Chapter 2: Results of the National Prevalence Survey

In summary

Mothers Survey

- Discrimination in the workplace against mothers is pervasive. One in two mothers reported experiencing discrimination at some point during pregnancy, parental leave or on return to work.

- Discrimination is experienced in many different forms ranging from negative attitudes in the workplace through to job loss.

- 32% of all mothers who were discriminated against at some point went to look for another job or resigned.

- One in five (18%) mothers reported that they were made redundant, restructured, dismissed or their contract was not renewed either during their pregnancy, when they requested or took parental leave or when they returned to work.

- Discrimination has a significant negative impact on mothers’ health, finances, career and job opportunities and family. 84% of mothers who experienced discrimination reported a negative impact as a result of that discrimination.

- Discrimination has a negative impact on women’s engagement in the workforce and their attachment to their workplace. Many mothers reported that they resigned as a result of the discrimination or looked for another job. Mothers who experienced discrimination during pregnancy were less likely to return to their job or return to the workforce.

- 91% of mothers who experience discrimination do not make a formal complaint (either within their organisation or to a government agency).

- Several characteristics of the individual, their employment and the workplace, impacted on mothers experience of discrimination. For example, young mothers and single mothers are more likely to experience discrimination during pregnancy.

- There is limited awareness and understanding of discrimination, its nature and consequences amongst mothers.

Fathers and Partners Survey

- Despite taking very short periods of parental leave, fathers and partners face discrimination. Over a quarter (27%) of survey respondents reported experiencing discrimination when requesting or taking parental leave or when they returned to work.

- Fathers and partners experience discrimination in many forms and experience significant impacts as a result of discrimination.

- Very few fathers and partners make a formal complaint in response to the discrimination.

- There is limited awareness and understanding of discrimination, its nature and consequences amongst fathers and supporting partners.

As part of the National Review, the Commission contracted Roy Morgan Research to conduct a National Survey to measure the prevalence of discrimination in the workplace related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work following parental leave.

This survey provides baseline data on the extent, nature and consequences of discrimination against employees in Australian workplaces related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work following parental leave.

It is the first nationally representative survey of women’s perceived experiences of discrimination in the workplace as a result of their:

- pregnancy

- request for or taking of parental leave

- return to work following parental leave.

It also offers a case study of the extent and nature of discrimination experienced by fathers and partners that have taken time off work to care for their child under the ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ scheme (ie 2 weeks at the minimum wage within 12 months of birth/adoption of the child).

Similar surveys have only been conducted in a small number of countries, such as the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The survey results create a benchmark for:

- measuring progress in eradicating discrimination in the workplace related to pregnancy, breastfeeding, and family responsibilities

- mapping trends over time.

This chapter details the findings and analyses it in relation to the following key areas:

- prevalence of discrimination

- type of discrimination

- impact of discrimination

- response to discrimination

- characteristics of the individual, their employment and their workplace

- understanding of discrimination

- sources of information

- issues related to leave and return to work.

2.1 Methodology

Two separate surveys were conducted – the ‘Mothers Survey’ and the ‘Fathers and Partners Survey’.

Respondents were interviewed by telephone (computer assisted telephone interview, CATI). The samples for each survey were drawn from Department of Social Services (DSS) databases of recipients of parental payments. As a result of the introduction of the ‘Paid Parental Leave’ and ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ schemes, there is greater access to databases of mothers, fathers and partners in Australia.

(e) Mothers Survey

The Mothers Survey measured the experiences of discrimination of birth and adoptive mothers[53] in the workplace at three points in time:

- during pregnancy

- when requesting or during parental leave

- upon return to work following parental leave (including discrimination related to family responsibilities and breastfeeding or expressing milk).

The survey was developed in collaboration with Roy Morgan Research and academics working in this field in Australia.[54] It also draws from similar surveys conducted in the United Kingdom[55] and Ireland,[56] as well as relevant Australian surveys.[57] The survey questionnaire is included in Appendix B.1.

Existing qualitative and quantitative data on the nature of discrimination in Australian workplaces related to pregnancy/return to work after parental leave was drawn on to inform the content and structure of the questionnaire. The National Review Reference Group[58] also contributed to the development of the survey.

Mothers Survey Sample

Respondents to the Mothers Survey (n=2002) were randomly drawn from a DSS database of women who were recipients of either:

- Paid Parental Leave (PPL) in the four month period of July/August and October/November 2011, or

- the Baby Bonus (BB) in the five month period of May, July/August, October/November 2011.

The respondents were aged between 18 and 49 years old and in the workforce as an employee at some time during their pregnancy (or while adopting a child).

In the period in which the sample was drawn (May-November 2011), 98.5% of mothers were paid either the PPL or BB.[59]

The survey was conducted approximately two years after the survey respondents accessed either the PPL scheme or received the BB.

Based on ABS data on the proportion of working mothers that take PPL or receive the BB, the total sample of mothers (n=2,002) consisted of 80% PPL recipients (n=1,602) and 20% BB recipients (n=400).[60]

Results from the Mothers Survey have been weighted to the estimated Australian population of women, who at the time of the survey, were aged between 18 and 49 years, had been employed at some time in the previous nine months as an employee and had given birth to a child in the six month period covered by the DSS sample. This was in order to remove any bias in the sample provided by the DSS in terms of age and labour force status while pregnant.[61]

As such, the results of the Mothers Survey are representative of the experience of working mothers aged 18-49 years old with a child of approximately two years of age.

(f) Fathers and Partners Survey

The Fathers and Partners Survey measured the experience of fathers and partners who had taken the new legislative entitlement of two weeks of pay (at the minimum wage) under the ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ scheme (DaPP) for leave taken to care for their child.

The Fathers and Partners Survey measured discrimination in the workplace at two points in time:

- when requesting or during parental leave

- upon return to work following parental leave (including discrimination related to family responsibilities).

The survey questionnaire was adapted from the survey used for the Mothers Survey. While there was no other comparable survey of the experiences of fathers and partners upon which to draw, existing qualitative data on fathers’ and partners’ experiences of discrimination in Australian workplaces related to parental leave and return to work after parental leave was used to inform content and structure of the questionnaire. The National Review Reference Group[62] also contributed to the development of the survey. The survey questionnaire is included in Appendix B.2.

Fathers and Partners Survey Sample

Respondents to the Fathers and Partners Survey (n=1001) were randomly drawn from a database of DaPP recipients provided by the DSS. As this scheme has only been in place since 1 January 2013, the survey was based on the experiences of fathers and partners who:

- had a baby/adopted a child in the period February to April 2013

- were aged between 18 and 49 years old

- were in the workforce as an employee just before the birth/adoption of their child.

This sample is representative of the experiences of these ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ scheme recipients. However, as only a small proportion of new fathers and partners access the DaPP scheme,[63] it is not representative of all working fathers and partners who have had a child.

Given the results of the Fathers and Partners Survey are not representative of all new father and partners and that respondents to this survey had a baby/adopted a child within a different timeframe to the mothers interviewed, the results cannot be compared to the results of the Mothers Survey.

(g) Interpreting the prevalence data

The prevalence data captures respondents’ perceptions of the ways in which they were treated as a result of their pregnancy, parental leave and return to work following parental leave.

While only a court can determine whether there has been a breach of relevant legislation, the results indicate the prevalence of behaviour and action that could amount to discrimination due to an employee’s pregnancy, requests for or taking of parental leave, and return to work following parental leave (which potentially enlivens the SDA grounds of sex, pregnancy, family responsibilities and/or breastfeeding discrimination). The results should not be interpreted as findings as to whether unlawful discrimination had in fact occurred.

The prevalence data may be used as ‘baseline data’ for comparisons in the future.

Measuring the prevalence of discrimination

The prevalence of discrimination was measured at three points in time:

- in the workplace prior to the birth/adoption of the child

- when requesting or while on parental leave

- after the birth/adoption in relation to family responsibilities and breastfeeding/expressing.

Respondents were asked, for each of these points in time, if they had ever been ‘treated unfairly or disadvantaged’ (the plain-English definition of discrimination) because they were pregnant; because they took or requested to take leave to care for the child; because of their family responsibilities and breastfeeding/expressing in their first job after the birth of the child – and if so, what was the nature of that unfair treatment.

All respondents were also asked if they had experienced specific behaviour and actions that can constitute discrimination (see pages 44-46).

An overall incidence of the level of workforce discrimination relating to pregnancy was calculated as the total number of individuals who identified they were discriminated against according to the plain-English definition (‘treated unfairly or disadvantaged’) or reported that they experienced an action or behaviour that may constitute discrimination, on at least one occasion.

The survey was designed to capture the specific experiences of particular demographic groups. Some of the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents which was collected through the survey questionnaire included data in relation to:

- age

- gender[64]

- whether the respondent has a disability

- whether the respondent was a sole income earner during their pregnancy/adoption, when they requested or took parental leave or when they returned to work.

Other demographic data was available through the DSS database from which respondents were randomly surveyed including data in relation to:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status

- Culturally and linguistically diverse background.[65]

Given the small sample sizes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondents, culturally and linguistically diverse respondents and respondents with a disability, the findings for these groups should be regarded as indicative only and care should be taken in extrapolating those findings to the general population.

The values presented throughout the Report have been rounded to whole numbers points (with the exception of those values between 0% and 1%). Therefore the bars on the graphs presented throughout the Report may not appear to be equal though they are reported as having the same value. Please note that this is due to rounding and is not an error.[66]

This chapter provides an overview of the major findings, focusing on some of the major differences between diverse groups of survey respondents.

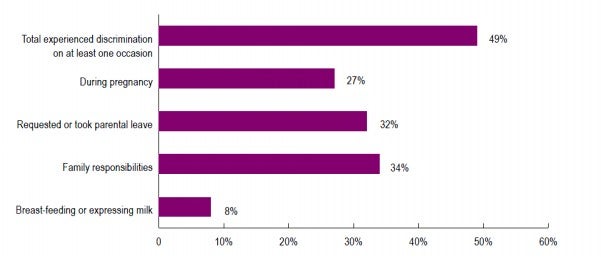

(a) Prevalence of discrimination

Discrimination in the workplace against mothers is pervasive.

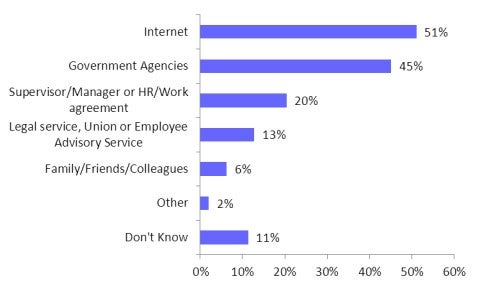

One in two (49%) mothers[67] reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace at some point during pregnancy, parental leave[68] or on return to work.[69]

Discrimination was reported at all stages:

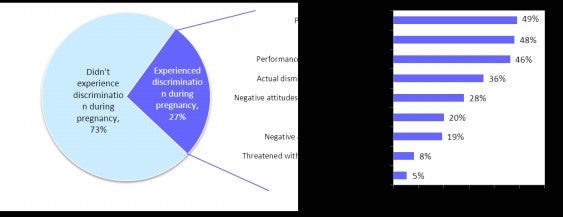

- A quarter (27%) of mothers reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace during pregnancy.

- Almost a third (32%) of mothers reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace when they requested or took parental leave.

- More than a third (35%) reported experiencing discrimination when returning to work after parental leave (34% related to family responsibilities and 8% related to breast-feeding or expressing milk).

Figure 1 - Prevalence of discrimination in the workplace during pregnancy, parental leave and return to work[70]

Base: Total respondents: (n=2002); During pregnancy: mothers (n= 2001); when requested or took parental leave: mothers who took leave or would have liked to take leave (n=1902); mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576)

Of the 49% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination, more than half (55%) reported experiencing discrimination at more than one point in time.[71]

(b) Type of discrimination[72]

* Please refer to the chart on pages 44-46 for a key to the ‘types of discrimination’ that are included in the categories below. Please note that respondents were allowed multiple responses.

Discrimination is experienced in many different forms ranging from negative attitudes in the workplace through to job loss.

Many mothers experience more than one form of discrimination during pregnancy, parental leave and return to work.[73]

One in five (18%) mothers indicated that they were made redundant/restructured/dismissed or that their contract was not renewed, either during their pregnancy, when they requested or took parental leave, or when they returned to work.

Types of discrimination experienced during pregnancy

Of the 27% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace during pregnancy:

- More than a third (36%) reported that they had been made redundant/restructured, were dismissed or did not have their contract renewed.

- Half (49%) reported discrimination related to pay, conditions and duties.

- Nearly half (48%) reported discrimination related to their health and safety.

- Nearly half (46%) reported discrimination related to their performance assessment or career advancement opportunities.

Figure 2 – Types of discrimination during pregnancy[74]

Of the 27% of mothers who experienced discrimination during pregnancy ...

Base: Mothers (n=2001): Experienced discrimination during pregnancy (n=482)

Types of discrimination experienced when requesting or on parental leave

Of the 32% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace when requesting or on parental leave:

- Over two thirds (69%) reported discrimination related to pay, conditions and duties.

- Almost half (46%) reported discrimination in relation to their performance assessment and career advancement opportunities.

- More than a quarter (29%) reported that they were made redundant/restructured, were dismissed or did not have their contract renewed when they requested or took leave.

Figure 3 – Types of discrimination when requesting or on parental leave[75]

Of the 32% of mothers who experienced discrimination when requesting or during parental leave ...

Base: Mothers who requested or took parental leave (n=1902): Experienced discrimination when requesting or on parental leave (n=615)

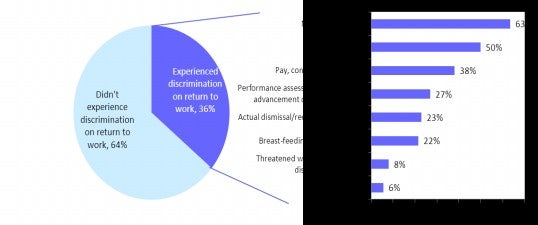

Types of discrimination experienced upon return to work

Of the 36% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace when returning to work after parental leave:

- Nearly two thirds (63%) reported receiving negative attitudes or comments from colleagues or managers/employers.[76]

- Half (50%) reported discrimination when they requested flexible work arrangements.

- Two in five (38%) reported discrimination related to pay, conditions and duties.

- Nearly a quarter (23%) reported being made redundant/restructured, were dismissed or did not have their contract renewed.

- One in five (22%) reported discrimination related to breastfeeding or expressing milk.

Figure 4 – Types of discrimination on return to work[77]

Of the 36% of mothers who experienced discrimination on return to work ...

Base: Mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576); Experienced discrimination in the workplace on return to work (n=578)

*This chart provides a key to the types of discrimination within each broad category of discrimination

|

Negative attitudes

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your employer/manager about your pregnancy (pregnancy)

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your colleagues about your pregnancy (pregnancy)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your employer/manager because you requested or took leave to care for your child (parental leave)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your colleagues because you requested or took leave to care for your child (parental leave)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments about breastfeeding or expressing milk (return to work)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments about working part-time or flexible hours (return to work)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments about needing time off to care for your child due to illness (return to work)

|

|

|

You were viewed as a less committed employee (return to work)

|

|

|

You were unfairly criticised about your performance at work (return to work)

|

|

|

Pay, conditions and duties

|

Your hours were changed against your wishes

|

|

Your roster schedule was changed against your wishes (pregnancy and parental leave)

|

|

|

Your duties or role were changed against your wishes

|

|

|

You were made casual (pregnancy and parental leave)

|

|

|

You had a reduction in your salary or bonus

|

|

|

You didn't receive a pay rise or bonus, or received a lesser pay rise or bonus than your peers at work

|

|

|

You missed out on a salary increment or bonus (parental leave)

|

|

|

Your position was replaced permanently by another employee (parental leave and return to work)

|

|

|

Your employer did not adequately backfill your position during your parental leave and this negatively impacted you (parental leave)

|

|

|

Performance assessments and career advancement opportunities

|

You were unfairly criticised about your performance at work (pregnancy)

|

|

You failed to gain a promotion you felt you deserved (pregnancy and return to work)

|

|

|

You were denied access to training that you would otherwise have received (pregnancy and return to work)

|

|

|

You missed out on opportunities for training (parental leave)

|

|

|

You missed out on opportunities for promotion (parental leave)

|

|

|

You missed out on a performance appraisal (parental leave)

|

|

|

Job loss/dismissal

|

You were treated so poorly that you felt you had to leave

|

|

You were threatened with redundancy or dismissal

|

|

|

You were made redundant/restructured

|

|

|

You were dismissed

|

|

|

Your contract was not renewed

|

|

|

Leave

|

You were unfit for work due to pregnancy-related illness or because your pregnancy ended and your employer denied you special unpaid maternity leave (pregnancy)

|

|

You were denied leave to attend medical appointments for your pregnancy (pregnancy)

|

|

|

Your employer encouraged you to start or finish your parental leave earlier or later than you would have liked (parental leave)

|

|

|

You were denied leave that you were entitled to (parental leave)

|

|

|

Health and safety

|

You were unable to take toilet breaks as you needed (pregnancy)

|

|

You were not provided with a suitable uniform (pregnancy)

|

|

|

Your work/workload was not adequately adjusted to accommodate your pregnancy (pregnancy)

|

|

|

Your health and safety were jeopardised by failure to accommodate your pregnancy (pregnancy)

|

|

|

You were not provided with a safe job (pregnancy)

|

|

|

You were transferred to a safe job but it involved a different number hours of work that you did not agree to (pregnancy)

|

|

|

You were transferred to a safe job but did not have the same terms and conditions of employment (pregnancy)

|

|

|

You were not provided with appropriate breastfeeding or expressing facilities (return to work)

|

|

|

Flexible work

|

Your requests for flexible hours or work from home were denied (return to work)

|

|

Your requests for time off to cope with illness or other problems with your baby were denied (return to work)

|

|

|

You were given unsuitable work or workloads (return to work)

|

|

|

You were given work at times that did not suit your family responsibilities (return to work)

|

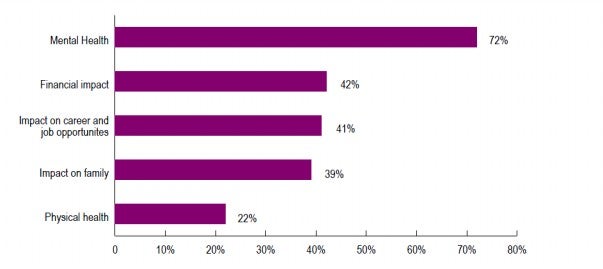

(c) Impact of discrimination

Discrimination has a significant negative impact on mothers’ health, finances, career and job opportunities and their family.

84% of mothers who experienced discrimination on at least one occasion reported a negative impact as a result of that discrimination.

- Two thirds (72%) reported that the discrimination impacted on their mental health. Mental health included stress and impact on their self-esteem and confidence.[78]

- Two in five (42%) reported that the discrimination had a financial impact on them, while a similar proportion (41%) felt that it impacted on their career and job opportunities.

Figure 5 – Impact of discrimination experienced[79]

Base: Total experienced discrimination on at least one occasion (n=978)

Discrimination has a negative impact on women’s engagement in the workforce and their attachment to their workplace.

- Of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination at work during their pregnancy, 22% did not return to the workforce as an employee. In contrast, only 14% of mothers who reported not experiencing discrimination at work during their pregnancy did not return to the workforce as an employee.

- Of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination at work during their pregnancy, 23% did not return to the ‘main employer’[80] they had before the birth/adoption of their child. In contrast, only 13% of mothers who reported not experiencing discrimination during their pregnancy did not return to their ‘main employer’.[81]

Mothers who reported that their employer was supportive during their pregnancy were less likely to report that they experienced discrimination. They were also more likely to return to work for that employer.

While 97% of mothers who did not experience discrimination during pregnancy said that their employer was supportive during their pregnancy[82], only 53% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination during pregnancy said their employer was supportive during their pregnancy.[83] Furthermore, while 98% of mothers who did not experience discrimination on return to work said their employer was supportive on return to work,[84] only 66% of mothers who reported experiencing discrimination on return to work said their employer was supportive on their return to work.[85]

Of the mothers who reported that their employer was supportive or very supportive of them during their pregnancy, almost nine in ten (87%) returned to the same employer after leave. This compares to just over half (53%) of mothers who reported returning to work for the same employer who was unsupportive or very unsupportive during their pregnancy.[86]

(d) Response to discrimination

Three in four (75%) mothers reported that they took action in response to discrimination they experienced on at least one occasion. These actions ranged from discussing it with friends, family or a colleague, through to making a formal complaint or resigning.[87]

Nearly a third of mothers who experience discrimination look for another job or resign.

32% of all mothers who were discriminated against at some point went to look for another job (13%) or resigned (19%).

Very few mothers who experience discrimination make a formal complaint.

91% of mothers who experienced discrimination did not make a formal complaint.

Only 6% of mothers who experienced discrimination made a formal complaint within their organisation, only 4% made a complaint to a government agency.

There was little difference between the actions taken in response to discrimination across the stages. However it is noteworthy that those who reported experiencing discrimination on return to work were less likely to make a complaint to a government agency than those who reported experiencing discrimination during pregnancy.

Figure 6- Actions taken in response to discrimination experienced[88]

Base: Mothers who experienced discrimination during pregnancy (n=482), when requested or on parental leave (n=615), on return to work (n=578)

Mothers do not take action in response to discrimination for a range of reasons.

A quarter (25%) of mothers who experienced discrimination did not take any action in response to that discrimination. The most common reasons mothers gave for not taking action included:

- they perceived that the discrimination was not serious enough, it didn’t bother them or that they sorted it out (27%)

- it was too hard, stressful or embarrassing for them to take action (24%)

- they felt that they would not be believed or nothing would change (22%).

In addition, one in ten (11%) mothers who did not take action said that they feared that taking action would impact on their job/career, while a similar proportion (9%) were not aware that they could take action, not aware how to take action or who to report it to, or were advised not to by family, friends or co-workers.

The majority of mothers taking some form of action in response to discrimination reported that it did not resolve the problem.

- Three in five (61%) mothers who took action in response to the discrimination they experienced while they were pregnant indicated that the issue was not resolved.

- Just over half (57%) of mothers who took action in response to discrimination when they requested or were on parental leave reported that the issue was not resolved.

- Just over half (55%) of mothers who took action in response to discrimination upon returning to work reported that the issue was not resolved.

(e) Characteristics of the individual, their employment and their workplace

The results were examined by characteristics of the individual, their employment and their workplace (eg type of employment contract, occupation, industry and size of organisation).

The results were not able to be weighted to reflect the population of working mothers by these characteristics because ABS data on the distribution of working mothers across these variables was not available. However, the distribution of survey respondents across these variables is comparable to ABS estimates of working women and therefore the prevalence of discrimination across these characteristics can be estimated.

(f) Experiences of discrimination by characteristics of the individual

The prevalence data was analysed according to a range of characteristics of the individual. The data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification, culturally and linguistically diverse background and disability is based on a small sample and should be treated as indicative.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification

24 mothers reported that they were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, with 13 out of these 24 mothers (58%) reporting they experienced discrimination on at least one occasion.

Culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds[89]

214 mothers identified as being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background. 109 out of the 214 mothers (51%) reported experiencing discrimination on at least one occasion.

Disability

41 mothers reported that they have a disability. 21 out of these 41 mothers (52%) reported experiencing discrimination on at least one occasion.

Age[90]

Young mothers (aged 18-24 years) are more likely to experience discrimination during pregnancy than mothers from older age groups.

During pregnancy, almost one in two (45%) mothers aged 18-24 years reported experiencing discrimination compared to one in four (24%) of all other mothers.

Sole income earner

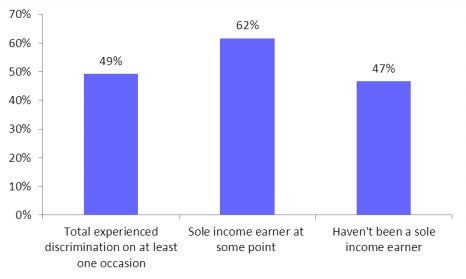

Mothers who are the sole income earner at some point during their pregnancy, parental leave or return to work are more likely to experience discrimination.

Among survey respondents, mothers who reported being a sole income earner at some stage during their pregnancy, parental leave or upon returning to work were more likely to experience discrimination (62%) when compared to mothers who were not sole income earners (47%).

Figure 7 – Experience of discrimination by sole income earner status[91]

Base: Total respondents (n=2002), sole income earner at some point (n=296), haven’t been sole income earner (n=1705), refused (n=1)

Experiences of sole income earning mothers[92]

Mothers who were sole income earners during pregnancy experienced different types of discrimination than mothers who were not sole income earners during pregnancy:

- pay, conditions and duties (26% vs 11% respectively)

- health and safety (24% vs 11% respectively)

- performance assessments and career advancement opportunities (23% vs 11% respectively)

- negative attitudes and comments from their employers/managers (16% vs 7% respectively).

Overall, mothers who were sole income earners at some point during their pregnancy, parental leave or on return to work, were more likely to say that the discrimination they experienced caused them stress (77%) compared to mothers who were not sole income earners (64%). Mothers who were sole income earners were also more likely to say that the discrimination impacted on them financially (54%), compared to mothers who were not sole income earners (39%).

Household arrangement

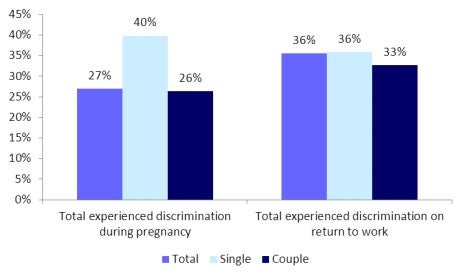

Single mothers are more likely to experience discrimination during pregnancy.

Among survey respondents, mothers who were single during their pregnancy were more likely to experience discrimination during pregnancy (40%) in comparison with mothers who were in a relationship during their pregnancy (26%).

Figure 8 – Experience of discrimination by household arrangement[93]

Base: Mothers (n=2001): Mothers who were single during pregnancy (n=94), mothers who were in a relationship during pregnancy (n=1903), refused (n=4); mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576): mothers who returned to work as an employee and was single on return to work (n=66), mothers who returned to work as an employee and was coupled on return to work (n=1508), refused (n=2)

Experiences of single mothers[94]

Mothers who were single during pregnancy or upon returning to work were more likely to say that the discrimination they experienced impacted upon them financially (57%) when compared with mothers who were in a relationship (29%).

(g) Experiences of discrimination by characteristics of employment

Discrimination reported by mothers during pregnancy, parental leave or on return to work was examined by whether mothers worked full-time or part-time, by whether they were employed on a permanent/ongoing, fixed-term contract or casual basis, by the length of their employment, and by their occupation.

The results revealed that part-time and full-time mothers experienced similar levels of discrimination.[95] However there were differences in the extent of discrimination by type of employment contract, length of employment and occupation.

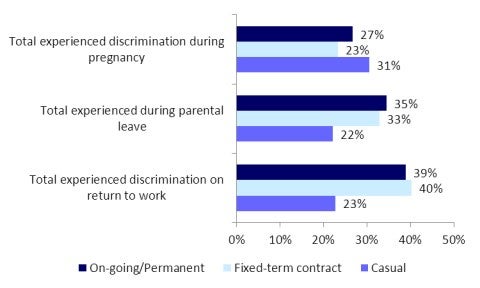

Type of employment contract

Among survey respondents, mothers who were in a casual position were more likely to report experiencing discrimination during pregnancy (31%) compared to 27% of mothers on permanent/ongoing contracts and 23% of mothers on fixed-term contracts.

However mothers on fixed-term or on-going/permanent contracts were more likely to experience discrimination upon requesting or taking parental leave and upon return to work:[96]

- Mothers who requested to take leave or took leave and worked in a permanent/on-going position (35%) or worked on a fixed-term contract (33%) were more likely to experience discrimination when they requested or took parental leave when compared to those who worked as a casual (22%).

- Mothers who returned to work after the birth/adoption of their child and who were on fixed-term contracts (40%) or permanent/on-going positions (39%) were more likely to experience discrimination on return to work when compared to those who were in a casual position (23%).

Experience of casual workers[97]

During pregnancy, mothers in the survey sample who were in a casual position were more likely to report being dismissed, being made redundant or losing their job (14%) compared with those in a permanent position (9%).[98]

Mothers who were employed on a casual basis and experienced discrimination upon return to work were more likely to resign in response to the discrimination they experienced (24%) compared with permanent employees (8%).

Figure 9 – Experience of discrimination by work status[99]

Base: Mothers in on-going permanent position during pregnancy (n= 1489), fixed-term contract (n=186), casual (n=321); mothers who took or would have liked to take leave in on-going permanent position during pregnancy (n=1457), fixed-term contract (n=177), casual (n=265); mothers who returned to work as an employee in on-going/permanent position (n=1130), fixed-term contract (n=152), casual (n=289).

Tenure

Mothers in the survey sample who worked for their employer for less than twelve months prior to the birth of their child, were more likely to report being discriminated against during their pregnancy (40%) when compared with mothers who reported working with their employer longer than twelve months.[100] Those who worked with their employer for more than ten years were least likely to report experiencing discrimination during their pregnancy (18%).

Experiences of mothers who worked for their employer for less than 12 months[101]

Mothers who had worked for their employer for less than twelve months prior to the birth of their child and experienced discrimination at some point were most likely to report the discrimination had an impact on them financially, on their family and their career and job opportunities.

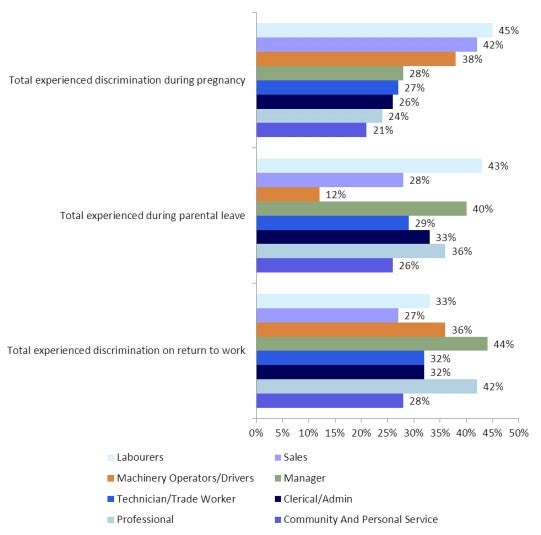

Occupation

Respondents were asked to report on their occupation.

The results revealed differences in the experience of discrimination depending on the occupation of survey respondents. It should be noted however that the figures for mothers who were employed as labourers and machinery operators/drivers should be taken as indicative only given the small sample size.

During pregnancy, 42% of mothers who were employed as ‘sales’ workers reported experiencing discrimination compared to 28% of mothers employed as ‘managers’ or smaller numbers in other occupations. When requesting or taking parental leave and upon return to work however, mothers employed as ‘managers’ or ‘professionals’ were more likely to experience discrimination. Among the survey sample:

- 40% of mothers who were employed as ‘managers’ reported experiencing discrimination when requesting or on parental leave and 44% reported experiencing discrimination on return to work

- 36% of mothers who were employed as ‘professionals’ reported experiencing discrimination when requesting or during parental leave and 42% on return to work.

Figure 10 – Experience of discrimination by occupations[102]

Base: Mothers (n=2001): during pregnancy: manager (n=230), professional (n=695), technician (n=75), community and personal service (n=389), clerical/admin (n=340), sales (n=206), machinery operators/drivers (n=18), labourers (n=44); total requested or took parental leave (n=1902): manager (n=222), professional (n=671), technician (n=72), community and personal service (n=373), clerical/admin (n=326), sales (n=181), machinery operators/drivers (n=18), labourers (n=35); total returned to work as an employee (n=1576): manager (n=179), professional (n=595), technician (n=56), community and personal service (n=309), clerical/admin (n=256), sales (n=136), machinery operators/drivers (n=12), labourers (n=28)

(h) Experiences of discrimination by nature of the workplace

Regardless of size, sector, industry or location of the workplace, discrimination can manifest in all types of workplaces. Discrimination was more likely to be reported by respondents in large workplaces, and in male dominated industries.[103]

Size of organisation

Respondents were asked to identify the size of the organisation they worked for and these were classified as small (less than 20), medium (20-99) and large (over 100).[104]

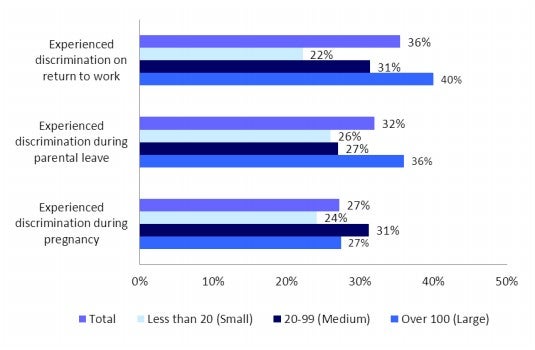

Among survey respondents, two in five (36%) mothers who worked in large organisations reported experiencing discrimination when they requested or took parental leave in comparison to one in four (26%) mothers who worked in small organisation and one in four (27%) mothers who worked in medium sized organisation.

Experiencing discrimination on return to work was more likely to be reported by those who returned to work in a large organisation (40%) than those who returned to work in small (22%) and medium (31%) organisations.[105]

Figure 11 – Experience of discrimination by size of the organisation[106]

Base: mothers (n=2001): small organisation size during pregnancy (n=321), medium (n=364), large (n=1265), don’t know (n=51); mothers who took leave or would have liked to take leave (n=1902): small organisation during parental leave (n=290), medium (n=345), large (n=1223), don’t know (n=44); mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576): small organisation on return to work (n=223), medium (n=270), large (n=1056), don’t know (n=27)

Industry

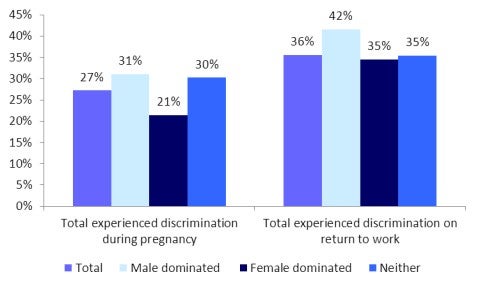

Respondents were asked to report on their industry type during pregnancy/prior to the birth of their child and upon return to work (if they had returned to work). The industries of survey respondents were then classified into male dominated, female dominated, or neither male nor female dominated industries (see Appendix B.4 for classifications).

Survey respondents who worked in male dominated industries during pregnancy were more likely to report experiencing discrimination (31%) than those who worked in female dominated industries (21%).

Figure 12 – Experience of discrimination during pregnancy and on return to work by male/female dominated industries[107]

Base: mothers (n=2001): worked in male dominated industries during pregnancy (n=261), female dominated (n=714), neither (n=1016), refused (n=10); Mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576): worked in male dominated industries on return to work (n=190), female dominated (n=598), neither (n=780), refused (n=8).

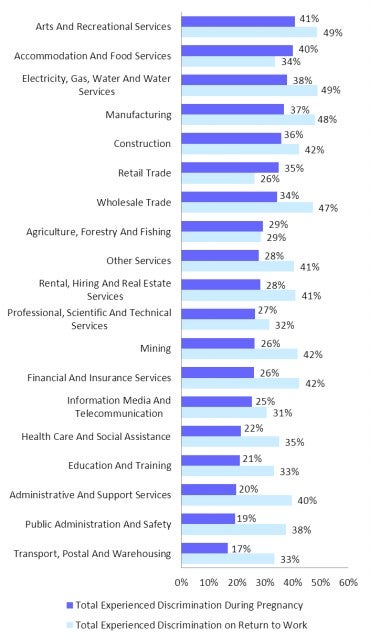

When the experience of discrimination was examined by each industry (Figure 13 below), it revealed that survey respondents who work in accommodation and food services and retail trade faced a different pattern of discrimination than mothers in other industries, with more mothers in accommodation and food services and retail trade facing discrimination during pregnancy than on return to work.

Figure 13 – Experience of discrimination during pregnancy and on return to work by industries[108]

Base: Mothers (n=2001); Arts And Recreational Services (n=45), Accommodation And Food Services (n=100), Electricity, Gas, Water And Water Services (n=26), Manufacturing (n=72), Construction (n=38), Retail Trade (n=202), Wholesale Trade (n=17), Agriculture, Forestry And Fishing (n=31), Rental, Hiring And Real Estate Services (n=23), Other Services (n=199), Professional, Scientific And Technical Services (n=92), Mining (n=33), Financial And Insurance Services (n=155), Information Media And Telecommunication (n=71), Health Care And Social Assistance (n=452), Education And Training (n=262), Administrative And Support Services (n=47), Public Administration And Safety (n=82), Transport, Postal And Warehousing (n=44).

Mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576); Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services (n=19), Arts and Recreation Services (n=32), Manufacturing (n=53), Wholesale Trade (n=12), Financial and Insurance Services (n=125), Construction (n=27), Mining (n=22), Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services (n=18), Other Services (n=146), Administrative and Support Services (n=37), Public Administration and Safety (n=68), Health Care and Social Assistance (n=392), Accommodation and Food Services (n=71), Transport, Postal and Warehousing (n=34), Education and Training (n=206), Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (n=78), Information Media and Telecommunications (n=53), Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (n=23), Retail Trade (n=152).

Workplace location[109]

Mothers who worked in a major city on return to work were more likely to experience discrimination (37%)[110] compared to mothers who worked in a large regional town (31%)[111] or a small regional town or rural area (26%)[112].

(i) Understanding of discrimination

Awareness of discrimination remains limited.

Respondents who said that they had not experienced unfair treatment as a result of their pregnancy, parental leave or family responsibilities were asked whether they had experienced specified actions and behaviours that are likely to constitute discrimination in the workplace related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth). See pages 44-46 for a list of actions and behaviours.

In addition to ensuring an accurate assessment of the incidence of discrimination in the workplace related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work,[113] this approach enables an individual’s understanding of discrimination to be measured.

The results reveal that a significant proportion of mothers are not aware that the actions and behaviours in relation to their pregnancy, taking leave and family responsibilities that they experienced, could constitute discrimination on the grounds of sex, pregnancy, breastfeeding or family responsibilities under the SDA.

Of those respondents who said they had not been treated unfairly because of their pregnancy, requesting or taking parental leave or because of their family responsibilities upon returning to work, one in three (36%) reported experiencing one or more actions or behaviours that could constitute discrimination related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work.

Figure 14 - Experience of discrimination in the workplace during pregnancy, parental leave and return to work by awareness[114]

Base: Total respondents: (n=2002); During pregnancy: mothers (n= 2001); when requested or took leave: mothers who took leave or would have liked to take leave (n=1902); mothers who returned to work as an employee (n=1576)

(j) Sources of information

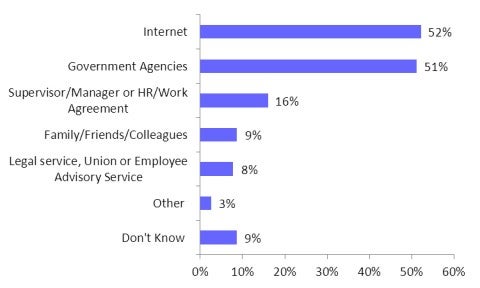

The internet and government agencies were the two most commonly reported sources of information on discrimination for mothers.

Half (51%) of mothers reported that they would use the internet to find information on their rights and entitlements relating to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work discrimination. A further 45% reported that they would get this information from government agencies.

The results also revealed that over one in ten (11%) mothers did not know where they would go to get information on their rights and entitlements about pregnancy, parental leave and return to work discrimination.

(k) Issues related to leave and return to work

The survey examined a range of issues related to the leave mothers took to care for their child and their return to the workplace. This section provides a snapshot of various issues related to the range of different types of leave mothers took to care for their child.[116]

(i) Length and type of leave

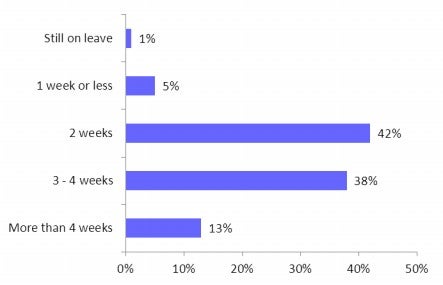

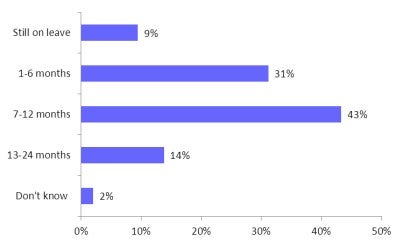

89% of mothers took leave to care for their child.

The length of leave mothers took was not a factor in the likelihood that they would experience discrimination.

Mothers took many different kinds of leave to care for their child.[117]

Three in five (60%) mothers took some form of leave other than (or in addition to) the 18 weeks leave required to be eligible for the Government’s PPL scheme. One in two (48%) took employer paid parental leave while similar proportions reported taking unpaid parental leave (46%) and annual leave (41%).

Young mothers, mothers who worked in small business and mothers who work part-time or casually were less likely to take leave.

- Mothers aged 18-24 years were less likely to take leave (74%) compared with mothers aged 25-34 years (93%) and those 35 years and older (92%).

- Two thirds (68%) of mothers who were employed on a casual basis during their pregnancy took leave to care for their child, while over nine in ten (95%) mothers in permanent positions took leave to care for their child.[118]

- Over nine in ten (94%) mothers who worked full-time during their pregnancy took leave to care for their child compared with over four in five (83%) mothers who worked part-time.

- The majority (93%) of mothers who worked in large workplaces during their pregnancy took leave to care for their child, while four in five (81%) mothers who worked in small workplaces, and nine in ten (90%) in medium workplaces took leave.

79% of mothers who took leave to care for their child returned to work within 12 months.

Figure 16 - Length of leave taken[119]

Of the 89% of mothers who took leave ...

Base: Mothers who took leave (n=1837)

The nature of mothers’ employment and workplace impacted on the length of leave they took to care for their child.

- Mothers who worked in the public sector during their pregnancy were more likely to take longer periods of leave.[120]

- Mothers employed on a permanent basis took longer periods of leave to care for their child than those employed on a casual basis.[121]

- Mothers who worked in larger workplaces were more likely to take longer periods of leave.[122]

Over two in five (45%) mothers surveyed reported that they would have liked to take leave[123] or additional leave to care for their child.

The shorter the length of leave taken, the more likely mothers were to say that they would have liked to take leave or additional leave.[124]

Seven in ten (70%) mothers who wanted to take leave or additional leave but did not take it, reported that it was because they could not afford to.

A small proportion of mothers reported that they had not returned to the workplace as an employee.

Nearly a quarter (23%) of mothers were still on leave or had not yet returned to work as an employee at the time of the survey.[125] Of this group:

- Half (49%) of mothers reported that they had not returned to work as an employee yet because they preferred to be at home, they preferred to continue breastfeeding, their partner earned enough or because they wanted to be self-employed.[126]

- One in six (17%) had another child or were pregnant again.

- One in seven (14%) could not find childcare or thought that childcare was too expensive.

- One in ten (11%) could not find work or could not negotiate return to work arrangements.

Three in four (75%) mothers did not plan to return to the same employer as before the birth or adoption of their child.[127] Of this group:

- A quarter (26%) of mothers did not intend to return because they either disliked their manager, the culture of the organisation or because their workplace did not allow flexible work arrangements.

- Nearly one in five (22%) mothers reported that the location of home/work was their reason for not returning to the same employer.

- One in six (16%) mothers reported that they did not want to return to the same employer because they were replaced, fired or made redundant or because their employer did not keep their job open.

(ii) Being kept informed of major changes or opportunities in the workplace

Mothers who experienced discrimination were less likely to be kept informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them.

Two in five (38%) mothers who took leave reported that their employer kept them informed of major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them. A similar proportion (35%) reported that their employer did not and just over a quarter (27%) said there were no major changes or opportunities in the workplace to be kept informed about.[128]

Among survey respondents, mothers who reported experiencing discrimination during pregnancy or parental leave were more likely to report that their employer did not keep them informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them:

- Over half (57%) of mothers who experienced discrimination during pregnancy reported that their employer did not keep them informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them, compared to just over a quarter (27%) of mothers who did not experience discrimination during pregnancy.

- Over half (55%) of mothers who experienced discrimination when requesting or during parental leave, reported that their employer did not keep them informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them, compared to nearly a quarter (24%) of mothers who did not experience discrimination when requesting or during parental leave.

(iii) Adjustments to working arrangements on return to work[129]

Most women request adjustments to their working arrangements and most requests are granted.

Of the 84% of mothers who returned to work as an employee, just over two-thirds (70%) requested adjustments to their working arrangements.[130]

The most common types of working arrangements requested were part-time work or jobsharing (50%), flexible hours (32%), a change in starting and finishing times (16%) and changing shift/roster (15%).

The results revealed that the majority of requests for adjustments to working arrangements were granted (89%)

2.3 Fathers and Partners Survey

This survey provides the survey results of the experiences of discrimination of fathers and partners who took the legislative entitlement to two weeks of pay (at the minimum wage) under the DaPP scheme for leave taken to care for their child.

1001 fathers and partners were interviewed as part of this survey. While the results of the survey are representative of the experiences of fathers and partners who take DaPP, they are not representative of the experiences of all fathers and partners in Australia. Thus, unlike the Mothers Survey, the results of the Fathers and Partners do not establish national prevalence rates of discrimination for fathers and partners.[131] The results do however provide an important insight into the experiences of fathers and partners who took some time off work to care for their child.

The vast majority of fathers and partners interviewed took short periods of leave. Of the fathers and partners surveyed, 85% took less than four weeks of leave.

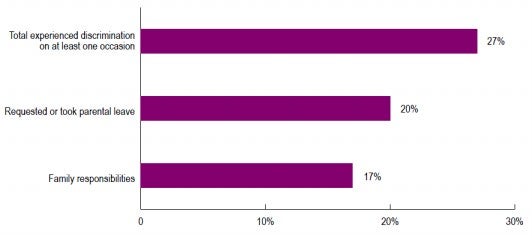

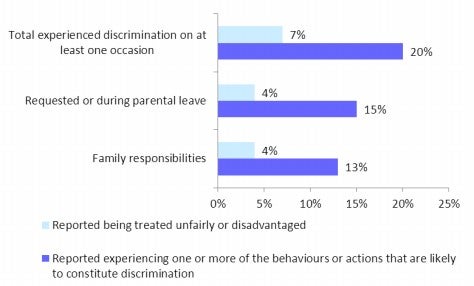

(a) Prevalence of discrimination

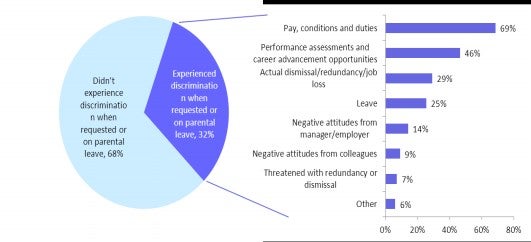

Despite taking very short periods of parental leave, fathers and partners face discrimination. Over a quarter (27%) of survey respondents reported experiencing discrimination when requesting or taking parental leave or when they returned to work.

Discrimination occurs at both stages:

- One in five (20%) fathers and partners reported experiencing discrimination when requesting or taking parental leave.

- One in six (17%) fathers and partners reported experiencing discrimination when they returned to work as an employee.

Figure 17 - Prevalence of discrimination in the workplace when requesting or during parental leave and return to work[132]

Base: During parental leave: all respondents (n=1001); family responsibilities: returned to work as an employee (n=977)

(b) Type of discrimination[133]

* Please refer to the chart on pages 44-46 for a key to the ‘types of discrimination’ that are included in the categories below. Please note that respondents were allowed multiple responses.

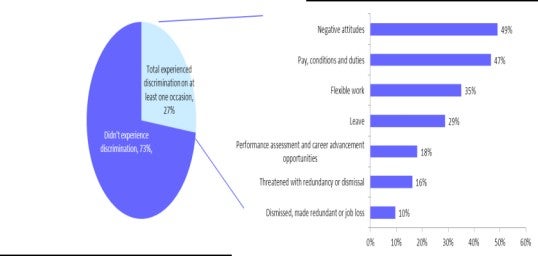

Fathers and partners experience discrimination in many different forms ranging from negative attitudes in the workplace through to dismissal.

Many fathers and partners experience more than one form of discrimination when requesting or during parental leave and on return to work.[134]

Of the fathers who experienced discrimination on at least one occasion (27%):

- Half (49%) reported receiving negative comments and attitudes from colleagues or manager/employer.[135]

- Nearly half (47%) reported discrimination related to pay, conditions and duties.

- A third (35%) experienced discrimination related to flexible work.

Figure 18 – Types of discrimination experienced[136]

Of the 27% of fathers and partners who experienced discrimination...

Base: All respondents (n=1001); experienced discrimination on at least one occasion (n=271)

*This chart provides a key to the types of discrimination that fall within each category.

|

Negative attitudes

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your employer/manager because you requested or took leave to care for your child (parental leave)

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments from your colleagues because you requested or took leave to care for your child (parental leave)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments about working part-time or flexible hours (return to work)

|

|

|

You received inappropriate or negative comments about needing time off to care for your child due to illness (return to work)

|

|

|

You were viewed as a less committed employee (return to work)

|

|

|

You were unfairly criticised about your performance at work (return to work)

|

|

|

Pay, conditions and duties

|

Your hours were changed against your wishes

|

|

Your roster schedule was changed against your wishes (parental leave)

|

|

|

Your duties or role were changed against your wishes

|

|

|

You were made casual (parental leave)

|

|

|

You had a reduction in your salary or bonus

|

|

|

You didn't receive a pay rise or bonus, or received a lesser pay rise or bonus than your peers at work

|

|

|

You missed out on a salary increment or bonus (parental leave)

|

|

|

Your position was replaced permanently by another employee

|

|

|

Your employer did not adequately backfill your position during your parental leave and this negatively impacted you (parental leave)

|

|

|

Performance assessments and career advancement opportunities

|

You were unfairly criticised about your performance at work (pregnancy)

|

|

You failed to gain a promotion you felt you deserved (return to work)

|

|

|

You were denied access to training that you would otherwise have received (return to work)

|

|

|

You missed out on opportunities for training (parental leave)

|

|

|

You missed out on opportunities for promotion (parental leave)

|

|

|

You missed out on a performance appraisal (parental leave)

|

|

|

Job loss/dismissal

|

You were treated so poorly that you felt you had to leave

|

|

You were threatened with redundancy or dismissal

|

|

|

You were made redundant/restructured

|

|

|

You were dismissed

|

|

|

Your contract was not renewed

|

|

|

Leave

|

|

|

Your employer encouraged you to start or finish your parental leave earlier or later than you would have liked (parental leave)

|

|

|

You were denied leave that you were entitled to (parental leave)

|

|

|

Flexible work

|

Your requests for flexible hours or work from home were denied (return to work)

|

|

Your requests for time off to cope with illness or other problems with your baby were denied (return to work)

|

|

|

You were given unsuitable work or workloads (return to work)

|

|

|

You were given work at times that did not suit your family responsibilities (return to work)

|

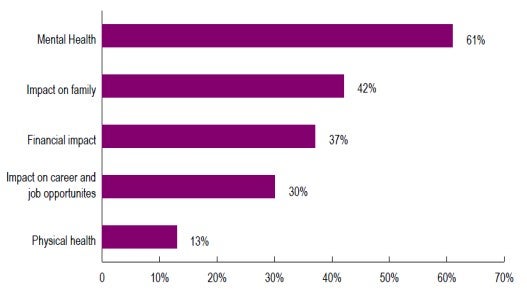

(c) Impact of discrimination

Discrimination has a significant negative impact on fathers and partners’ mental health, family, finances and career and job opportunities.

76% of fathers and partners who experienced discrimination during parental leave or on return to work reported a negative impact as a result.

- 61% of fathers and partners who experienced discrimination reported a negative impact on their mental health. This included on their level of stress and on their self-esteem and confidence.[137]

- Two in five (42%) reported that it had a negative impact on their families.

- Over a third (37%) said that this had a negative financial impact on them while a similar proportion (30%) felt it negatively impacted on their career and job opportunities.

Figure 19 – Impact of discrimination experienced[138]

Base: Total experienced discrimination on at least one occasion (n=271)

(d) Response to discrimination

A substantial proportion of fathers and partners who reported experiencing discrimination went to look for another job or resigned.

62% of fathers and partners who reported experiencing discrimination at some point took action in response to the discrimination.[139]

A quarter (23%) of fathers and partners who reported experiencing discrimination at some point went to look for another job and one in ten (10%) resigned.

95% of fathers and partners did not make a formal complaint[140] in response to the discrimination. Only 14 out of 271 (5%) of fathers and partners that experienced discrimination made a formal complaint within their organisation and only 4 out of 271 (2%) made a complaint to a government agency.

Figure 20 - Actions taken in response to discrimination experienced[141]

Base: Total experienced discrimination on at least one occasion (n=271)

Nearly half of fathers and partners who took action in response to the discrimination said that it did not resolve the problem.

Just under half (47%) of fathers who took action in response to the discrimination they experienced when they requested or took parental leave indicated that the issue was not resolved. Over two in five (45%) of those taking action in response to discrimination because of family responsibilities reported that the issue was not resolved.

(e) Characteristics of the individual, their employment and their workplace

The experience of discrimination was analysed by a range of demographic, employment and workplace characteristics.[142] Overall there were few differences between many of the sub-groups.

(i) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification, culturally and linguistically diverse background, and disability

The data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification, culturally and linguistically diverse background and disability is based on a small sample and should be treated as indicative.

11 fathers and partners identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. 5 out of the 11 (46%) reported experiencing discrimination on at least one occasion.

200 fathers and partners identified as being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background. 52 out of 200 (26%) reported experiencing discrimination on at least one occasion.

18 fathers and partners reported that they have a disability. 7 out of 18 (39%) experienced discrimination on at least one occasion.

(ii) Age

Young fathers and partners (aged 18-29 years[143]) were more likely to experience discrimination than fathers and partners from older age groups.

Nearly a third (31%) of fathers aged between 18 and 29 years experienced discrimination when they requested or took parental leave or when they returned to work, compared with 25% of fathers aged 30 years and over.

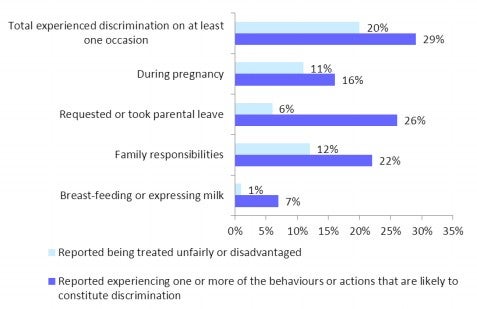

(f) Understanding of discrimination

Awareness of discrimination remains limited.

Respondents who said that they had not experienced unfair treatment as a result of requesting or taking parental leave or because of their family responsibilities, were asked whether they had experienced specified actions and behaviours that were likely to constitute discrimination in the workplace related to parental leave and return to work under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth). See pages 68-69 for a list of the actions and behaviours.

In addition to ensuring an accurate assessment of the incidence of discrimination in the workplace related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work, this approach enables an individual’s understanding of discrimination to be measured.

The results reveal that a significant proportion of fathers and partners are not aware that the actions and behaviours in relation to taking leave and family responsibilities that they experienced, can constitute discrimination on the grounds of family responsibilities under the SDA.

Of the fathers and partners who said that they were not treated unfairly or disadvantaged because they requested or took parental leave or because of their family responsibilities on return to work, one in five (21%) reported experiencing one or more action or behaviours that could constitute discrimination on the ground of family responsibilities.

Figure 21 - Prevalence of discrimination in the workplace during parental leave and return to work by awareness[144]

Base: During parental leave: all respondents (n=1001); family responsibilities: returned to work as an employee (n=977)

(g) Sources of information

The internet and government agencies were the two most commonly reported sources of information for fathers and partners.

Half (52%) of the fathers and partners surveyed reported that they would use the internet to find information on their rights and entitlements about discrimination related to parental leave or return to work. A further half (51%) said that they would seek information from government agencies.

The results also revealed that 9% of fathers and partners did not know where to go to get information.

(h) Issues related to leave and return to work

The survey examined a range of issues related to the leave fathers and partners took to care for their child and their return to the workplace. Fathers and partners took a range of different types of leave to care for their child. This section reports on all of these kinds of leave.

(i) Length and type of parental leave

Fathers and partners took a range of different types of leave.

Just over half (54%) of fathers and partners took some form of leave to care for their child other than leave they took to be eligible for the DaPP.[146] Three in five (61%) took annual leave, one in four (23%) took unpaid parental leave and one in five (19%) took employer paid parental leave.

85% of fathers and partners took less than 4 weeks of leave.

The nature of employment and workplace impacts on the length of leave taken.

- Fathers and partners who were employed on a casual basis were most likely to take just the two weeks of DaPP leave.[148]

- Fathers and partners who worked in small business were more likely to take two weeks or less of leave. [149]

Three in four (75%) fathers said they would have liked to take additional leave.

Over half (57%) of the fathers and partners who wanted to take additional leave to care for their child but did not take it, reported that it was because they could not afford to. Other reported reasons for not taking additional leave included: not knowing it was possible (15%), not having enough or having used up all their annual leave entitlements (11%), not thinking it would be granted (9%).

(i) Being kept informed of major changes or opportunities in the workplace

Fathers and partners who experienced discrimination were less likely to be kept informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them.

Of the survey respondents, one in four (26%) fathers reported that their employer kept them informed of major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could have affected them while they were on leave, one in six (16%) reported that their employer did not, while three in five (58%) said there were no major changes or opportunities in the workplace to be kept informed about.

Fathers and partners who experienced discrimination when requesting or taking parental leave were more likely to report that their employer did not keep them informed about major changes or opportunities in the workplace that could affect them (28%) compared with fathers and partners who did not report experiencing discrimination (13%).

(j) Adjustments to working arrangements

One in five fathers and partners requested adjustments to their working arrangements on return to work.[150]

Of those fathers and partners who returned to work as an employee (99%), one in five (22%) requested adjustments to their working arrangements.[151]

The most common types of adjustments to working arrangements requested were flexible hours (34%), a change in starting and finishing times (24%), part-time work or jobsharing (14%) and a change in shift/roster (14%).

The results revealed that four in five (80%) requests for adjustments to working arrangements were granted. However, fathers who experienced discrimination on at least one occasion were less likely (59%) than those who did not experience discrimination to have their requests granted.[152]

2.4 Further research

The National Review received submissions identifying the need for additional research on specific aspects of pregnancy/return to work discrimination, including:

- On-going data collection on the prevalence, nature and consequences of pregnancy/return to work discrimination.

- Impacts and costs of discrimination to individuals, employers and the national economy.

- The potential connections between pregnancy and redundancy.

- Effective mechanisms for reducing the level of vulnerability of pregnant women, employees on parental leave and working parents to redundancy and job loss.

- Long term economic and social benefits to employers, employees, the wider community of increased workforce participation of parents.

- The incidence and nature of modifications made in workplaces following resolution of a discrimination complaint or a finding of pregnancy/return to work discrimination.

The National Review recommends the Australian Government:

- allocate funding to conduct a regular national prevalence survey on discrimination related to pregnancy, parental leave and return to work after parental leave (every four years)

- conduct further research into identified gaps, such as the most effective mechanisms for reducing the vulnerability of pregnant women, employees on parental leave and working parents to redundancy and job loss.

[53] Given the small number of survey respondents that reported they were an ‘adoptive’ mother (n=1), it is not possible to identify the specific experiences of adoptive mothers.

[54] The Commission acknowledges the contribution of the following academics in providing expert comment on the survey questionnaire and methodology: Marian Baird, University of Sydney; Sara Charlesworth, University of South Australia; Lyn Craig, University of New South Wales; Alexandra Heron, University of Sydney; Belinda Hewitt, University of Queensland, Paula McDonald, Queensland University of Technology; Lyndall Strazdins, Australian National University; and Gillian Whitehouse, University of Queensland.

[55] L Adams, F McAndrew and M Winterbotham, Pregnancy discrimination at work: a survey of women Equal Opportunity Commission (2005). At http://www.maternityaction.org.uk/wp/2013/11/pregnancy-discrimination-at-work-a-survey-of-women/ (viewed 1 April 2014).

[56] H Russell, D Watson and J Banks Pregnancy at Work: A National Survey, HSE Crisis Pregnancy Programme and Equality Authority (2011). At http://www.equality.ie/en/Research/Research-Publications/Pregnancy-at-Work-A-National-Survey.html (viewed 1 April 2014).

[57] For example, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4913.0 - Pregnancy and Employment Transitions, Australia, Nov 2011. At http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4913.0Main%20Features3Nov%202011?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4913.0&issue=Nov%202011&num=&view= (viewed 1 April 2014).

[58] See ‘Methodology’ for an overview of the role of the Reference Group and its membership.

[59] In the period in which the sample was drawn (May – November 2011), 98.5 of mothers were paid either the PPL or BB as a proportion of all children born in 2011–12 based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics publication 3222.0 Series B estimates. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), Annual Report 2011-2012, p 50. At http://www.dss.gov.au/about-fahcsia/publications-articles/corporate-publications/annual-reports/2012 (viewed 3 April 2014).

[60] All respondents to the survey worked for at least some of the time through their pregnancy. The sample structure for the PPL and BB survey was calculated using the November 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics’ ‘Pregnancy and Employment Transitions’. Survey Results which estimated that amongst mothers with a child born on or after 1 January 2011, who were in the workforce as an employee, 79% reported claiming PPL and 21% reported claiming BB. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4913.0 - Pregnancy and Employment Transitions, Australia, Nov 2011. At http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4913.0Main%20Features3Nov%202011?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4913.0&issue=Nov%202011&num=&view= (viewed 1 April 2014).

[61]The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) calculated that at the time of the survey 109,078 Australian women who were aged between 18 and 49 years, and were employed in the previous nine months as an employee, had given birth to a child in the six months prior to the time of the survey. This estimate was provided by ABS to the Commission for the purposes of weighting the survey data and was based on a Labour Force Survey estimate that 3.7 million women in this age group were employed as employees and that based on national age-specific fertility rates for women of this age, 109 078 of them would have given a birth to a child in a six month period. The unweighted number of respondents (N) has been reported in graphs and tables of data to indicate how many respondents answered the respective questions.

[62] See ‘Methodology’ for an overview of the role of the Reference Group and its membership.

[63] In the 6 month period following the introduction of the ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ scheme (January – June 2013), 26 212 fathers and partners accessed the scheme. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), Annual Report 2012-2013, p 40. At http://www.dss.gov.au/about-the-department/publications-articles/corporate-publications/annual-reports/fahcsia-annual-report-2012-2013 (viewed 1 April 2014).

[64] Two (n=2) respondents of the Mothers Survey identified as ‘X (indeterminate, intersex, unspecified)’.

[65] The data on whether the respondent was from a culturally and linguistically diverse background was incomplete for the Baby Bonus sample. It was therefore available for approximately 80% of the respondents to the Mothers Survey and all the respondents to the Fathers and Partners Survey.

[66] For example, two bars on the same graph may be labelled as 5% but may appear to be different visually. In this instance one may represent an actual value of 4.5% while the other may represent an actual value of 5.4% (both have been rounded to 5%).

[67] ‘Mothers’ refers to women aged 18-49 years and in the workforce as an employee at some time during their pregnancy (or while adopting a child) with a child of approximately two years of age.

[68] This Chapter refers to ‘parental leave’ (for example, discrimination experienced when requesting or taking parental leave), however it should be noted that mothers reported taking many different forms of leave to care for their child.

[69] An overall incidence of the level of workforce discrimination was calculated as the total number of individuals who were treated unfairly or disadvantaged at least once either during their pregnancy, when requesting or on parental leave, or when returning to work following parental leave.

[70] Survey questions: Q8, Q10/a/b, Q20,Q22/a/b, Q47, Q49, Q50/a/b

[71] That is, they reported discrimination at more than one of the following stages: during pregnancy; when requesting or on parental leave; or when returning to work following parental leave.

[72] Please see Appendix B.3 for the percentage of all mothers that experienced the different types of discrimination.

[73] The survey questions relating to type of discrimination allowed survey respondents to identify multiple types of discrimination they experienced. One in five (18%) mothers experienced more than one type of discrimination during pregnancy; One in five (21%) mothers who took leave or requested to take leave experienced more than one type of discrimination; A quarter (24%) of mothers who returned to work as an employee experienced more than one type of discrimination.

[74] Survey questions: Q8, Q9, Q10/a/b.

[75] Survey questions: Q20, Q21, Q22/a/b.

[76] It was not possible to separate out ‘negative attitudes’ received from ‘managers/employers’ and negative attitudes received from ‘colleagues’ for the return to work stage as the response codes on the survey questionnaire combined managers/employer and colleagues.

[77] Survey questions: Q47, Q48, Q49, Q50/a/b.

[78] 67% of mothers reported an impact on their level of stress, 44% reported an impact on their self-esteem and confidence, and 33% reported an impact on their mental health more generally.

[79] The survey questions relating to impact of discrimination allowed survey respondents to identify multiple impacts of the discrimination they experienced. Survey question; Q11, Q23, Q51

[80] Main employer’ refers to the job they had just prior to parental leave. If they had more than one job at the time it refers to the job for which they did the most number of hours per week.

[81] Mothers who have finished their parental leave and experienced discrimination at work during their pregnancy were less likely to return to the main employer they had before the birth/adoption of their child (77%), compared to mothers who didn’t experience discrimination during their pregnancy (87%).

[82] The remaining respondents said that their employer was neither supportive nor unsupportive.

[83] Of the remaining respondents (who had experienced discrimination during pregnancy), 21% said their employer was neither supportive nor unsupportive and 26% said their employer was unsupportive.

[84] The remaining respondents said that their employer was neither supportive nor unsupportive.

[85] Of the remaining respondents (who had experienced discrimination upon return to work), 17% reported that their employers was neither supportive nor unsupportive and 17% reported their employer was unsupportive.