6 Mothers and babies in detention

- 6.1 Responsive and sensitive parenting

- 6.2 Pregnant women in Australian detention centres

- 6.3 Pregnancies on Nauru

- 6.4 Babies with no nationality

- 6.5 Miscarriages, deaths and terminations

- 6.6 Family separation

- 6.7 Mental health disorders in new mothers

- 6.8 Parent disempowerment

- 6.9 Motor, sensory and language development in babies

- 6.10 Adequate nutrition and healthcare

- 6.11 Protection from physical danger

- 6.12 July 2014 unrest at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island

- 6.13 Findings specific to mothers and babies

Nothing, not even the birth of my child can make me feel happy. I don’t know what family means. I haven’t been able to form a bond since the birth of my two month old daughter because of how I feel being in detention...No one can understand – you have to see what it’s like here, even for just one hour...be thankful you have your home.

(Mother of a 2 month old baby, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

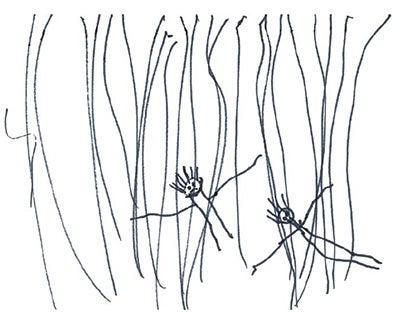

Drawing by preschool age girl, detained 420 days, Christmas Island, 2014

The early years of a child’s life provide the foundation for mental, physical and emotional health and wellbeing.[156] The World Bank Early Childhood Framework sets out some key requirements for children under the age of 2 years. These include:

- responsive and sensitive parenting

- appropriate motor, sensory and language stimulation

- adequate nutrition and health care

- protection from physical danger.[157]

This chapter reports on the impacts of the detention environment on the physical and emotional health and wellbeing of children under the age of 2 years through the four domains set out by the World Bank. The chapter concludes with a description of a serious self-harm event involving mothers and babies on Christmas Island in July 2014.

In March 2014 there were 153 children under the age of 2 years living in immigration detention across the Australian mainland and on Christmas Island.[158] On average, babies under the age of 1 had been detained for 118 days and children aged between 1 and 2 years had been detained for 226 days.[159] From the period January 2013 to March 2014, 128 babies were born into detention.[160]

6.1 Responsive and sensitive parenting

The initial attachment that a baby has with parents or caregivers provides them with a secure base for exploration and learning.[161] If the caregiver has a mental illness or is severely distressed, it is more difficult to see and provide for the child’s emotional and physical needs.[162] This may impact on the child’s social, emotional, cognitive and language development.[163]

Due to my mental state, I feel that my baby is being neglected.

(Mother of baby, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

I cannot tolerate this environment. I was given Diazepam to help with sleep but I don’t want to take the drug as it affects my ability to feed my baby.

(Mother of a 6 month old baby, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

At the second public hearing, Professor of Developmental Psychiatry, Dr Louise Newman made the following observation about babies and their ability to bond with parents:

The very young children are more likely ... [to] have attachment difficulties. We saw young children in detention environments with very poor relationships with their parents who are distressed, depressed, unable to interact with the children in the way they normally would. So in that case children develop what we would call an indiscriminate attachment, trying to have attachments with anyone.[164]

Parents of infant children were asked how often they felt sad as part of the Inquiry questionnaire. A majority of parents (65 percent) reported that they felt sad ‘most of the time’ or ‘all of the time’. Chart 23 shows the responses of 103 parents of infants under 2 to this question.

Chart 23: Responses by parents with children under the age of 2 to the question: How often do you feel sad?

Chart 23 description: How often do you feel sad? All of the time 37%, Most of the time 28%, Some of the time 26%, None of the time 1%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 103 respondents

Elizabeth Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health accompanied the Inquiry team to Christmas Island in July 2014. She reported:

The mask and gag of the profound depression we saw in so many desperate young mothers will disrupt the mother-child bond, with lasting adverse impacts on development and mental health of their children.[165]

6.2 Pregnant women in Australian detention centres

Pregnant women and women who have recently given birth are especially vulnerable to their physical and emotional environment.[166] The detention environment can be very difficult for pregnant women and new mothers as birthing often occurs in isolation from familiar people, with limited access to interpreters.[167]

The Inquiry received evidence from various sources regarding mental ill-health and post-natal depression amongst mothers who had given birth in detention:[168]

... many [mothers] showed a decrease in self-care, a wooden facial expression and slowed movements. Typical of severe depression, some mothers were observed to be unresponsive to increasingly distressed babies. This is a red flag warning for later infant’s psychosocial and developmental difficulties unless the mother is helped.[169]

Guy Coffey, a Clinical Psychologist with extensive experience in detention environments described the traumatic histories of some pregnant women in detention:

Some expectant mothers have very significant trauma histories which predispose them to post natal psychological complications. For example one pregnant woman had lost an infant at sea; another had a history of political persecution which included rape, the kidnapping of siblings, and ongoing death threats and intimidation by government authorities.[170]

Pregnant women and their partners told the Inquiry staff that they were having many difficulties in the detention environment.

They gave her antidepressant[s] even though she is pregnant. Then they said, ‘just go back then if you don’t like it’.

(Husband of pregnant woman, Christmas Island Detention Centre, March 2014)

It is very difficult to be pregnant here ... I am not happy to be pregnant here.

(Pregnant mother of two children, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

Dr Sarah Mares, Child and Family Psychiatrist described the limited support for pregnant women and the difficulties in caring for a baby at Christmas Island in her report to the Inquiry:

The harsh, hot and public environment in detention with limited antenatal care, limited neonatal and paediatric expertise, limited facilities or supports for infant care and no choice about diet and exercise, contribute to high levels of anxiety and depression. This in turn makes caring for a new baby very difficult and can reduce maternal emotional availability and sensitivity, increasing the developmental risks for the baby.[171]

6.3 Pregnancies on Nauru

Evidence to this Inquiry shows a pattern of fear amongst pregnant women about the conditions of detention on Nauru.[172] Dr Sue Packer, a Paediatrician who accompanied the Inquiry team to Inverbrackie Detention Centre, reported that parents of newborns were terrified of being taken to Nauru and that they particularly feared for their babies there.[173]

The Inquiry team spoke to the parents of a 2 month old baby at the Melbourne Detention Centre who had spent five months detained on Nauru before being transferred to the mainland for the birth of their baby. The mother described the difficulties of being pregnant and having to line up for showers on Nauru and living in tents. She claimed she was suicidal on Nauru and since the birth of her baby in Melbourne she had hardly left her room. The mother explained that she was constantly fearful of being returned to Nauru and that Serco officers had threatened to separate her from her baby with the words: ‘Not getting out of the room won’t stop you from going back to Nauru’.[174]

Clinical Psychologist, Guy Coffey, confirms the difficulties of detention on Nauru for pregnant women and new mothers:

The mothers I have spoken with regard a return to Nauru as unconscionable. Their views are of course informed by their recent experience ... there appears to be a high incidence of post-natal depression in women who have been transferred from Nauru to the mainland for the birth of their infant and ... this requires further investigation.[175]

Dr Sanggaran, a General Practitioner who had previously worked at Christmas Island, gave evidence to the Inquiry about a pregnant woman being sent to Nauru:

So this is the lady who came to Christmas Island and due to the lack of capabilities in terms of antenatal care we were unable to determine whether or not she had twins. She believed that she had twins and thinking that she did have twins she was sent to Nauru. In the context of a conversation with the medical director about the capabilities of Nauru, the discussion progressed and I was told that she was sent to Nauru as an ‘example’ of how this was to show that even [though] you’re pregnant with twins there will be no advantage and you [will] still be sent to Nauru.[176]

6.4 Babies with no nationality

Since 1 October 2013, at least 12 babies have been born in detention to mothers who have no recorded nationality.[177] These mothers are generally of Rohingya ethnic origin and come from Myanmar where they have no status as citizens and are not recorded in the census.[178]

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Australia has obligations to newborns. Article 7 requires that newborns:

shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and, as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents.

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Australia is obliged to ensure the rights of children to a nationality ‘where the child would otherwise be stateless’.[179]

Australia has addressed this obligation through section 21(8) of the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (Cth) which provides that people born in Australia who would otherwise be stateless are eligible to become Australian citizens. Children who are born in Australia to stateless asylum seekers can apply for Australian citizenship.[180]

The Federal Circuit Court has recently held that a baby born in Australia to stateless asylum seeker parents was an ‘unauthorised maritime arrival’.[181] If a person is an unauthorised maritime arrival, an officer must take the child to a regional processing country as soon as reasonably practicable.[182]

The lawyers for the plaintiff in the Federal Circuit Court case have indicated that they intend to appeal. There are also two Bills currently before Parliament that propose to deal with the status of babies born in Australia of asylum seeker parents in different ways.

The Migration Amendment (Protecting Babies Born in Australia) Bill 2014 (Cth), a private members bill introduced by Greens Senator Hanson-Young, proposes that any children born in Australia not be considered to be unauthorised maritime arrivals.

The Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Bill 2014 (Cth), introduced by the Government, proposes that children born in Australia to unauthorised maritime arrivals be considered to be unauthorised maritime arrivals.

6.5 Miscarriages, deaths and terminations

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection advised that for the period 1 January 2013 until 31 March 2014, there were 19 reported miscarriages in detention centres.[183]

Between 1 January 2013 and 31 March 2014, eight detainees died in immigration detention facilities; seven adults and one baby. The baby died at Royal Darwin Hospital on 15 October 2013.[184]

The Commission requested information about pregnancy terminations but was advised by the Department that this information is not available.

In a submission to this Inquiry, the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre reported on requests for pregnancy terminations from women living in the Nauru Detention Centre.

... three women who have terminated their pregnancy because they believed that their babies would die in detention ... these are often first babies for the couples and the mothers have told me that the conditions on Nauru are so harsh that they do not believe their babies would survive. These women report hours in queues for meals, medication, showers, toilets and clothing. They are exhausted from these days of standing in queues.[185]

A further submission from a child’s rights NGO, ChilOut, provided information about requests for terminations from women on Nauru.

...at least four requests and that two terminations (at least) have been carried out – all four families were transferred from Nauru to the Australian mainland. In all cases, the motivating factor for exploring the termination option has been that the family cannot perceive how they can raise a baby on Nauru ... Women (not just these four) are fearful of their health whilst pregnant detained on Nauru, they are terrified of giving birth on Nauru and extremely worried about the health impacts the environment may have on a newborn child. In all four cases, the women have expressed that if it were not for their immigration detention on Nauru, they would very much want to have these babies.[186]

6.6 Family separation

Pregnant women held offshore on Nauru and women held on Christmas Island are transferred to mainland Australia when they are 34 weeks pregnant.[187] The Inquiry received evidence that this process has regularly resulted in separation of mothers from partners and children and that these separations are extremely distressing and have impacts on child-parent relationships.[188]

Clinical Psychologist, Guy Coffey, reported on these separations of families on Nauru:

A number of mentally unwell pregnant mothers transferred from Nauru waiting between a week and a month to be joined by their husbands... found the separation distressing and did not understand why it needed to occur.[189]

One father of a 6 month old baby and a 5 year old boy at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, explained that his wife had been transferred alone to Darwin to give birth to their daughter. After one month the family was reunited in Darwin. The father said that for some time during the separation, his son hated his mother as he thought she had abandoned him. The father explained that his son has serious mental health issues. The boy was abducted in Iran and this trauma was compounded when he was separated from his mother for the birth of his sister. The mother was under 24 hour surveillance for self-harm or suicide risk when the Inquiry team visited her at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, in July 2014.[190]

The Australian Red Cross reports provided to the Inquiry by the Department for the period from 1 July 2013 to 31 May 2014 contain accounts of 15 pregnant women (or their partners) separated from their families either during pregnancy or when they had been transferred to give birth.[191]

In its submission to this Inquiry, the Forum of Australian Services for Survivors of Torture and Trauma reported on the impact of family separation at the time that the mother gives birth:

A mother in detention was flown to Darwin to give birth to her baby, being separated from her husband and 4 year old daughter who had to stay behind on Christmas Island. She found the birth traumatic as a result of her husband and child not being allowed to be with her. Her husband was only flown to Darwin 3-4 after the baby was born, and the mother feels that the father missed out on the opportunity to bond with his newborn son.[192]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection reported that there are policies to ensure that nuclear family members remain together wherever possible, including when pregnant women are transferred to the mainland for medical assessment or birth.[193] However the Department acknowledged:

... on some occasions in the past, there were temporary separations of family when medical assessment or treatment have been sought for one member in a different location.[194]

In May 2014 the Department advised that the policy and practice of keeping members of nuclear families together had recently been reinforced and strengthened.[195]

In instances where families or individuals are moved between detention centres, it is usually without notice. The approach to notifying detainees about when and where they will be transferred is a source of both anxiety and uncertainty. According to the International Health and Medical Service staff, it is against policy to notify people of the intent to transfer them to the mainland for ‘security reasons’. On the day of transfer, often in the early morning, ‘clients are notified and extracted from their accommodation’.[196]

6.7 Mental health disorders in new mothers

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection advised that, from the period 1 January 2013 until 10 July 2014, 18 mothers were diagnosed with mental illnesses after giving birth, including four mothers who were diagnosed with post-natal depression and subsequently hospitalised.[197] This constitutes mental illness rates of approximately 14 percent amongst new mothers in detention.

The Department submits that this rate is in line with the prevalence of post-natal depression in the Australian community as per the survey conducted by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in 2012.

A regular visitor to the Melbourne Detention Centre from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre reported:

Of the nine new mothers and babies at the MITA [Melbourne Detention Centre], five have been or are currently admitted to Mother Baby hospital units in Melbourne because of severe post natal depression. The mothers anguish over their babies but are unable to lift themselves out of the deep depression. Their husbands express utter helplessness and some are now 24 hour carers for their wives refusing to leave them alone for fear that they will harm themselves ... Detention is breaking families.[198]

6.8 Parent disempowerment

Although the Department acknowledges the importance of parents maintaining the role as decision makers and care providers for their children, evidence to this Inquiry indicates that the detention environment has a negative impact on the ability of parents to assume the parental role.[199]

Having to ask for everything, like nappies and things for my baby affects my ability to parent.

(Mother with baby, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

We missed our [medical] appointment by fifteen minutes due to changing a nappy and could not reschedule.

(Mother of 2 month old, Melbourne Detention Centre, 7 May 2014)

Dr Jon Jureidini, Child Psychiatrist who accompanied the Inquiry team to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre in Adelaide, reported that the detention environment can be a reminder to parents that they have failed their children:

A primary function of a parenting relationship is to protect a child from harm and parents in immigration detention are repeatedly being reminded of their failure to do that.[200]

When responding to the Inquiry questionnaire, 39 percent of parents with infants identified that they felt hopeless ‘most of the time’ or ‘all of the time’. Their responses are at Chart 24.

Chart 24: Responses of parents with children under the age of two to the question: How often do you feel hopeless?

Chart 24 description: How often do you feel hopeless? All of the time 31%, Most of the time 8%, Some of the time 38%, A little of the time 13%, None of the time 11%.

Australian Human Rights Commission, Inquiry Questionnaire for Children and Parents in Detention, Australia, 2014, 85 respondents

Parents are less likely to ask for help or to present at the clinic when they feel depressed, disempowered or guilty.[201]

(Dr Mares, child and family psychiatrist, Christmas Island detention centres, March 2014)

Dr Nick Kowalenko, Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, who assisted the Inquiry team on a visit to the Sydney Detention Centre reported on the restrictions to parenting:

Parents complained that in their parenting roles their independence about making parenting decisions was consistently compromised and their autonomy to make decisions about their children and implement them was severely restricted. Parents complained that arbitrary limits to their decision making about acting in the best interests of their children persisted, and described feeling powerless in their role as parents.[202]

Professor Elizabeth Elliott spoke about the distress of parents at Christmas Island with an infant who had a facial abscess that required surgical drainage. This family had no idea when their child would be treated.[203]

... the parents grew increasingly anxious over the several days of our visit. Although they had seen the paediatrician, they had been given no indication of transfer and approached us with their concern. When we questioned IHMS and immigration staff we were told the child was to be transferred to Perth the next day for surgery, but that they were not at liberty to inform the family in advance.[204]

During the March 2014 visit to the Christmas Island detention centres, parents of babies reported having to line up to get their daily allocation of three nappies, three baby wipes and three scoops of formula.[205] If they required more than this ration, which was likely, they needed to line up again. They would queue for long periods in extreme heat or torrential rain and often holding a newborn baby.[206]

The Commission acknowledges that this practice has changed since the Inquiry commenced. Nappies are currently distributed by sealed packs of eight, 10 or 12, depending on the infant’s size.[207]

In a submission to the Inquiry, a health professional who had worked on Christmas Island reported that limited clothes were available for babies and that mothers were constantly washing in order to keep their babies clean.[208]

One mother at Inverbrackie Detention Centre in Adelaide reported that she was told by detention staff that babies would need to ‘wear out’ their clothes before they would be replaced.[209] Another mother reported that she could not get additional socks for her toddler, even though her toddler frequently got her feet wet and needed to change them.[210]

One of the things that would touch me is that it was so often to see that one [of] the child’s first words spoken would be ‘officer’.[211]

(Professional working at the Christmas Island detention centres, May 2014)

6.9 Motor, sensory and language development in babies

States must recognise the right of the child to engage in age appropriate play and recreational activities. (Article 31 Convention on the Rights of the Child)

He is [18 months old] and he refuses to eat anything except milk. His sleep is very poor. 15 times a night he wakes and cries. He hasn’t started to talk yet.[212]

(Parent of 18 month old child, Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 2 March 2014)

During the March 2014 visit to the Christmas Island detention centres, the Inquiry team was informed that a Mothers’ Group is run each month by International Health and Medical Services. Issues discussed at this group include the lack of appropriate surfaces for young children to crawl and fear of children getting splinters.[213]

Dr Sarah Mares observed a level of disengagement amongst parents and little expectation that their attendance at groups such as Mothers’ Group will be worthwhile.[214]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection advised in July 2014 that a crèche and play centre had been established with classes underway at the Christmas Island detention centres.[215] During the July 2014 visit, the Inquiry team observed these facilities - a newly decorated play room with air-conditioning and new toys at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island. The Inquiry team was advised that the space was for women with young children to take their children to play. Access to the crèche was on a limited and rostered basis, being for an hour each day.[216]

Other improvements at Christmas Island included a shade cloth over one outdoor playground and the construction of a new playground at Phosphate Hill Detention Centre.

Prior to the upgrade, Dr Sarah Mares observed in March 2014 that there were ‘very few toys and few books in languages that parents can read to their children’ at Christmas Island.[217]

At the Inverbrackie Detention Centre in South Australia, early childhood classes are available to babies and their parents each morning. In addition, smaller ‘attachment’ groups for the very depressed mothers and their babies take place each afternoon.[218] Regardless of these opportunities, paediatrician Dr Sue Packer, observed that:

Without exception, every adult, young person and older child I saw was distressed, with a feeling of deep hopelessness – perhaps a little hope as they came willingly to see us – and they conveyed that they were in despair, with absolutely no control over their lives and all anticipated being sent offshore with their infants and little children.[219]

A representative from child’s rights NGO ChilOut, Ms Sophie Peer reported at the second public hearing:

Some may argue that the right to play exists in detention but ... [i]s it play if there’s a toy library that is six metres by 2.4 metres and open for two hours a day and you can’t borrow the toy? Is it play if your parents are too traumatised to sit and do a puzzle with you?[220]

Medical professionals observed that the physical environment at Christmas Island was not a place where babies could learn to walk or crawl:

The Aqua and Lilac Detention Centres on Christmas Island were all concrete and stone and unsuitable for babies to crawl.[221]

(Paediatrician, Associate Professor Zwi, describing the facilities within the Aqua and Lilac Detention Centres, Christmas Island, 4 April 2014)

The accommodation in the Christmas Island detention facilities is incredibly cramped. Often there is a bunk bed and then if you have a cot beside that bed, and put in there a small cupboard and a small fridge, then there’s very little space for a child to walk around or play. Perhaps a metre squared, which is totally unsatisfactory for children who are in developmental phases.[222]

(Paediatrician, Professor Elliott, describing Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, July 2014)

The physical space is harsh and uninviting to exploration.[223]

(Child and Family Psychiatrist, Dr Mares, describing the Christmas Island detention centres, March 2014)

6.10 Adequate nutrition and healthcare

States must recognise the right of the child to the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. (Article 24 Convention on the Rights of the Child)

States must take appropriate measures to ensure appropriate pre-natal and post-natal health care for mothers (Article 27 (2)(d) Convention on the Rights of the Child)

A baby’s development begins before birth. Appropriate antenatal care and adequate support for pregnant women is vital to the health and wellbeing of the developing baby.[224]

The purpose and importance of antenatal care was detailed by specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist Professor Caroline de Costa, at the second public hearing:

[T]here [are] really two main purposes with antenatal care. There’s medical care, specifically medical care and obstetric care but there is also a very large social and family and mental health element because we want to have an outcome where the baby goes home to the best possible social and family circumstances. The same is true of the mother so mental issues are very, very important in antenatal care.[225]

The paediatricians and child psychiatrist accompanying the Inquiry team to Melbourne Detention Centre in May 2014 observed that the antenatal appointments and screening appeared to be appropriate, but noted that women described the environment as a difficult place to be pregnant.[226]

In November 2013 a group of 15 doctors working at the Christmas Island detention centres sent a letter of concern (‘the doctors’ letter of concern’) to detention medical provider, International Health and Medical Services. The letter outlined concerns about the standard of medical care and practice at the Christmas Island detention centres.[227] The doctors reported that the antenatal care was far below any accepted Australian standard and could potentially put pregnant women and their babies at unnecessary risk of harm.[228]

In its submission to the Inquiry, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians detailed concern about insufficient resources on Christmas Island and Nauru to adequately monitor the developing baby in utero. This monitoring was only available once pregnant women were transferred to the mainland.[229]

At the second public hearing, Professor Caroline de Costa detailed instances where receiving hospitals on the mainland were not informed of the impending arrival of pregnant women.[230] This resulted in women arriving at hospital unannounced and in labour. Some of these women were without medical records and without interpreters.[231]

When they took me to hospital for an ultrasound, and when I was hospitalised for three days, I didn’t have [an] interpreter.

(Pregnant woman, Blaydin Detention Centre, Darwin, 12 April 2014)

The Inquiry heard evidence that at least two women had been transferred from Christmas Island to Darwin to give birth without their partner and without an interpreter. In one instance, a woman could not understand why she was having a caesarean section.[232]

In July 2014, a mother of an 11 month old boy on Christmas Island spoke about her experience of having her son. The woman said that she and her husband were transferred from Christmas Island to Darwin in preparation for the birth. When the woman left to go to the hospital, her husband was not allowed to accompany her in the ambulance. Although she did go into labour naturally, the woman was told that she had to have a caesarean. She explained that there was no interpreter present when she signed the consent form for the procedure. She said that there was a Serco officer outside her hospital room at all times.[233]

The provision of services and resources to mothers and newborns differs across the detention system. For example, while parents detained at Inverbrackie Detention Centre were generally happy with the support for their babies, parents at the Christmas Island detention centres voiced concerns.[234]

Mothers at Christmas Island reported that sometimes the baby food was out of date. One mother said:

Many mums can’t read but when I showed immigration that they had given me expired baby food they took it but said nothing.[235]

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians outlined the impact of inadequate services on babies and infants in a submission to this Inquiry:

... lack of access to appropriate weaning foods and lack of flexibility with infant and toddler meals may result in young children failing to thrive and developing nutritional deficiencies.[236]

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has published Guidelines for preventative activities in general practice. These Guidelines set out standards for assessing developmental progress, including vision and hearing, at the ages of two, four and six months of age.[237]

The Christmas Island doctors’ letter of concern reported that the medical care for babies was inadequate and that there was no regular monitoring of child health. [238]

The doctors’ letter also asserts that in November 2013 there was no reliable test of growth, development, visual acuity or hearing for children at the Christmas Island detention centres:

Physical growth and development also remains unmonitored. Children with failure to thrive are easily missed with no established protocols for regular monitoring of physical development. In fact, none of the scheduled physical and developmental assessments that would normally occur in the community ... occur at [the] Christmas Island [detention centres]. [239]

Dr Sarah Mares observed that at the Christmas Island detention centres:

[International Health and Medical Services] did not complete any regular or standardized developmental assessments or keep growth charts. We were told that daily health and weight checks are done on infants and that there is a “project” to set up a regular 12 month developmental assessment.[240]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection provided the following statistics for the completion rate of routine health checks for babies detained at the Christmas Island detention centres as at 19 March 2014:

- six week check: 19 of 33 babies (58 percent)

- six to nine month check: 11 of 24 babies (46 percent)

- 18 to 24 month check: 29 of 76 babies (38 percent).[241]

While not all babies had received health checks in March 2014, there is evidence that the services are improving on Christmas Island. The Department advised that as at May 2014, all development checks for children detained at the Christmas Island detention centres had been completed.[242]

An International Health and Medical Services letter to the Commission in September 2014 confirmed improvements in medical services on Christmas Island, reporting that all children in detention are up to date with their checks and vaccinations as per the community schedule.[243]

6.11 Protection from physical danger

At the Christmas Island detention centres, various environmental risks exist for babies and infants. Professor Elizabeth Elliott reported:

Young children are vulnerable to a range of infectious diseases and in these overcrowded conditions infections spread quickly. We witnessed many children with respiratory infections (including bronchiolitis in infants, probably due to respiratory syncytial virus) and there had been outbreaks of gastroenteritis.

We repeatedly heard the refrain ‘my kids are always sick.’ ... Asthma is common in childhood and was a frequent diagnosis in the camps. This is not surprising as respiratory infection is the most common reason for exacerbation of asthma. Parents expressed concern that ... onset of asthma may relate to the environment.[244]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection states that there is a lower rate of respiratory illness presented by children in detention when compared to those in the Australian community. The Department notes that though viral illnesses do appear, respiratory conditions requiring antibiotics are infrequent. The Department states that as at 15 October 2014, three children under the age of 16 have asthma out of a group of 107. (Note: viral respiratory infections are not treated with antibiotics).

Mothers at Christmas Island reported concerns at not having cots for their babies. They were worried about sleeping with their babies and they were concerned for the safety of their babies including the risk of them rolling off beds.[245]

The National Association for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect reported that in Darwin there were insufficient cots during times of overcrowding. This resulted in ‘babies having to sleep with their mothers, causing distress to parents [who were] concerned about accidentally injuring their child’.[246]

At Christmas Island small children can crawl under the ‘containerised accommodation’ because there are no barriers to prevent access. Dr Mares reported:

The physical space is ... at times unsafe, for example puddles of water and unfenced areas under “donga” accommodation.[247]

In a submission to this Inquiry, a child rights NGO, ChilOut expressed concern about the ability of parents to safely wash their newborn babies:

There are no baby baths on CI [Christmas Island], women are standing in these dirty shower areas and holding their 28 day-old babies under the water.[248]

6.12 July 2014 unrest at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island

In mid-July 2014, the Inquiry team became aware of reports regarding unrest and self-harm incidents by mothers of babies at Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island.[249] News about the protest on Christmas Island came through emails and messages to the Commission:

today 8 women who that how babys they cut them self in bad way and everybody start to broking every the in the camp and now we how big officers from single comp and we cannot move because they will fight with us

pleas helpp us

i'm scard(Email from Construction Camp Detention Centre, Christmas Island, 8 July 2014)

The Inquiry team returned to Christmas Island on 15 July 2014 and spoke with mothers, staff members and witnesses to the unrest.

The head of the medical team advised the President of the Commission that the incidents of self-harm had increased in the three months leading up to July 2014. Numbers of people on self-harm and suicide watch had risen from two to 14 people in recent months.[250] Many families were coming up to the one year anniversary of their time in detention and tensions were heightened.

Dr Sarah Mares described Construction Camp as a harsh and cramped environment for parents and babies with a hard and stony ground and very little grass.[251] A volunteer at the Christmas Island detention centres described the environment in the following terms:

[It] puts children directly in the path of harm. The family compound on Christmas Island is bordered with jungle and there was a constant scuttling of giant centipedes around the pathways. Red crabs would enter both the compounds and the individual rooms. They have claws strong enough to remove a human toe with ease. Children taking their first steps at 12 months of age would be wandering past these creatures daily.[252]

A medical doctor who had worked on Christmas Island in 2013 reported at the third Inquiry public hearing:

The ground is phosphate, rock and dust. It was very unsuitable for kids to crawl or learn how to walk on and was [a] very tough surface to fall on.[253]

Residents of Construction Camp reported the following sequence of events about the self-harm and suicide attempts.[254]

On Friday 4 July 2014, mothers of babies born in Australia staged a peaceful protest for better facilities for their babies. The mothers were concerned that the conditions at Construction Camp were detrimental to their babies’ development. They requested that they be transferred to the mainland with their families, pending the court decision regarding the rights of babies of asylum seekers born in Australia.[255]

Immigration officials agreed to meet with the mothers on Monday 7 July 2014. At the meeting mothers were informed that they would not be relocated to mainland Australia due to their arrival in Australia after 19 July 2013. They were told: ‘you will never be settled in Australia. You will be going to Nauru or Manus Island and that’s the end of the story’.[256]

In response to the message, it was reported that parents started screaming and shouting and threatening to set the camp on fire.[257] According to the adults interviewed at Construction Camp, the ‘big guards’ arrived in response to the protest. These were Serco officers from the single male camp. Adults living in Construction Camp told the Inquiry team that the officers were threatening to hit people. Police were also seen outside Construction Camp.[258] While there were reports that mothers had broken glass and mirrors, others denied that this had occurred.[259]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection has confirmed that immediately following the unrest on 7 July 2014:

- seven individuals made threats of self-harm and four actually self-harmed

- ten mothers were placed on International Health and Medical Services’ guided supportive monitoring and engagement under the Psychological Support Program and eight of these mothers were assessed as requiring constant supervision and monitoring.[260]

The Department confirmed that on 14 July 2014 there were ten mothers on ‘guided supportive monitoring and engagement’ under the Psychological Support Program. These women were receiving constant supervision and monitoring.[261] This means 24 hour surveillance by a Serco officer.

Professor Elizabeth Elliott described the 24 hour surveillance in the following terms:

Supervision is provided by a guard ... rather than a nurse or member of the medical staff (as would occur elsewhere in Australia). This level of surveillance necessitates the door of the home to be open constantly and results in a lack of privacy, including during feeding the baby and sleeping.[262]

During the visit, the Inquiry team met with many mothers who had been involved in the unrest.

One mother of a 6 month old infant under 24 hour surveillance described how she had attempted to self-harm using a broken melamine plate.[263] She spoke to the Inquiry team while remaining in her bed - where she had been confined for days.[264]

We need somewhere for our kids to crawl. They keep repeating ‘you have to go to Nauru’ whenever we ask for anything.[265]

One mother under 24 hour surveillance commented:

I want to end of my life. We asked to be moved from here to the mainland. They said you have to go to Nauru. The room is too small, my baby wants to crawl but she can’t. It’s dirty. All the kids are sick and all the babies. Eye infections ... ear infections.[266]

One mother of an 8 month old infant under 24 hour surveillance had tried to suffocate herself using a plastic bag.[267] At the time of the Inquiry team’s visit, the mother had been bedbound for over a week.[268] Her husband commented:

She doesn’t sleep. Nothing to help her sleep – she doesn’t want to talk to anyone. Sometimes she just stares for 3 or 4 hours. She only has water...[269]

Another mother under 24 hour surveillance reported:

When I am upset I self-harm. Three days ago I was very depressed because I couldn’t breathe (from asthma), the children wouldn’t eat, the boy was coughing a lot... I hit my head on the wall. Let us out. We are tired. Our children are sick and they are getting sicker. And we are sick too.[270]

According to the husband of another mother under 24 hour surveillance, the following occurred after the unrest:

She locked the toilet door. I realised she had taken the Gillette razor and was about to cut her wrists. I hit her and she cut her arm further up instead. After that, despite the guard, she made another attempt. She broke a rigid cup and tried to harm herself. She is still on watch. She is no better. She is on no medication because she is breast feeding. They offered a tranquillizer but she is looking after a baby. That is no solution.[271]

A mother of an 11 month old baby said:

After they read me my rights again I tried to kill myself. I put a rope around my neck, but a Serco guard caught me before I could finish. He was from the single male camp and said to me ‘If you want to kill yourself I’ll tell you a better way’.[272]

Another mother said that following the protest she:

hit the glass in the window with my head. Then 3-4 Serco officers held me back, then I gourged my forearms. I have been here for year. I just asked for more space for my baby to grow.[273]

A mother of two children aged 6 and 10 months who was under surveillance had self-harmed and threatened further harm:

I will do it if my kids stay in this situation. And I already have a plan.[274]

The mother continued:

There is no space for my baby, no place to put him down. There are centipedes, insects, worms in the room. Rats run through. We have no eggs, no fruit. We get out of date food. I don’t want a visa, I just want somewhere safe and clean for my child. Serco is not sympathetic – they say just put them down. The guards said if you don’t calm down we will get the police dogs onto you.[275]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection reported to the Inquiry that there are no police dogs on Christmas Island.

A father of a 5 year old boy and 6 month old girl whose wife was under 24 hour surveillance said:

My wife has been on suicide watch for around ten days now as she has tried to commit suicide a few times. She only wants to save her children. She used to speak to her mother every day, but now she won’t go out of her room. I beg you to help her. I have lost my wife.[276]

At the fourth public hearing, in discussion regarding the unrest at the Christmas Island detention centres, counsel assisting the Inquiry put to the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection:

...do you understand Minister, why the mothers are asking to be moved to the mainland? ... [277]

Minister Morrison replied:

... for these young mothers I can understand how they might feel. I can’t specifically understand. I have not been in that situation personally but I can at least attempt to understand it and I have spoken to many, many people who are in detention over many years but at the end of the day the Government has to make assessments about the broader policy environment which I’m responsible for as Minister and I’m accountable for the results that those policy environments produce and that’s what the Government continues to remain focussed on. Now where there are medical reasons where someone might be transferred to the mainland and the Secretary will correct me if I’m wrong but I understand one of those people/persons has been transferred to the mainland and are receiving mental health support in a dedicated facility. Now that’s appropriate. There is a medical reason for the person’s transfer. But otherwise the policy is as it is and the policy’s effectiveness is maintained by its consistency. One of the reasons we had so many children in detention and why over 8,000 children got on boats is [be]cause they thought they would get what they were paying for. Now that has changed and they’re not getting on the boats anymore.[278]

6.13 Findings specific to mothers and babies

Detention impedes the capacity of mothers to form bonds with their babies.

There are unacceptable risks of harm to babies in the detention environment.

Babies born in detention in Australia to stateless parents may be sent to Nauru without any recorded nationality.

The Commonwealth has a responsibility to provide babies with a nationality when they are born to stateless parents in detention, Convention on the Rights of the Child, articles:

7(1): The child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and, as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents.

7(2): States Parties shall ensure the implementation of these rights in accordance with their national law and their obligations under the relevant international instruments in this field, in particular where the child would otherwise be stateless.

Detention impacts on the health, development and safety of babies. At various times mothers and babies in detention were not in a position to fully enjoy the following rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child:

- the right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 24(1)); and

- the right to enjoy ‘to the maximum extent possible’ the right to development (article 6(2)) and the associated right to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development (article 27(1)).

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasised that:

Among the key determinants of children’s health, nutrition and development are the realization of the mother’s right to health and the role of parents and other caregivers. (See General Comment No 15, paragraph 18)

The Committee has also recognised that ‘parenting under acute material or psychological stress or impaired mental health’ is likely to impact negatively on the wellbeing of young children (See General Comment No 7, paragraph 18).

The negative impact of detention on mothers has consequences for the health and development of their babies. For example, mothers who are distressed or depressed in the detention environment can struggle to form healthy attachments with their babies. This in turn has consequences for the social development of those babies. Also, the limits that the detention environment places on the ability of mothers to make decisions about their babies’ care can have adverse impacts on the development and health of their babies.

Babies’ right to development is also directly compromised by the physical detention environment. For example, the physical environment in the Christmas Island detention facilities does not provide safe spaces for babies to learn to crawl or walk.

- the right to be protected from all forms of physical or mental violence (article 19(1))

The self-harm and distress of mothers on Christmas Island in July 2014 created risks for their babies.

[156]United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 7 (2005): Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood, 20 September 2006, CRC/C/GC/7/Rev.1, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/460bc5a62.html (viewed 27 August 2014)

[157]The World Bank, Early Childhood Development, What is Early Childhood Development? Development Stages. At http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTCY/EXTECD/0,,contentMDK:20260280~menuPK:524346~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:344939,00.html (viewed 25 August 2014)

[158]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[159]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children average time in immigration detention 31 March 2014, Item 3, Document 3.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[160]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children born in immigration detention 31 March 2014, Item 2, Document 2.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[161]Australian Government Department of Education, National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care, Early Years Learning Framework (November 2013). At http://education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework (viewed 27 August 2014).

[162]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 21. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed on 11 August 2014).

[163]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 21. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed on 11 August 2014).

[164]Professor L Newman, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 16 September 2014).

[165]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, Children's Hospital, Westmead, Expert assisting the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Additional evidence provided to the Inquiry, Email communication, 26 September 2014.

[166] Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, Children's Hospital, Westmead, Expert assisting the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. Additional evidence provided to the Inquiry, Email communication, 26 September 2014.

[167]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 29. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[168]Professor C de Costa, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 11. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 15 September 2014); G Coffey, Submission No 213 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[169]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 20. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed on 11 August 2014).

[170]G Coffey, Submission No 213 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[171]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 29. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[172]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Supplementary Attachment, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014); Professor L Newman, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 6. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 16 September 2014).

[173]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[174]Australian Human Rights Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Inquiry team interview at Melbourne Detention Centre, File Note,7 May 2014.

[175]G Coffey, Submission No 213 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[176]Dr J-P Sanggaran, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014, p 21. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[177]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Children in detention data list as at 31 March 2014, Item 1, Document 1.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014; Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Attachment - Children born to parents in detention, Item 6, Document 6.2, Schedule 2, Second Notice to Produce, 11 July 2014.

[178]See K K Ei and M T Aung, ‘Myanmar Will Not Recognize Rohingyas on Upcoming Census’, Radio Free Asia, 13 March 2014. At http://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/census-03132014181344.html (viewed 30 September 2014).

[179]Convention on the Rights of the Child, art 7(2).

[180]See Civil Liberties Australia, Submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee Inquiry into the Migration Amendment (Protecting Babies Born in Australia) Bill 2014 (15 August 2014), pp 5-6; Refugee Council of Australia, Submission to the Senate Standing Committees on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the Migration Amendment (Protecting Babies Born in Australia) Bill 2014 (August 2014), para 3.1-3.4; M Foster, J McAdam and D Wadley, Submission to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee Inquiry into the Migration Amendment (Protecting Babies Born in Australia) Bill 2014 (29 August 2014), pp 9-10. All available at http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Protecting_Babies/Submissions (viewed 29 September 2014).

[181] Plaintiff B9/2014 v Minister for Immigration [2014] FCCA 2348.

[182] Migration Act, s 198AD(2).

[183]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Miscarriages, Supplementary Question, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[184]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Deaths, Self-harm and Incidents, Item 11, Document 11.1, Schedule 2, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[185]Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, Submission No 104 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 5. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 12 August 2014).

[186]ChilOut, Submission No 168 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Supplementary Attachment, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[187]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Submission No 45 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 48. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[188]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 13. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014); Forum of Australian Services for Survivors of Torture and Trauma, Submission No 210 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 13. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[189]G Coffey, Submission No 213 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 6. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 21 August 2014).

[190]Australian Human Rights Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Inquiry team visit to Christmas Island Detention Centres, File Note, 17 July 2014.

[191]Department of Immigration and Border Protection ,Oversight reports- Australian Red Cross, Item 2, Document 2.1, Schedule 3, Second Notice to Produce, 11 July 2014.

[192]The Forum of Australian Services for Survivors of Torture and Trauma, Submission No 210 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 13. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[193]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Submission No 45 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 40. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[194]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Submission No 45 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 40. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[195]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Family Unity, Item 6, Document 6.1, Schedule 3, First Notice to Produce, 31 March 2014.

[196]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 27. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 3 October 2014).

[197]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Data on mothers with children in detention, Item 7, Document 7.1, Schedule 2, Second Notice to Produce, 11 July 2014.

[198]Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, Submission No104 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 12 August 2014).

[199]Department of Immigration and Border Protection, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014); Forum of Australian Services for Survivors of Torture and Trauma, Submission No 210 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 12. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 20 August 2014).

[200]Dr J Jureidini, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[201]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 16. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[202]Dr N Kowalenko, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Sydney Detention Centre, 30 March 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 4 September 2014).

[203]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 27. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 3 October 2014).

[204]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 27. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 3 October 2014).

[205]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 11. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[206]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 11. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[207]K Constantinou, Assistant Secretary AHRC Inquiry Taskforce, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Correspondence to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, AHRC request for information from CI visit – DIBP response, 12 May 2014, p 13.

[208]Name withheld, Health professional, Submission No 10 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 5. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 15 August 2014).

[209]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014, p 2. At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expert%20Report%20-%20Dr%20Packer%20-%20Inverbrackie%20May%202014.docx (viewed 28 August 2014).

[210]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[211]Name withheld, Professional working in immigration detention, Submission No 84 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 12 August 2014).

[212]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 16. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[213]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 15. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[214]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 15. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[215]The Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[216]Professor E Elliott, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014, pp 2-3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[217]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 5. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[218]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 13 October 2014).

[219]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[220]S Peer, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 15 September 2014).

[221]Associate Professor K Zwi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014, p 4. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 28 August 2014).

[222]Professor E Elliott, Third Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 31 July 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[223]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 5. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[224]Dr S Mares, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 28 August 2014).

[225]S Peer, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 4. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 15 September 2014).

[226]Dr G Paxton, Consultant Paediatrician; Dr S Tosif, Senior Paediatric Trainee; Dr S Patel

Consultant Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation site, 7 May 2014, p 9. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[227]Christmas Island Medical Professionals, Letter of Concern for review by International Health and Medical Services, November 2013 (Published in full by The Guardian, 13 January 2014), p 2. At http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2014/jan/13/christmas-island-doctors-letter-of-concern-in-full (viewed 4 September 2014).

[228]Christmas Island Medical Professionals, Letter of Concern for review by International Health and Medical Services, November 2013 (Published in full by The Guardian, 13 January 2014), p 3. At http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2014/jan/13/christmas-island-doctors-letter-of-concern-in-full (viewed 4 September 2014).

[229]Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Submission No 103 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 11 August 2014).

[230]Professor C de Costa, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 7. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 15 September 2014).

[231]Professor C de Costa, Second Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Melbourne, 2 July 2014, p 7. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 15 September 2014).

[232]Dr S Mares, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 28 August 2014).

[233]Australian Human Rights Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Inquiry team visit to Christmas Island Detention Centres, File Note,17 July 2014.

[234]Dr S Packer, Community Paediatrician; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Inverbrackie Detention Centre, May 2014, p 2. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[235]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to Christmas Island Detention Centres, July 2014, p 11. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 8 October 2014).

[236]Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Submission No 103 to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 11 August 2014).

[237]Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Preventive activities in children and young people, http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/redbook/preventive-activities-in-children-and-young-people/#86 (viewed 4 September 2014).

[238]Christmas Island Medical Professionals, Letter of Concern for review by International Health and Medical Services, November 2013 (Published in full by The Guardian, 13 January 2014), p 51. At http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2014/jan/13/christmas-island-doctors-letter-of-concern-in-full (viewed 4 September 2014).

[239]Christmas Island Medical Professionals, Letter of Concern for review by International Health and Medical Services, November 2013 (Published in full by The Guardian, 13 January 2014), p 51. At http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2014/jan/13/christmas-island-doctors-letter-of-concern-in-full (viewed 4 September 2014).

[240]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 9. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[241]K Constantinou, Assistant Secretary AHRC Inquiry Taskforce, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Correspondence to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, 12 May 2014.

[242]K Constantinou, Assistant Secretary AHRC Inquiry Taskforce, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Correspondence to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, 12 May 2014.

[243]M Parrish, Regional Medical Director, International Health and Medical Services, Correspondence to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, 19 September 2014.

[244]Professor E Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health; Expert Report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, July 2014, p 10. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 8 October 2014).

[245]Associate Professor K Zwi, First Public Hearing of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, Sydney, 4 April 2014, p 4. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-1 (viewed 28 August 2014).

[246]The National Association for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, Submission No 153 to the Australian Human Rights National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed 15 August 2014).

[247]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 5. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).

[248]ChilOut Submission No 168 to the Australian Human Rights National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, p 30. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014-0 (viewed on 11 August 2014).

[249]Anonymous correspondence emailed to the Commission, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014, 8 July 2014; Refugee Action Coalition, ‘Mothers attempt suicide as conditions deteriorate on Christmas Island’ (Media Release, 8 July 2014). At http://www.refugeeaction.org.au/?p=3362 (viewed 10 September 2014); ABC News Radio, ‘Nine asylum seeker women threatened suicide, says Island Shire president’ (News Report, 9 July 2014). At http://www.abc.net.au/pm/content/2014/s4042716.htm?site=perth (viewed 10 September 2014).

[250]T Voss, Entry meeting of Australian Human Rights Commission Inquiry visit, Phosphate Hill Camp, Christmas Island, File note, 15 July 2014.

[251]Dr S Mares, Child Psychiatrist; Expert report to the Australian Human Rights Commission after the visit to the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centres, March 2014, p 3. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/expert (viewed 28 August 2014).