Capturing the diversity advantage - Our experiences in elevating the representation of women in leadership - A letter from business leaders (2011)

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Our

experiences in elevating the representation of women in leadership

A letter from business leaders

Capturing the diversity advantage

For

most Australian companies, the transition from Phase 1—Getting in the

game, to Phase 2—Getting serious, will be most relevant. However, a number

of our companies have been in Phase 2 for some time. Some of us see a path to

continued improvement, with a payoff that will go further than just gender

balance. Woolworths and CBA’s experiences, starting on page 30, show how

individual companies have navigated Phases 1 and 2, and how they are beginning

to think about the next phase of their journey.

Our

collective experience tells us that after steady wins, many of us reach a

plateau. Most of us have weak spots in our organisations where we’ve still

made little progress.

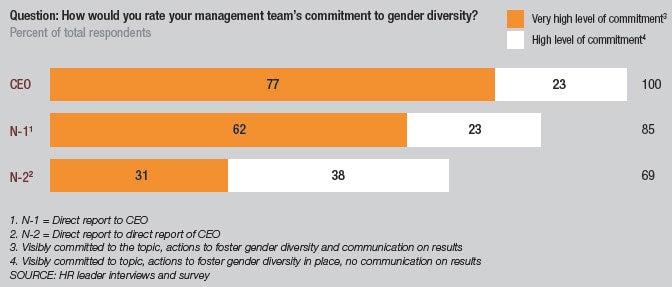

Why do we

reach this plateau? We believe it is because deeply embedded cultural factors

get in the way. Many of us speak of members of our own management teams who

don’t share our confidence in the vision. Exhibit 15 suggests that our

efforts haven’t yet fully translated into initiative-taking in the broader

organisation. As such, the shift from Phase 2 to Phase 3 is about tackling the

underlying cultural barriers that work against the goal of greater

representation of women in leadership.

While some

organisations and their leaders will struggle with the business imperative to

shift beyond Phase 2, most of us hope for real gains beyond the plateau. Part of

the challenge of describing this phase of the journey is that few of our

companies would claim to have achieved the aspiration of a culture that fully

supports gender balance.

Given

this, we can take encouragement from other cultural transitions we have made in

areas such as customer service, collaborative leadership and safety. This

requires an integrated change program.

Taking a

safety analogy, we know that safety cultures take decades to build. However,

leaders do not negotiate safety objectives. In safety cultures, safety metrics

receive focus akin to financial ones. Data is shared openly with an expectation

of accountability. In a safety culture, the CEO is a role model. The CEO

complies with on site policy, even when in the CBD head office. Before

descending every staircase, force of habit sees them conclude their phone call,

and return the handset to their pocket.

In safety

cultures, there is a belief that every injury is preventable and accidents are

not met with an attempt to excuse. Every person in the organisation, from newest

to most experienced, is responsible for safety. Safety cultures are blindingly

obvious to new joiners—a three-day safety induction builds capability and

sets the tone. Safety ‘shares’, where recent incidents are

highlighted, provide regular reminders and reinforce accountability. In a safety

culture, people with poor records are not promoted—a contractor who

jaywalks outside the head office is not invited back.

Consider

what our organisations would look like if gender balance was ingrained in our

culture the way safety is. We wouldn’t shy away from a ‘zero

defect’ type of goal. We would not tolerate behaviours that were careless

or inconsistent with a culture of gender balance. No leader would be promoted if

they had a poor record on diversity. We would be open about failure—we

would conduct challenging reviews of our mistakes to ensure we didn’t

repeat them. We would operate with more flexibility.

We also

don’t believe that the imperative for cultural change will be solely

elevating the representation of women in leadership in itself. It is more likely

to be part of a broader transformational change. Says Ralph Norris of CBA, ‘What really matters is changing underlying mindsets and behaviours.

We’ve come a long way in our journey towards a customer service culture. I

believe that diversity is a big part of the next stage in our cultural

journey.’

This shift

in culture requires engaging a much broader cross section of the organisation.

In Phase 2, the centre of gravity shifted from HR to senior leadership. Now the

whole system is engaged—from top to middle to front line.

To unlock

the benefit of gender balance as part of a broader change, there are a number of

actions to focus on:

1.

Develop inclusive leaders who harness

talent. Telstra

believes that building leadership capability is at the foundation of its culture

and future success. Says David Thodey of Telstra, ‘in

my mind, gender (diversity) and inclusiveness is a broader leadership issue.

Great leaders know how to get the best out of their people regardless of their

gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation.’

We know

that the highest performing leaders are inspiring. They bring out the best in

others. They motivate others by creating common purpose and building on

individual strengths. They foster collaborative leadership and decision making.

They engage others and they turn difficult situations into learning moments.

They also create the energy to sustain change.

As a

result, these leaders do things differently. They develop others and build

accountability through coaching and feedback. Most importantly, gender does not

get in the way. They also build high performing teams to execute faster and get

better results.

Giam

Swiegers at Deloitte

says, ‘I’m most proud that our efforts to build a team that values gender

diversity are paying off. It’s common now for our Practice Leads to

proudly share stories and evidence of their successes in developing, sponsoring

and promoting female

talent.’

2.

Weed out entrenched

biases. We find that

corporate and individual mindsets, particularly biases, can be hard to shift.

Our experience is consistent with McKinsey & Company research in the US that

provides evidence of common biases, and how they sabotage promotions processes.

For

example, this research shows that many managers commonly overlook women for

certain jobs. One cause of this is ‘best intentions’—wanting

to prevent a woman from failing because ‘everybody knows you can’t

put a woman into that particular slot’ or ‘that slot could never be

done part time’.

Another

aspect outlined is that often women are seen as more risky choices for open

positions, and therefore managers look more to their experience than their

potential (whereas men are more confidently promoted on the basis of potential).

There is

also a sense that women must watch what they say—in a masculine world,

they can seem aggressive when men seem assertive. This can create real

self-consciousness and a sense that women are not truly accepted in their

organisations. It can also reduce perceived and actual performance. Also, men

will often give more direct and personal feedback to men than to

women—often with best intentions—but with significant lost

development opportunities.

As a first

step, many of us have introduced training or workshops that seek to surface

unconscious bias that gets in the way of merit-based appointments and

flexibility. Cameron Clyne at NAB believes it is a critical issue to

address, ‘How do we counter it, how do we change the way we select, recruit, induct

to overcome that unconscious bias within an organisation that may lead us down a

more narrow recruitment and development path.’

This year,

almost 200 senior leaders at NAB will complete their Consciously Addressing

Unconscious Bias program. The lessons learned will then be applied in everyday

decision-making processes that commonly occur in the workplace. As a part of

this program, each leader receives one-on-one coaching to support them in

recognising their own biases and addressing these on an individual

level.

Exhibit 15: Building commitment to gender diversity is

challenging

Exhibit 16: Shifting culture to build gender diversity

at Rio Tinto Alcan Bell Bay

|

Context

and Objectives

|

|

|

Actions

Taken ‘The

Basics’

‘The

Extras’

‘The

Magic’

|

Lessons

Learned

|

ANZ

recently sponsored an Australasian tour of a diversity expert that focused on

the business case for building more inclusive companies. Awareness sessions with

800 leaders, including ANZ’s top 200 executives, community groups and

clients, served to surface issues and encourage additional actions to address

mindsets that might work against women’s advancement. This approach will

be cascaded across the organisation, asking leaders to develop personal plans

for building a more inclusive business.

Telstra’s

efforts have focused on moving from a compliance-based approach to a culture

that builds inclusive leaders. This approach has involved vigorous work to

change attitudes and behaviours both internally and externally. Engaging men,

and all leaders across the organisation, has been a priority. One example of

this approach is ‘Kitchen Table’, a series of group-level

discussions, aimed at fostering conversation and shifting mindsets around

diversity and inclusion.

In advance

of a ‘Kitchen Table’ discussion, senior leaders in each Business

Unit are sent granular data about their specific groups’ diversity

objectives, performance against them, and gaps that might exist. Leaders are

engaged in an open discussion about their own group’s story and dynamics.

They are invited to come up with the reasons and biases that might be getting in

the way, together with solutions to improve.

The focus

is on shifting mindsets and individual behaviours by holding a mirror to each

part of the organisation and the role individual managers play, rather than

applying ‘one-size fits all’ programs. Action plans are then owned

by the group’s leaders, not by HR, with leaders directly accountable for

inclusive approaches in their everyday team leadership.

Rio Tinto

Bell Bay provides an example of shifting mindset and behaviours to those more

supportive of gender balance. Exhibit 16 details how Bell Bay doubled the share

of women working on site within two years. This story highlights the investment

required to shift mindsets, and the payoff for doing so.

At Bell

Bay, many workers believed that having more women on site would hurt the

site’s safety record. To address this, rosters were analysed for

correlation between gender and accidents. Others expressed concern that women

weren’t strong enough. In response, a consultant looked at physical

requirements for roles and at how women’s capabilities met these

requirements.

In these

instances, the management team worked hard to listen—without immediately

refuting staff concerns. In Rio Tinto’s fact-based culture, the key was

providing evidence that more women wouldn’t lead to more incidents or to

the job not being done properly.

Armed with

this information, and supported by diversity champions with experience of

working with women, management was able to build a culture that would support

greater diversity—with very strong results.

Rio Tinto

Bell Bay managed to reach its goal of moving the share of women from six to

almost twelve percent in the two year timeframe. Management and staff alike felt

strongly that Bell Bay was a better place to work.

So, we can

all agree that improvement requires changing underlying mindsets and behaviours

across the organisation. To do so, we must understand what exactly it is in our

culture that is standing in the way. Is it a rigid image of what success and a

career path looks like? Is it fear of working with people who are different? Is

it tradition? Is it fear of change?

3.

Take flexibility from marginal to

mainstream. Research

tells us that the two biggest barriers to women progressing in organisations are

the ‘anytime/anywhere’ business culture and the ‘double

burden’ on women who are likely to take up more family commitments outside

of work hours.

Exhibit 17: IBM flexibility example

|

Context

and Objectives Over

the last decade, IBM has worked to foster a culture where flexibility is viewed as a positive work choice with individual, team, organisation and client benefits. Flexibility is a core part of IBM’s retention and engagement strategy for both men and women. |

|

|

Actions

Taken The

focus is twofold: first, on how the world of work is evolving; and second, on IBM’s goal of building an inclusive work environment.

|

Lessons

Learned

|

Our

companies agree that a genuine commitment to flexibility is fundamental to

elevating the representation of women in leadership.

Says Gail

Kelly of The Westpac Group ‘Flexibility

needs to be mainstreamed—it’s the key to unlocking a huge part of

our talent

pool.’

While we

all have flexible work policies in place and provide options for women and men

who are balancing work and family life, it remains unusual for men to take

advantage of them, or for women to take advantage of these policies at senior

levels. This suggests that there remains a prevailing bias in our organisations,

that you cannot be successful as a senior executive on a flexible program. There

may be fear among men and women that choosing a flexible work arrangement

creates the perception that they are no longer serious—that they are

‘opting out’.

Many women

(and men) feel forced to trade off work and family. We will have fully captured

the diversity advantage when those trade-offs aren’t as stark, and perhaps

don’t have to be made at all. Says Andrew Stevens from IBM, ‘Is

it career or family? Let’s make it both.’

For more

than 10 years, IBM has worked hard to build flexibility into its culture. This

has required education for both managers and employees alike, as shown in

Exhibit 17. It has also particularly helped with the retention of women. Most of

us are a long way from having flexibility so ingrained in our cultures that

women (and men) will always see a way to stay engaged in the

workforce.

Pacific

Brands provides an early glimpse of what it might look like when

‘flexibility goes mainstream’. There is a strong belief across the

company that with today’s technology, going home for dinner often should

be possible for most, including senior leaders.

There is

also a shared understanding around how appointments are made at Pacific Brands.

As Sue Morphet says, ‘first

we find the best person for the role, based on capability, and then if we can,

we will work to adapt to suit any specific need that the person might have for

flexibility’.

Unusually,

Pacific Brands has achieved this without a formal set of programs and

initiatives—but rather through embedded cultural norms and role modelling.

While the organisation believes it has a long way to go before it captures the

full ‘diversity dividend’, it has achieved real progress.

Sue

Morphet believes that ultimate success will be characterised by organisations

structuring working models with the assumption that men and women equally carry

the responsibility of managing the household. In that state, the work and family

trade-off will be less stark. There will be enough senior roles that can

accommodate gender balance.

In this

third phase, we aspire to a cultural shift. We recognise the need for inclusive

leaders who harness talent. We counter biases—both conscious and

unconscious. We also aspire to free our employees from the trade-off between

work and family by providing a path to senior roles that allow

flexibility.

Where

mindsets are deeply entrenched, it will take years and perhaps multiple CEO

terms to sustain the journey. It takes more than the CEO and top team, the whole

organisation must engage in the cultural shift. However, by eliminating cultural

barriers, companies can move beyond the plateau. Diversity will become part of

our organisations’ DNA, and the way we operate. It will be sustainable and

will enable us to capture the leadership advantage.

***

Questions

we would encourage you to think about:

If you had

to design your organisation from a clean sheet so that you eliminated barriers

to women’s representation in leadership, what would it look

like?

Given that

most of your executives are unlikely to be deliberately sexist, what are the

more subtle or unconscious biases that get in the way of elevating the

representation of women in leadership?

Where have

you had success in achieving cultural change in your career? What did you do?

How would those actions translate to creating a culture supportive of greater

female representation?

As with

any fundamental change, the path to achieving greater gender balance is not easy

or smooth. Not all levers are likely to be at the disposal of even the largest

companies. We all know that long-term investment is required. We also know that

if we take the pressure off we risk making no progress, or worse, sliding

backwards.

Some of us

believe that fundamental policy reform at a national level is key to progress.

They point to changes in policies around childcare, immigration and tax as

essential enablers to elevating women’s representation in

leadership.

We all

believe that changes to the broader Australian culture would also help. However,

our collective experience tells is that there is much improvement to make before

these obstacles are true constraints.

We

don’t have all the answers, but we hope that by telling our stories, other

Australian companies can advance themselves along this journey, and in return

share with us their own lessons and breakthroughs.