Native Title Report 2009: Chapter 3

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Native Title Report 2009

Chapter 3: Towards a just and equitable native title

system

- 3.1 Improving the native title system – the time for change is now!

- 3.2 Recognition of traditional ownership

- 3.3 Shifting the burden of proof

- 3.4 More flexible approaches to connection evidence

- 3.5 Improving access to land tenure information

- 3.6 Streamlining the participation of non-government respondents

- 3.7 Promoting broader and more flexible native title settlement packages

- 3.8 Initiatives to increase the quality and quantity of anthropologists and other experts working in the native title system

- 3.9 Conclusion

3.1 Improving the native title system – the time

for change is now!

As I discussed in Chapter 1 of this Report, there was a new energy and a stir

of activity in the native title sector during the reporting period.

In my previous two Native Title Reports, I have strongly argued the

need to reform the native title system. Stakeholders from all sectors engaged in

the native title system have also stressed the need for the Government to take

significant steps to ensure that the system meets the original objectives set

out in the preamble to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Native Title

Act).

The federal Attorney-General has responded to this call and has committed to

improving the operation of the native title system. He has clearly identified

reform to the native title system as a strategic

priority.[1]

The Attorney-General has advanced reforms to the native title system aimed at

fostering ‘broader, quicker and more flexible negotiated outcomes for

native title claims’.[2] In

particular, the Native Title Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) commenced on 18

September 2009. I have outlined these reforms in Chapter 1 of this Report. The

Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs has

also worked with the Attorney-General and native title stakeholders to bring

about positive change in the system, with a particular focus on maximising the

benefits derived from native title

agreements.[3]

However, further reform is required to realise the hopes of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples for the system.

There are signs that the

Attorney-General recognises this.

The Government has indicated that it is receptive to constructive and

concrete ideas for reform. For example, the Attorney-General has stated:

I have an open mind as to how the operation of the system can be improved and

am willing to explore ideas for reform such as the amendments you proposed in

your 2008 Report.The Government is committed to genuine consultation with Indigenous people

and other relevant native title stakeholders in exploring ways to improve the

native title system. The Government will not rush into making significant change

to the Native Title Act. History has shown that such change requires

proper consideration and

consultation.[4]

I am greatly

encouraged by the Attorney’s comments.

Over the past 16 years, millions of dollars have been spent on the native

title system. There have been minimal obvious returns for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples. Significant studies have generated proposals for

improving the operation of the native title system. Yet, many reports are now

gathering dust on shelves in Canberra.

I consider that reforms are urgently required to improve the system and

fulfil the underlying purposes of the Native Title Act – including the

rectification of ‘the consequences of past

injustices’.[5]

The native title system must be viewed holistically. Its deficiencies can

only be addressed through a comprehensive reform process in which Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples are actively involved, every step of the way. I

reiterate my firm belief that any reform to the native title system needs to

respect the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and international human

rights standards. Reforms must not be implemented without full consultation and

the free, prior and informed consent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples.

We now have a historic opportunity to transform the native title system to

ensure that it truly delivers justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples and facilitates our social and economic development. The Attorney must

seize this opportunity and succeed where other governments have failed. To do so

would leave a lasting legacy of reconciliation.

It is therefore an optimal time to have an informed discussion about what

changes should be made to improve native title.

In Chapter 2 of this Report, I considered principles and standards that

should underpin a fresh approach to native title.

In Chapter 3, I raise a

number of my concerns about the native title system as it currently operates.

The purpose of this Chapter is to highlight possible options for reform and to

encourage further dialogue on ways to improve the native title system.

In particular, this Chapter considers several key areas that require

attention:

- recognition of traditional ownership

- shifting the burden of proof

- more flexible approaches to connection evidence

- improving access to land tenure information

- streamlining the participation of non-government respondents

- promoting broader and more flexible native title settlement packages

- initiatives to increase the quality and quantity of anthropologists and

other experts working in the native title system.

These issues have

been specifically identified throughout the reporting period as future

directions for reform.[6]

There are undoubtedly other elements of the native title system in need of

improvement, many of which I have analysed in previous Native Title

Reports. However, the range of issues raised in this Chapter indicates that

governments must do more than simply tinker at the edges of the native title

system to achieve social justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples.

3.2 Recognition of traditional ownership

The recognition of native title can be empowering for traditional owners.

The experience of Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation is that for claimant

groups

native title is not merely about gaining (generally quite limited) rights

over their traditional country. What is particularly important to many claimants

is the recognition and status that comes with a positive determination –

that is, that the white legal system and the Australian Government recognise the

existence of the group and their status as traditional

owners.[7]

Murray Wilcox, a former Federal Court judge, has also commented on the

significance of formal recognition for native title claimants:

A court decision to recognise native title always unleashes a tide of joy. I

believe this has nothing to do with any additional uses of the land –

generally very marginal – that the determination makes available; rather,

the fact that a government institution has formally recognised the claimant

group’s prior ownership of the subject land and the fact of its

dispossession. That recognition is what Aboriginal peoples are

seeking.[8]

As discussed in Chapter 2, the Australian Constitution does not recognise our

traditional ownership of our lands, territories and resources. Further, the

legal barriers for proving native title are often insurmountable, leaving many

communities without formal recognition of their traditional ownership.

In an attempt to overcome this significant issue, Mr Wilcox has raised the

idea of allowing courts to recognise traditional ownership when the claimants

fall short of proving native title.

He has suggested that the Federal Court should be empowered to make a

declaration about traditional ownership based on descent, and without needing to

find continuous observance of laws and customs, or to make orders about

particular uses of the land.[9]

This proposal is worthy of further consideration. It raises some important

questions. How might it work in practice? What rights would be associated with

recognition of traditional ownership, if not native title rights and interests?

Creating a ‘second tier’ of recognition of traditional owner

status could be useful in some circumstances. As the National Native Title

Council (NNTC) identifies:

Such a power would enable the regional identification of the traditional

country of a claimant group even where native title has been, for example,

extinguished by the grant of an extinguishing

tenure.[10]

However, in creating such a second tier, the Government should be very

careful not to simply give incentives for respondent parties to ‘race to

the bottom’ of the recognition ladder. As the NNTC further comments:

[T]he capacity for the Federal Court to make a determination of

‘traditional owner status’ [must] not operate to the disadvantage of

native title claimants. For example, it should not operate as an incentive to

respondents to reduce their willingness to participate in consent

determinations.[11]

While the idea of alternative modes of recognition is innovative, I consider

that the ultimate issue is: how do we transition from the existing law to a

native title system that works, and thereby allows full recognition of

traditional ownership? After all, the Native Title Act was intended to do

exactly that – give legal recognition to the traditional owners of this

land.

The devastating reality is that native title is inaccessible and unrealistic

for many traditional owners. This includes the Yorta Yorta people in Victoria,

who could not clear the legal hurdles of proving native title. In my view, the

answer is not necessarily to create a second tier of legal recognition of

traditional ownership, but to amend the law and make native title accessible and

achievable.

However, if such amendments are not made and native title determinations

remain elusive to the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,

the Government should consider and consult on how other mechanisms can

acknowledge traditional ownership. Some mechanisms such as consent

determinations and Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) already exist, but

their use as tools for recognition could be promoted and made more attractive

and accessible to the parties.

3.3 Shifting the burden of proof

(a) Background

Over the past five years, I have consistently voiced my concerns that the

evidential burden of proving native title is simply too great. Similarly, Les

Malezer has argued that the onus upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples of proving that they have a customary connection to their lands is one

of the ‘fundamentally discriminatory aspects’ of the Native Title

Act.[12]

This view is shared by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of

Racial Discrimination, which has expressed concern:

about information according to which proof of continuous observance and

acknowledgement of the laws and customs of indigenous peoples since the British

acquisition of sovereignty over Australia is required to establish elements in

the statutory definition of native title under the Native Title Act. The high

standard of proof required is reported to have the consequence that many

indigenous peoples are unable to obtain recognition of their relationship with

their traditional lands. ...[The Committee] recommends that the State party review the requirement of

such a high standard of proof, bearing in mind the nature of the relationship of

indigenous peoples to their

land.[13]

As one academic put it, ‘the question should not be how we can deal

with indigenous “claims” against the state, but rather how can the

colonisers legitimately settle and establish their own

sovereignty’.[14]

One way to address this problem could be to amend the Native Title Act to

provide certain presumptions in favour of native title claimants. For instance,

there could be a presumption of the ‘continuity of the relevant society

and the acknowledgement of its traditional laws and observance of its customs

from sovereignty to the present

time’.[15] Once these

presumptions are triggered, the burden would shift to the respondents to rebut

the presumptions with proof to the contrary.

Such an approach is not inconsistent with the Native Title Act. The preamble

states that the High Court has held that the common law ‘recognises a form

of native title that reflects the entitlement of the indigenous inhabitants of

Australia, in accordance with their laws and customs, to their traditional

lands’. Presumptions in favour of the native title claimants would simply

recognise and give respect to this fact.

Nor would this approach be novel. As I outlined in my submission to the

Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the

Native Title Amendment Bill 2009, there are a number of laws in Australia in

which a presumption is made or certain elements must be proven, after which the

burden of proof shifts to the

respondent.[16]

In most cases the government party would presumably take on the role of

adducing evidence to rebut the relevant presumptions. In my view, this is

appropriate. Government parties typically hold a lot of information relevant to

the claim. Governments are also better resourced than native title claimants.

Significantly, governments are responsible for dispossession.

As Tony McAvoy comments:

The evidence which traditional owners inevitably have to rely upon for that

period which is beyond the living memory of traditional owners comes from the

government. That material is often in the hands of the government or government

functionaries ... The state has the resources and the capacity to look at the

material itself. If it wants to challenge the continuity of particular

people’s connection then let them do so. Let them access their own

material and do so. Instead, the onus is placed upon the traditional owners and

complaints are made about the length of time it takes for claims to be

settled.[17]

Shifting the burden of proof is intended to encourage positive outcomes in a

higher proportion of native title claims, either by consent or through

litigation. If the burden of disproving a claim rests more heavily on the

respondents, states and territories may be more inclined to settle claims with

strong prospects of success by consent. It could mean, as Justice North and Tim

Goodwin argue, that for ‘most cases moving towards resolution by consent

determination, the timeline would be streamlined beyond recognition and the

costs of such a process would be reduced out of

sight’.[18]

However, this reform alone may not lead to better outcomes for native title

claimants. A respondent would still be able to defeat a native title claim due

to the operation of s 223, as currently interpreted and applied. And unless

the attitudes and behaviours of states and territories change, the system will

likely remain highly adversarial in nature.

In this section, I consider:

- what could trigger the presumptions in favour of native title claimants

- the benefits of a presumption of continuity

- proposals for reforms to terminology associated with the application of

s 223 of the Native Title Act, including ‘traditional’,

‘connection’ and ‘substantial interruption’ - the need for fundamental changes in the attitudes and behaviours of states

and territories to make these reforms work.

(b) Triggering presumptions in favour of native title

claimants

One option for further consideration is to amend the Native Title Act to

shift the burden of proof once native title claimants meet the registration

test. Section 190A of the Native Title Act requires the Native Title

Registrar to assess the merits of a native title claim, requiring the native

title applicants to submit evidence to:

- identify the area subject to native title

- identify the native title claim groups

- identify the native title rights and interests under claim

- provide a factual basis to the claim

- establish a prima facie case that at least some of the native title rights

and interests claimed in the application can be

established.[19]

Using

the registration test to trigger a shift in the burden of proof could allay

fears that such a change would result in opening the ‘floodgates’.

The Native Title Act also includes a number of other procedural requirements

related to the registration test that could act as a safeguard to address

floodgate concerns.[20]

If this proposal is adopted, it is important that the bar for meeting the

registration test is not raised. This would simply shift the current problems of

proof to an earlier stage in the claims process. It would also jeopardise access

to the important procedural rights that are gained through registration and

place the assessment of evidence outside the court system.

Alternatively, the presumption could be engaged (and the burden shift) once

the native title claimants prove certain threshold matters.

Chief Justice French of the High Court of Australia has suggested that the

Native Title Act could be amended to provide for a presumption in favour of

native title applicants, which ‘could be applied to presume continuity of

the relevant society and the acknowledgement of its traditional laws and

observance of its customs from sovereignty to the present

time’.[21] A presumption could

apply:

to an application for a native title

determination brought under section 61 of the Act where the following

circumstances exist:(a) the native title claim group defined in the application applies for a

determination of native title rights and interests where the rights and

interests are found to be possessed under laws acknowledged and customs observed

by the native title claim group(b) members of the native title claim group reasonably believe the laws and

customs so acknowledged to be traditional(c) the members of the native title claim group, by their laws and customs

have a connection with the land or waters the subject of the application(d) the members of the native title claim group reasonably believe that

persons from whom one or more of them was descended, acknowledged and observed

traditional laws and customs at sovereignty by which those persons had a

connection with the land or waters the subject of the

application.[22]

The Chief Justice further suggests that, once the above circumstances exist,

the following could be presumed in the absence of proof to the contrary:

(a) that the laws acknowledged and customs observed by the native title claim

group are traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed at

sovereignty(b) that the native title claim group has a connection with the land or

waters by those traditional laws and customs(c) if the native title rights and interests asserted are capable of

recognition by the common law then the facts necessary for the recognition of

those rights and interests by the common law are

established.[23]

Justice North and Tim Goodwin have also suggested legislative amendment to

establish a reverse onus of proof in native title applications. As to the

circumstances that would engage such a reverse onus, they comment:

Applicants would need to show that there were Indigenous people at

sovereignty occupying the land in question according to traditional laws and

customs. The onus would then shift to the respondents to demonstrate that the

other requirements of the Yorta Yorta test do not

exist.[24]

The circumstances that would trigger a presumption are worthy of further

consideration. Yet, a common theme from these proposals is that once the

presumptions are triggered, it should fall to the respondents to adduce evidence

to rebut the presumptions and prove the contrary.

(c) A presumption of continuity

At the very least, the Native Title Act should provide for a presumption of

continuity.

To prove native title, claimants are required to demonstrate continuity:

- of a society from sovereignty to the present

- in the observance of law and custom

- in the content of that law and

custom.[25]

However, as

Justice North and Tim Goodwin have observed,

those who have been most dispossessed by white settlement have the least

chance of establishing native title. They find it hardest, and usually

impossible, to establish that they belong to a society which has led a

continuous vital existence since white settlement because the policy of the

settlers had the effect of destroying or dissipating members of the society.

Consequently Indigenous people who were connected to areas the subject of

greater white settlement are further dispossessed of their lands by the

operation of native title

law.[26]

The application of the tests for continuity, derived from Yorta Yorta v

Victoria (Yorta Yorta) [27] has had a devastating effect on

native title claims. For example, the Larrakia people were unable to prove their

native title claim over Darwin because the Federal Court found their connection

to their land and their acknowledgement and observance of their traditional laws

and customs had been interrupted – even though they were, at the time of

the claim, a ‘strong, vibrant and dynamic

society’.[28]

Chief Justice French is of the view that a presumption:

could be applied to presume continuity of the relevant society and the

acknowledgement of its traditional laws and observance of its customs from

sovereignty to the present time. ... And if by those laws and customs the

people have a connection with the land or waters today, in the sense explained

earlier, then a continuity of that connection, since sovereignty, might also be

presumed.[29]

The Native Title Act should specify that, where a claimant meets the

threshold for triggering a presumption, continuity in the acknowledgement and

observance of traditional law and custom and of the relevant society shall be

presumed, subject to proof of substantial interruption. This would clarify that

the onus rests upon the respondent, usually the government party, to prove a

substantial interruption rather than upon the claimants to prove continuity.

This would mean that, if the respondent chose not to challenge the

presumption, the parties could, in practice, disregard a substantial

interruption in continuity of observance of traditional laws and

customs.[30]

However, these reforms alone would not lead to a just and fair native title

system. They need to be accompanied by amendments to s 223 of the Native

Title Act and, most importantly, shifts in the attitudes and behaviours of

states and territories.

(d) Reforms to section 223 of the Native Title

Act

Section 223 of the Native Title Act defines ‘native title’

and the rights and interests which constitute it. These include hunting,

gathering, fishing and other statutory rights and

interests.[31]

Section 223 has been interpreted and applied in successive court

decision in ways that deny the promise of recognition inherent in the preamble

to the Native Title Act. Consequently, reforms to s 223 are required to

ensure that the proposed presumptions operate fairly and justly.

This includes clarifying the definitions of ‘traditional’ and

‘connection’ as used in s 223(1) and the related concept of

‘substantial interruption’.

(i) Clarify

the definition of ‘traditional’

Native title rights and interests must be ‘possessed under the

traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed’ by

the claimants.[32]

Courts have interpreted ‘traditional’ to mean that laws and

customs must remain largely

unchanged.[33] If this

interpretation of ‘traditional’ is retained, it may be too easy for

a respondent to rebut the presumption of continuity by establishing that a law

or custom is not practiced as it was at the date of sovereignty.

I recommend that ‘traditional’ should encompass laws, customs and

practices that remain identifiable through time. This would go some way to

allowing for recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to culture and

would also clarify the level of adaptation allowable under the

law.[34]

(ii) Clarify the definition of

‘connection’

Section 223 requires that claimants ‘have a connection with the

land or waters’ that is the subject of the claim, and have such a

connection by virtue of their traditional law and customs.

The Native Title Act should explicitly state that claimants are not required

to have a physical connection with the land or waters.

Requiring evidence of physical connection sets an unnecessarily high standard

that may prevent claimants who can demonstrate a continuing spiritual connection

to the land from having their native title rights protected and recognised.

Since the Full Federal Court decision in De

Rose,[35] the courts have

rejected the need for the claimants to demonstrate an ongoing physical

connection with the land. However, setting this out clearly in s 223 would

assist to clarify this issue for courts and parties.

(iii) Clarify what constitutes ‘substantial

interruption’

In the Native Title Report 2008, I proposed amendments to the Native

Title Act to address the court’s inability to consider the reasons for an

interruption to the observance of traditional laws and

customs.[36]

Currently, the definition of native title in the Native Title Act does not

require continuity, and for this reason, the Act similarly does not contemplate

what constitutes a break in continuity. However, the courts have interpreted the

Native Title Act as requiring literal continuous connection, ignoring ‘the

reality of European interference in the lives of Indigenous

peoples’.[37]

In Yorta Yorta, the High Court stated that ‘the acknowledgement

and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially

uninterrupted since

sovereignty’.[38]

Yet, as Justice North and Tim Goodwin have stated, ‘[a]lthough the Yorta Yorta test includes certain ameliorating considerations, such as

that the continuity required need not be absolute as long as it is substantial,

the ameliorating factors have not had any significant practical

effect’.[39]

What constitutes a ‘substantial interruption’ is open to

interpretation. As discussed above, the claim of the Larrakia people illustrates

the vulnerability and fragility of native title, as currently interpreted. A

break in continuity of traditional laws and customs for just a few decades was

sufficient for the Court to find that native title did not exist. However,

Justice Mansfield found that the Larrakia people ‘clearly’ existed

as a society in the Darwin area with a structure of rules and practices

directing their affairs.[40]

Although referring to the text of s 223 as the basis for its decision,

the majority in Yorta Yorta made a policy choice, although not expressly,

in favour of a restricted entitlement to a determination of native title. No

reference was made by the Court to the purpose of the Native Title Act to

redress past injustices.

A consequence of this construction of s 223 is that there is little room

to raise past injustice as a counter to the loss of, or change in, the nature of

acknowledgment of laws or the observance of customs.

Further, in cases where the claimant group has revitalised their culture,

laws and customs, a comparatively minimal interruption should not be sufficient

to defeat a claim to native title.

A shift in the burden of proof alone would not be sufficient to address the

issues around continuity of connection that arise from the Yorta Yorta test.

In order to address this injustice, I recommend legislative amendments to

address the Court’s inability to consider the reasons for interruptions in

continuity. Such an amendment could empower Courts to disregard any interruption

or change in the acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs

where it is in the interests of justice to do so.

For example, amendments could provide:

- for a presumption of continuity, rebuttable if the respondent proves that

there was ‘substantial interruption’ to the observance of

traditional law and custom by the

claimants.[41] - that where the respondent establishes that the society which existed at

sovereignty has not since then continuously and vitally acknowledged laws and

observed customs relating to land (as required by the Yorta Yorta test),

any lack of continuity or vitality resulting from the actions of settlers is to

be disregarded.[42] This could be

achieved through providing a definition or a non-exhaustive list of historical

events to guide courts as to what should be disregarded, such as the forced

removal of children and the relocation of communities onto

missions.[43]

These

amendments would complement a shift in the burden of proof.

(e) Shifting the attitudes of states and territories

Providing for presumptions and shifting the burden of proof can lead to

better outcomes for native title claimants. However, as Justice North and Tim

Goodwin observe, such provisions will

not solve the whole problem. ... Much will depend on the position taken by

State respondents. Under the reverse onus amendment provision it would be still

open to the respondents to prove lack of necessary continuity or that the

applicants do not belong to the relevant society. It remains to be seen whether

State respondents or other respondents would attempt such proof. ... Unless

State respondents react to the spirit of the change as well as to the letter,

the benefits of the reduction of cost and delay otherwise available might not

eventuate.[44]

I reiterate my belief, expressed in Chapter 2 of this Report, that there

needs to be a fundamental shift in the attitudes of the states and territories

to make these reforms work. I also believe that the Australian Government needs

to play a leadership role in encouraging states and territories to change their

behaviour, including through using its financial position and the processes of

the Council of Australian Governments.

3.4 More flexible approaches to connection

evidence

(a) Overview of connection evidence requirements

Sections 87 and 87A of the Native Title Act provide that the Federal

Court may make a consent determination of native title when it is within its

power and appropriate to do so.

As described by Justice Greenwood in the Kuuku Ya’u decision:

Section 87 ... provides that if ... the parties reach agreement on the

terms of a proposed consent order in resolution of the proceeding (the agreement

being filed in the Court) and the Court is satisfied that such orders are within

power, the Court may make orders in or consistent with those terms, if it

appears to the Court to be appropriate to do so. As to the question of power,

s 13(1) of the Act provides that an application for a determination of

native title may be made to the Court under Part 3 in relation to an area

for which there is no approved determination of native title. The Act encourages

parties to resolve such applications by negotiation, mediation and ultimately

agreement rather than contested adversarial

proceedings.[45]

In most instances, state and territory governments set requirements that

native title claimants must meet before the state or territory will engage in

mediation or negotiations. In general, state and territory governments want to

be ‘satisfied that the claim meets the evidentiary requirements of the NTA

and case law, in particular s 223 and the requirement for proof of

connection’.[46]

States and territories determine their own connection evidence requirements.

These requirements are generally set out in guidelines and other policy

documents.[47] The connection

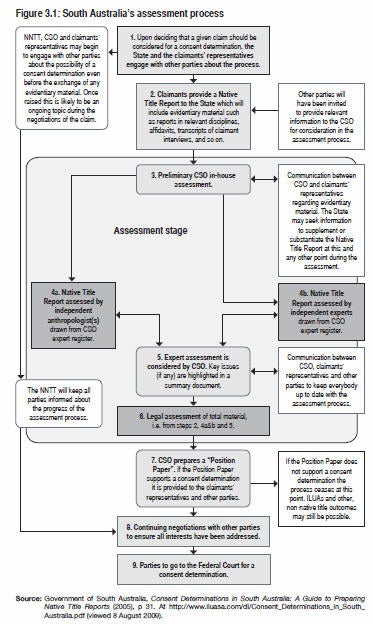

requirements differ between state and territories. Figure 3.1 sets out an

example of a state process for assessing connection material. Note that in stage

two of this process, claimants are required to provide a ‘Native Title

Report’ to the state, including evidentiary material such as reports,

affidavits and transcripts.

Figure 3.1: South Australia's assessment process

(b) What are some of the problems with connection

evidence requirements?

The connection evidence requirements imposed by states and territories can be

onerous. For example, in Hunter v State of Western Australia (Hunter),[48] North J considered that the burden upon the claimants to satisfy Western

Australia’s Guidelines for the Provision of Information and Support of

Applications for a Determination of Native Title did ‘not seem to fulfil

the purpose of ss 87 and 87A, namely, to assist in resolving applications

quickly and with minimal

cost’.[49]

He further commented:

The power conferred by the Act on the Court to approve agreements is given in

order to avoid lengthy hearings before the Court. The Act does not intend to

substitute a trial, in effect, conducted by State parties for a trial before the

Court. Thus, something significantly less than the material necessary to justify

a judicial determination is sufficient to satisfy a State party of a credible

basis for an application. ...It is to be hoped that the State will give careful consideration in future

matters under s 87 and s 87A to easing the present unnecessary burden

either placed on or assumed by native title

applicants.[50]

Similarly, the authors of a report on a Native Title Connection Workshop

facilitated by the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) and the Australian

Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) in 2007

commented that ‘in most jurisdictions the current processes have simply

relocated the evidentiary process from the Court to, largely, State or Territory

governments’.[51] This shift

is problematic, especially considering that the state and territory governments

are also the primary respondents. The unfettered ability of states and

territories to impose and unilaterally alter these requirements creates an

inequality of bargaining power.

Meeting the requirements for connection materials imposed by the states and

territories places under-resourced Native Title Representative Bodies (NTRBs)

under a heavy burden. As observed in the Native Title Report 2004,

‘connection reports require a substantial investment in terms of human and

financial resources’.[52]

Compiling connection materials is time consuming and can lead to significant

delays. The NNTT identifies ‘the timely preparation and assessment of

native title connection materials’ as critical for ensuring the steady

progress of native title applications to resolution through mediation. Yet, this

task is ‘the primary source of delay in resolving many claimant

applications’.[53]

Some have suggested that uncertainty surrounding the criteria used by the

Court in applying ss 87 and 87A further complicates this process and contributes

to the early demands for significant connection materials.

The Court may make an order under ss 87 and 87A only when ‘it is

appropriate to do so’. The concept of ‘appropriate’ has been

considered to be

‘elastic’.[54]

In Hunter, North J indicated that ‘[i]n most circumstances the

fact of agreement will be sufficient evidence upon which the Court may

act’.[55] However, as Tony

McAvoy observes, the approach:

varies depending on which of the Justices of the Court are sitting on the

matter ... on one view, it seems that nothing less than evidence meeting all the

essential elements of native title will

suffice.[56]

The Victorian Government has commented that:

so long as what is expected by the Act regarding a consent determination is

unclear, parties will feel compelled to provide, and to demand, more rather than

less, for fear of falling short of the Federal Court’s

expectations.[57]

(c) Possible solutions

(i) Legislative responses

One response to the issue identified by the Victorian Government, and others,

could be to remove the requirement that the Court must be satisfied that it is

‘appropriate’ to make the order sought by the parties (that is, to

approve their agreement). Alternatively, ss 87 and 87A could be amended to give

greater guidance as to what Courts should consider when determining whether it

would be appropriate to grant the order.

For example, the Victorian Government has suggested that an amendment to

s 87 ‘should be aimed at alerting the Federal Court to questions of

the strength and fairness of process in reaching agreement worthy of a consent

determination, and not just the evidentiary facts

themselves’.[58] This could

involve the Court being satisfied that ‘the agreement is genuine and

freely made on an informed basis by all parties, represented by experienced

independent lawyers’.[59]

It has also been suggested that the examination of appropriateness should be

confined to the consideration of whether the parties have had appropriate legal

advice.[60]

This focus on the ‘strength and fairness of process’ could have a

further advantage of providing incentives to governments to ensure that native

title claimants are adequately resourced and represented.

Introducing presumptions in favour of native title claimants may also help

alter the expectations of states and territories as to the connection materials

that native title claimants must marshall. Justice North and Tim Goodwin suggest

that:

If the law required the applicants to establish only that Indigenous people

occupied the land in question at sovereignty, State respondents would doubtless

alter their practices, rewrite the guidelines, and in many cases make agreements

for determinations of native title without delay and consequently with much

reduced cost.[61]

(ii) Policy responses

Ultimately, the solutions to the onerous connection evidence requirements

imposed by the states and territories will not lie in legislative reform alone.

A fundamental change in attitudes on behalf of states and territories is

essential to reducing the adversarial nature of the native title system, which

is reflected by the burdens placed upon native title claimants to produce

connection materials.

Rita Farrell, John Catlin and Toni Bauman observe that ‘[t]he States

and Territories have an obligation and responsibility to act in the public

interest and to be satisfied that they will be entering into agreements on

behalf of their constituents with the people who hold native title over a

particular area’.[62]

However, states and territories need to understand that it is also in the

public interest to arrive at agreements without unnecessary delay and expense.

And, as I discussed in Chapter 2 of this Report, governments also have a

responsibility to protect our rights and interests.

The legislative responses outlined above may go some way to encourage changes

in attitude and behaviour. However, the Australian Government clearly has an

important role to play in leading the process of change through non-legislative

means. The Australian Government has a great deal of financial leverage with

which to influence state behaviour and encourage the making of consent

determinations.

For example, the Australian Government could play a leading role in setting

national standards for connection requirements. These standards should be aimed

at improving the likelihood of agreements being reached and claims being

resolved with minimal delay and expense. The report of the NNTT / AIATSIS

‘Getting Outcomes Sooner

Workshop’[63] outlines some

best practice principles that could inform the development of national standards

(see Text Box 3.1).

| Text Box 3.1: Report of the ‘Getting Outcomes Sooner Workshop’ - July 2007[64] |

|

Best practice principles Basing connection processes on the following principles would significantly

Suggested policy and strategic changes A

|

3.5 Improving access to land tenure information

The progress of native title claims depends greatly on the time it takes

states and territories to release land tenure information and assess it.

Claimants invest significant human and financial resources to prepare claims.

However, the discovery of historic and extinguishing tenures after a claim has

been initiated can significantly undermine this investment in resources.

I consider that native title claimants should be able to access relevant

tenure history information at the earliest possible opportunity. The Australian

Government could facilitate this through statutory amendment and / or by use of

financial and other leverage over the policies and practices of the states and

territories. For example, state and territory governments should be required to

provide comprehensive tenure information to the native title claimants and their

representatives before requiring the native title claimants to submit connection

reports.

The appropriate party to provide tenure information is the government party.

The states and territories are responsible for land administration in their

respective jurisdictions. As they also hold the relevant information, and have

the resources to commit, the state and territory governments are in the best

position to undertake thorough tenure searches and provide tenure information to

claimants at the earliest possible opportunity.

The costs and delays described above can also be attributed to the lack of

readily accessible, comprehensive land tenure information. Improving access to

land tenure information could significantly reduce the time and costs associated

with claims processes.

In 2004, a National Summit on Improving the Administration of Land and

Property Rights and Restrictions (the Summit) was held to consider ways to

improve the supply of information concerning land and property rights,

obligations and restrictions (RORs) in Australia.

One of the issues considered at the Summit was the increasing difficulty

experienced in every jurisdiction in obtaining comprehensive information on RORs

affecting the use and / or ownership of land and property.

For example, Barry Cribb of the Department of Land Information in Western

Australia informed the Summit that there are over 180 different types of

property interests residing in some 23 custodian agencies in Western Australia

alone. An interest may be a ROR that affects the use and / or enjoyment of land.

Types of interests include easements and environmental, cultural, planning,

building and health interests. Mr Cribb raised a number of concerns including

that:

- the majority of property interests are not held in the Torrens Register

- there is no definitive source of interests in land

- there is no mechanism for the recognition or discovery of new

interests.[65]

I

consider that there is a further deficiency with the current level of access to

tenure information. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have varying

degrees of access and control of at least 20% of the Australian

continent.[66] However, there is

currently no baseline information that defines on a national basis the lands,

waters, and tenures that make up the Indigenous estate.

At the Summit, Margaret C Hole AM considered that ‘it is desirable to

provide a registration system that discloses all things relating to title

including ownership, mortgages, leases, easements, covenants, planning

requirements, zoning, geographical restrictions, weather patterns, demographics

etc’.[67]

Since 2004, considerable work has been undertaken to address the concerns

raised at the Summit. This includes a project initiated by the National Land and

Water Resource Audit with the intention of creating a land tenure data set with

Australia-wide coverage.[68]

Further, the NNTT, in collaboration with other Australian Government

agencies, is pursuing the development of a National Information Management

framework for land tenure through ANZLIC – the Spatial Information

Council, which is the intergovernmental body for spatial

information.[69]

I support the establishment of a comprehensive national information

management database that co-ordinates national and jurisdictional land tenure

information. To improve accessibility, this database could be made available

online.

States and territories should be encouraged to provide a full inventory that

maps the various tenures across their jurisdictions to contribute to such a

database. This database should include native title rights and interests and

other forms of Indigenous tenure, and lands where tenure resolution is

required.[70]

An online national land tenure database would significantly increase the

ability of claimants to access information and reduce pressure on their

resources.

3.6 Streamlining the participation of non-government

respondents

There are frequently a large number of parties to native title proceedings.

This can lead to unnecessary delays, costs and the frustration of settlement

efforts.

The Australian Government has acknowledged that the numbers of respondent

parties in native title claims is unacceptable. In Australia’s comments to

the United Nations Human Rights Committee, the Government said:

The involvement of a large number of non-government respondent parties in

native title claims contributes to the complexity, time and cost of claims.

While the interests of non-government respondents need to be considered to

ensure sustainable outcomes, respondents should be concerned to clarify the

interaction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous property rights, not to expend

public resources on determining whether native title

exists.[71]

The participation of respondents in native title proceedings must be managed

effectively. Addressing the problems associated with excessive party numbers and

improving the processes involved to become a party is critical to improving the

efficiency of the native title system.

I believe that the current balance between the representation of native title

and non-native title interests is poorly struck. Consideration needs to be given

to a number of matters concerning the participation of respondents in native

title claims, including:

- the role of state and territory governments in representing respondent

interests - party status

- processes for removing parties

- representative parties

- funding for respondent parties.

(a) The role of state and territory

governments

The role of governments in a native title claim is primarily to represent the

interests of the community and to test the validity of the claim.

Consequently, South Australian Native Title Services comments that:

Amendments should provide that the Federal Court should rely on the first

respondent, being the State Government, to represent all respondent interests

whose interests are gained from a grant of rights from the State...The State

under legislation manages for example the Fishery or the Mineral resources for

the public generally and as such, the State as the grantor of such interests is

best placed to represent all persons holding such interests in the native title

context.[72]

Consistent with this, Daniel O’Dea of the NNTT stated:

Bearing in mind that the State goes to great lengths to ensure that all

extant interests are listed in schedules to all determinations and that those

interests will prevail over the native title interests to the extent of any

inconsistency, it is arguable there is no real need for current holders [of

those interests] to actively

participate.[73]

Given the role that state and territory governments play, I agree that the

involvement of so many respondents in native title claim proceedings should be

reappraised. Options for reform are discussed below.

(b) Party status

To streamline the participation of non-government parties, the Native Title

Act should include stricter criteria that respondents must meet in order to

become and remain parties to native title proceedings.

| Text Box 3.2: Section 84 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) |

|

Section 84 of the Native Title Act identifies who can become a party Section 84 of the Native Title Act provides an extremely broad test Amendments made to s 84 in 2007 included some positive |

The following options should be considered.

The threshold for joinder as a party could be amended to reflect more

traditional tests for standing in civil proceedings, such as the ‘special

interest’ test under general

law[77] or the ‘person

aggrieved’ test under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review)

Act 1977 (Cth).[78]

Another

alternative would be to require the party seeking to be joined to satisfy

criterion set out in Order 6 Rule 8 (Addition of Parties) of the Federal Court

Rules, which includes that joinder of the person ‘is necessary to ensure

that all matters in dispute in the proceeding may be effectually and completely

determined and adjudicated upon’.

A further option is to revisit the criteria in ss 84(3) and 84(5). The

following persons are among those who are entitled to be parties to a native

title claim:[79]

- a person whose interest, in relation to land or waters, may be affected by a

determination in the

proceedings[80] - any person who, when notice of a native title claim is given, holds a

proprietary interest that is registered on a public register in relation to any

of the area covered by the

application.[81]

Such

persons could be required to show that their interests are likely to be substantially affected by a determination in the proceedings. The Native

Title Act could provide that a person claiming that their interests are

substantially affected must make an application to the Court before they can be

joined as a party.[82] The

application should set out how the person’s interests are likely to be

substantially affected if the Court were to make the determination sought. The

claimant and the primary respondent should then have an opportunity to make

submissions to the Court.

Alternatively, the Government could explore options to enable a reduced form

of participation in native title proceedings for certain respondents, such as

those who may seek only to be added as a party to ensure that their rights and

interests are preserved under any final determination.

It may not be necessary to afford full procedural and other rights to such

parties. A tiered system of participation may allow for certain procedural

matters to be dealt with more expeditiously by only requiring the consent of the

‘key players’ to the proceeding, usually the native title claimant

and the government party.

If these amendments are made, the Court would retain the discretion as to

whether to join the person as a party. However, raising the threshold for

addition as a party, as well as requiring the proposed respondent to carry the

burden of proof in establishing why they should be added, would contribute to

the more effective management of the number of parties to claims.

In particular, claimants and primary respondents would have a firmer basis on

which to challenge the addition of parties whose interests appear peripheral or

adequately represented by other parties, together with a formal opportunity to

make that challenge before the Court.

(c) Removal

of parties throughout proceedings

Many people who become parties when a native title claim is first made may

lose their relevant interest as the claim progresses. This might be due to

changed circumstances over the intervening years or due to the fact that

extinguishment is often not considered until late in the proceeding.

The Native Title Act already provides for the removal of parties from

proceedings. Section 84 of the Act details a number of ways a party may be

removed from the proceeding, such as through leave of the Court after the

proceeding has begun.[83] Section 84(9) also states that the Court is to consider making an order

that a person cease to be a party if the Court is satisfied that the person no

longer has interests that may be affected by a determination in the proceeding.

However, the Court’s powers to remove parties are not used regularly or

consistently throughout native title proceedings. The most recent amendments to

the Native Title Act give the Federal Court ‘a central role’ over

the management of native title

proceedings.[84] Complemented by

focused amendments to provisions related to respondent parties, this power could

enable proceedings and agreements to progress more efficiently.

The negotiation of the Thalanyji consent determination provides a practical

example of where the Court’s power to remove parties has been utilised:

the NNTT, in co-operation with the registrars of the Federal Court, sought

the making of orders by His Honour, essentially in the character of a springing

order, which required all parties, except specified parties who were actively

participating, to notify the Court of their intention to remain a party within a

specified time. Failure to do this would lead to those parties losing that

status. Due to the number of parties, the process involved a great deal of

correspondence and telephone communication and was extremely time-consuming.

However, in the end, in the Thalanyji matter, a significant number of parties

(approximately one third) chose to withdraw voluntarily and, subsequent to the

springing orders being made, all the remaining parties consented to the

determination in the form proposed to the

Court.[85]

This example demonstrates the benefits of requiring parties to advise the

court on a periodic basis how their interests continue to be affected by the

proceedings in order to remain a party. I consider that the Native Title Act

should be amended to require this. Such a process may assist with managing the

current numbers of parties to native title proceedings.

Specifically, ensuring a regular ‘clean up’ of the party list

could be achieved through amendments to s 84(9) of the Native Title Act.

The Court should be required to regularly review the party list for all active

native title proceedings and, where appropriate, require a party to show cause

for its continued involvement.

The NNTT may also have a role to assist the

Court, drawing on its expertise and access to information necessary to undertake

such a review. The NNTT could also provide advice to the Court about parties

that no longer hold the necessary interest to maintain party

status.[86]

If the above proposals to raise the threshold for party status were to be

adopted, this could encourage the more effective utilisation of the

Court’s power to remove parties. Above all, it would enable claimants and

respondents to more effectively challenge the ongoing involvement of parties

whose interests have faded or disappeared during the life of the claim.

(d) Exploring

the potential for using representative parties

The use of representative parties may also assist in the management of the

number of respondents to native title claims.

Representative parties can already be used in Federal Court proceedings in a

number of circumstances. In particular, Order 6, Rule 13 of the Federal Court

Rules deals with representative respondents. It enables the Court, at any stage

in proceedings, to appoint any one or more of the respondents to represent

others with the same interests.

Further consideration could be given to how

this rule or a similar rule could be used to achieve a more rational management

of parties in native title proceedings. The Australian Government could also

explore legislative amendments to facilitate the appropriate use of

representative respondents to streamline native title litigation.

(e) Improving transparency in respondent funding

processes

Currently, respondents may be funded by the Commonwealth under the

‘respondent funding scheme’ to participate in native title

proceedings.[87] The

Attorney-General may make guidelines that are to be applied in authorising the

provision of assistance.[88]

I consider that greater transparency in the implementation and operation of

this funding scheme is required.

In 2006, the Australian National Audit Office observed that the

Attorney-General’s Department ‘is unable to evaluate either the

effectiveness of the Respondents Scheme at either the individual grant level or

the contribution the programme is making to the larger Native Title System

outcome’.[89]

In particular, little information is available regarding which parties are

being funded to participate in the proceedings, how the Attorney-General’s

funding guidelines (the

Guidelines)[90] are being applied

and whether the ongoing funding of particular parties is appropriate.

The Native Title Act and the Guidelines need to ensure greater transparency

in the funding process.

For example, the Guidelines allow for the withdrawal of funding in certain

circumstances, including where the respondent fails to act

reasonably.[91] Yet, the reference

to a failure to act reasonably is not defined or clarified. It might be

appropriate for s 213A or the Guidelines to be amended to stipulate that

recipients of funding under the scheme must agree to abide by standards applied

to the Commonwealth and its agencies under the Commonwealth model litigant

guidelines appended to the Legal Service

Directions.[92] Section 213A or the

Guidelines could also stipulate that failure to comply with these standards may

result in withdrawal of funding.

Further, the Guidelines or s 213A could be amended to articulate a

mechanism by which other parties or the appointed mediator can apply to the

Attorney-General to have a party’s funding withdrawn where a respondent

inappropriately undermines the conduct or resolution of a claim. This could

occur, for example, where the appointed mediator is of the view that the party

has refused to make a bona fide and reasonable endeavour to resolve the

dispute.[93]

3.7 Promoting broader and more flexible native title

settlement packages

(a) Background

The challenge is ... to effectively engage ... and to transform the potential

wealth that participation in resource extraction may bring, into a sustainable

social and economic future for those communities most impacted by the resources

boom.[94]

In this section, I

consider the changes to law and process that are required to promote broader and

more flexible native title settlement packages to support our social and

economic development.

The 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act introduced a legal framework and

process for the negotiation of ILUAs between native title holders and others

about the use and management of lands, waters and resources. This

agreement-making framework has gone some way to encourage negotiated outcomes

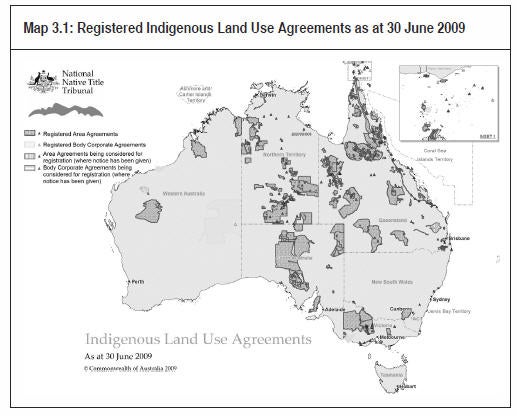

and avoid costly litigation. As at 30 June 2009, 389 ILUAs had been registered

with the NNTT.[95] See Map 3.1 for

further information on ILUAs across Australia.

Map 3.1: Registered Indigenous Land Use Agreements as at 30 June

2009

Since 1996, Rio Tinto alone has signed nine major development agreements and

negotiated more than 100 exploration agreements across Australia. This has

resulted in a commitment of approximately $1.4 billion in social and economic

investment over the next 20 years to Indigenous

communities.[96]

However, the Government is concerned that the benefits accruing to Indigenous

interests under native title agreements are not adequately addressing the

economic and social disadvantage faced by Indigenous

communities.[97] It has been

estimated that only 12 of the hundreds of agreements that have been negotiated

between traditional owners and industry provide substantial benefits to

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and exhibit principles embodying

best practice in

agreement-making.[98]

Further, agreements often deliver little in terms of cultural heritage

protection or environmental management beyond what is already available under

general legislation, and often require traditional owners to surrender their

native title rights and

interests.[99]

As discussed in

Chapters 1 and 2 of this Report, the Government is seeking to build partnerships

with Indigenous communities through ‘equitable

agreements’.[100]

Recent amendments to the Native Title Act enable the Federal Court to make

determinations that cover matters beyond native

title.[101] The Native Title

Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) clarifies that the Court can make orders that

reflect agreements made by the parties.

There are a number of matters that could be included in such agreements,

including economic development opportunities, training, employment, heritage,

sustainability and existing industry

principles.[102]

The power for the Court to make orders about matters other than native title

may also provide a mechanism for the ‘alternative recognition of

traditional ownership’ (discussed in section 3.2, above), even in

cases where native title was not determined to exist.

These reforms can ensure that agreements are formally recognised and more

readily enforceable. This approach could also encourage parties to negotiate

native title claims more laterally, creatively and flexibly, rather than to

simply negotiate on an ‘all or nothing’ basis in relation to the

determination of native title.

For example, the South Australian Native Title Services commented as

follows:

Depending on the terms of the agreement, native title claim groups who are

either unable to establish native title by agreement, or are willing to

surrender native title to avoid the risk of a determination of no native title,

could secure other orders as to the terms of an agreement reached i.e.

recognition of traditional rights, transfers of land

etc.[103]

The ability for the

Court to make orders concerning non-native title outcomes may provide a

mechanism whereby agreement-makers are able to coordinate the multiple and

complex agreements that they are party to under various legal regimes, including

lands rights and heritage legislation. This would allow these agreements to

provide comprehensive strategic directions for Indigenous communities.

It is positive that the Government is encouraging parties (including states

and territories) involved in native title claims to work together to reach

agreements with broad and beneficial outcomes. However, the ‘broader

settlement’ framework needs to be accompanied by amendments to address

inadequacies and inequality in the Native Title Act.

There are many ways that agreement-making processes could be improved,

including:

- strengthening procedural rights and addressing concerns with the future acts

regime - amending the definition of native title in s 223 to include rights and

interests of a commercial nature - using long-term adjournments to support agreement-making

- developing the capacity of communities to engage in effective

decision-making.

(b) Strengthening procedural rights and the future

acts regime

The future acts regime is an essential element of the Native Title Act. Its

strengths (or weaknesses) directly impact on the way parties behave in

negotiating agreements. The operation of the regime is integral to good

agreements which benefit the parties – a priority of this Government. I

recommend that the Government consider how the future acts regime can be amended

to strike a better balance between native title and non-native title interests

and create stronger incentives for the beneficial agreements the Government

wants to see.

The right to negotiate regime is also a crucial element of the Native Title

Act. It should not be construed

narrowly.[104]

| Text Box 3.3: Procedural rights |

|

The right to Part 2, Division 3 of the Native Title Act makes provision for registered Generally, a government has two options to validly do an act that attracts The future acts The Native Title Act seeks to protect native title rights by prescribing A future act is an act done after 1 January 1994 (the date of the |

However, the future acts regime in its present form has been the subject of

international criticism.[107] And,

as Sarah Burnside notes, recent decisions have illustrated the limitations of

the right to negotiate, stemming from the terms of the Native Title Act and the

way they have been interpreted by the NNTT and the Federal

Court.[108]

The following

reforms could address some of these limitations.

(i) Improving procedural rights over offshore

areas

Procedural rights over the sea and offshore areas are limited, with the right

to negotiate not being available for acts occurring below the high water

mark.[109] However, the Court has

considered that there is native title in offshore areas and this Government has

recognised that native title can exist up to 12 nautical miles out to

sea.[110] This recognition seems

inconsistent with the limitations on procedural rights over the sea. This

situation could be improved by the repeal of s 26(3) of the Native Title

Act.

(ii) Addressing compulsory acquisition and

extinguishment

Section 24MD(2)(c) of the Native Title Act currently states that

compulsory acquisition extinguishes native title. As originally enacted,

s 23(3) of the Native Title Act stated that acquisition itself does not

extinguish native title, only the act done in giving effect to the purpose of

the acquisition that led to extinguishment. There appears to be no policy

justification for the current position. I consider that it would be appropriate

for s 24MD(2)(c) be amended to revert to the wording of the original

s 23(3).

(iii) Strengthening the requirement to negotiate in

good faith

Parties are prevented from resorting to an arbitral body (usually the NNTT)

for a period of six months from the issue of a notice that the government

intends to grant a mining

tenement.[111] During this

negotiation period, s 31 of the Native Title Act obliges the parties

involved to negotiate in good faith.

In Chapter 1, I reviewed the Full Federal Court’s decision in FMG

Pilbara Pty Ltd v Cox (FMG

Pilbara).[112] It is clear

from this decision that it is difficult for claimants to establish that a mining

company has not acted in good faith.

Several problems are evident in the wake of the FMG Pilbara decision,

which deserve the close attention of the Australian Government.

Reconsidering time periods for negotiations

The Native Title Act imposes a severe time constraint on mining negotiations.

Six months is a very short period for the establishment of negotiations

protocols, assembly of relevant information, presentation of proposals,

discussions amongst native title parties and their advisers, the making of

offers and counter-offers and so on. This is particularly so in areas such as

the Pilbara where the abundance of mining activity creates huge pressures on

under-resourced NTRBs. For situations where no claim is on foot, a credible

application has to be prepared, lodged and registered within the first four

months after the notice period.

The same statutory time limits apply regardless of the breadth of

negotiations. In FMG Pilbara, the parties had sought to conclude

an agreement on a ‘whole of claim’ basis. This not only sought to

make efficient use of time and resources, but offered the mining company the

prospect of much greater long-term resource security. Such negotiations are

necessarily far more complex than the grant of a single mining tenement. In this

case, negotiations with one of the native title parties had not proceeded far

past the conclusion of a preliminary protocol agreement on how the planned

comprehensive negotiations were to be conducted. I find it difficult to agree

with the Full Federal Court’s assessment that six months ‘ensures

that there is reasonable time to enable those negotiations to be

conducted’.[113]

Under such time pressures, miners can drive a very hard bargain on questions

such as compensation, knowing that an arbitral body cannot make a mining grant

conditional on a royalty or similar

payment.[114]

The same six month time limit is also imposed regardless of whether the

parties have negotiated before and have, for example, a process agreement in

place to regulate their talks.

The brevity and uniformity of time limits under the right to negotiate need

to be reviewed. Alternatively, s 31 could be amended to require parties to

have reached a certain stage before they may apply for an arbitral body

determination.

Shifting the onus of proof

In relation to s 31, the burden of proof for establishing the absence of

good faith negotiations is on the native title party. Shifting the onus onto the

proponents of development, to positively show their good faith, is likely to

alter their behaviour during negotiations and alleviate some of the current

unfairness embedded in the right to negotiate process. It may improve the

quality of the offers made by miners and discourage conduct such as bringing

negotiations to an end mid-stream and seeking arbitration without notice to the

native title parties.

Revisiting the onus of proof offers another means for improving the fairness

of the right to negotiate procedure and is likely to encourage

agreement-making.

Allowing arbitral tribunals to impose royalty

conditions

Agreements struck during the six month good faith negotiation period

regarding a mining act or a compulsory acquisition can include provisions for

royalties or profit sharing.[115]

Pursuant to s 38, if an agreement is not reached and the matter is

referred to the NNTT for arbitration, the NNTT must make a determination either

that the act:

- must not be done

- may be done

- may be done subject to conditions to be complied with by any of the

parties.[116]

However,

under s 38(2), the NNTT cannot a make a determination that an act may be

done subject to conditions of profit-sharing or the payment of

royalties.[117]

When the drafters of the Native Title Act in 1993 denied the NNTT the

capacity to include a royalty-style condition in an arbitral determination,

their decision was premised on a certain prediction about the balance of power

under the right to negotiate. As events have transpired, the drafters clearly

over-estimated the impact on miners of a six-month hiatus in the approvals phase

of a mining project. The premise of the drafters’ decision has been

falsified and that has seriously diminished the quality of outcome typically

obtainable by native title parties from the right to negotiate.

As Tony Corbett and Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh observe, this creates a

‘fundamental

inequality’[118] and

‘places native title holders and claimants under considerable pressure to

conclude an agreement within the negotiation

period’.[119]

The Victorian Government has recommended amendments to the Native Title Act

to allow ‘the arbitral body to make determinations about the amount of

profits, income and productions that were the subject of

negotiations’.[120] I also

believe that s 38(2) should be reconsidered.

(c) Recognition of commercial rights

The Government has stated that it considers that Indigenous communities

should be using their native title rights to leverage economic

development.[121] The link between

native title and economic development has been further acknowledged by the

Government through its decision to include native title in its Indigenous

Economic Development

Strategy.[122]

Agreement-making can be an important vehicle for social and economic

development. However, the Native Title Act does not clearly provide for the

recognition of commercial rights.

This may prevent a community from being able to use native title rights to

support their economic development aspirations.

Courts have often appeared to take the view that customary Indigenous laws

and customs for the purpose of native title do not include commercial activity.

This perception has created distinction between customary rights and commercial

rights.[123]

There is growing evidence that this distinction is neither necessary nor

accurate. For example, in the Native Title Report 2007 I considered the

experience of the Gunditjmara people in Victoria who were able to prove that

their ancestors had established an ancient aquaculture venture. The Federal

Court recognised their native title rights and the Gunditjmara peoples are now

using these rights to re-establish commercial eel

farming.[124]

Further, the high evidential bar for establishing the relevant bundle of

native title rights excludes or significantly limits the prospect of commercial

rights being recognised. For example, in Yarmirr v Northern Territory at first instance, in response to evidence of trade with neighbouring tribes

in clay, bailer shells, cabbage palm baskets, spears and turtle shells, Olney J

held:

The so-called ‘right to trade’ was not a right or interest in

relation to the waters or land. Nor were any of the traded goods

‘subsistence resources’ derived from either the land or the

sea.[125]

His Honour also observed that evidence of trade with Macassan fishermen

related only to the gathering of trepang, but did not assist in establishing

rights or interests in relation to other resources of the

sea.[126]

This is a very narrow approach to the characterisation of rights. In addition

to an uninterrupted practice of commercial fishing, his Honour appeared to