4 An overview of the children in detention

- 4.1 Nationalities of the children in detention

- 4.2 Reasons for seeking asylum

- 4.3 Age of children in detention

- 4.4 Unaccompanied children

- 4.5 When did the children arrive in Australia?

- 4.6 How long are children kept in detention?

- 4.7 Movement of children across the detention network

- 4.8 Mental health and wellbeing of children in detention

- 4.9 Detention is a dangerous place

- 4.10 Rates of self-harm amongst children

- 4.11 Mental health of parents

- 4.12 Children with disabilities

- 4.13 Children’s views about detention

- 4.14 The right to identity

- 4.15 Inquiry findings relevant to all children in detention and to children held on Christmas Island

My country and my religion is a target for Taliban. There were many bomb blasts and always big wars and terrible attacks. Shia people have arms, legs, noses hacked off, necks slashed, plus there is rocket fire and missiles. This is because I am Shia. All this means no one is safe and now because I escaped. I am in detention.[32]

(Unaccompanied child, Nauru Regional Processing Centre, May 2014)

Drawing by primary school aged child, Christmas Island, 2014.

In March 2014 there were 584 children in detention centres on mainland Australia and 305 children detained on Christmas Island. A further 179 children were detained on Nauru.

This report gives voice to these 1068 children. It describes their circumstances and the impacts that detention has had on their lives and on the lives of their parents.

Overwhelmingly, the children who were interviewed for this Inquiry describe detention in negative terms. While they feel safe from the physical harms they escaped in their home countries, they describe detention as ‘prison-like’, ‘depressing’ and ‘crazy-making’.

4.1 Nationalities of the children in detention

The majority of children in detention centres travelled to Australia by boat without a visa. They came from over 20 different countries, the largest group being born in Iran. The second largest group were children with no recorded citizenship or nationality who identified as ‘stateless’ and are predominantly of Rohingya ethnic origin; a minority group who suffer systematic discrimination in Myanmar.[33]

Other major groups of children include those from Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia respectively. See Chart 5 for information about the recorded nationalities of children in detention.

Chart 5: Children in detention by nationality, 31 March 2014

Chart 5 Description: Children in detention by nationality. Iran 286, Stateless 168, Sri Lanka 119, Vietnam 104, Iraq 48, Afghanistan 38, Somalia 33, Myanmar/Burma 27, Lebanon 18, Pakistan 16, Other 9, Egypt 5, India 5, Nepal 3, Indonesia 2, Malaysia 2, Palestinian Authority 2, Syria 2, Sudan 1

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection [34]

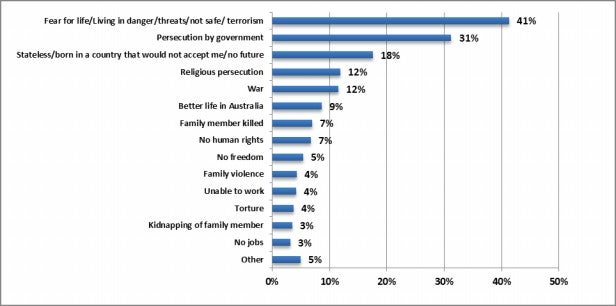

4.2 Reasons for seeking asylum

Almost all of the children in detention centres are asylum seekers who arrived in Australia by boat and are classified under the Migration Act as ‘unauthorised maritime arrivals’.[35]

As part of the Inquiry interview process, children and their parents were asked to explain why they decided to come to Australia. The most common response was ‘fear for life or safety’. The second most common response was that they were ‘escaping persecution by government’. Their responses are detailed in Chart 6.

Chart 6: Responses by children and parents to the question: Why did you come to Australia?

Chart 6 Description: Why people came to Australia? Fear for life/living in danger/threats/not safe/terrorism 41%, Persecution by government 31%, Stateless/born in a country that would not accept me/no future 18%, Religious persecution 12%, War 12%, Better life in Australia 9%, Family member killed 7%, No human rights 7%, No freedom 5%, Family violence 4%, Unable to work 4%, Torture 4%, Kidnapping of family member 3%, No jobs 3%, Other 5%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 833 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

Many children and parents spoke of conflict and a lack of safety in their homeland.

You know I’m Syrian, my country has war that’s why I’m here. If my country was good I don’t need Australia.[36]

(Child, Nauru Regional Processing Centre, May 2014)

There was no safety or assurance of life in [country], we do miss our country but we have to safeguard our lives.

(Mother of 6 week old baby, Inverbrackie Detention Centre, Adelaide, May 2014)

Children and parents spoke of being targeted and persecuted for belonging to particular religious or ethnic minorities in their home countries.

I am originally from Iraq, I am Kurdish, and was forced to go to Iran. In 1982, they killed my father during a period of political unrest and conflict. They singled out our family ... arrested my older brother, he was sent to prison for four or five years, we were under surveillance, we had to move.

(Father of two children aged 7 and 11 years, Melbourne Detention Centre, May 2014)

I am a person who came from Myanmar. In our country, our Muslim people were unable to live properly. Our Muslim people were killed, tyrannised, persecuted and treated unjustly. Our religious institutes were burnt down. Our Muslim peoples were not allowed to sleep at night. Although the Thein Sein government knew about such unjust treatments, nothing was said, nothing was solved. As we could not bear these problems, we came to Australia to build a new life.[37]

(Child, Nauru Regional Processing Centre, May 2014)

Children and their parents were at pains to explain that their decision to come to Australia was not opportunistic, but rather borne out of necessity to escape the dangers in their homeland.

I am a thirteen years old boy that came to Australia with my parents and my eight years old brother for better and brighter future. We took the risk of this dangerous way because we had no other option. I heard Australian politicians say Iranian people come to Australia because of their economic problems. But we weren’t poor in our country. We weren’t hungry, homeless, jobless and illiterate. We immigrate because we had no freedom, no free speech and we had [a] dictatorship.[38]

(13 year old boy, Nauru Regional Processing Centre, May 2014)

Many children described instances of significant trauma that occurred before they arrived in Australia. For some, the difficult or terrifying boat journey to Australia from Indonesia compounded the horrors that they experienced in their home country.

My father and brother were killed. I saw death on the way here. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have to be.

(Unaccompanied child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 4 March 2014)

The Inquiry team requested statistics on children referred for torture and trauma counselling in detention. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the medical provider for detention centres, International Health and Medical Services, were unable to provide this information. Nevertheless, as this report demonstrates, there are many children who have experienced death close up, including murder of immediate family members. Many children in detention are extremely vulnerable and many are receiving torture and trauma counselling.

4.3 Age of children in detention

The majority of children in detention in Australia are of primary school age. The second largest group is that of pre-schoolers; being children aged 2 to 4 years old. Babies make up 17 percent of all children in detention. From January 2013 to March 2014, there were 128 children born to mothers in detention centres in Australia.[39]

Chart 7 details the ages of children in detention in Australia.

Chart 7: Children in detention by age, 31 March 2014

Chart 7 Description: Children in detention by age. Teenagers (13-17) 196, Primary school aged (5-12) 336, Preschoolers (2-4) 204, Babies (less than 2) 153

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[40]

4.4 Unaccompanied children

Some children make the journey to seek asylum in Australia without parents or an adult guardian.

In March 2014 there were 56 unaccompanied children in detention centres in Australia. Seventeen unaccompanied children were detained on the Australian mainland and 39 were held on Christmas Island. A further 27 unaccompanied children were detained on Nauru. The majority of unaccompanied children came from Afghanistan, Myanmar, Somalia and Iran. All are teenagers aged between 15 years and 17 years.[41]

While in Australia, under the Immigration (Guardianship of Children) Act 1946 (Cth) their legal guardian is the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection.

Unaccompanied children are particularly vulnerable in detention because they are without any family.

Sometimes I have nightmares about the past but there’s no parent figure here to assist. I live in fear and I have lost my parents.

(Unaccompanied child, aged 16 years, Phosphate Hill, Christmas Island Detention Centre, 4 March 2014)

Being without my family, I was very alone and sad. At 14, I didn’t know what to do. I had to find an Iranian family who I got friends with. They helped me. If they didn’t help me I would have been sick and sad.[42]

(Unaccompanied child, previously detained on Christmas Island, May 2014)

4.5 When did the children arrive in Australia?

Under current Government policy all asylum seekers who arrived by boat on or after 19 July 2013 are to be transferred to Nauru or Manus Island detention centres unless the Minister determines otherwise.[43] This policy was introduced by the previous Labor Government in 2013 and has been continued by the current Coalition Government.

Chart 8 shows that most of the children in detention arrived between June 2013 and September 2013. There are approximately 520 children in Australia, including 50 unaccompanied children, who arrived on or after 19 July 2013, and are subject to transfer to Nauru.[44]

Chart 8: Children detained as at 31 March 2014 by month of arrival, May 2012 to March 2014*

Chart 8 Description: Children detained by month of arrival. Jan-13 0, Feb-13 4, Mar-13 13, Apr-13 69, May-13 58, Jun-13 97, Jul-13 248, Aug-13 158, Sep-13 55, Oct-13 28, Nov-13 22, Dec-13 62, Jan-14 14, Feb-14 19, Mar-14 21

*Includes babies born in detention and six children in detention who are not unauthorised maritime arrivals.

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[45]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection informed the Inquiry that the significant increase in boat arrivals during 2013 placed increased pressure on detention centre services, particularly those on Christmas Island. The Department acknowledges that the significant increase of boat arrivals was not a justification for inadequacies in service provision. The Department continued to work in an effort to meet the changed circumstances with the support of its service providers.

4.6 How long are children kept in detention?

Under Australian law, there is no prescribed limit to the time a child can be detained. Asylum seekers have no idea when their refugee status will be assessed or how long they will be held in detention. Many children and their parents lamented the uncertainty of their detention and the lack of information about what to expect in the future. Some told the Inquiry that even prisoners know the end date to their sentence.

Prisoners have better treatment. We don’t know when we will be free ... Our hope is slowly going. Maybe I will be killed like Reza Berati on Manus Island.

(Unaccompanied child, Phosphate Hill Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 4 March 2014)

In March 2014, children in Australian detention centres had been held for 231 days (approximately 8 months) on average. By September 2014, the average length of detention for children and adults was one year two months.[46]

Chart 9 shows that teenagers and primary school aged children have been detained for the longest period of time compared with pre-schoolers and babies.

Chart 9: Average length of detention (days) by age group, March 2014

Chart 9 Description: Average length of detention by age group. Teenagers (13-17) 262, Primary school aged (5-12) 269, Preschoolers (2-4) 237, Babies (less than 2) 170

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[47]

Chart 10 shows that the population of children in detention dropped in the period July 2013 to January 2014 while the length of detention increased.

Chart 10: Number of children in detention and length of time in detention, July 2008 to January 2014

Chart 10 Description: Number of children in detention and length of time. Children detained for more than 3 months Jul-13 around 400, Children detained for more than 3 months Jan-14 around 900. Total children detained Jul-13 around 1700, Total children detained Jan-14 around 1000.

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[48]

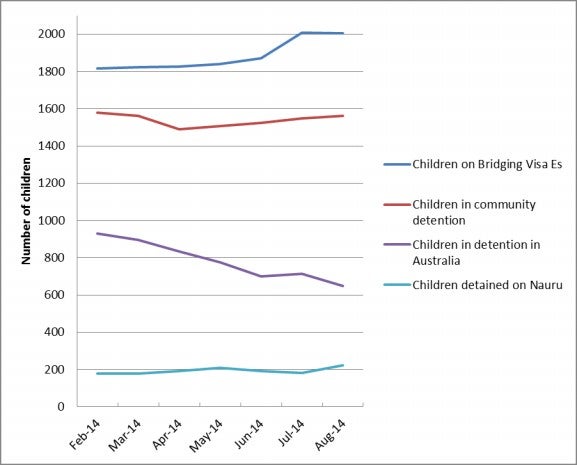

During the period of the Inquiry, the numbers of children in detention on mainland Australia and Christmas Island were reducing. The reasons for this reduction were that children were being released on bridging visas, children were being moved into Community Detention, or children were being transferred to detention on Nauru. Chart 11 shows the reducing numbers of children in detention in Australia and the increase in numbers of children released into the community or moved to detention on Nauru.

Chart 11: Numbers of children in detention in Australia, on Bridging Visa E, in Community Detention and in detention on Nauru by month, February 2014 to August 2014

Chart 11 Description: Children on bridging Visa Es Feb-14 around 1800, Children on bridging Visa Es Aug-14 around 2000. Children in community detention Feb-14 around 1600, Children in community detention Aug-14 around 1580. Children in detention in Australia Feb-14 around 950, Children in detention in Australia Aug-14 around 600. Children detained in Nauru Feb-14 around 200, Children detained in Nauru Aug-14 around 220.

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission analysis of data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[49]

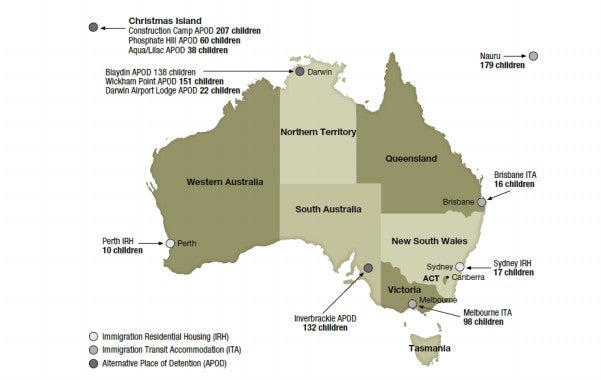

4.7 Movement of children across the detention network

Many children detained in Australia have been moved between different detention centres. Children are moved for many reasons, including access to healthcare, or other services that are not available in their current centre. Seventy-one percent of children and parents reported that they had been moved at least once.[50]

Some children had been moved to Australia from Nauru for health reasons. Others were brought back from Nauru or Papua New Guinea because they were incorrectly age assessed. Families are also temporarily moved to the mainland from Christmas Island or Nauru for health reasons and mothers are moved for the delivery of their babies.[51] Within a few weeks of delivery, new mothers are returned to Christmas Island. Mothers of newborns from Nauru had not been returned to Nauru at the time of writing this report.

Chart 12 shows the number of children in immigration detention in Australia and Nauru and the facilities where they are being held.

Chart 12: Children in detention by location, 31 March 2014

Chart 12 Description: Map showing children held in detention around Australia and offshore. Christmas Island - 305, darwin - 311, perth - 10, inverbrackie - 132, brisbane - 16, sydney -17, melbourne - 98, nauru - 179

Source: Adapted from Department of Immigration and Border Protection map[52]

4.8 Mental health and wellbeing of children in detention

Evidence to this Inquiry indicates that detention has significant negative impacts on the mental health and wellbeing of children. Eighty-five percent of children and parents indicated that their emotional and mental health had been affected since being in detention. There were no positive responses to detention - the most common impact on the emotional health of children and their parents were feelings of sadness and ‘constant crying’. Almost all children and their parents spoke about their worry, restlessness, anxiety and difficulties eating and sleeping in detention. Their responses are at Chart 13.

Chart 13: Responses by children and parents to the question: How has your emotional and mental health been impacted by detention?

Chart 13 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: How has your emotional and mental health been impacted by detention? Always sad/crying 30%, Always worried 25%, Not eating properly/weight loss 12%, Restlessness/agitated 11%, Nightmares 9%, Not able to sleep well 9%, Clinging/anxious 8%, Fighting with others/aggressive 7%, Headaches 4%, Self-harming 4%, Won't leave the room 3%, Frightened to be alone 2%, Going crazy 2%, Nail biting 2%, Bed wetting/incontinence 2%, Problems toileting/holding on 2%, Shouting/screaming 1%, Other 12%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 327 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

The mental health screening of children in detention shows alarming results both in the rates of mental disorder in these children and in the severity of their symptoms.

Detention medical staff conducted mental health assessments of 243 children aged between 5 to 17 years in detention centres in Australia and on Christmas Island from April 2014 to June 2014.

Results from these assessments show that 34 percent of children had mental health disorders that would be comparable in seriousness to children referred to hospital-based child mental health out-patient services for psychiatric treatment.[53] Less than two percent of children in the Australian population have mental health disorders at this level.

The former Director for Mental Health, International Health and Medical Services described these results as ‘very concerning’.[54]

... it’s quite clear that we’ve got a large number of children with significant mental distress and disorder in this population.[55]

The screening tool used to assess children and adolescents in detention from April to June 2014 was the Health of the Nation Outcomes Scales for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA). While this tool is used as part of routine clinical practice in mental health services in Australia, it has only recently been introduced into detention centres for assessing children. [56] Therefore this 2014 data is the only clinical data that can be used as a baseline to assess the mental health of children in detention as a cohort.

... the HoNOSCA is ... used in Australian mental health services universally ... it's part of the standard outcome measures ... it’s considered to be reliable and a measure which is useful to apply in different populations and that’s why it’s chosen for that purpose.[57]

The HoNOSCA has a 5 point scale which measures the severity of mental health disorders across different behaviours, symptoms and social functioning.

0 = no problem, 1 = minor problem requiring no action, 2 = mild problem but definitely present, 3 = moderately severe problem, 4 = severe to very severe problem.[58]

The HoNOSCA assesses mental health across four domains: behavioural items, impairment items, symptom items and social items. According to HoNOSCA assessments, children in detention show very high levels of emotional disorder, over activity, poor concentration and impairments in scholastic and language development.

Chart 14 shows the HoNOSCA scores of children with (i) mild but present mental health problems and (ii) moderately severe to very severe mental health problems.

Chart 14: Percentages of children with (i) mild but present mental health problems and (ii) moderate to very severe mental health problems; HoNOSCA scores of children in Australian detention centres, April – June 2014[59]

Chart 14 Description: Percentages of children with (i) mild but present mental health problems and (ii) moderate to very severe mental health problems; HoNOSCA scores of children in Australian detention centres, April – June 2014. Emotional or related symptoms (mild but present problem) - 20%. Emotional or related symptoms (moderately severe to very severe problem) - 15%.

Research demonstrates that prolonged and uncertain periods of detention both cause and exacerbate mental illness; for example:

- In 2004 psychiatric assessments of families held in immigration detention for more than two years revealed that ‘adults displayed a threefold and children a tenfold increase in psychiatric disorder subsequent to detention’ and that ‘the majority of adults and children had more than one psychiatric disorder’; and

- In 2010 the Australian Government commissioned a study by Janette P Green and Kathy Eagar to analyse the health records of 700 people in immigration detention. The study found that ‘there is a clear association between time in detention and rates of mental illness.’[60]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection, the Australian Government and the Opposition accept the detrimental mental health impacts of prolonged detention on children.[61] In evidence to the Inquiry at the third public hearing, the Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection discussed the negative impacts of prolonged detention:

... there is a reasonably solid literature base which we’re not contesting at all which associates a length of detention with a whole range of adverse health conditions.[62]

Despite acknowledging these long term impacts, when the Department was presented with the first HoNOSCA data, the Head of Detention Health Operations asked that this data not be provided in future reports, pending further consideration. The email making this request is reproduced below:

We’d be grateful if both the HoNOS and HoNOSCA data could be withheld from both of the quarterly data sets pending further consideration by the Department and discussion with IHMS.[63]

The HoNOSCA assessments provide the first set of comprehensive clinician-rated data which allow for assessments of the long term impacts of detention on children as individuals and as a cohort. This data is essential to track and map how children are progressing over time and whether the detention environment has specific impacts on children. It is the most reliable method for medical staff to assess whether the mental health of children is deteriorating or improving. It can tell the Department of Immigration and Border Protection this same information.

Children in detention have had periodic mental health assessments for several years. This involves an initial mental health assessment when they enter detention, a more comprehensive follow up assessment that occurs between 10 and 30 days in detention, and periodic assessments at 6 months, 12 months and every 3 months thereafter. At 18 months there is a separate review by a psychiatrist. The assessments were conducted in the same way for adults and children and involved a general health questionnaire and the use of a self-reporting instrument.

However, prior to 2014, no consistent child-specific mental health assessment tool has been applied during the years that children have been detained in Australian detention centres.

There is no doubt that the children themselves have noticed the impacts of detention on their emotional and mental health. Children spoke openly about the stressors of the detention environment to Inquiry staff.

Living here is hard. The tension in here and the tension from home. Too much sad[ness] ... whenever I call home they ask when I will be released. I tell them Inshalla (God willing) ... Many people here are hurting themselves. Boys cutting hands, arms ... I was thinking about that.

(Unaccompanied child, Christmas Island, 4 March 2014)

I’ve changed a lot, I’m not fun anymore. I’m just thinking about bad stuff now ... I was thinking of become a doctor but not anymore.

(15 year old child, Nauru Detention Centre, May 2014)[64]

We are getting crazy in here.

(Unaccompanied child, Nauru Detention Centre, May 2014)[65]

It affects the people’s mind and the children too. They have 10 months on the detention that means they get crazier and upset.

(Unaccompanied child, Nauru Detention Centre, May 2014)[66]

4.9 Detention is a dangerous place

From January 2013 to March 2014 there were numerous assaults and self-harm incidents in detention centres in Australia where children are held. They include:

- 57 serious assaults

- 233 assaults involving children

- 207 incidents of actual self-harm

- 436 incidents of threatened self-harm

- 33 incidents of reported sexual assault (the majority involving children); and

- 183 incidents of voluntary starvation/hunger strikes (with a further 27 involving children).[67]

The Commission is deeply concerned by these numerous incidents of assault, sexual assault and self-harm. The Commission has viewed the case files detailing incidents of reported sexual assaults involving children. Given the seriousness of these incidents, the Commission considers that some may come within the scope of the terms of reference of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. The Commission intends to communicate these concerns to the Royal Commission.

In instances where Commission staff were advised of sexual assaults involving children, these were reported to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. It is understood that the Department is investigating all incidents of sexual assault.

4.10 Rates of self-harm amongst children

The level of mental distress of children in detention is evident by very high rates of self-harm. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection confirmed that during a 15 month period from January 2013 to March 2014, 128 children in detention engaged in actual self-harm. One hundred and seventy-one children threatened self-harm.[68] The age of children involved in self-harm ranged from 12 to 17 years old.[69]

One hundred and five children in detention were assessed under the Department’s Psychological Support Program as being of ‘high imminent risk’ or ‘moderate risk’ of suicide or self-harm and required ongoing monitoring. Ten of these children were aged 10 years or younger.[70]

The following extracts from the Department’s ‘Incident Detail Reports’ document individual acts of self-harm by children.[71] These reports reveal that many children attribute their self-harming behaviour to the conditions and length of time in detention; their feelings of isolation and uncertainty; and their reactions to news about their immigration status.

Client stated to Serco his sister is getting married next Monday back in his country and he was really angry and frustrated because he can’t make his presence in the family function. He also said he is getting more upset whenever he thinks too much about his prolonged detention life.

(Report concerning a 17 year old boy who was found with ten self-inflicted cuts to his forearm)

He told me that he had been feeling stressed for the last two days, mainly because he missed his friends and Aunty in Canada ... he had been having thoughts race through his head and wanted to stop them.

(Report concerning a 16 year old boy who drank insect repellent)

When asked, M said that he had cut himself due to being in detention for a long time and that he was tired of being here.

(Report concerning a 17 year old boy who during a 15 month period self-harmed on nine occasions and threatened self-harm on two occasions)

[He] inflicted several small cuts to his right arm and attributed this to a feeling of sadness as he is still in detention and cannot provide support for his family. This has been made worse by other clients telling Master B that he would be in detention for at least 9 months because he has family in Australia.

(Report concerning a 15 years old boy who inflicted several cuts to his forearm).

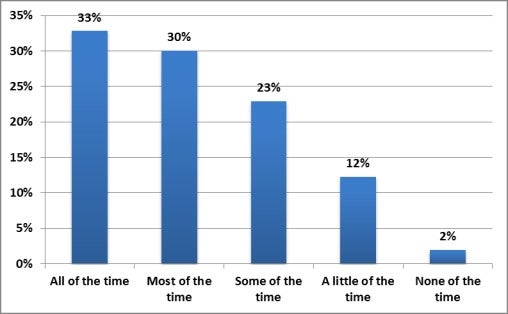

4.11 Mental health of parents

Parents in detention are suffering from high rates of mental distress, mental ill-health and trauma according to evidence provided to the Inquiry. According to the Regional Director of Medical Services for International Health and Medical Services, 30 percent of adults have a mental health problem and the severity and rates of these problems increase with the length of time in detention.[72]

... a clinician rated tool ... shows that as in adults we have about 30% of people with mental health issues and that is linked and increases with the length of the time in detention. We would assume that is a similar picture in children and adolescents...[73]

The mental health assessments show that 30 percent of adults had moderate to severe mental health conditions when they were tested between January and March 2014.[74]

Only two percent of parents reported to the Inquiry that they were not depressed at any time while 33 percent of parents reported that they felt depressed all of the time. Their responses are at Chart 15.

Chart 15: Responses by parents to the question: How often do you feel depressed?

Chart 15 Description: Responses by parents to the question: How often do you feel depressed? All of the time 33%, Most of the time 30%, Some of the time 23%, A little of the time 12%, None of the time 2%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 253 respondents

The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire is the tool that is used to test for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Medical staff in detention centres conducted an assessment of 251 adults in detention; specifically adults who reported torture and trauma experiences. These assessments found high rates of elevated trauma scores, with 38 percent having a score that is indicative of a clinical diagnosis of PTSD.[75]

These rates are significantly higher than in the Australian population where 6.4 percent of the population is likely to be suffering from this condition at any given time.[76]

According to the Detention Health Framework and the Departmental policy for Identification and Support of Survivors of Torture and Trauma, people with symptoms of PTSD should be in less restrictive community based detention and all should have their refugee cases dealt with expeditiously.[77]

Mentally unwell adults can have negative impacts on the development of children. When parents are mentally unwell, the probability of harm increases because parents have a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of their child’s life.[78]

... offspring of depressed parents have rates of depression that are between two and four times higher than their counterparts from homes without parental illness. These offspring also have an increased risk for a range of mental health disorders.[79]

The high rates of depression and unhappiness amongst parents are causing anxiety amongst children in detention.[80] Parents expressed their concerns about these impacts on children.

It’s not very safe – their father is sad and depressed. [We] try not to show kids but they see. When I cry, my daughter asks ‘why crying?’

(Mother of pre-schooler, a primary school aged child and baby, Blaydin Detention Centre, Darwin, 12 April 2014)

A number of parents reported serious mental health problems and attempts at suicide or self-harm. In one case a mother who had made three suicide attempts reported that she had thoughts of harming her children.

Dying is better than living ... I want to die ... I cannot tolerate this environment.

[I] lock myself in room; I lose it sometimes; I become agitated. They [Department of Immigration and Border Protection] made me sick ... [I am] no longer having thoughts of harming my children, but they are surviving, not living ... my children say we don’t want Australia, we want you alive.

(Mother of children aged 6 months, 8 and 11 years who has attempted suicide three times and has ongoing suicidal ideation, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

A mother who had been transferred from Nauru to Melbourne Detention Centre for medical reasons after making two suicide attempts said: ‘I’m a nervous wreck’.[81]

Every day they come home [from school] and ask us [is there any news]...The only thing that keeps me going is my children and hope for my children.

(Father of two children aged 11 and 7 years, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

A mother of three who had self-harmed on Christmas Island expressed her distress:

Enough is enough. I have had enough torture in my life. I have escaped from my country. Now, I prefer to die, just so my children might have some relief. I have reached the point I want to hand over my kids.

(Mother of three children, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 17 July 2014)

Medical experts assisting the Inquiry described mental health impacts on both parents and their children in the following terms:

Almost all parents reported that they themselves had symptoms of depression, anxiety or were on anti-depressant medication, and that their children had poor sleep, nightmares, poor appetite and behavioural problems.[82]

4.12 Children with disabilities

In July 2014 there were 28 children in detention who were assessed as having a disability.[83] These children had spent 11 months in detention on average and are aged between 2 and 17 years old.[84]

The types of disabilities include:

- Hearing disabilities

- Vision disabilities

- Developmental disabilities including autism, developmental delays, conduct disorder, reactive attachment disorder

- Functional impairments including congenital heart disease and muscular dystrophy

- Epilepsy

- Spinal deformity

- Congenital kidney anomaly[85]

In July 2014 there were 36 children in detention who were assessed as having a mental illness or a mental health disorder. Chart 16 shows the ages of these children and types of mental health disorder.

Chart 16: Children in detention assessed as having a mental health disorder / illness, 10 July 2014

| Age of child | Nature of mental health disorder | Months in detention at July 2014 |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Childhood or adolescent disorder or social functioning attachment disorder | 11 |

| 3 | Depression | 11 |

| 7 | Adjustment disorder; mixed anxiety disorder of social functioning; attachment disorder | 9 |

| 7 | Adjustment disorder; depressive disorder | 11 |

| 7 | Adjustment disorder | 11 |

| 7 | Anxiety disorder; post-traumatic disorder | 11 |

| 8 | Anxiety disorder; personality disorder (post-injury) | 11 |

| 8 | Anxiety disorder; major depressive disorder | 16 |

| 9 | Depressive disorder | 12 |

| 9 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 9 | Adjustment disorder; mixed anxiety and depressive disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 9 | Adjustment disorder; mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 12 |

| 9 | Anxiety disorder | 15 |

| 10 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 12 |

| 10 | Anxiety disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 11 | Depression | 11 |

| 11 | Depressive disorder | 11 |

| 12 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 12 |

| 12 | Adjustment disorder; depressive disorder | 11 |

| 13 | Depression – psychotic; mixed anxiety and depressive disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 13 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 7 |

| 14 | Depression; disorder – adjustment | 12 |

| 14 | Adjustment disorder; anxiety disorder; depressive disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 14 | Depressive disorder; mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 11 |

| 15 | Adjustment disorder; depressive disorder | 11 |

| 15 | Anxiety disorder; depressive disorder; personality disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 11 |

| 15 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 11 |

| 15 | Depressive disorder | 11 |

| 16 | Adjustment disorder; mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 11 |

| 16 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 7 |

| 16 | Depression | 14 |

| 16 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 8 |

| 16 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 12 |

| 17 | Adjustment disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder | 10 |

| 17 | Anxiety with depression; disorder – bipolar; mood disorder; depressed mood | 11 |

| 17 | Depression; disorder – bipolar; adjustment disorder; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 11 |

Source: Data from Department of Immigration and Border Protection[86]

Case Study 1: Family with hearing disability in detention

The following case study is of a family comprising two profoundly deaf adults and their profoundly deaf child. This family initially met the Inquiry team on Christmas Island in March 2014. They were later moved to a detention centre in Darwin where the Inquiry team met them for a second time in April 2014. At the second meeting the child was 19 months old.

The parents reported that their hearing aids had been ruined on the boat journey to Australia. Their 19 month old daughter had no hearing aid. At the time Inquiry staff met with the family they had been in detention for over six months, being three months on Christmas Island and three months in Darwin. During this time they had no hearing aids and were unable to communicate with anyone in the detention centre without extreme difficulty.

The parents said that they felt socially isolated because they could not communicate with other people and they were unsure about what their future held because they didn’t understand the conditions of their detention. They also reported concerns about their baby’s language development without a hearing aid, telling the Inquiry that their baby was ‘not using her voice at all’.

They said that they struggled to communicate and to play with her, and were not able to hear when she was crying.

The first language of both parents is sign language and they reported that they often had to rely on a Farsi interpreter to communicate with Departmental officials, Serco officers and medical staff. The lack of a sign language interpreter meant that the parents had to lip-read. This made communication and comprehension extremely difficult.

The parents had their hearing assessed in December 2013 and were fitted with hearing aids in May 2014, seven months after they first arrived in Australia. The child also had an audiology appointment in December 2013. As of August 2014 she was being assessed for the most appropriate hearing assistance

4.13 Children’s views about detention

Children and their parents consistently described detention as a ‘prison’. Many described the sense of injustice they felt at having fled unsafe situations to now be held in detention.

I left my country because there was a war and I wanted freedom. I left my country. I came to have a better future, not to sit in a prison. If I remain in this prison, I will not have a good future. I came to become a good man in the future to help poor people ... I am tired of life. I cannot wait much longer. What will happen to us? What are we guilty of? What have we done to be imprisoned?[87]

I’m just a kid, I haven’t done anything wrong. They are putting me in a jail. We can’t talk with Australian people.

(13 year old child, Blaydin Detention Centre, Darwin, 12 April 2014)

We came from war and were hoping for freedom here. My own country never locked me up. Here there are women’s rights but we are locked up.

(Mother of a 9 month old baby, Inverbrackie Detention Centre, Adelaide, 12 May 2014)

Children in detention live in very different circumstances depending on where they are detained and their housing conditions vary dramatically. They range from tents on Nauru, to ‘containerised accommodation’ on Christmas Island to suburban style housing villas at Inverbrackie, Adelaide.

As part of the Inquiry questionnaire, Inquiry staff asked children and their parents to describe their experience of immigration detention in three words – positive or negative. Their responses in Chart 17 reveal overwhelmingly negative sentiments.

Chart 17: Responses by children and parents to the question: Use three words to describe the experience of detention

Chart 17 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: Use three words to describe the experience of detention. Sad/unhappy/depressing/mentally affecting/crazy making 36%, No freedom/want to leave/restricted/powerless 26%, Awful/horrible/bad/unsettling/don't like it 21%, Jail/prison/captivity 21%, Unsafe/worrying/scary/bullying/frightening/fighting 19%, Nothing to do/boring/watching time/frustrating/no school 15%, Harsh/difficult 10%, Hopeless 9%, Bad for children 8%, Peace/safe from harm 7%, Heart ache/painful 4%, Shameful/inhuman/no respect 4%, Not fair/unjust/cruel 4%, Death/want to die 4%, Exhausting 3%, Frustrating 3%, Other 9%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 723 respondents (Note: respondents can provide multiple responses)

Children and their parents were asked to describe their emotional state since arriving in Australia and living in detention. Despite having left conflict zones or having fears for their safety in their home country, 49 percent of children and their parents were not happier since arriving in Australia. Their responses are at Chart 18.

Chart 18: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you happier since coming to Australia?

Chart 18 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you happier since coming to Australia? Certainly true 34%, Sometimes true 18%, Not true 49%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 530 respondents

The high levels of unhappiness amongst children and their parents may be partially explained by the fact that 61 percent of children and their parents were not relaxed in the detention environment. Only 16 percent of respondents described feeling relaxed in detention. Their responses are at Chart 19.

Chart 19: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you relaxed in your current living arrangements?

Chart 19 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you relaxed in your current living arrangements? Certainly true 16%, Sometimes true 23%, Not true 61%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 459 respondents

High numbers of children and parents reported that they have many worries in detention. Seventy-two percent of children and their parents said that they often feel worried at Chart 20.

Chart 20: Responses by children and parents to the question: Do you have many worries or often feel worried?

Chatr 20 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: Do you have many worries or often feel worried? Certainly true 72%, Sometimes true 16%, Not true 12%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 462 respondents

Many children and their parents described the boredom and frustration of the detention environment with few opportunities for recreation or education.

There is nothing to do here, only eating, sleeping, [and] English classes.

(Unaccompanied child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 4 March 2014)

I want to study more; I can’t study when I am living here. At my age I can’t learn with other children. When I go to school the Principal says I can’t be with Australian children, they keep us separate. I want to be with Australian children. I am waiting for the day I can study like Australian children. It’s very awful.

(14 year old girl, Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin, 11 April 2014)

Can we have some toys please? Here there are only baby toys. We’d like some cars to play with, Lego, a bicycle. We have no visitors, no toys.

(Child aged 12, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

Children should not be in detention because there is nothing to do, just eat, sleep ... no school, no sport, nothing, no idea about what will happen ... . One day I tried to go to gym but they said I am too young for gym. It was very hot. We just slept.[88]

Children spoke of the hopelessness which they felt about the future, the lack of certainty about a timeframe for the assessment of their refugee claims and the fear of being sent to Nauru or Manus Island.

I have many problems in the camp. I cannot find peace. If I am released from the camp that would be good, if not, I will go crazy in this camp.[89]

(Unaccompanied 17 year old, Nauru Regional Processing Centre, May 2014)

My hope finished now. I don’t have any hope. I feel I will die in detention.

(Unaccompanied 17 year old, Phosphate Hill Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 4 March 2014)

Now I have lost my motivation to learn or speak English and this has stopped me from being able to learn. I came here for a better future. I feel pretty hopeless and that I won’t get anything out of this. Every time I go to bed I have flashbacks from the times I was on the sea and the situation we are in now ... it is hopeless.

(Unaccompanied 15 year old, Bravo Compound, Christmas Island Detention Centre, 16 July 2014)

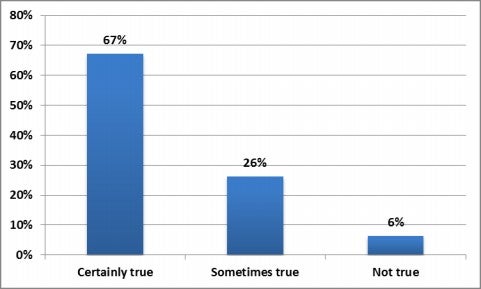

Chart 21 shows that 67 percent of children and their parents were often unhappy, depressed or tearful.

Chart 21: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you often unhappy, depressed or tearful?

Chart 21 Description: Responses by children and parents to the question: Are you often unhappy, depressed or tearful? Certainly true 67%, Sometimes true 26%, Not true 6%

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 483 respondents

4.14 The right to identity

People were called by boat ID. People had no value. No guards called me by name. They knew our name, but only called by boat ID.

(Boy who was detained as a 16 year old, Community Interview, Sydney, 5 August 2014)

Almost 50 percent of detainees who spoke with the Inquiry at Christmas Island and Darwin detention centres reported that Serco officers called them by a boat ID rather than their name. A boat ID comprises a few letters and numbers given to asylum seekers who arrive by boat. It is a unique identifier provided to each individual by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

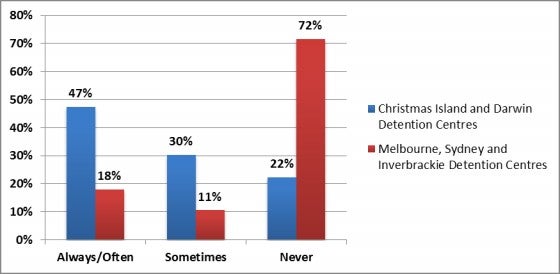

Asylum seekers who are subject to the 19 July 2013 policy of transfer to Nauru or Manus Island are much more likely to be called by their boat ID than other asylum seekers. Asylum seekers who arrived on or after 19 July 2013 are detained at Christmas Island and large numbers are temporarily located at Darwin where they can receive health treatment. Chart 22 shows how often people in different detention centres reported being identified by their boat ID.

Chart 22: Responses of children and parents to the question: How often are you identified by your boat ID?

Chart 22 Description: Responses of children and parents to the question: How often are you identified by your boat ID (Melbourne, Sydney and Inverbrackie Detention Centres listed first; Christmas Island and Darwin Detention Centres listed second)? Always/often 47% and 18%, Sometimes 30% and 11%, Never 22% and 72%)

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia 2014, 234 respondents

Paediatrician Professor Elliott noted that on Christmas Island ‘detainees refer to themselves by their ‘boat number’ in written and oral communication.’[90] More than 30 percent of children on Christmas Island signed their drawings with their boat ID before presenting them to Inquiry staff.

Boat number has become like our first name.

(13 year old child, Blaydin Detention Centre, Darwin, 12 April 2014)

Australia has an obligation under article 8(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child to ‘respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including nationality, name and family relations as recognized by law without unlawful interference.’

A child rights NGO, ChilOut, reported that ‘children in detention respond to their boat ID numbers and know their friends’ ID numbers.’[91]

So institutionalised are people, that families with newborn babies were worried when their babies had no ID tag. Some families were at a loss to understand where their baby officially fitted given he/she was not Australian, was not a national of the parent’s homeland and did not even have a Serco ID tag.[92]

The Commission has long held that referring to children by a boat ID is dehumanising.[93] This view is supported by Dr Mares and Professor Elliott who assisted the Inquiry team on visits to Christmas Island.[94] Some of the children told Inquiry staff that it made them feel like criminals. One unaccompanied 17 year old detained on Christmas Island said ‘I feel like a killer when they use my boat number’.

4.15 Inquiry findings relevant to all children in detention and to children held on Christmas Island

The findings of this chapter relate to all children in detention and cover the issues that affect children in detention as a total cohort. The findings in this chapter are also relevant to children held on Christmas Island.

The findings in other chapters are divided according to the child’s stage of life. Chapters 6 to 9 contain findings about babies, preschoolers, primary school aged children and teenagers, respectively.

Chapters 10 to 12 contain findings in relation to specific cohorts of children including unaccompanied children, children who are indefinitely detained and children on Nauru.

Findings relevant to all children in detention

The mandatory and prolonged immigration detention of children is in clear violation of international human rights law.

Both current and former Ministers of Coalition and Labor governments stipulate that the detention of children is (and was) not intended as part of deterrence policy. They confirm that the detention of children would not, in fact, be a deterrent.

At the time of writing this report, adults and children have been in detention for over one year and two months on average, over 413 days. Children who arrived on, or after 19 July 2013, are to be transferred to Nauru. This transfer can happen at any time. Children are detained on Nauru and there is no timeframe for their release.

Current detention law, policy and practice does not address the particular vulnerabilities of asylum seeker children, nor does it afford them special assistance and protection. Mandatory detention does not consider the individual circumstances of children nor does it address the best interests of the child as a primary consideration. This is contrary to Australia’s obligations under article 3(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Detention for a period that is longer than is strictly necessary to conduct health, identity and security checks breaches Australia’s obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child to:

- detain children as a measure of last resort (article 37(b)) and for the shortest appropriate period of time (article 37(b))

- ensure that children are not arbitrarily detained (article 37(b))

- ensure prompt and effective review of the legality of their detention (article 37(d)).

The fact of detention and the environment in which children are detained impact on children’s health, development, safety and dignity.

Prolonged detention is having profoundly negative impacts on the mental and emotional health and development of children. In the first half of 2014, 34 percent of children in detention were assessed as having mental health disorders at levels of seriousness that were comparable with children receiving outpatient mental health services in Australia. Less than two percent of children in the Australian population were receiving outpatient mental health services in 2014.[95]

Prior to 2014, the mental health assessments of children in detention were not conducted using child-specific, clinician-rated measuring tools. Therefore, there is limited clinical data about the mental health impacts of detention on children over time.

The introduction of the mental health assessment tool (the HoNOSCA) into the detention system in 2014 provides a standardised measure for mental health assessments of children and benchmark data against which to assess the mental health progress of individuals and cohorts over time.

The clinical data collected by International Health and Medical Services is consistent with extensive medical research about the mental health impacts of detention on children and adults.

Eighty-five percent of children and parents indicated that their emotional and mental health had been affected since being in detention.

Despite the best efforts of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and its contractors to provide services and support to children in detention, it is the fact of detention itself that is causing harm. In particular the deprivation of liberty and the exposure to high numbers of mentally unwell adults are causing emotional and developmental disorders amongst children.

Given the profound negative impacts on the mental and emotional health of children which result from prolonged detention, the mandatory and prolonged detention of children breaches Australia’s obligation under article 24(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Article 24(1) provides that children have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has explained that ‘health’ in article 24 should be understood as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (see General Comment No 15, paragraph 4). The right to the highest attainable standard of mental health is an essential aspect of the guarantee provided by article 24(1).

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has stated that it interprets children’s right to health in article 24 as an inclusive right, which extends ‘to a right to grow and develop to their full potential and live in conditions that enable them to attain the highest standard of health’. (General Comment No 15, paragraph 2).

The fact of detention and the environment in which children are detained also have a range of impacts on children’s development, safety and dignity. Chapters 6 to 13 of this report examine in more detail the impact of detention experienced by children at different stages of their development. Based on the work undertaken in the course of the Inquiry, the Commission concludes that at various times children in immigration detention were not in a position to fully enjoy their rights under articles 6(2), 19(1), 24(1), 27 and 37(c) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Under articles 6(2) and 27 of the Convention, children have a right to a standard of living adequate for their physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development (article 27(1)), and States have an obligation to ensure this development ‘to the maximum extent possible’ (article 6(2)). The Committee on the Rights of the Child has reminded States in General Comment No 7 (at paragraph 10):

that article 6 encompasses all aspects of development, and that a young child’s health and psychosocial wellbeing are in many respects interdependent. Both may be put at risk by adverse living conditions, neglect, insensitive or abusive treatment and restricted opportunities for realizing human potential.

The restrictive detention environment clearly limits children’s opportunities for development in terms of experiences and social interactions.

Children are also entitled to be protected from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse (article 19(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child). This is consistent with their right to the highest attainable standard of (physical) health in article 24(1) of the Convention.

However, children in detention are exposed to danger by their close confinement with adults who suffer high levels of mental illness. Thirty percent of adults detained with children have moderate to severe mental illnesses. There are also significant rates of incidents of violence (including assaults and sexual assaults) in detention centres in which children are detained; many of the incidents directly involve children.

The numerous reported incidents of assaults, sexual assaults and self-harm involving children indicate the danger of the detention environment.

Children in detention also have the right to be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age (article 37(c) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child). Practices in detention centres on Christmas Island and in Darwin of referring to children by their boat IDs rather than their names do not respect the inherent dignity of those children. The requirement that Serco officers conduct head counts four times a day, including by entering children’s bedrooms at night, also encroaches upon children’s dignity. Article 37(c) is most relevant to the conditions faced by children detained on Christmas Island.

Findings in relation to conditions of detention on Christmas Island

Children and their families frequently describe detention as punishment for seeking asylum. The feeling of unfairness is particularly strong amongst people who arrived on or after 19 July 2013.

Conditions of detention vary widely across the detention network and this has a differential impact on the physical health of children. The harsh and cramped living conditions on Christmas Island create particular physical illnesses amongst children.

The children in detention on Christmas Island live in cramped conditions. Families live in converted shipping containers the majority of which are 3 x 2.5 metres. Children are effectively confined to these rooms for many hours of the day as they are the only private spaces that provide respite from the heat. Up until July 2014, families living in the (now closed) Aqua and Lilac Detention Centres shared common bathroom facilities with everyone in those centres.

Children currently detained on Christmas Island had almost no school education for the period; from July 2013 to July 2014. The Department rectified the situation in July 2014.

At various times children detained on Christmas Island were not in a position to fully enjoy the following rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child as a result of their living conditions in detention:

- the right to enjoy ‘to the maximum extent possible’ the right to development (article 6(2))

- the right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 24(1))

- the right to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development (article 27(1))

- the right to be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age (article 37(c)).

In relation to the right to be treated with humanity and respect, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasised that in all situations where children are in detention they should:

be provided with a physical environment and accommodations which are in keeping with the rehabilitative aims of residential placement, and due regard must be given to their needs for privacy, sensory stimuli, opportunities to associate with their peers, and to participate in sports, physical exercise, in arts, and leisure time activities. (General Comment No 10, paragraph 89)

The Commission finds that the failure of the Commonwealth to provide education to school aged children on Christmas Island between July 2013 and July 2014 is a breach of the right to education in article 28(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

[32]Name withheld, unaccompanied child detained in Nauru OPC Submission No 141 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20141%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Unaccompanied%20child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 2 October 2014).

[33]Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tomas Ojea Quintana, April 2014 p 13. At http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/MM/A.HRC.25.64.pdf (viewed 8 September 2014).

[34]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[35] Migration Act 1958 (Cth) s 5AA

[36]Name withheld, child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 95 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2095%20-Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 2 October 2014).

[37]Name withheld, child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 151 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20151%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 2 October 2014).

[38]Name withheld, boy currently in immigration detention, Submission No 215 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20215%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Boy%20currently%20in%20immigration%20detention.docx (viewed 11 September 2014).

[39]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children born in immigration detention facilities as at 31 March 2014, Item 2, Document 2.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[40]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[41] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children born in immigration detention facilities as at 31 March 2014, Item 2, Document 2.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[42]Name withheld, Submission No 42 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2042%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20who%20lived%20in%20immigration%20detention%20previously.pdf (viewed 11 September 2014).

[43]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Submission No 45 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 8. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2045%20-%20Department%20of%20Immigration%20and%20Border%20Protection.pdf (viewed 2 October 2014).

[44]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[45]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[46]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary: 31 September 2014 (2014), p 10. At http://www.immi.gov.au/About/Pages/detention/about-immigration-detention.aspx (viewed 14 October 2014).

[47]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Data on children in immigration detention facilities, Item 3, Document 3.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[48]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[49]Data from the monthly Immigration Detention Statistics published by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. At http://www.immi.gov.au/About/Pages/detention/about-immigration-detention.aspx (viewed 30 September 2014).

[50]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Responses to question: How many times has this person been moved between detention centres in total? 714 respondents.

[51]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Submission No 45 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 14. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2045%20-%20Department%20of%20Immigration%20and%20Border%20Protection.pdf (viewed 20 August 2014).

[52]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[53] International Health and Medical Services, Data on screening children (HoNOSCA),Quarter 2; Apr to Jun 2014, Attachment 3, Second Notice to Produce, 24 September 2014. Data from IHMS was compared with data from the Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network for patients from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2013.

[54] Dr P Young, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Dr%20Young.pdf

(viewed 5 September 2014).

[55] Dr P Young, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Dr%20Young.pdf

(viewed 5 September 2014).

[56] Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network, Training Manual, Child & Adolescent, p 24. At http://amhocn.org/static/files/assets/7ceb5dda/Child_Adolescent_Manual.pdf (viewed 18 September 2014).

[57] Dr P Young, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Dr%20Young.pdf

(viewed 5 September 2014).

[58] International Health and Medical Services, Data on screening of children, Item 1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 24 July 2014.

[59] International Health and Medical Services, Data on HoNOSCA Scores of children in Australian Detention Centres, April – June 2014, Item 2, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 24 July 2014.

[60] Ipos Social Research Institute, Evaluation of the psychological Support Program (PSP) Implementation (June 2012), pp 50-51; J P Green and K Eagar, ‘The health of people in Australian immigration detention centres’ (2010) 192(2) The Medical Journal of Australia 65; Z Steel, S Momartin, C Bateman, A Hafshejani, D M Silove, Psychiatric status of asylum seeker families held for a protracted period in a remote detention centre in Australia’ (2004) 28(6) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health; L K Newman, N G Procter, M J Dudley ‘Suicide and self-harm in immigration detention’ (2011) 195(6) The Medical Journal of Australia pp 310-11, p 219.

[61] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 22 September 2014); The Hon Scott Morrison MP, Fourth Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Canberra, 22 August 2014, Canberra. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Hon%20Scott%20Morrison%20Mr%20Bowles.pdf (viewed 3 October); The Hon Chris Bowen MP, Fifth Public Hearing into the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 9 September 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 13 October 2014).

[62] Martin Bowles, Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Dr%20Young.pdf

(viewed 26 September 2014).

[63] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, email communication to International Health and Medical services, 28 July 2014, Item 1, Schedule 2, Third Notice to Produce, 12 August 2014.

[64] Name withheld, child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 98. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2098%20-Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 26 September 2014).

[65] Name withheld, Unaccompanied child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 92. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2092%20-Name%20withheld%20-%20Unaccompanied%20child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 11 September 2014).

[66] Name withheld, unaccompanied child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 95. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2095%20-Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 11 September 2014).

[67] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Incidents in facilities where children are held, Item 12, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 July 2014.

[68]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Deaths Self-harm and Incidents, Item 11, Document 11.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[69]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Actual Self Harm, Item 36, Schedule 3, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[70]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Deaths, Self-Harm and Incidents, Item 11, Document 11.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[71]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Item 36, Schedule 3, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[72] M Parrish, Director of International Health and Medical Services, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/International%20Health%20and%20Medical%20Services_0.pdf (viewed 2 September 2014).

[73] M Parrish, Director of International Health and Medical Services, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/International%20Health%20and%20Medical%20Services_0.pdf (viewed 2 September 2014).

[74]International Health and Medical Services, Results of mental health screenings in Australian Immigration Detention (adults), conducted Jan-Mar 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/International%20Health%20and%20Medical%20Services_0.pdf (viewed 2 September 2014).

[75] International Health and Medical Services, Data on Screening Adults, HoNOS Scores, Quarter 1; Jan-March 2014, Attachment 5; Data on Screening Adults, HoNOS Scores Quarter 2, April-June 2014, Attachment 6, International Health and Medical Service, Results of mental health screenings in Australian Immigration Detention (adults), conducted Jan-Mar 2014, Second Notice to Produce, 24 September 2014.

[76] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4326.0 - National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007. At http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/ABS@.nsf/Latestproducts/4326.0Main%20Features32007?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4326.0&issue=2007&num=&view (viewed 10 October 2014).

[77] Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Detention Services Manual, Chapter 6 - Detention health - Identification & support of survivors of torture and trauma Item 17, Doc 17.2, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce 31 March 2014, p10.;Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Detention Health Framework: A policy for healthcare for people in the immigration detention system (2007) p.45

At http://www.immi.gov.au/managing-australias-borders/detention/services/detention-health-framework.pdf (viewed 10 October 2014)

[78]Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, Engaging families in the early childhood development story. At https://www.aracy.org.au/projects/engaging-families-in-the-early-childhood-development-story (viewed 2 September 2014).

[79]W Beardslee, T Solantaus, B Morgan, T Gladstone, N Kowalenko, ‘Preventive interventions for children of parents with depression: international perspectives’, The Medical Journal of Australia, MJA Open 2012; 1 Suppl 1: 23-25. At https://www.mja.com.au/open/2012/1/1/preventive-interventions-children-parents-depression-international-perspectives (viewed 2 September 2014).

[80]Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Parents and Children in Detention, Australia 2014, Responses to question: Do you think the emotional and mental health of you/your children has been affected since being in detention? Primary school aged children across the detention network, 183 respondents.

[81]Dr G Paxton, Consultant Paediatrician; Dr S Tosif, Senior Paediatric Trainee; Dr S Patel, Consultant Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation site, 7 May 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 10 September 2014).

[82]Dr G Paxton, Consultant Paediatrician; Dr S Tosif, Senior Paediatric Trainee; Dr S Patel, Consultant Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation site, 7 May 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 10 September 2014).

[83]‘Disability’ has the same meaning as in section 4 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) excluding past, future and imputed disabilities.

[84]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Attachment A – Children with disabilities, Item 2, Document 2.2, Schedule 2, Second Notice to Produce, 10 July 2014.

[85]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Attachment A – Children with disabilities, Item 2, Document 2.2, Schedule 2, Second Notice to Produce 11 July 2014.

[86]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children with mental health conditions at 10 July 2014, Item 2, Schedule 2, Second Notice to Produce 1 October 2014.

[87]Name withheld, unaccompanied child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 147 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20147%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Unaccompanied%20child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 11 September 2014).

[88]Name withheld, child who spent time in detention, Submission No 42 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%2042%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Child%20who%20lived%20in%20immigration%20detention%20previously.pdf (viewed 16 September 2014).

[89]Name withheld, unaccompanied child detained in Nauru OPC, Submission No 147 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Submission%20No%20147%20-%20Name%20withheld%20-%20Unaccompanied%20child%20detained%20in%20Nauru%20OPC.pdf (viewed 16 September 2014).

[90]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert Report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 8. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 30 September 2014).

[91]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 27. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 30 September 2014).

[92]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 27. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 30 September 2014).

[93]Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, A last resort? National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2004), p 391 (Section 9.3). At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/last-resort-national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention (viewed 30 September 2014).

[94]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 10. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expert%20Report%20-%20Dr%20Mares%20-%20Christmas%20Island%20March%202014_0.doc (viewed 30 September 2014); Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, Expert Report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 8. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 30 September 2014).