) |

| 2000-2001 | 90.0% (815 out of 906 applicants) | 19.0% (185 out of 973 applicants) |

| 2001-2002 | 95.2% (639 out of 671 applicants) | 23.7% (178 out of 751 applicants) |

| 2002-2003 | 33.3% (3 out of 9 applicants) | 30.9% (170 out of 550 applicants) |

Source: DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004. The figures do not include protection visa applications awaiting a final outcome.

97.6 per cent of detained Iraqi children were found to be refugees andreleased from detention(64)

Nearly half of the unauthorised arrival children who applied for asylum from detention between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003 were from Iraq.(65) As at 31 December 2003, 1030 of the 1055 children had been granted a protection visa.(66) Most identified as being of 'Arab' or 'Iraqi' descent.(67)

We came here because there was a fight in our country, and now we are in a safe place we hope that we can stay here.

Primary school-aged Iraqi boy found to be a refugee(68)

In Iraq, children live under what is arguably the most diabolical political regime in the history of human civilisation. The entire population survives in a state of constant alert, always fearing and preparing for an impending war. There is not a single Iraqi child alive today who has not seen war or the devastating effects of the combination of Saddam Hussein's despotic rule and the UN's crippling sanctions.

Sabian Mandaean Association(69)

Many of the asylum-seeker children who came from Iran are actually the children of exiled Iraqis. Survivors of the 'SIEV-X' drowning tragedy said:

Iraq is like a prison, we escaped to Iran, we were oppressed in Iran, they would not even admit our children into schools in Iran. In May and June 2001, the real estate agents in Iran were officially ordered not to rent property to foreigners and employers were also told not to employ foreigners. This was an official order applicable against Iraqis and Afghans. We are forced to seek asylum, we want to see our children go to school just like other children.(70)

95 per cent of detained Afghan children were found to be refugees and released from detention(71)

37 per cent of unauthorised arrival children who applied for asylum between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003 from detention were from Afghanistan. As at 31 December 2003, 776 of the 817 children had been granted a protection visa.(72)

Of the detained Afghan children, 78.1 per cent were from the Hazara ethnic group,(73)which is a Shi'a Muslim minority in central Afghanistan.(74)

Hazara refugee children described their experiences in Afghanistan to the Inquiry staff:

In Afghanistan the Hazara people were in danger. The Taliban government announced this publicly, they said that 'Afghan people' have the right to stay in Afghanistan - that's the Pashtun peoples - Tajiks are going to Tajikistan, the Uzbeks are going to Uzbekistan, the Hazara people are going to the grave. And the Australian government was aware of us so why did they put us in detention centres?

Unaccompanied boy found to be a refugee(75)

The Taliban took my father and my older brother and my mother was very devastated by what had happened to us and she told me I had to leave. She thought that my cousin was going to leave and I could go with him and I had no idea of where we were going and what arrangements were made.

Unaccompanied teenage boy found to be a refugee(76)

The Taliban took two of my brothers and we do not know what has happened to them. And since then my father decided to save us as it was very difficult to lose any more of his family.

Teenage girl found to be a refugee(77)

74.2 per cent of detained Iranian children were found to be refugees andreleased from detention(78)

A further 9.5 per cent of unauthorised arrival children who applied for asylum between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003 from detention were from Iran. As at 31 December 2003, 155 of the 209 Iranian children had been granted a protection visa.(79)

At Curtin, an Iranian father told the Inquiry:

I didn't choose Australia for living. I didn't come to Australia for disco. I didn't come for a better life. My life and my family's life was in grave danger, that's why I had no choice but to leave my country. I was forced to leave my country.(80)

The Sabian Mandaean minority from Iran comprised approximately 27.2 per cent of the Iranian detainee population as at 31 January 2003.(81) The Australian Sabian Mandaean Association told the Inquiry that:

In Iran, the children are forced to study the Islamic religion knowing full well that it is not the faith of their parents. They are bullied incessantly by Muslim children. Muslim children pick on them for being Mandaean, calling them 'negis', which means defiled. They are not allowed to play with Muslim children and are ostracised in school playgrounds. Disputes and disagreements between children are almost always resolved in favour of the Muslim child. They are not allowed to drink from the water fountains utilised by Muslim children as they are told they would contaminate the water due to their Mandaeanism. A number of Mandaean children have been abducted by Islamists and forcibly converted to Islam. A larger number have been threatened with abduction and forced conversion. This is often, but not exclusively, used as a tool by corrupt authorities and criminals to extort money from well to do Mandaean jewellers. An even more serious occurrence is the sexual assault of Mandaean children. Even in these instances, Mandaeans have no recourse under Iran's Islamic laws and complaining only serves to exacerbate the situation for the Mandaean child and her parents.(82)

3.4 How long have children been in immigration detention?

Since 1999, children have been detained for increasingly longer periods. By the beginning of 2003, the average detention period for a child in an Australian immigration detention centre was one year, three months and 17 days.(83) As at 26 December 2003, the average length of detention had increased to one year, eight months and 11 days.(84)

Table 8: Length of detention of children over time

| Periods children detained | 0-6 weeks | 1.5-3 months | 3-6 months | 6-12 months | 12-24 months | 2-3 years | Longer than 3 years | Total children detained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Jan 99 | 26 | 23 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 59 |

| 1 Apr 99 | 19 | 9 | 16 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 54 |

| 1 July 99 | 19 | 5 | 15 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 58 |

| 1 Oct 99 | 37 | 29 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 98 |

| 1 Jan 00 | 220 | 128 | 27 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 399 |

| 1 Apr 00 | 72 | 110 | 299 | 22 | 18 | 0 | 2 | 523 |

| 1 July 00 | 51 | 51 | 169 | 252 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 542 |

| 1 Oct 00 | 94 | 9 | 34 | 138 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 293 |

| 1 Jan 01 | 122 | 48 | 55 | 24 | 33 | 5 | 0 | 287 |

| 1 Apr 01 | 212 | 107 | 87 | 47 | 30 | 3 | 0 | 486 |

| 1 July 01 | 174 | 170 | 184 | 71 | 29 | 3 | 0 | 631 |

| 1 Oct 01 | 193 | 242 | 153 | 108 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 740 |

| 1 Jan 02 | 5 | 87 | 288 | 104 | 52 | 7 | 0 | 543 |

| 1 Apr 02 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 98 | 69 | 10 | 0 | 202 |

| 1 July 02 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 33 | 85 | 7 | 0 | 138 |

| 1 Oct 02 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 79 | 19 | 0 | 134 |

| 1 Jan 03 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 56 | 36 | 3 | 132 |

| 1 Apr 03 | 17 | 3 | 14 | 9 | 33 | 49 | 0 | 125 |

| 1 July 03 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 69 | 1 | 111 |

| 1 Oct 03 | 12 | 24 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 54 | 8 | 121 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

While many children are released within three months of being taken into detention, there have always been a number of children detained for longer periods of time. The Inquiry is concerned about the deprivation of liberty of any child for any period; however the large numbers of children in detention for longer periods are of particular concern.

Children were generally detained in remote centres for longer periods of time than in city centres. This is most likely because more of the children in metropolitan centres were overstayers rather than asylum seekers. At Curtin over 1999-2000, 84 per cent of the 200 children had been detained for longer than three months, and at Port Hedland, 78 per cent of the 286 children had been detained for longer than three months. In the same period, 99 per cent of 248 children at Woomera had been detained for longer than three months. This is in contrast with the children at Villawood and Maribyrnong, the majority of whom were detained for less than six weeks.(85)

At Curtin over 2000-2001, 69 per cent of the 501 children had been detained for longer than three months, including 63 children who had been detained for over a year. At Port Hedland, 74 per cent of the 351 children had been detained for longer than three months, including 38 who had been detained for over a year. In Woomera 78 per cent of the 710 children were detained for longer than three months, including 44 children from more than a year. By contrast, most children were detained at city facilities for less than six weeks.(86)

On 1 July 2000, 440 children (81 per cent) had spent more than three months in detention. By April 2001, although most child detainees had not spent more than three months in detention, 80 children (16 per cent) had been in detention for more than six months, and by 1 October 2001, that figure had increased to 152 (21 per cent).

Over 2001-2002, 77 per cent of the 232 children at Curtin, 94 per cent of the 225 children at Port Hedland and 94 per cent of the 584 children at Woomera had been detained for over three months. The majority of children at Maribyrnong, Perth and Villawood were detained for under six weeks. At Christmas Island, the majority of children were detained for between one and a half and three months.(87)

On 1 January 2002, 59 children (11 per cent) had spent more than a year in detention. By 1 January 2003, of 132 child detainees, 95 children (72 per cent) had been detained for more than a year; 36 of these children had been in detention for over two years and three had been in detention for over three years.

Over 2002-2003, 93 per cent of the 40 children at Curtin, 100 per cent of the 24 children at Port Hedland and 85 per cent of the 72 children at Woomera had been detained for over three months. The majority of children at Maribyrnong, Perth and Villawood were detained for under six weeks. However, 28 per cent of the 158 children at Villawood had been detained for more than 6 months and 13 per cent had been detained for more than a year.(88)

On 1 October 2003, only 30 per cent of the 121 child detainees had been detained for less than three months. 57 per cent had been detained for more than one year, 51 per cent had been detained for over two years and 7 per cent had been detained for more than three years.

The longest a child has ever been in immigration detention as at 1 January 2004, is five years, five months and 20 days. This child and his mother were released from Port Hedland detention centre on 12 May 2000.(89)

3.5 What is the background of children in immigration detention?

3.5.1 How many children come without their parents?

So, you've heard about Moses, you know, the prophet? His mother left him alone in the small box in the water. So I am asking, did his mother not love him? Does his mother not love him to leave him alone in the small box? No of course not - no mother does not love her child. If he was still with her he would get killed from that time. So, also we have the same conditions in our families. So, we left our families.

Unaccompanied boy found to be a refugee(90)

Most asylum-seeking children arriving in Australia without a valid visa come with their parents. However, there are significant numbers of unaccompanied children.

Table 9: Unaccompanied vs accompanied unauthorised arrival children who applied for a protection visa: 1999-2002

| Year | Unaccompanied children | Accompanied children |

|---|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | 64 | 617 |

| 2000-2001 | 170 | 844 |

| 2001-2002 | 51 | 451 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

Of the child asylum seekers who arrived in Australia without a valid visa between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2003, approximately 14 per cent were unaccompanied children.(91) On average, 91.2 per cent of unaccompanied children in detention were found to be refugees.

Table 10: Unaccompanied detainee children found to be refugees

| Year of application | Percentage of unaccompanied children in detention found to be refugees |

|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | 96.7% (59 out of 61) |

| 2000-2001 | 89.9% (124 out of 138) |

| 2001-2002 | 89.8% (88 out of 98) |

| 2002-2003 | (0 out of 0) |

Source: DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

54.5 per cent of the unaccompanied children arriving without a valid visa in Australiabetween 1 January 1999 and 30 June 2002 were 16 to 17-years-old, with 39 per cent in the 13 to 15-year-old age bracket and 6.5 per cent aged under 13.(92)

The vast majority (86.7 per cent) of unaccompanied children came from Afghanistan. The remainder were Iraqi (10.5 per cent) and Iranian (1 per cent). There was one unaccompanied child from each of the following countries: Pakistan, Palestine, Sri Lanka, Syria and Turkey. There were only four girls (two Iraqi and two Afghan).(93)

The following table provides a snapshot of the numbers of unaccompanied children in detention from 1999-2003.

Table 11: Biannual snapshot of numbers of unaccompanied children in detention: 1999-2003

| Date | Unaccompanied children detained | Total children detained |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Jan 1999 | 1 | 59 |

| 1 July 1999 | 2 | 58 |

| 1 Jan 2000 | 41 | 399 |

| 1 July 2000 | 49 | 542 |

| 1 Jan 2001 | 37 | 287 |

| 1 July 2001 | 121 | 631 |

| 1 Jan 2002 | 40 | 543 |

| 1 July 2002 | 12 | 138 |

| 1 Jan 2003 | 8 | 132 |

| 1 July 2003 | 8 | 111 |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

From the above table, it is clear that from the outset of 2000 there was an exponential rise in the number of unaccompanied children detained in Australia. This rise was commensurate with the increase of adults and families being detained over the same period.

On 1 July 1999 there were just two detained unaccompanied children, who had been detained for fewer than three months. Six months later, that figure had grown to 41. By 1 July 2000 there were 49 unaccompanied children in detention, 37 of whom had been detained for longer than three months. A year later, there were 121 unaccompanied children in detention, 22 of whom had been detained for over three months.(94) Their number grew to 143 during July 2001.(95)

At 1 January 2002, there were only 40 unaccompanied children in detention, but 90 per cent of them had been detained for longer than three months.(96) By 12 April 2002, 13 out of 21 unaccompanied children were living in foster care detention in the community.(97) By 2 December 2002, there were 17 unaccompanied children in detention, 12 in foster care detention and five in a detention centre (four in Villawood and one in Woomera).(98) By April 2003, there were just two unaccompanied child asylum seekers left in detention centres, one of whom had been in detention since 31 December 2000. As at 28 November 2003, there were five unaccompanied children in detention centres but by 26 December 2003 all unaccompanied children in immigration detention were either in foster care or in a private apartment as alternative places of detention.(99)

The numbers of unaccompanied children in detention may have decreased over 2002 due to a combination of the processing and granting of visas, the fact that some children may have turned 18 and hence been declassified as 'unaccompanied children' and because no more boats were permitted to enter and/or remain in Australian waters.

3.5.2 How old are the children?

The following table sets out the total number of children in detention as at 30 June from 1999 to 2003, sorted into age groups. It provides the average length of time that children in each of these groups had spent in the remote detention facilities. It also sets out the maximum period of time any child in each age group had spent in any detention facility.

Table 12: Age and average length of detention of children, 1999-2003

| Age of children as at 30 June | Total number of children in detention | Av. time in detention for children in Woomera | Av. time in detention for children in Curtin | Av. time in detention for children in Port Hedland | Av. time in detention for children in Baxter | Max. time in detention of any child in any detention facility |

| 30 June 1999 | ||||||

| 0-4 yrs | 23 | - | - | 245 days | - | 1084 days |

| 5-11 yrs | 15 | - | - | 337 days | - | 1681 days |

| 12-17 yrs | 23 | - | - | 46 days | - | 257 days |

| 30 June 2000 | ||||||

| 0-4 yrs | 164 | 157 days | 160 days | 129 days | - | 665 days |

| 5-11 yrs | 208 | 173 days | 173 days | 140 days | - | 675 days |

| 12-17 yrs | 162 | 170 days | 157 days | 132 days | - | 623 days |

| 30 June 2001 | ||||||

| 0-4 yrs | 144 | 66 days | 143 days | 105 days | - | 1030 days |

| 5-11 yrs | 210 | 50 days | 221 days | 135 days | - | 1030 days |

| 12-17 yrs | 278 | 69 days | 128 days | 147 days | - | 600 days |

| 30 June 2002 | ||||||

| 0-4 yrs | 33 | 479 days | 580 days | 590 days | - | 605 days |

| 5-11 yrs | 54 | 468 days | 579 days | 659 days | - | 918 days |

| 12-17 yrs | 53 | 467 days | 637 days | 665 days | - | 965 days |

| 30 June 2003 | ||||||

| 0-4 yrs | 32 | 680 days* | - | 566 days | 409 days | 970 days |

| 5-11 yrs | 29 | 831 days* | - | 1003 days | 844 days | 1040 days |

| 12-17 yrs | 52 | 845 days* | - | 1010 days | 830 days | 1104 days |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 3 March 2003, Attachment B; DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003,Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

*Children in Woomera on 30 June 2003 were detained at the Woomera RHP.

3.5.3 How many infants are in detention?

As can be seen from the above table, some infants (0-4 years) have spent substantial portions of their lives in immigration detention. For instance, on 30 June 1999, an infant had spent nearly three years in Port Hedland detention centre.(100) On 30 June 2000 there were 164 infants in detention.(101) Five of them had spent more than 18 months in detention.(102) On 30 June 2001 there were 144 infants in detention.(103) Two of these children had spent more than two and a half years in detention - more than half of their lives.(104)

Of the infants in detention, 95 per cent who applied for protection visas in 19992000 were eventually determined to be refugees. The following year, 94 per cent were recognised as refugees and in 2001-2002, 95 per cent were found to be refugees.(105)

From 1 January 1999 to 26 December 2003, 71 babies were born in detention to unauthorised boat arrival mothers.(106) A mother of children too young to be interviewed said:

It is sad that my baby was born in a prison. It is sad that I tried to give them a better life by coming here but in doing so I feel that I have made their lives worse. The children are worse off because of the things they have seen in here such as the guards beating people up, they have nightmare. I am not sure if the children will ever be able to forget what they have seen, once they leave.(107)

A paediatrician who examined a three-year-old Woomera detainee told the ACM Woomera Medical Officer:

I would further point out that this young man has been in detention for 20 months, this is a long time in adult terms but is a very long time in terms of this young man's age of 3 3/4 being some 40 per cent of his life. The ideal environment for this young man to settle would be a family home setting with appropriate social and other supports.(108)

On 1 April 2003, there were 38 infants in immigration detention centres: 11 had been in detention for more than a year, and three had been in detention for more than two years.(109) As at 26 December 2003, there were 29 infants in immigration detention: 13 had been in detention for more than a year, five had been in detention for more than two years and two had been there for more than three years.(110)

3.5.4 Are there more boys than girls?

There are more boys than girls in immigration detention, although the percentage of girls has increased since 1999.(111) Overall, for the period 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2003, 37 per cent of unauthorised arrival child asylum seekers were girls.(112) In 1999-2000, 31.4 per cent of unauthorised arrival child asylum seekers were girls; that figure increased to 43.8 per cent in 2002-03.(113)

3.5.5 Which countries do the children come from?

The majority of children among 'boat people' in the late 1980s and early 1990s were from Cambodia, China and Vietnam. More recently, asylum-seeker children arriving in Australia without a visa have come from Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, the Palestinian Territories and Sri Lanka.(114)

Table 13: Nationality of unauthorised arrival children seeking asylum from detention, by year of application

| Nationality | 1999-2000 | 2000-2001 | 2001-2002 | 2002-2003 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 326 | 297 | 433 | 2 | 1058 |

| Afghanistan | 189 | 481 | 150 | 0 | 820 |

| Iran | 37 | 89 | 78 | 7 | 211 |

| Palestine | 2 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 31 |

| Stateless | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Sri Lanka | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Turkey | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Syria | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Algeria | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Egypt | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Other | 18 | 14 | 3 | 6 | 41 |

| Total | 602 | 918 | 677 | 16 | 2213 |

Source: DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

Most of the children are Shi'a Muslim. Most speak Iranian languages or Arabic. The following table shows the languages, religions and ethnic groups of children in detention.(115)

Table 14: Children in detention 1999-2002: languages, religions and ethnicities

| Nationality | Language | Religion | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | Arabic | Shi'a and Sunni Muslims; Chaldean and Assyrian Christians; Sabian Mandaean | Arab; Kurdish; Armenian; Iranian; Palestinian; Turkman |

| Afghanistan | Dari (Afghan Persian); Hazaragi; Pashto; Uzbek | Shi'a and Sunni Muslim | Hazara; Tajik; Uzbek; Arab; Pashtun; Persian |

| Iran | Farsi (Modern Persian) | Shi'a Muslim; Sabian Mandaean; Zoroastrian | Persian; Arab; Armenian; Iraqi; Azerbaijani; Kurdish |

| Palestine | Arabic | Sunni Muslim | Arab; Palestinian |

| Sri Lanka | Tamil | Hindu | Tamil |

| Turkey | Turkish, Kurdish | Sunni Muslim | Kurdish |

Source: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 29 November 2002, Attachment, pp2-8, supplemented by Inquiry research.

3.6 How did the children get to the detention centres?

We came by boat and we were in the boat for ten days. It was very hot, horrible. We were in a small boat. I was saying, 'Dad, when are we changing our boat? We can't relax here; it is more dangerous than our country! We will drown!' And he was saying, 'don't worry, we will go to another boat, to a bigger boat' and he was just giving me hopes.

But it wasn't true; we stayed in the same very small boat. We were just going and we didn't have any food or drinks and you had just to vomit. And I said, 'When are we reaching it?' and he said, 'This is the boat we are going on!', because he got angry, I was just keeping asking. We were all down below, and it was very hot, you know, near the machine of the boat.

In the boat there were many different people from our country, they were Hazara but we didn't know them. Most of them were Hazara people, except one. He was Iranian. For my Mum, it was really, really difficult ... there wasn't any drink, and the seawater was coming on her and she was wet. She was so sick and we couldn't do anything.

Afghan teenage girl found to be a refugee(116)

Drawing of a boat of children seeking asylum in Australia, by a child in immigration detention.

After a long trip from their home countries, asylum-seeker children typically come to Australia by boat from Indonesia. The boats are often not seaworthy and the trip usually takes several days in extremely crowded conditions, with limited food and water. For the most part, children arriving by boat land in northern Australia, at Ashmore Islands, Ashmore Reef or Christmas Island.(117)

The Ashmore Islands and Ashmore Reef are in the Indian Ocean, on the outer edge of the continental shelf. They are approximately 320 km off Australia's north-west coast, 170 km south of Roti Island (Timor) and 610 km north of Broome in Western Australia. Christmas Island is also in the Indian Ocean, 2300 km north-west of Perth, and is closer to Java than Australia, by 1040 km.(118)

Refugee children told the Inquiry about their first impressions of arriving in Australian waters: When we arrived, they just announced, 'You're in Australian water, don't go anywhere!' and also there were some people who knew English on our boat and when they came in they were like lots of soldiers, they were looking like commandoes or something. And big, big guys said, 'Okay, who knows English here?' and half of the ship knew English, especially me, and I was scared they might throw me out or something and I go like 'mmmm'. There was no one to speak English and there was an old man, he just said [intentionally faltering], 'I am leetle bit good' and they just asked him 'where did you come from?' and then we stayed for one night in the water and then they just took us: 'Welcome!'

Unaccompanied Afghan boy found to be a refugee(119)

[W]e wanted help and we thought Australian ship was going to come and we would shout and scream that we need help. And they came to us and they said no, they can't do anything, they would fix it a little bit but we have to go back to Indonesia. So in that condition they were trying to send us back. And there were women pregnant and we were showing them they were pregnant and they were shouting that we had to go back. Those people were shouting and they were showing their hands like they wanted to hit us and saying, 'You have to go back' ... The Australian boat came again and said, 'Why don't you go back?' and we said, 'Our boat has a hole'. All of us were crying, all the small children and the women. And the men were crying. They put our food in the sea as the boat had a hole and we had to make it lighter and so we did that. And after one day the Australian boat came again and everything was going around our ship. (Aeroplanes?) Yes. We were shaking our hands and waving to show them we were needing help but they didn't do anything. After one day they came again and finally all the women, the children and the men were crying that we really needed help and they said, 'Okay, we are going to get you to Australia'.

Teenage girl found to be a refugee(120)

We arrived at Christmas Island but of course when we arrived the Australian boat came and said 'don't move, stay there', so they came and checked. They asked to move and got us on to their boats and then they took us to the island. They took us to a hall and there were 150 of us and two hours later they brought us some food.

Teenage unaccompanied boy found to be a refugee(121)

The children were not taken to detention centres immediately:

When we arrived the officers took us by bus to Darwin and then the interview started.(122) There was no interpreter for us. People who couldn't speak, they just ...they asked our names and whoever could answer it, they answered them. And then they said 'you are here illegally so you will be detained' and then after they took us to the camp ...When we arrived [at the detention centre] they give us just one piece of sandwich until the next morning. After 6 hours [we got] meat, rice, I think, I forgot. No drink, nothing else, no fruits.

Teenage unaccompanied boy found to be a refugee(123)

When we arrived in Australian waters, we were all happy. When I saw the aeroplane, I was shouting in my language to ask for help, because I didn't even have the least bit of English. My Dad said 'they don't understand you'. I said however 'I am shouting and screaming, they will help me'. Another woman was there and she knew English and she said, 'help!' And I said 'what the hell are you talking about, "help, help, help"'? [laughs]. I was going to tell her to say 'help' in our language but she said they don't understand it, so I said, okay.

Then the aeroplane just circled and he went and left us and then the navy ship came. We were all screaming and crying and they said 'you have to go back' and they tried to send us back. There was a man, he knew English very well, and he showed them my Mum, and explained she was very sick and the children. But they were still saying, 'we are not allowed to let you come to Australia, you have to go back'.

After that, the women didn't know anything, they were just crying, they were trying to say, 'we need help'. And finally they took our names and they took us to Darwin and we stayed for one night. They gave us food. It wasn't good food, it was a sandwich, but it wasn't like really very good.

We stayed there for one night and after that they sent us to the detention centre, to Curtin, by plane from Darwin.

Teenage girl found to be a refugee(124)

3.7 What did children and their parents say about detention centres?

In Queensland, the Youth Advocacy Centre and Queensland Program of Assistance to Survivors of Torture and Trauma interviewed former detainee children for their submission to the Inquiry. One of the questions they asked children was to give one word to describe the detention centre. One child said, 'prison' and another said 'a grave'.(125)

Children and young people also told the Inquiry that detention made them feel like they were in a prison:

I have very bad impressions from the detention centre. When I was in detention centre I really did not think that it is going on and you know, I understood, I was like animal in detention centre, and because ... Australian police they captured us and they put in prison. This is not like a detention centre, I can't say it's a detention centre, it's prison, it's gaol, and no one has freedom and we cannot go outside and we cannot do things. And also there it is very hot. If you go outside the sun will burn, and there's many insects, reptiles and if you go outside, the insects bite us. Reptiles, I saw many reptiles around ... we couldn't tell any things to officers or other people because we were afraid of them because maybe if we say something, something might happen.

Unaccompanied Afghan boy found to be a refugee(126)

Some children thought that detention was worse than they imagined prison might be, particularly because of the uncertainty as to when they would be released:

I know what most of the people don't know about the detention centre, like how it is, but I think every Australian knows what a prison is, what a prison looks like and what happens in a prison. All the people, even in prison, like the prisoners they know when they're gonna be released, when they're sentenced they know that for this long they're in prison and at that date they're gonna get their freedom.

So even they know, like for six months, for ten years or for twenty years so they are there and after that they're gonna get their freedom. But in detention centre, like no one knows when they're gonna be released. Tomorrow, day after tomorrow, for two years like, you know, waiting how much hard it is, only if it is only 15 minutes [and] they're under 18, they've been there for two years, [those] who came before us, they're still there. So just imagine how they would be.

Teenage boy found to be a refugee(127)

I can tell you that things are very, very difficult for us. I can say that you can never call that place a detention centre. It was of course a prison and a gaol. Even in prison you know at least for how long you will be in prison, but in a situation like that we did not know what was happening next. We did not know how long we would be spending in this place. And most of the time our roommates and the people who used to live with us, they were getting changed every three weeks or every two weeks, the people that we were getting around for a while they used to go and then some new people would replace them. And sometimes they would put the new arrivals with the people who have been there for a quite a long time who have completely lost their minds and their ability to think and when you spend some time with people like that who have been out of their minds so of course you lose your mentality, and you lose your thoughts as well and this is what was happening to us. Sometimes I was looking at those people I was thinking that we'll all end up in the same place so in short, I can say life was very horrible.

Unaccompanied Afghan boy found to be a refugee(128)

Several children likened themselves to birds in a cage.

I am like a bird in a cage. My friends who went to other countries are free. [One of his drawings was of an egg with a boot hovering above it ready to crush it. Pointing to the egg he said,] These are the babies in detention centres.

16-year-old detainee who had spent three birthdays in detention(129)

I think that the children should be free and when they are there for one year or two years they are just wasting their time, they could go to school and they could learn something. They could be free. Instead they are like a bird in a cage.

10-year-old Afghan girl found to be a refugee(130)

A teenager who had been detained at several different detention centres said of Woomera:

It's really a hell hole, the worst one of all. [Why?] I've never seen anything that's the same as that in my life. I've been in the gaol, the gaol is better than Woomera.

Detainee boy(131)

At the new Baxter detention centre at Port Augusta, the Inquiry heard:

The officers tell me how good it is here because we have two toilets, two showers. But [my son] says 'we don't need that, we need stimulation. We need that more than water'.

Detainee mother, Baxter(132)

We came here because we wanted freedom. We did not come to be imprisoned for three years. Nothing will help us, only freedom will help us. We want to be free that is all.

Detainee boy, Baxter(133)

An Afghan father in detention asked the Human Rights Commissioner the following questions about the future of children in detention:

I have a request. What will happen with the future of these children, that they see in front of them people cutting themselves and hanging themselves? What is the effect on their minds? What can they get? They are the future ...We do not want anything. We did not come here for a visa. [We would be happy] if we could be let out in some poor third world country. Just send my children to school and let them be in freedom. They should live in a human good atmosphere, they should learn something good, and not the things they are learning here.(134)

Many children were at pains to explain that they were not criminals:

They should keep us out of detention because the children have nothing, they are not criminals, they are just born, they want to be free, they are like birds. If we keep birds like this, we are the same ... We want to be one hand of Australia, like shoulder by shoulder, but I don't know what Mr Philip Ruddock thinks, he thinks we are criminals, it is impossible - how can we be criminals? We are just new, new generation. We have seen war a lot.

Unaccompanied Afghan asylum seeker teenage boy in home-based detention(135)

One boy said that he tried to hide his past from his new friends because he felt that his detention branded him as a criminal:

While I was in detention centre there was a lot of violence and I was treated like a criminal. The impact that I got out, when I got out of the detention centre, I still feel that I'm a criminal in Australia ... I was in detention centre about seven months while I haven't done anything, so now, when I got out I got friends but I'm by myself. They asked me, 'where are you from?' I say I'm from Spain because I can't face to say that I'm from Afghanistan because now the media is there ... now everybody knows about detention centres. Everybody, if you come from Afghanistan, if you say 'I'm from Afghanistan' then it's true that you are the person in detention centre and the way the media should ask, like, wants to come in Australia, like in search of food or like, they maybe, they want to come here to make a good life. But why should we, when we have got a country, if there is, if there is peace why should we flee our country? I mean, let's ask you a question, 'if in Australia now, do you want to go in any country?' In any other country like, you've got the working here. Of course not, you've been living here, you know everything about. The thing is our country, the problem is that there is no rule, no law, everybody kills each other, so we have come here to just to seek asylum. Of course to live as a human but now, I still have [the feeling that] I'm a criminal although I haven't done anything.

Teenage boy found to be a refugee(136)

Other children also felt Australians lacked compassion or empathy for them:

They say that the people will laugh at you and make fun of you. They are going to hate you. That's why we don't give you a visa.

Unaccompanied Afghan girls and boys found to be refugees(137)

It's just that I know that I have lots and lots of negative and better stories, I cannot finish all of them, it's just that I remember in Afghanistan when I was studying as a child, our teacher used to say that people of Australia were the most human and caring and loving people among the world and I was always thinking that they were, then as soon as I came to Australia in government detention centre my idea was completely changed. I found quite the opposite and I was just thinking if I had stayed in Afghanistan of course they would have killed me maybe in an hour or two but I ended up in here so physically they are keeping me alive but emotionally and spiritually they are killing me.

Afghan unaccompanied boy found to be a refugee(138)

I am not sure how people who are out of detention could sense or feel the situation of a person who has been in detention. It is that bad.

Unaccompanied teenage boy found to be a refugee(139)

Endnotes

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- 'Nominal capacity' refers to the Department's preferred capacity for operational purposes. It does not mean the number of beds available. DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 19 May 2003. The figure of 1160 for nominal capacity was provided in DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, Email to Inquiry, 12 January 2004.

- Inquiry, Notes from visit, Baxter, December 2002.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 16 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 17 December 2003.

- Derby is the main port for the Kimberley region. It is a regional administrative and supply centre with 5000 permanent residents.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Border Protection, Detention Centres - Perth Immigration Detention Centre, at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/borders/centres/ perth_irpc.htm, viewed 10 July 2003.

- The Department has advised the Inquiry that 'the nominal capacity of Port Hedland IRPC is 820 without J Block'. DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 19 May 2003.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 17 December 2003.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Detention Centres: Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre, at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/borders/centres/ woomera_irpc.htm, viewed 24 November 2003 and Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Last Detainees Leave Woomera For Baxter, Media Release, Parliament House, Canberra, 18 April 2003.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F. From early 2001 Woomera's nominal capacity increased to 2000. DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 19 May 2003.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Expansion of the Woomera Residential Housing Project, Media Release, Parliament House, Canberra, 9 May 2003.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- Minister for Immigration and Indigenous and Multicultural Affairs, Border Protection, Detention Centres, Woomera Residential Housing Project, at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/borders/centres/ woomera_rhp.htm#capacity, viewed 10 July 2003.

- Minister for Immigration and Indigenous and Multicultural Affairs, Border Protection: Detention Centres: Woomera Residential Housing Project, at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/borders/centres/ woomera_rhp.htm#capacity, viewed 24 November 2003.

- See Chapter 6 on Australia's Detention Policy for a comprehensive analysis of the Woomera RHP.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Another Detention Centre Mothballed, Media Release, Parliament House, Canberra, 19 March 2003.

- The Department asked the Inquiry to refer to the Pacific Solution detention centres as 'offshore processing centres' and to the detainees there as 'residents'. DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 19 May 2003.

- Migration Act 1958, (Cth), s5.

- See Chapter 6 on Australia's Detention Policy for further information.

- Question 1210 (1), (2), Commonwealth House of Representatives Hansard, 5 February 2003, pp11062-3.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 16 January 2004.

- According to DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a, Boat Arrival Details, at http://www.immi.gov.au/facts/ 74a_boatarrivals.htm, viewed 13,540 persons had arrived by boat without a visa between 1989 and April 2003. A further 53 persons arrived by boat (including 15 children) in July 2003, see Item 261 in Fact Sheet 74a.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004. The statistics provided include all instances of detention. Some children may be counted more than once due to transfers between detention facilities.

- Children who arrived by boat: 1999-2000: 76.6 per cent; 2000-2001: 84 per cent; 2001-2002: 84.9 per cent; 2002-2003: 25.6 per cent. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 30 January 2004. This figure does not include protection visa applications awaiting a final outcome.

- Please note that the Department has not provided any statistics regarding the detainee population in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. See further Chapter 2 on Methodology.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- On 1 December 2001 there were 714 children in immigration detention: DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 24 December 2002, Attachment F.

- DIMIA, Transcript of Evidence, Sydney, 2 December 2002, p3.

- Question 1404(1), Commonwealth Senate Hansard, 16 June 2003, p11583.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 16 January 2004.

- Data includes all instances of detention in the period - some children may be counted more than once due to transfers between detention facilities. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- This category refers to all unauthorised child boat arrivals and offshore boat arrivals.

- 'Other' includes the following categories: Deserter; Fisherman; Smuggler; Stowaway; and children who breached the conditions of various categories of visa. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003.

- 'Other facility' includes police watch houses, adult gaols and court police lockups in the ACT, NT, QLD, VIC and WA. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- Of the 102 children detained in 'other facilities' in 2000-2001, 35 were detained at Willie Creek Holding Centre north of Broome, WA. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- Most of these children were in transit in Western Australia. However, 35 of them were in hospital, including 10 at Woomera Hospital. 14 children were in foster care and a further six living in private apartments under ACM guard. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- These children were mainly detained in state gaols and police lockups. One child was housed in Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre in WA. 60 per cent of these children were detained in the 'Northern Territory Harbour', presumably on their fishing vessels. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- Data includes all instances of detention in the period - some children may be counted more than once due to multiple transfers between administrative holding facilities.

- Visa overstayer children in detention: 1999-2000: 4.5 per cent of child detainees; 2000-2001: 5.1 per cent of children detainees; 2001-2002: 5.1 per cent of child detainees. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- In 1998 there were 17 boats, of which only four carried children. There was an average of fewer than 10 boats per year for the previous decade. DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a, Boat Arrival Details, at http://www.immi.gov.au/facts/74a_boatarrivals.htm, viewed 10 July 2003.

- A boat which arrived at the Ashmore Islands on 11 October 1999 carried 21 children, plus one infant. DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a.

- 37 out of 62 boats carried no children. DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a.

- DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a.

- DIMIA, Fact Sheet 74a.

- DIMIA, Fact Sheet 76, Offshore Processing Arrangements, at http://www.immi.gov.au/facts/ 76offshore.htm, viewed 10 July 2003. Their passengers would have been transferred to Nauru or Manus Island, either directly or via Christmas Island.

- DIMIA, Fact Sheet 76.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- Fiji (356 child applicants); Indonesia (266); Sri Lanka (206). These were followed by Korea (160); Iraq (150) and India (129). DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 26 June 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- Iraq (1058 child applicants), Afghanistan (820), Iran (211). DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- This figure does not include protection visa applications awaiting a final outcome. DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004. Protection visas were granted to 2020 unauthorised arrival children who applied between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2002. Only 71 of these children received a permanent visa. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- Of the 2819 children granted refugee status over the period 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2003, 2026 children (71.9 per cent) were unauthorised arrivals and therefore had applied from detention, not the community. DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004; DIMIA Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 16 January 2004.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Perth, June 2002.

- Sabian Mandaean Association, Transcript of Evidence, Sydney, 17 July 2002, p67.

- Person 14, SIEV X Survivor Accounts, at http://www.sievx.com/articles/disaster/KeysarTradTranscript. html, viewed 10 July 2003.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- See Dr W Maley, 'Hazara and why they come here: Australia's New Afghan Refugees: Context and Challenges' at http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/html/resources/agmAfghan.html.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- NSW Commission for Children and Young People Submission 258, p14.

- NSW Commission for Children and Young People Submission 258, p14.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Inquiry, Interview with detainee family, Curtin, June 2002.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Sabian Mandaean Association, Transcript of Evidence, Sydney, 17 July 2002, pp66-67.

- Question 1210 (4), Commonwealth House of Representatives Hansard, 5 February 2003, pp11062-3.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004. The exact figure provided is 619 days.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 17 July 2003, Attachment B.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 17 July 2003, Attachment B.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 17 July 2003, Attachment B.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Question 1210 (3), Commonwealth House of Representatives Hansard, 5 February 2003, pp11062-3.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 30 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 29 November 2002, Attachment; DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 13 December 2002, Attachment A.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 29 November 2002, Attachment; DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA Submission 185, p191. Three more unaccompanied children were moved from Curtin on 23 April 2002 to foster care in Adelaide.

- DIMIA, Transcript of Evidence, Sydney, 2 December 2002, p3.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 12 December 2003; DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 3 March 2003, Attachment B.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 3 March 2003, Attachment B.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 30 May 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Confidential Submission 110, p41.

- Paediatrician, Port Augusta Hospital, Letter to ACM Woomera Medical Officer, 2 August 2002, copied to DIMIA Woomera Manager, (N5, Case 22, p145).

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 26 June 2003.

- DIMIA, Response to Second Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Protection visa applications of unauthorised arrivals, percentage of girls: 1999-2000: 33 per cent; 2000-2001: 37 per cent; 2001-2002: 42 per cent. DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 26 June 2003, Attachment.

- DIMIA, Letter to Inquiry, 26 June 2003, Attachment; DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 27 January 2004.

- Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Media Centre, 'Background Paper on Unauthorised Arrivals'.

- These languages, religions and ethnic groups may not necessarily reflect the languages, religions and ethnic groups of the children's countries of origin or of asylum seekers generally. The table is about detained asylum-seeker children in Australia.

- Inquiry, Confidential interview with a former detainee, Sydney, March 2003.

- Between 1 July 1999 and 22 August 2001, 135 boats arrived, 98 of which carried children on board. See DIMIA Fact Sheet 74a.

- Geoscience Australia, at http://www.ga.gov.au/, viewed 10 July 2003.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- NSW Commission for Children and Young People, Submission 258, p17.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- The child is not referring to an entry interview, but rather, basic information gathering. According to the Department, the scenario describes the stage at which Australian officials would still be making early assessments of any urgent medical cases and the overall basic needs of the group. DIMIA, Response to Draft Report, 19 May 2003.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- Inquiry, Confidential interview with former detainee, Sydney, 2003.

- YAC and QPASST, Submission 84, p5.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Brisbane, August 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- Uniting Church in Australia, Submission 151, p12.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Perth, June 2002.

- Inquiry, Interview with detainee, Villawood, August 2002.

- Inquiry, Interview with detainee, Baxter, December 2002.

- Inquiry, Interview with detainee, Baxter, December 2002.

- Inquiry, Interview with detainee, Woomera, June 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Adelaide, July 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Brisbane, August 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Perth, June 2002.

- Inquiry, Focus group, Melbourne, May 2002.

- NSW Commission for Children and Young People, Submission 258, p78.

13 May 2004