1 Social justice - Year in review

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Machinery of Government changes

- 1.3 The 2014 Budget

- 1.4 Leadership, representation and engagement

- 1.5 Constitutional recognition

- 1.6 Indigenous Jobs and Training Review

- 1.7 Closing the Gap

- 1.8 Stolen Generations

- 1.9 International developments

- 1.10 Australian Human Rights Commission complaints

- 1.11 Conclusion

1.1 Introduction

At the beginning of this reporting period, we were in the midst of the 2013 federal election. During the campaign, then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott pledged to be the nation’s ‘Prime Minister for Aboriginal Affairs’.[11] He intended to translate his long-standing concern for Australia’s First Peoples into action, placing Indigenous Affairs at the heart of the Coalition government’s agenda.

As this report was being prepared, the Coalition government took office, which provides an opportunity to reflect on its progress to date and on the challenges that lie ahead.

On 18 September 2013, as the new Cabinet was sworn in, responsibility for the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policies, programs and services was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C). The status of Indigenous Affairs was elevated with a dedicated Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Coalition Senator Nigel Scullion, and a Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister on Indigenous Affairs, Coalition MP Alan Tudge. These appointments are concrete evidence of the Prime Minister’s commitment to achieve positive and practical change in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Prior to being elected, then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott stated:

I am reluctant to decree further upheaval in an area that’s been subject to one and a half generations of largely ineffectual ‘reform’.[12]

As with any change of government, our first year under the Coalition government has been marked by a flurry of activity.

For Indigenous Affairs, it has been a year characterised by deep funding cuts, the radical re-shaping of existing programs and services, and the development of new programs and services.

This has coincided with the government commissioned reviews of Indigenous Training and Employment Programs[13] and of Australia’s welfare system.[14] These reviews, in addition to the government’s budgetary measures, have the potential to impact greatly on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It is not clear how these complement each other or what bearing these changes have on other areas of government. Contrary to the Prime Minister’s statement when leader of The Opposition, we are now witnessing one of the largest scale ‘upheavals’ of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

These measures, combined with the hesitation of government to set a date for a referendum on constitutional recognition, and the impact of various government reviews, has created an atmosphere of uncertainty for our peoples.

This is compounded by the way Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are represented at the national level, which is in a state of flux. New advisory arrangements have been created and existing representative structures have been defunded.

This lack of clarity and muddled narrative is deeply worrying.

This chapter also reports on a number of developments at the national and international level concerning Stolen Generations and Australia’s participation in United Nations mechanisms.

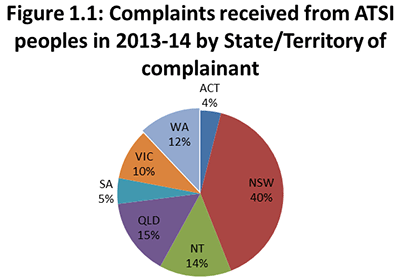

As I have done in previous reports, I will provide data on complaints received from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by the Australian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) and report on the progress of the Close the Gap campaign over the past year.

1.2 Machinery of Government changes

The past year has seen a significant restructuring of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policies, programs and service delivery at the federal level.

Prior to the election, eight federal government departments were primarily responsible for Indigenous Affairs:

- Department of Attorney-General

- Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

- Department Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

- Department of Health and Ageing

- Department of Industry, Innovation, Climate Change, Science, Research and Tertiary Education

- Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport

- Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.

These departments administered 26 programs, which drove more than 150 Indigenous-specific initiatives and services. Many of these departments have since been restructured and renamed.

The consolidation of these policies, programs and service delivery into PM&C seeks to streamline arrangements, reduce red tape and prioritise expenditure to achieve practical outcomes on the ground.[15]

This move is intended to address some of the structural and logistical problems faced when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services are delivered through multiple agencies.

The transfer of the program delivery role to a ‘central agency’ such as PM&C, means a significant change in the way the department operates. I am informed that the bulk of Australian Government staff involved in delivering Indigenous programs and services, in regional and remote locations throughout Australia, will remain in their locations but will be part of PM&C. We now have a ‘central agency’ operating a regional network and all of its attendant issues.

The transfer of approximately 150 programs and activities, along with 2000 staff means that PM&C is now dealing with about 1440 organisations and nearly 3040 current funding contracts.[16]

It will take time to build the administrative systems, acclimatise staff in the new structure within PM&C, and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, already cynical and fatigued by change, to have confidence in the competence of those implementing these new arrangements.

Information on the transfer arrangements has been scant with minimal involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. There was little or no consultation with those working on the ground about which programs and activities were best kept together, or which departments were best placed to administer them.

There were significant negotiations between departments before these arrangements were finalised. As it stands, it is difficult to understand the logic behind the basis for the transfer of some programs and activities. For example, the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health will remain with the Department of Health, however, petrol sniffing initiatives previously funded in that department have been transferred to PM&C.

The process of transferring those 150 programs and activities into PM&C has caused immense anxiety amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. This, in part, can be attributed to the uncertainty of which programs would be transferred and who would be administering them.

In the Social Justice and Native Title Report 2013, I reflected on the 20 years of work by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioners and I was reminded how circular and repetitive approaches to Indigenous Affairs can be.

In 2004, upon the abolition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, the Coalition Government implemented a complex set of reforms, which became known as the ‘new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous Affairs’ and included:

- transferring responsibility for the delivery of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific programs to mainstream government departments

- the adoption of whole-of-government approaches, with a greater emphasis on regional service delivery

- the establishment of new structures, such as the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC) to coordinate policy nationally and Indigenous Coordination Centres (ICCs) at the regional level

- a process of negotiating agreements at the local and regional level through Shared Responsibility Agreements (SRAs) and Regional Partnership Agreements (RPAs).[17]

At the launch of the Social Justice Report 2005 my predecessor, Dr Tom Calma remarked:

One of the most basic problems of the new arrangements – a lack of information delivered down to the local level for both bureaucrats who are supposed to be implementing the new approach and most crucially for communities.[18]

Sadly, the words spoken above by Dr Calma are as relevant to the 2014 machinery of government changes as they were nearly ten years ago.

1.3 The 2014 Budget

We must remember that despite times of fiscal austerity Australia is an enormously wealthy nation...[19]

- Mick Gooda and Kirstie Parker, 12 February 2014

On 13 May 2014, the Australian Government introduced the 2014-15 budget (the Budget) into Parliament. This Budget was notable for cuts across almost all areas of public spending in order to meet the incoming government’s commitment to move rapidly towards eliminating federal budget deficits.

(a) Indigenous Advancement Strategy

The Budget confirmed the above mentioned consolidation of all Indigenous specific programs through the introduction of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS).

The IAS aims to ‘improve the lives’ of our peoples through streamlined arrangements of programs and service delivery across education, employment, culture and capability, safety and wellbeing, by bringing these areas under the coordination of PM&C.[20]

The IAS also involves a range of administrative changes, including:

- dealing with approximately 1440 organisations with around 3040 current funding contracts

- establishing a new regional network

- new funding administration arrangements, where there will be changes to incorporation requirements and application processes including:

- open competitive grants rounds

- targeted or restricted grant rounds

- direct grant allocation processes

- a demand-driven process

- one-off or ad hoc grants that do not involve a planned selection process, but are designed to meet a specific need, often due to urgency or other circumstances.[21]

The government committed $4.8 billion over four years to the IAS, in addition to $3.7 billion allocated through National Partnership Agreements, Special Accounts and Special Appropriations to Indigenous-specific funds now administered by PM&C.

Importantly and unfortunately, this meant $534.4 million was cut from Indigenous programs from the PM&C and the Department of Health over five years,[22] including:

- $15 million from the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples (its entire forward funding)[23]

- $3.5 million from the Torres Strait Regional Authority[24]

- $9.5 million from the Indigenous Languages Support Program.[25]

Senator Scullion reportedly promised that there would not be ‘any impact on the ground to frontline services’.[26] Rather, the savings will be wholly achieved through the rationalisation of Indigenous programs and the cutting of red tape within PM&C.

This involves rationalising the previous 150 Indigenous programs and activities into five streamlined programs or funding streams of the IAS, set out below in Text Box 1.1.[27]

Text Box 1.1: The Indigenous Advancement Strategy Programmes[28]

Jobs, Land and Economy Programme

This programme aims to get adults into work, foster viable Indigenous business and assist Indigenous people to generate economic and social benefits from land and sea use and native title rights, particularly in remote areas.

Children and Schooling Programme

This programme focuses on getting children to school, improving education outcomes including Year 12 attainment, improving youth transition to vocational and higher education and work, as well as, supporting families to give children a good start in life through improved early childhood development, care, education and school readiness.

Safety and Wellbeing Programme

This programme is about ensuring the ordinary law of the land applies in Indigenous communities, and that Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians.

Culture and Capability Programme

This programme will support Indigenous Australians to maintain their culture, participate equally in the economic and social life of the nation and ensure that Indigenous organisations are capable of delivering quality services to their clients.

Remote Australia Strategies Programme

This programme will address social and economic disadvantage in remote Australia and support flexible solutions based on community and government priorities.

These five broad programs of the IAS are to be implemented by the new PM&C Regional Network (the Network).

The Network aims to ‘deliver demonstrable improvements in school attendance, employment and community safety’ and ensure that decisions are made closer to the people and communities they affect.[29]

The Network will be headed by a National Director and supported by a Deputy Director for Northern Australia.

The IAS was established in the first quarter of the current financial year. The government mandated a 12 month transition period in an effort to achieve seamless service delivery and give service providers and communities time to adjust to the new arrangements.[30]

I am informed that most existing funding agreements are being honoured.[31]

In the transition period, organisations with funding agreements which have expired since the Budget, or are due to expire by June 2015, are being given extensions of six to 12 months in order to facilitate a smooth transition.

(b) Mainstream budget measures

It is disappointing that savings from the rationalisation of Indigenous programs and services will not be reinvested into Indigenous Affairs and Closing the Gap initiatives. In addition to the IAS, health funding for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific programs, grants and activities will be refocused under the ‘Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme’.[32] This is part of drawing up a new methodology for funding Indigenous health, flagged by the Budget.[33] The methodology needs to align with the Health Plan, and the government must engage with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health sector during this process.

The Budget outlines that savings from health programs will be directed to the new Medical Research Future Fund, while other savings from the restructure will be ‘redirected by the Government to repair the Budget and fund policy priorities’.[34]

On the other hand, the following new measures relating to Indigenous Affairs were included in the Budget, set out in Text Box 1.2

Text Box 1.2: New spending in Indigenous Affairs[35]

|

Budget expense measures

|

Program

|

Amount

|

|---|---|---|

|

Prime Minister & Cabinet

|

Clontarf Foundation Academy

|

$13.4m

|

|

Community Engagement Police Officers in the Northern Territory

|

$2.5m

|

|

|

Outback Power

|

$10.6m

|

|

|

Permanent Police Presence in Remote Indigenous Communities

|

$54.1m

|

|

|

Remote School Attendance Strategy — extension

|

$18.1m

|

|

|

Support for the Northern Territory Child Abuse Taskforce – Australian Federal Police

|

$3.8m

|

|

|

Education

|

AIATSIS - Digitisation of Indigenous cultural resources

|

$3.3m

|

|

Remote Indigenous Students Attending Non-Government Boarding Schools

|

$6.8m

|

|

|

Health

|

Indigenous teenage sexual and reproductive health and young parent support

|

$25.9m

|

|

Social Services

|

Income Management – one year extension and expansion to Ceduna, South Australia

|

$101.1m

|

It is concerning that the largest allocation of new Indigenous spending in the Budget was to extended income management in existing locations for one year.[36] Income management has been extended for one year in the Northern Territory, metropolitan Perth, Western Australia’s Kimberley region, South Australia’s Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, as well as Laverton Shire and Ngaanyatjarra Lands.[37] Income management has also been expanded to Ceduna, South Australia, since 1 July 2014.[38]

(c) Indigenous Advancement Strategy – some challenges

The move to rationalise 150 programs and activities to five is to be applauded.

I believe that streamlining 150 small programs into five large programs provides greater flexibility for communities. It could provide more scope to develop on the ground responses to the issues that confront our communities on a daily basis. In other words, it is the first step away from a ‘one size fits all’ mentality that has, for so long, confounded our people.

If done right, this move to a smaller number of programs has the potential to achieve the Australian Government’s stated aims of reducing red tape and cutting wasteful spending on bureaucracy. This, in turn, could also translate to a greater share of funds being provided on the ground.

However, the challenges are wide and varied. Bringing about budget cuts in the order of $400 million over the next four years will be an immense undertaking. This figure alone tells us it is likely many organisations will be defunded through this process, with corresponding loss of services to the community. These losses will be even more severe if any new services or activities are funded during this time.

There is widespread concern amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations about the lack of detail on how the proposed measures will be implemented and what their impact will be.

Restructuring programs and funding processes, which will affect around 1400 organisations with over 3000 funding contracts, is complex and stressful. It is also time consuming and calls for a highly skilled and culturally competent workforce that is cognisant of the magnitude of this task. It requires an effective communication strategy and a transition process that is open, transparent and easily understood. Most importantly, it will require respectful engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The government should be open to extending the transitional period in the event that the tasks outlined above present challenges that were not anticipated when the 12 month timeframe was set.

(d) Other budget measures – some concerns

In addition to what I have outlined above, there have been some added budgetary measures which will impact language, legal and family violence services that are provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

(i) Indigenous languages

The inclusion in the Budget of cuts to the Indigenous Languages Support Program is regrettable in light of the 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report, which found that, of the 145 Indigenous languages still spoken in Australia, 110 are critically endangered and the rest ‘face an uncertain future if immediate action and care are not taken'.[39]

(ii) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services

The Australian Government announced in December 2013 that the broader legal assistance sector (including Community Law Centres) was to lose $43.1 million over four years, from 2014-15.

Notably, this includes a $13.4 million cut to the Indigenous Legal Aid and Policy Reform Program.[40] These cuts will take effect from 1 July 2015. This program funds Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (ASTILS), and community controlled not-for-profit organisations that provide legal assistance as well as community legal education, prison, law reform and advocacy activities for our peoples.

The government indicated that any cuts to ATSILS would only affect policy reform and advocacy work, not frontline legal services. However, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS) has highlighted that the value of Indigenous legal services is that they provide ‘strategic and well-informed advice about effective law and justice policies’ to governments, leading to a reduction in the incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[41] The NATSILS has also stated concerns that the withdrawal of funding for law reform and advocacy positions will result in solicitors and legal officers, currently providing frontline services, assuming this work.

The NATSILS Chair, Mr Shane Duffy, predicted that without an advocacy capacity ‘more people are going to end up in prison, it’s as simple as that’.[42]

According to NATSILS, evaluations in recent years have suggested that ATSILS are ‘meeting their primary objectives to improve the access of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians to high-quality and culturally appropriate legal aid services’.[43]

The importance of having culturally competent legal services is demonstrated by the work of the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service.

Text Box 1.3: Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service (CAALAS)[44]

CAALAS was acting for a number of people from a remote community which had been the scene of a serious conflict between two families. The conflict had erupted over a death in Alice Springs, and had resulted in numerous riot and assault charges. With members of the two families bailed or summonsed to attend a remote court on the same day, tensions were high and further conflict ensued. A CAALAS field officer, a Walpiri woman with excellent knowledge of the community and family connections, liaised with the court. She arranged for the list to be split between two days, so that family members could attend court separately and peaceably.

The case demonstrates how CAALAS’s knowledge of community and of cultural responses to specific situations can have a positive and direct impact on service delivery, adding real value to the effectiveness of the justice system.

The impact on frontline services is already evident. ATSILS are losing staff and branch offices are being forced to close. This has already occurred in Queensland, with offices in Warwick, Cunnamulla, Chinchilla, Dalby and Cooktown closing down.[45] It is disappointing that these budgetary measures may also lead to the closure of many other ATSILS offices across Australia.

Also causing widespread concern is the uncertainty over the National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services (NFVPLS). This organisation has been providing much needed support to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims of family violence for 16 years.[46] With their funding already cut by $3.6 million in December 2013, it is unclear the extent to which this funding may be further reduced when NFVPLS is amalgamated into one of the five new programs of the IAS.

Given the extent of overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the criminal justice and child protection systems, it is difficult to understand the rationale behind these funding cuts. Unfortunately, it seems that the organisations that are best placed to provide these vital legal and advocacy services to our communities are the ones that are, or are likely to be, affected by these cuts.

(iii) Cuts to other crucial services and programs

In addition to concerns about the measures specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services and programs, the broader Budget measures will also have a significant impact on our communities. The effect of some of these measures could be felt disproportionately by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, given our higher rates of chronic disease, lower employment levels and general disadvantage. Such changes can only exacerbate Indigenous disadvantage and set back efforts to close the gap.

For instance, I am concerned by plans to withdraw $80 billion of federal investment from hospitals and schools over the next decade and the potential impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[47]

(iv) Health measures

Several aspects of the budgetary changes in the health sector are cause for concern, particularly the $7 Medicare co-payment and the cuts to national programs addressing chronic disease.[48]

The proposed $7 co-payment for visiting a bulk-billing general practitioner (GP), pathology and diagnostic services, and medication covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is a significant measure in the Budget.

The major concern is that the compounded effect of co-payments will mean a rise in out-of-pocket expenses, which will further entrench barriers to equitable access to appropriate healthcare for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

For example, a patient who visited a GP and required a blood test and X-ray would be $21 out of pocket. That sum would increase exponentially for a parent with sick children.

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) president, Associate Professor Brian Owler, has warned that the $7 co-payment, together with cuts to Indigenous health programs, may impede progress towards Closing the Gap.[49]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples already access Medicare services at a rate one-third lower than their needs require. Under the current system, 37.5% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in non-remote areas and 16.5% in remote areas find it difficult to access services because of cost.[50]

Barriers to accessing medical services need to be reduced for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The $7 co-payment presents another obstacle for our communities.

In addition, there has been a $3 million reduction to the National Tobacco Campaign and other programs aimed at reducing the risk of chronic disease.[51] This is greatly concerning, as chronic disease is the biggest cause of early death and disability in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is also a major contributor to the health equality gap.

Cutting such programs is a case of short term thinking, where, experience tells us, relatively small cost savings now will only lead to greater costs down the track. While these measures may be seen as helpful to reducing the budget deficit in the short term, they are likely to have a devastating health impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

(v) Welfare and pension age

The Budget proposal to introduce changes to youth welfare rules has also been a source of considerable anxiety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

These changes would increase the age of eligibility for Newstart and the Sickness Allowance from 22 to 24 years, and oblige first time Newstart and Youth Allowance claimants under 30 years of age to wait six months before receiving income assistance.[52]

While the stated rationale for these changes is to increase work participation incentives, they could have a devastating impact on our communities. To deny access to welfare payments for six months is not only harsh, but will fail to address the very complex issues of youth employment and disengagement from education and training, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people under 30 years.

There is also a proposal to raise the pension age to 70 years.[53] It seems grimly ironic that the average life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men is lower than the planned new pension age of 70.[54]

As I mentioned at the start of this chapter, people working in the welfare space are grappling not only with these budgetary changes, but also with the potential impact of any reforms coming out of the reviews of Indigenous training and employment and the welfare system. There does not seem to be a coherent approach to the collective impact of all of these potential reforms, which contributes to a muddled narrative.

(e) Future engagement

In general terms, the absence of clarity about how the proposed budget measures will be implemented, and the consequent impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, services and organisations, is a matter of considerable concern.

While the targeting of inefficient programs is to be welcomed, the cuts and the radical overhaul of both Indigenous specific and mainstream programs and services were planned with little or no input from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their leaders or their respective organisations.

As I said, following the Budget announcements:

The Aboriginal leadership is now mature enough to understand if cuts are needed, we're willing to put our shoulder in, but there needs to be proper engagement with our mob.[55]

This means respectful engagement with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, particularly with the sector leadership, including in the areas of criminal justice, employment, education, early childhood and economic development.

Such engagement has been conspicuous by its absence before and after the announcement of the Budget. This should be rectified as a matter of urgency.

1.4 Leadership, representation and engagement

Without Aboriginal involvement, you will fail. It’s their story; it can’t just be imposed on them... If you don’t have a respectful relationship, any talk of consultation is a fiction. If you don’t have adequate time, any talk of consultation is a fiction. You are simply the latest missionary telling them what to do.[56]

- Fred Chaney, Chair of Desert Knowledge Australia, 20 May 2014.

When I was appointed to this role, I made it clear that one of my priorities was for stronger and deeper relationships to be built between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community, with all levels of government and also among ourselves. These are relationships that need to be founded on partnership, honesty, mutual trust and respect.

For there to be effective and meaningful relationships, there needs to be a willingness of governments to involve us as active participants in the decisions that so profoundly affect us.

We need relationships that operate at multiple levels. We need relationships that are advisory and feed into the formation of policies, programs and legislation. We need relationships that are strategic, across sectors, and focus on effective implementation, so that desired outcomes are realised.

Finally, we need community driven relationships. The community level is where the political process begins, and where the operation of policies, programs and legislation are most sharply felt and experienced.

I will now discuss three current structures of engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

(a) Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council

On 10 August 2013, the Opposition Leader pledged that, if elected, he would appoint an Indigenous Advisory Council (IAC), to be chaired by Mr Warren Mundine, Chairman of the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation and Executive Chairman of the Australian Indigenous Chamber of Commerce. Prime Minister Abbott said:

I want a new engagement with Aboriginal people to be one of the hallmarks of an incoming Coalition government... If lasting change is to be achieved in this area, it has to be broadly bi-partisan and embraced by Aboriginal people rather than simply imposed by government... In this area, the problem is not so much under-investment as under-engagement.[57]

On 25 September 2013, Prime Minister Abbott announced the establishment of the IAC and confirmed Mr Mundine’s appointment as Chair.[58]

On 4 December 2013, the terms of reference were released which require the IAC to advise the government, focusing ‘on practical changes to improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’.[59] The IAC held its first meeting on 5 December 2013.

The IAC reports directly to the Prime Minister. The Chair also has monthly meetings with the Prime Minister, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs and the Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister on Indigenous Affairs.

Mr Mundine signaled an overhaul of Indigenous policy which, he said would be as bold as the economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s and would transform the welfare system for all Australians.[60] Mr Mundine said he would judge the success of the Prime Minister's Indigenous agenda based on school attendance rates, the number of people gaining university degrees and trade qualifications, and the delivery of economic outcomes, including the building of small businesses on country.[61]

(b) National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples

In 2008, then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Dr Tom Calma, convened a Steering Committee to research a preferred model for a new national representative body. A series of consultations and workshops held across Australia during 2009 culminated in the incorporation in April 2010 of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples (Congress).

The current Co-Chairs are Ms Kirstie Parker and Mr Les Malezer. As of September 2014, Congress had approximately 8200 individual members and 180 member organisations.[62]

In the reporting period, Congress coordinated a series of community dialogues with the Commission generating debate on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (the Declaration)[63] (discussed in Chapter 6) and the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples (discussed later in this chapter).

Congress was given initial funding of $29.2 million over four years, and was allocated another $15 million in the 2013-14 Budget. However, on 19 December 2013, Senator Scullion announced that the new government was ‘unlikely’ to deliver on that commitment.[64] The allocation had not been an election commitment, and the Australian Government’s position was that it did not align with the Coalition’s prioritising frontline services.[65] He also noted that Congress’ membership constituted little over 1% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, and that only 800 or so members had voted in its board elections in July 2013.[66]

After the 2014 Budget confirmed the withdrawal of the $15 million, Congress vowed to continue as ‘a strong, fearless national representative body’.[67] As of December 2013, Congress had reserves of $8.3 million, which it said would enable its continued operation for another two years.[68] Meanwhile, at its annual general meeting in February 2014, Congress announced plans to launch a public fund, expand its membership and build new partnerships, in an effort to create a sustainable financial base.[69] Ahead of the Budget, Congress reduced its staff by two-thirds. Ms Parker said that while the defunding ‘can be seen as a blow to our self-determination, it is by no means a knockout punch’.[70]

(c) Empowered Communities

In the Social Justice and Native Title Report 2013,[71] I noted that I would be watching the Empowered Communities project, led by Mr Noel Pearson, with interest.

The project aims to design a new governance model for the regions to ensure more customised and coordinated government initiatives and to provide greater empowerment of local Indigenous leaders over the activities in their communities.[72]

The group met for the first time in February 2014 and is currently formalising the proposal for their work.[73]

Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister on Indigenous Affairs, Alan Tudge, said that Empowered Communities would build on the rationalisation of programs within PM&C, and would address the problem of small communities served by multiple agencies and programs which often were not aligned with their needs.[74]

I will continue to observe the progress of Empowered Communities.

(d) Commentary

The Coalition government came into office promising a new era of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement. It really worries me to say that, even at this early stage, we are yet to see the outcomes expected of an effective, meaningful and considered engagement strategy.

That a radical reshaping of the Indigenous policy space could be planned and executed with little or no involvement by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders, communities and organisations at almost any level is disappointing.

I understand that the Prime Minister is entitled to appoint his own advisers and a diversity of views and voices is always a good thing.

Despite claims that the IAC was never intended to replace Congress,[75] the Coalition government created the IAC and removed the forward allocation of $15 million from Congress within a few months of coming to power.

Further, the Prime Minister has met monthly with the IAC Chair, as stipulated in the terms of reference, during this reporting period. In contrast, Congress has reported that the Prime Minister has not met with the Co-Chairs of Congress at all since the election.[76]

There is little doubt that the IAC members bring an impressive array of talent and experience to Indigenous issues. However, the different roles played by the IAC, as a strategic advisor, and Congress, as a representative voice, should be clarified and understood. While it is true to say that Congress’ membership has not grown as fast as was perhaps hoped, these are still very early days.

It is early days, too, for the IAC, and I trust that they will engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and advocacy bodies, as set out in their terms of reference. However, I have seen little engagement to date.

I also see the Empowered Communities concept of building relationships between government and particular regions as an opportunity to guide the development of processes so that ‘government investment is informed by local leaders and targeted to make a genuine and practical difference.’[77]

The building of these regional relationships is a step toward operationalising the model of Indigenous governance mentioned in the Social Justice Report 2012.[78] Empowered Communities covers what I have referred to as the ‘governance of government’ element.

In Chapter 5 of this report, I highlight the efforts over the last several years of our people organising themselves around their nations as a form of governance. In that chapter I discuss the benefits of building structures based on the cultural authority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations. The work underway already shows the immense potential and benefits of this localised leadership and representation.

1.5 Constitutional recognition

Starting next year, I will work to recognise Indigenous people in the Constitution, something that should have been done a century ago, that would complete our Constitution rather than change it.[79]

- Then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott, in the lead up to the 2013 election

There has been significant discussion during the reporting period about the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution. Prime Minister Abbott has identified this issue as a key priority for this term of Parliament.

Recognition has also been a focal point of my advocacy and has featured in each of my Social Justice Reports. Despite strong multi-party support, there is uncertainty surrounding the model and timeframe for such a referendum.

(a) Background

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples in the Australian Constitution has been on the agenda since 1999 when Prime Minister Howard included it in the ‘republic’ referendum.[80]

Since then we have seen commitments from all major parties for constitutional recognition in the 2007,[81] 2010[82] and the 2013 federal election campaigns.[83]

These commitments have generally revolved around reforming the Constitution to:

- recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- remove the race elements

- honour Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages

prevent discrimination on the basis of race, nationality, colour or ethnic origin.

(b) Processes, bodies and recommendations

Despite the broad political support I have mentioned above, concerted efforts towards constitutional recognition gained momentum after the 2010 appointment of the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians (Expert Panel), of which I am a member. Since that time, there have been a number of processes and bodies enacted to progress the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution.

In particular, we have seen:

- The Expert Panel’s report to government in early 2012.[84]

- A Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples convened in June 2012.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Act (Cth) passed unanimously in February 2013.[85]

- The Joint Select Committee lapsed with the calling of the federal election in September 2013 and was reconvened later that year.

- The appointment of a Review Panel in March 2014, as required by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Act (Review Panel).[86]

- The Joint Select Committee providing an Interim Report in June 2014.[87]

- The Review Panel reporting in September 2014.[88]

It is clear that between the Expert Panel, the Joint Select Committee and the Review Panel, there have been numerous consultations.

In 2012, the previous government committed $10 million to establish Recognise, a national campaign body, to raise awareness of and support for constitutional recognition. To date, more than 222 000 Australians have signed up to the campaign.[89]

Since May 2013, Recognise has been taking the campaign around Australia, on a ‘Journey of Recognition’. This journey has covered more than 25 000 kilometres by foot, bike, four wheel drive, kayak and paddleboard across the Northern Territory, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and now Queensland. The journey has involved over 162 communities and more than 14 000 Australians at 197 events.[90]

Despite all of the commitments, consultations, expert opinions, polling and campaigning, we are no closer to a referendum than we were when I was appointed to the Expert Panel in December 2010. It is for this reason that the Review Panel reported that ‘political leadership is needed to break through the ongoing cycle of deliberations.’[91]

(c) Timing of referendum

Prime Minister Abbott pledged that within a year of taking government, the Coalition would put forward a draft amendment of the Constitution for public consultation.

In December 2013, the government said the wording would be finalised by the end of 2014.[92] This timing was reiterated by Senator Scullion in March 2014.[93]

There have been suggestions around potential timeframes for holding the referendum in the life of the 43rd and 44th Parliaments, or at the 2013 or 2016 election.

However, at the time the Social Justice and Native Title Report 2014 was being completed, there was a flurry of debate about the right timing for a referendum. In its final report, tabled on 19 September 2014, the Review Panel recommended that the referendum be held no later than the first half of 2017, coinciding with the anniversary of the 1967 referendum, but earlier if the necessary conditions are in place.

Two days before the Review Panel tabled its report, the Joint Select Committee issued a statement saying that, based on the feedback it had received at community hearings, it was of the ‘strong view’ that the referendum should be held no later than the 2016 federal election. The Committee Chair, Mr Ken Wyatt, said:

The committee has gathered evidence of public willingness for constitutional change. Australians want to see the question they will be asked to vote on. Once properly informed, they will be ready to vote. In the view of the committee, what is needed is a committed public education campaign towards a specified referendum date no later than the federal election in 2016.[94]

(d) Support for constitutional recognition

There has been strong public support for constitutional recognition since the multi-party political commitments were made in 2010.

There have been various polls conducted since this time, with statistics showing:

- 61% support for the proposition from voters across the political spectrum in 2014.[95]

- 70% support for constitutional recognition according to a Vote Compass survey of 1.3 million respondents in 2013.[96]

- 80% levels of support from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in 2013.[97]

Whilst these figures are encouraging, as at September 2014, the Review Panel reported that both public support for and awareness of the importance of constitutional recognition were not yet sufficiently high.[98] In particular, recent data indicates a slight drop in awareness from 42% in 2013, to 34% in 2014.[99]

Given what I have outlined above regarding support for and public awareness of constitutional recognition, it is important that the government provides clarity around the timeframe and model as a matter of urgency.

We risk squandering all the goodwill, as well as the momentum, by delaying a vote for too long.

(e) Seizing the moment

The Review Panel called for a ‘circuit-breaker’ by releasing a finalised model of the referendum question. It also urged the government to deliver on its commitment to form a special committee of trusted national figures, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to advise and guide the referendum process.[100]

I am concerned that both support and awareness levels will have waned if the referendum to formalise the recognition does not happen until 2017.

We need to remember the spirit and enthusiasm that we had when we started the quest to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of this country.

We need to remember that this is not a radical rewriting of the Constitution, but the rectifying of a century-old omission and a change that will complete the jigsaw of our nationhood and our national identity.

This will be something in which the entire nation can celebrate and rejoice. We need to act as soon as all of the right conditions are in place, not in three years’ time.

I believe the Australian people are ready to walk with us on this next important stage of our national journey towards reconciliation. Prime Minister Abbott has demonstrated his commitment to achieving the recognition of our peoples in the Constitution. Now is the time to commit to a solid timetable for the referendum to make this happen.

1.6 Indigenous Jobs and Training Review

A number of reviews and inquiries have taken place during the reporting period that have the potential to impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

One that I have already mentioned is the review into employment and training for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by Mr Andrew Forrest. However, given the release of the 256 page report falls outside my reporting period, I will confine myself to some fairly brief observations and a summary of its recommendations.

(a) Overview

On 7 October 2013, Mr Forrest was commissioned by the Australian Government to review Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander training and employment services.[101] The findings were set out in the Creating Parity – the Forrest Review report (the Forrest Review)[102] which was delivered in early August 2014.

The purpose of the Forrest Review was to:

[P]rovide recommendations to the Prime Minister to ensure Indigenous employment and training services are properly targeted to connect unemployed Indigenous people with real and sustainable jobs, especially those that have been pledged to Indigenous people by Australian business.

...consider ways that training and employment services can better link to the commitment of employers to provide further sustainable employment opportunities for Indigenous people and finally end the cycle of entrenched Indigenous disadvantage.[103]

The Forrest Review calls for a comprehensive approach to closing the employment gap, which, it argues, disappears once Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are educated to the same level as non-Indigenous Australians.[104] The Forrest Review makes 27 recommendations, ranging across early childhood, school attendance, health, housing, criminal justice, welfare and tax incentives.

The key recommendations include:

- Making the family tax benefit payment conditional on children attending school at least 80% of the time, rising to 90%; imposing financial penalties on parents whose children fall below those targets; and tying federal school funding to the states and territories to attendance rates.[105]

- Introducing a Healthy Welfare Card, in conjunction with financial institutions and retailers, to quarantine all welfare payments other than the age and veterans’ pension, for Indigenous and non-Indigenous recipients. No cash could be raised on the card, which blocks the purchase of alcohol, tobacco, gambling and illicit services.[106]

- Reducing the number of working age welfare payments; requiring under-19s to be in work, school or training in order to receive the Youth Allowance; and supporting young people to stay on at school or move into work.[107]

- Introducing comprehensive case management for vulnerable children up to the age of three, to allow for early detection of developmental delays.[108]

- Co-locating health, nutrition and other support services for parents of small children in schools or nearby community hubs.[109]

- Conferring tax free status on new Indigenous-run businesses that create real jobs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[110]

- Requiring the federal government to spend 4% of its $39 billion purchasing budget with Indigenous-run businesses, and obliging state and territory governments to follow suit.[111]

- Requiring the federal government to negotiate contracts with the top 200 companies to increase Indigenous employment rates to 4% over the next four years; and obliging governments to recruit more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for public sector jobs.[112]

- Abolishing the Commonwealth’s Job Services Australia and replacing it with a model based on Vocational Training and Employment Centres; requiring training to be linked to guaranteed jobs, and rewarding employment service providers who place a client in a job where they remain for 26 weeks.[113]

The Forrest Review states ‘seismic, not incremental, change’ is required to ‘break the cycle of disparity’.[114] It also urges that all recommendations need to be adopted in their entirety, describing them as ‘a package of complementary measures that are linked and reliant on each other’.[115]

(b) Response

There have been a variety of reactions to the Forrest Review across the community and political spectrum.

The Prime Minister described the Forrest Review as ‘bold, ambitious and brave’,[116] and backed the linking of family tax benefits to school attendance. However, he said that the Healthy Welfare Card was ‘running ahead of current public opinion’.[117]

The Opposition Leader Bill Shorten, welcomed parts of the report, but said the Healthy Welfare Card would ‘stigmatise everyone who receives a government payment’.[118]

The Healthy Welfare Card, easily the report’s most contentious proposal, was condemned by welfare organisations, Congress and Senator Nova Peris.[119]

I stress that the introduction of the Healthy Welfare Card would require much further assessment and discussion around the effectiveness of these measures. If adopted, this would be one of the most radical welfare reforms ever proposed in Australia.

I am also concerned about how the proposals from this review might be reconciled with the outcomes of the commissioned review of Australia’s welfare system in December 2013.[120] An independent Reference Group, chaired by Mr Patrick McClure AO, was established to conduct the review. The Interim Report of this group (the McClure Review) proposed four pillars of reform:

- simpler and sustainable income support system

- strengthening individual and family capability

- engaging with employers

- building community capacity.[121]

However, I welcome the Forrest Review’s focus on health, early childhood education and real jobs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

1.7 Closing the Gap

It is not credible to suggest that one of the wealthiest nations in the world cannot solve a health crisis affecting less than three per cent of its citizens.[122]

- Dr Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 2005

(a) Background

Health inequality is a stark reminder of the great divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. As fellow co-Chair of the Close the Gap Campaign Ms Kirstie Parker and I agreed earlier this year, ‘it is a scar of our unhealed past and a stain on the nation’s reputation’.[123]

Since its launch in 2007 the Close the Gap Campaign (the Campaign) has had the goal of raising the health and life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples to that of the non-Indigenous population within a generation, to close the gap by 2030.

The Campaign is an ever growing national movement. More than 150 000 people attended almost 1 300 events on this year’s National Closing the Gap Day, while nearly 200 000 Australians have signed the Close the Gap pledge, as of late 2014. The public, it is clear, believes that we can and should be the generation to finally close the gap.

I use the phrase ‘national effort to close the gap’ to indicate both the popular movement (such as the Campaign) and successive Australian Governments’ efforts to achieve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health equality by 2030.

(b) Prime Minister’s report

Since 2009, it has become part of the national effort for the Prime Minister to report annually to Parliament on progress in Closing the Gap. As further recognition of the national importance of this effort, the report is delivered during the first sitting week of Parliament each year. Reflecting the long term nature of the challenge, this is a non-partisan occasion which is supported by all sides of Parliament and generates considerable national attention.[124]

On 12 February 2014, Prime Minister Abbott presented his first Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2014 to the House of Representatives.

The report documented progress since the national effort to close the gap began in 2008. It found that while some targets were on course to be met, there had been little or no progress on others.

The key findings were:

- Progress towards closing the life expectancy gap has been minimal.

- Child mortality rates in Indigenous children under five have declined steeply.

- The proportion of Indigenous children enrolled in pre-school programs in remote areas appears to have fallen.

- Little headway has been made in improving reading, writing and numeracy.

- The target in relation to young people acquiring a Year 12 or equivalent qualification is on track to be met.

- The employment gap has widened.[125]

The Prime Minister used his report to announce a new target regarding school attendance. Prime Minister Abbott said:

[T]he new target would be ‘all but’ met when all schools, regardless of their proportion of Indigenous students, achieved 90 per cent or higher attendance.[126]

Of course, while getting children into school is fundamental, attendance in itself does not guarantee a good education. With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in many parts of Australia now less literate than their parents and grandparents, it is vital that educational resources and quality teaching are properly funded. As highlighted in the Productivity Commission’s 2012 report on Schools Workforce, the recruitment and retention of suitably qualified teachers is a major problem for schools with predominantly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.[127]

Opposition Leader Bill Shorten supported the new school attendance target. He also emphasised the non-partisan nature of efforts to close the gap.[128]

Labor’s spokesman for Indigenous Affairs, Mr Shayne Neumann, called for new targets to reduce Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration rates, increase Indigenous access to disability services and the National Disability Insurance Scheme, and improve Indigenous participation in higher education.[129] I report more fully on the Justice Targets in Chapter 4.

(c) Progress and Priorities Report 2014

The Campaign Steering Committee publishes an annual complementary ‘shadow report’ released to coincide with the Prime Minister’s report.[130] The Campaign’s report found that Indigenous smoking rates declined from 51% in 2002, to 45% in 2008, to 41% in 2012-13.[131] In addition, it argued that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal and child health are slowly improving. These two outcomes can be expected, over time, to be important building blocks toward an increase in life expectancy.[132]

These ‘green shoots’ are evidence that the national effort to close the gap is working, and that generational change is possible.[133]

They also demonstrate the impact of ‘closing the gap’ related investment in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS).[134] That investment has built a substantial foundation which will help underpin the national effort to close the gap over the next 16 years.[135]

The Campaign argues that while progress in closing the life expectancy gap has been slow, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths since 2008 are likely to have resulted from pre-existing chronic conditions. With continued commitment and as new services, health checks and preventive health campaigns begin to take effect, the gap is likely to narrow.[136]

(d) Latest data on progress in Closing the Gap

On 30 April 2014, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Reform Council published its final report.[137] This report found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child mortality rates were continuing to fall and the literacy gap was narrowing, but unemployment was still on the rise.[138]

The report found that reading scores had improved across all year levels, while the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students achieving a Year 12 or equivalent qualification had risen, along with the number acquiring post-school qualifications.[139]

However, these gains were unfortunately not translating into employment outcomes, which had failed to improve in any state or territory since 2008. In schooling, falls in attendance were larger and more widespread than improvements, and high school numeracy levels had worsened.[140]

The report highlighted obesity as a matter for concern. More than 41% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are obese, compared with 27% of the non-Indigenous population.[141]

Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases were responsible for 33.8% of Indigenous deaths between 2007 and 2011. Although the Indigenous smoking rate fell by 3.6% during that period, it is still more than double that of non-Indigenous Australians.[142]

The independent COAG Reform Council, which was abolished on 30 June 2014, played an important role in monitoring and reporting on efforts to close the gap. I encourage the federal government to ensure that regular, independent monitoring of national, state and territory progress towards Closing the Gap is maintained.

(e) Next steps

The Campaign’s Steering Committee report argued that three things are critical to achieving these targets:

- Completing the implementation of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2012-13 (Health Plan), in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Launched in July 2013, the Health Plan marked the fulfilment of a major commitment by all signatories to the ‘Statement of Intent’. As a framework document, it emphasises a whole-of-life approach while focusing on a number of priority areas.[143]

On 24 June 2014, Coalition MP Fiona Nash, Assistant Minister for Health, announced that the government was beginning work on an implementation plan.[144] I understand that this process, being undertaken in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership in the sector, is progressing well.

- Continuing to build partnerships with Indigenous communities for the planning and delivery of health services, ideally through ACCHS. Such partnerships enable individuals, families and communities to exercise responsibility for their health, as well as helping to ensure that resources are directed to those areas of health where they are most needed, and to services and programs with the maximum impact.[145]

- Long term funding to guarantee effective implementation of the Health Plan.[146] As the 2010 Strategic Review of Indigenous Expenditure noted:

The deep-seated and complex nature of Indigenous disadvantage calls for policies and programs which are patient and supportive of enduring change... A long-term investment approach is needed, accompanied by a sustained process of continuous engagement.[147]

As Co-Chair of the Campaign, I hope that the Australian Government acts on these recommendations.

As these reports point out, we are dealing with entrenched problems with long histories. Fixing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disadvantage is a national effort requiring long term commitment and policy continuity.

We need to build on encouraging data such as the decrease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking rates, redoubling efforts and ensuring that Closing the Gap remains a national priority.

1.8 Stolen Generations

In last year’s report, I considered progress made towards achieving justice for families affected by Stolen Generations policies.

I noted how the national apology was a significant act of acknowledgement of the Stolen Generations policies and a step closer to reconciliation. I also mentioned the establishment of the Indigenous Child Placement Principles, community education campaigns, measures of restitution such as Link Up services, the establishment of the Healing Foundation and the Tasmanian compensation scheme to members of the Stolen Generations and their families.[148]

I commented that Trevorrow v South Australia[149] remains the only successful Stolen Generation litigation and that a system of ex gratia payments would provide a faster, more appropriate, less traumatising alternative to litigation for remedying these past injustices.[150]

Sadly, these sentiments are only reinforced by the 2013 decision of the Supreme Court of Western Australia, Collard v Western Australia.[151] This was the Collard family’s claim for reparations after nine of their children were removed from them by the government in the late 1950s and early 1960s. One of their children was fostered out when she was only six months old and had been hospitalised, without the consent or knowledge of her parents. A few years later, eight of the Collard children were taken from the care of their parents and placed in the Sister Kate’s Children’s Home.

In a complex and legally technical case, the Collards alleged breaches of equitable fiduciary duties against the Western Australian government for removing the children and for failing to act in their best interests with respect to their custody, maintenance and education.[152] They argued that the government had a continuing fiduciary obligation to advise and provide the plaintiffs with independent legal advice.[153] The Collards also argued that a broader fiduciary relationship, and associated duties, existed between the Indigenous peoples of Western Australia and the government as a consequence of colonisation.[154]

The court found against the Collards on all substantive arguments.[155] Further, the court found that there was a limitations issue because the Collards had not complied with the requirements of the Crown Suits Act 1947 (WA).[156]

Without going into the specifics of the decision, I am disappointed with this outcome for the Collards. The court’s finding denies that a policy of assimilation was in effect at the time the children were taken, and instead depicts the government’s actions as seeking only to protect the children from neglectful parents.[157]

The judgment also contains findings that relate to the sexual abuse of two Collard sisters. The court found that because the girls did not tell anyone about the abuse, Sister Kate’s Children’s Home had no actual or constructive knowledge of the harm done to them, and therefore did not breach any fiduciary obligations if they existed.[158] This raises concerns about whether courts are appropriate mechanisms for holding institutions and governments accountable for the abuse of Stolen children in their care.

It has long been recognised that there are significant barriers facing Stolen Generation claimants in litigation.[159] The Collard case is another example of how difficult it is to achieve justice through the courts for Stolen Generation families. Cases like this impact on reconciliation and question the extent to which court decisions are capable of recognising the true experience of families affected by Stolen Generations policies.

The Royal Commission on Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has the potential to address these issues.[160] However, caution is necessary to avoid further trauma to those who have already provided evidence at other inquiries, such as the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.[161]

I reiterate my call for the Australian Government to address the issue of reparations for Stolen Generations and their families: including acknowledgement and apology, guarantees against repetition, measures of restitution and measures of rehabilitation, in addition to monetary compensation.[162] If healing is to occur, it is necessary for government to address the physical and psychological experiences of the Stolen Generations in a way that recognises and validates trauma.[163]

I urge the Australian Government to prioritise effective reparations for the Stolen Generations and their families before the opportunity to effect personal reparation is lost to history.

1.9 International developments

There have been a number of developments at the international level during the reporting period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. Some of these developments have included specific engagement by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, while others have addressed issues that affect the lives of our peoples. These include:

- ongoing preparations for the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples 2014 (WCIP) (held on 22-23 September 2014)[164]

- the sixth session of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) (8-12 July 2013)

- the 13th session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) (12-23 May 2014).

The following is an update on the engagement by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at some of these international fora, and on the attendance and contribution to these made by my office, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner.

(a) World Conference on Indigenous Peoples

On 21 December 2010, the United Nations General Assembly agreed to organise a High-Level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly, to be known as the WCIP, in order to:

- share perspectives and best practices on the realisation of the rights of Indigenous peoples

- pursue the objectives of the Declaration.

The President of the United Nations General Assembly was invited to conduct open-ended consultations with Member States and with representatives of Indigenous peoples in the framework of the UNPFII, the EMRIP and the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples. These consultations aimed to determine the modalities for the WCIP, including Indigenous peoples’ participation.[165]

The outcome sought from the WCIP was to be a concise, action oriented document that would:

- be based on a draft text developed in consultations with Member States and Indigenous peoples (taking into account views from the preparatory processes and interactive hearings)

- contribute to the realisation of the rights of Indigenous peoples

- pursue the objectives of the Declaration

- promote the achievement of all internationally agreed development goals

- set the future direction for Indigenous peoples’ involvement in the United Nations.

Last year I reported that Congress and the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC) co-hosted the Preparatory Meeting for Pacific Indigenous Peoples in Redfern from 19-21 March 2013.[166]

In June 2013, the Sami Parliament of Norway hosted the Global Indigenous Preparatory Conference on the WCIP in Alta, Norway. That meeting produced the Alta Outcome Document, the foundation from which Indigenous representatives would negotiate the WCIP Outcome Document.[167]

In April 2012, Mr Luis Alfonso de Alba, the Permanent Representative of Mexico, and Mr John Henriksen, International Representative of the Sami Parliament of Norway, conducted inclusive consultations with Member States and representatives of Indigenous peoples on issues concerning the organisation and modalities of the WCIP. They did so as official representatives of the President of the United Nations General Assembly (PGA).

It was generally acknowledged that two representatives would eventually become the Co-Chairs of the WCIP, and with this in mind, the June 2013 Alta meeting endorsed Mr John Henriksen to represent Indigenous peoples.

However, at the beginning of 2014 several Member States disagreed with this proposed structure as it was seen to be giving preference to the participation of Indigenous peoples to a level equal to Member States of the United Nations.

In any event, it was negotiated that the PGA would appoint two Indigenous Advisors. These were Dr Myrna Cunningham, an Indigenous rights activist from Nicaragua and former President of the UNPFII, and Mr Les Malezer, Co-Chair of Congress.

Interactive meetings facilitated by the PGA were held in the lead up and as preparation for the WCIP.

A ‘Zero Draft Outcome Document’ (Zero Draft) was released in July 2014.[168] Domestic consultations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives and the Australian Government were conducted on the Zero Draft in August. Versions 2 and 3 Draft Outcome Documents were released in late August and early September respectively, with the Final Draft Outcome Document released on 15 September, a week before the WCIP.

An update on the outcomes of WCIP will be in next year’s Social Justice and Native Title Report.

I am pleased to report that the domestic consultations, facilitated by the PM&C, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Congress, were conducted respectfully, cooperatively and in good faith where all opinions were valued.

This resulted in the Australian Government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives working together to develop an agreed position for the WCIP that was not only acceptable to both, but also capable of being advocated to United Nations Member States and Indigenous peoples alike.

This spirit was replicated at the international interactive meetings, where I am pleased to say that Australia took a leading role and was considered to be a ‘friendly’ nation, that is, one that generally supported the position of Indigenous peoples.

(b) Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The sixth session of EMRIP was held in Geneva in July 2013. As one of the two Indigenous specific forums of the United Nations, the EMRIP has a standing agenda item on the Declaration.

The Indigenous Peoples Organisation (IPO) Network submitted statements on the following agenda items:

- WCIP

- access to justice

- the Declaration.

I attended EMRIP and endorsed the statements by the IPO Network on the WCIP and the Study on Access to Justice. These statements by the IPO Network stressed the importance of Indigenous participation at the WCIP, including all preparatory meetings and urged the United Nations Human Rights Council to endorse the Zero Draft from the WCIP preparatory meeting in Alta. They also requested an extension of the Study on Access to Justice in the promotion and protection of the rights of Indigenous peoples.[169]

(c) United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

The 13th session of the UNPFII was held in New York in May 2014. Like the EMRIP, it also has a standing agenda item on the Declaration.

The 13th session addressed recommendations on the following themes:

- principles of good governance

- implementation of the Declaration

- dialogue with the Special Rapporteur WCIP Study on an Optional Protocol to the Declaration

- Indigenous children and youth

- second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People

- post-2015 development agenda

- dialogue with UN agencies and funds

- future work and emerging issues of the UNPFII.

As Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, my office provided statements to the UNPFII, addressing:

- the centrality of effective Indigenous governance to self-determination and sustainable development[170]

- the need for States to conduct an audit of their laws and policies, conduct human rights training, and engage in meaningful dialogue with Indigenous people in order to implement the Declaration[171]

- the importance of the role of the Special Rapporteur[172]

- the importance of improving both resourcing of services and data collection regarding Indigenous youth self-harm and suicide.[173]

My office joined with the IPO Network in acknowledging and specifically thanking Professor James Anaya for his work as Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, and formally congratulated Ms Victoria Tauli-Corpuz on her appointment to the role, commencing in June 2014.

The IPO Network also submitted several interventions across those agenda items including governance[174] and Indigenous children and youth.[175]

The Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) authorised the UNPFII to conduct a study on the development of an optional protocol to the Declaration.

Ms Dalee Sambo Dorough and Ms Megan Davis, Members of the UNPFII, were appointed to undertake a study focusing on a potential voluntary mechanism to serve as a complaints body at the international level. In particular, this mechanism would deal with claims and breaches of Indigenous peoples’ rights to lands, territories and resources at the domestic level. The outcome of the study was submitted to the UNPFII’s 13th session.[176]

1.10 Australian Human Rights Commission complaints

The Commission has two roles; a policy and advocacy role, and a role to investigate and conciliate complaints made under federal human rights and discrimination law. The types of complaints received help to inform the policy and advocacy work of the Commission.

The Commission receives a wide range of complaints from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including complaints about individual acts of discrimination and complaints about systemic discrimination.

The majority of complaints made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were about racial discrimination, as can be seen from Table 1.1.

The information regarding the number and types of complaints received this year has been provided by the Commission’s Investigation and Conciliation Service, who I thank for their assistance and important work.

(a) Complaints received in 2013-14 by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Table 1.1 below provides the number and percentage of complaints by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples received in the last financial year under all relevant legislation. Table 1.2 provides the outcomes of finalised complaints during my reporting period.

Table 1.1: Number and percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander complaints received in 2013-14

|

RDA[177]

|

SDA[178]

|

DDA[179]

|

ADA[180]

|

AHRCA[181]

|

Total

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aboriginal

|

159

|

36%

|

5

|

1%

|

17

|

2%

|

1

|

0.5%

|

5

|

2%

|

187

|

9%

|

|

Torres Strait Islander

|

1

|

-

|

0

|

-

|

0

|

-

|

0

|

0

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

|

Both of the above

|

3

|

1%

|

1

|

-

|

0

|

-

|

1

|

0.5%

|

-

|

-

|

5

|

-

|

|

None of the above/

Unknown

|

278

|

63%

|

438

|

99%

|

738

|

98%

|

170

|

99%

|

259

|

98%

|

1883

|

91%

|

Table 1.2: Outcome of complaints from ATSI peoples finalised in 2013-14

|

Outcome

|

Number of complaints from ATSI peoples

|

Percentage of complaints from ATSI peoples

|

Comparison with percentage of all finalised complaints

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Conciliated

|

110

|

62%

|

49%

|

|

Terminated/declined

|

31

|

17%

|

23%

|

|

Withdrawn