Native Title Report 2009: Chapter 1

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Native Title Report 2009

Chapter 1: The state of land rights and native title policy in Australia in 2009

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Policy approaches to land rights and native title – the legacy of the Howard Government

- 1.3 The Rudd Government’s response – new promises, a fresh approach in 2008-09?

- 1.4 Significant cases affecting native title and land rights

- 1.5 International human rights developments

- 1.6 Significant developments at the state and territory level

- 1.7 Conclusion

1.1 Introduction

The reporting period for this Report is 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2009. Throughout this period, there was significantly more activity in native title law and policy than I witnessed in the first five years of my term as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner.

Throughout the reporting period, the Government pursued its commitment to improving the operation of the native title system. While no momentous improvements were made, many of the changes over the year will impact on the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

In this Chapter, I examine changes and other decisions affecting native title which were made throughout the reporting period. I also summarise my view on how these developments impact on the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

I begin this Chapter with a reflection on the previous Government’s approach to land rights and native title, including its 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Native Title Act); the 2006 amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) and the 2007 compulsory acquisition of lands for the purposes of the Northern Territory Emergency Response. These significant policies have lingering effects on the operation of native title and land rights regimes today, and provide the starting point for discussion on what changes are now necessary.

Next, I consider the Rudd Government’s response, including its new promises and whether a fresh approach to native title was seen in 2008-09. I look at the native title system in numbers, including the native title determinations which were made over the reporting period and the Government’s budget allocation for native title. I then consider the legislative and policy changes including the:

- Native Title Amendment Bill 2009 (Cth)

- Evidence Amendment Act 2008 (Cth)

- Federal Justice System Amendment (Efficiency Measures) Bill (No 1) 2008 (Cth)

- Australian Government’s discussion paper on optimising benefits from native title agreements.[1]

I have also identified policy areas in which the Government initiated action but where momentum now appears to be waning. These include financial assistance to the states and territories for compensation, the Joint Working Group on Indigenous Land Settlements, the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy, and regulation and funding of Prescribed Bodies Corporate (PBCs).

I then examine three significant decisions on native title and land rights. I summarise Wurridjal v Commonwealth (Wurridjal)[2] in which the High Court examined the constitutional validity of compulsory acquisition under the Northern Territory intervention. In FMG Pilbara Pty Ltd v Cox (FMG Pilbara),[3] the Federal Court gave greater guidance on what it means to negotiate in good faith under the Native Title Act. The National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) gave its first decision that a mining lease must not be granted in Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation (Jamukurnu - Yapalikunu) / Western Australia / Holocene Pty Ltd (Holocene).[4]

This Chapter also considers a number of international developments, directly relevant to Australia. In this reporting period, the Government signalled its support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples);[5] two United Nations treaty monitoring committees delivered concluding observations on Australia; a complaint against Australia was made to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination; and once again, a delegation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people attended the annual session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Finally, no examination of native title would be complete without a consideration of the policies of the states and territories. Therefore, I briefly look at significant developments at the state and territory level, particularly the development of an alternative settlement framework in Victoria.

1.2 Policy approaches to land rights and native title – the legacy of the Howard Government

John Howard served as the Australian Prime Minister for four consecutive terms over eleven years. It is misguided to consider current policies on Indigenous land rights and native title without reflecting on the lingering effects of the Howard Government’s policies and the response of the current Australian Government.

The Howard Government’s overarching policy on Indigenous affairs was to integrate Indigenous Australians into ‘mainstream society’, and ignore Indigenous peoples’ distinct political, social and cultural identity and our status as the traditional owners of the country.

This policy extended to all areas. The Howard Government was unwilling to support the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and considered that endorsing the Declaration ‘would lead to division in our country’.[6] In 2005, it dismantled the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), mainstreaming the delivery of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across all federal departments.

And yet, as my friend Peter Yu has said:

We are not white people in the making, nor are we simply another ethnic minority group. We are, at a fundamental level part of the modern Australian nation. But, within this nation, we have a very particular position. We are Australia’s Indigenous people, the first people of this land, and we continue to have – as we have always had – our own system of law, culture, land tenure, authority and leadership. It follows then, that treating us the same as everybody else will not deliver equality, but is in fact discriminatory.[7]

The Howard Government’s approach to Indigenous peoples was easily identifiable in its policies on land rights and native title. Over its 11-year term, it made changes to native title and land rights policies to ‘normalise’ Indigenous peoples’ interests in the land, and in doing so, reduced the recognition of Indigenous peoples’ human rights.

Significant changes made to native title and land rights during the Howard Government’s term included the:

- 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act

- 2006 amendments to the ALRA

- 2007 compulsory acquisition of lands for the purposes of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (the Northern Territory intervention).

The Howard Government accompanied these changes with words that misled the broader public on the law. For example, in 2006, after the Federal Court’s first instance decision in the Noongar case (which determined that some native title rights existed over Perth), the Howard Government was reported as saying that Australia’s beloved beaches were no longer ‘protected’ from native title.[8] Philip Ruddock, then the Attorney-General, stated:

It is not possible to guarantee that continued public access to all such areas in major capital cities in Australia would be protected from a claim to exclusive native title.[9]

This is clearly not an accurate reflection of the law.[10]

Despite all this, the Howard Government told the United Nations that ‘[s]uccessive Australian Governments have implemented a range of initiatives in support or recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights’.[11]

It is necessary to reflect on the impact of past policies of the past decade when considering the status of the native title system today and how it could be improved tomorrow.

(a) The 1998 Wik Amendments

The most significant changes made to native title during the Howard Government’s term was the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) (the Wik amendments), a legislative response to the High Court’s decision in Wik Peoples v Queensland (Wik).[12] In Wik, the High Court held that native title could survive on a pastoral lease if there was no clear intention to extinguish it when the lease was granted.

In the Native Title Report 1998, the Social Justice Commissioner said that the High Court of Australia had laid the foundation in Wik for the coexistence and reconciliation of shared interests in the land and that ‘[i]n many ways the decision presented Australia with a microcosm of the wider process of reconciliation’.[13]

But the opportunity for reconciliation provided by Wik was lost. The reactions sparked by the decision were intense and deeply divisive, and the consequent amendments to the Native Title Act were a devastating blow to Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Although there was discussion on amending the Native Title Act prior to the Wik decision, the earlier discussions focused on improving the ‘workability’ of the Act. However, after the Wik decision, the focus changed.

Legislative amendments became a vehicle for ‘bucketloads’ of extinguishment.[14] ‘Certainty’ for non-Indigenous land holders became the new catchcry for legislative change.[15]

The Howard Government responded with a ten-point plan,[16] and amendments were passed in 1998. The Wik amendments, which added 400 pages of law, drastically increased the complexity of the Native Title Act and changed the system markedly. The key changes included:

- Extinguishment of native title. The ‘validation and confirmation provisions’ of the amendments validated certain acts which took place on or after 1 January 1994 (the day the Native Title Act commenced) and before the 23 December 1996 (the day the High Court handed down its decision in Wik), and which may have not been valid at the time because the government had not complied with the Native Title Act. The amendments made these acts - which are called intermediate period acts - valid, and said that they were always valid. The amendments also deemed certain tenures granted before the Wik decision to have either extinguished or impaired native title. Where the interests were granted by the state governments, the amendments authorised the states to introduce complementary legislation to the same effect. Schedule 1 of the amended Native Title Act lists interests which are deemed to permanently extinguish native title. This list is 50 pages long.[17]

- Changed the right to negotiate provisions. The right to negotiate was included in the original Native Title Act in recognition of the ‘special attachment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to their land’.[18] The 1998 amendments authorised states and territories to introduce legislation that diminished the right to negotiate by introducing schemes which provide for exceptions to the right. The amendments also changed the right to negotiate in the Native Title Act itself, generally replacing it with the lesser rights to comment or be notified.

- Changed the registration test. The amendments established a higher threshold for the registration test and required that the Registrar be satisfied that certain procedures had been undertaken by the claimants, and that they had fulfilled certain merits.

- Provided for Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs). The ILUA provisions were a positive feature of the amendments, offering the foundation for parties to negotiate voluntary and binding agreements about the use of the land, the intersection of various rights and interests, and how the relationship would proceed in the future.

- Changed the functions of Native Title Representative Bodies (NTRBs). The amendments redrew the boundaries of representative body areas (reducing the number of NTRBs), reassessed the existing bodies’ eligibility, increased the Minister’s control over the bodies, removed the requirement that representative bodies be representative and increased their responsibilities and functions. Despite increasing the load on NTRBs, the changes were not accompanied by an increase in funding.

Many of these amendments were justified on the basis of pursuing formal equality.[19] Yet it is now widely accepted that the amendments seriously undermined the protection and recognition of the native title rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Nonetheless, the Howard Government considered that the Wik decision had simply accentuated the shortcomings of the original Native Title Act and that:

The 1998 amendments addressed these difficulties, and followed an open and participatory consultation process with all interested parties. The amended Act clarifies the relationship between native title and other rights and gives the States and Territories the capacity to better integrate native title into their existing regimes. The amendments also established a framework for consensual and binding agreements about future activity known as Indigenous Land Use Agreements or ILUAs.[20]

That outlook was not shared by all. In 1998, Indigenous representatives rejected both the substance of the amendments and the process by which it was arrived at. The National Indigenous Working Group prepared a statement, which was read into the parliamentary record on the day before the amendments were debated:

We, the members of the National Indigenous Working Group, reject entirely the Native Title Amendment Bill as currently presented before the Australian Parliament.

We confirm that we have not been consulted in relation to the contents of the Bill...and that we have not given consent to the Bill in any form which might be construed as sanction to its passage into Australian law.

We have endeavoured to contribute during the past two years to the public deliberations of Native Title entitlements in Australian law.

Our participation has not been given the legitimacy by the Australian Government that we expected...

We are of the opinion that the Bill will amend the Native Title Act 1993 to the effect that the Native Title Act can no longer be regarded as a fair law or a law which is of benefit to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples...

The National Indigenous Working Group is extremely disappointed that the Australian Government has failed to confront issues of discrimination in the Native Title laws and implicitly provoked the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to pursue concerns through costly and time consuming litigation, rather than through negotiation...

The National Indigenous Working Group on Native Title absolutely opposes the Native Title Amendment Bill, calls upon all parliamentarians to cast their vote against this legislation, and invites the Australian Government to open up immediate negotiations with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples for coexistence between the Indigenous Peoples and all Australians.[21]

Although the 1998 amendments severely damaged the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Government, the strength and resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has meant that we have endeavoured to make the most out of the weakened system.

This Government has not made any commitment to reviewing the impact of the 1998 amendments nor identifying where they may be wound back. Although the original Act was also not perfect, the impact of the 1998 amendments and the operation of the original Native Title Act should be used to inform current debate over what amendments are necessary to ensure the native title system operates in a just, equitable and effective way.[22]

(b) The 2006 ALRA amendments

The Australian Government is only directly responsible for land rights policy in the territories. During its term, the Howard Government’s policy toward land rights resulted in considerable changes to the Northern Territory’s land rights regime. This shift in policy has become relevant across the country as it is now being applied to state land rights regimes via partnerships and funding arrangements between the federal and state governments. I discuss this further in Chapter 4 of this Report.

The Howard Government amended the ALRA in 2006.[23] The amendments covered a number of measures, one of which sought to ‘promote individual property rights’ on Aboriginal land by enabling a Northern Territory entity (such as the Northern Territory Government or a statutory authority established by it) to be granted a 99-year lease from the traditional owners over an entire township. Long-term subleases could then be granted to Aboriginal people and others without each sublease having to be negotiated with the relevant Land Council.[24]

Again, the intention was to ‘normalise’ Indigenous communities through the mainstreaming of service delivery and the creation of market economies. Mal Brough, the Howard Government Minister for Indigenous Affairs, said ‘[w]e are talking about creating an environment for the sort of employment and business opportunities that exist in other Australian towns’.[25]

At the time, I raised a number of concerns with the policy, including that it could lead to significant loss of control of land by Indigenous peoples; create complex succession problems; create smaller and smaller blocks as the land is divided amongst each successive generation; and cause tension between communal cultural values with the rights granted under individual titles. I was also concerned about the ability of traditional owners to confront these issues and give their free, prior and informed consent to long-term and large area leases while their capacity is inhibited.[26]

Another significant concern I voiced is that the amendments allow the government to use the Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) to pay for the 99-year head leases. The fund, which was set up to provide benefits to Indigenous people in the Northern Territory above and beyond basic government services, can now be used by the government to acquire, administer leases or pay the rent. For example, rents payable to traditional owners who agree to lease their land under the ALRA will come, at Ministerial direction, not from the lessee (eg the Northern Territory Government) but from the ABA.

In August 2007, the Howard Government told the United Nations that:

Under the proposed reforms, traditional owners will be able to grant a 99 year head-lease over a township area. Granting a head lease will be entirely voluntary. Traditional owners and the Land Council will negotiate the other terms and conditions of the head-lease, including any conditions on sub-leasing. Sub-leases may be issued to individual tenants, home purchasers, and business and government service providers. The underlying inalienable title will not be affected.[27]

I do not believe this to be the case.

On 12 June 2007, the then Shadow Minister for Families, Community Services, Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation, Jenny Macklin, spoke against the amendments.[28] However, as the current Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Jenny Macklin now supports the leasing scheme and is working with the states to have it applied across the nation.

Some traditional owners have expressed their dismay at this:

When John Howard and Mal Brough lost their seats, we were happy. But now you are doing the same thing to us, piggybacking Howard and Brough’s policies, and we feel upset, betrayed and disappointed. ...

This is our land. We want the Government to give it back to us. We want the Government to stop blackmailing us. We want houses, but we will not sign any leases over our land, because we want to keep control of our country, our houses, and our property.[29]

In a statement given by a Warlpiri delegation from Yuendumu when Parliament was opened in 2009, it is clear that there are very strong feelings that leases are not necessarily being entered into on voluntary and informed grounds.

Land for Housing... We are just being blackmailed. If we don’t hand over our land we can’t get houses maintained, or any new houses built. ...

We got some land back under the NT Land Rights Act. Now they want to take the land our houses are on, so they can control us. They are talking about 60 or 80 year leases, but we know that we won’t ever get it back.

We have cultural ties to our land. Our land is not for sale. Without the land we are nothing. Our spirit is in the land where we belong. If we give up our land we are betraying our ancestors. Every bit of our land is precious. ...

Every time Government officials come to Yuendumu to ‘consult’ with us, they don’t listen to us. They just tell us what their plans are. When any of us speak up about our concerns, it’s as if they have deaf ears. They just go on with their plans as if we had said nothing. There is no communication. They treat us like kids.

We are proud Warlpiri people. It is a great insult to be treated like this.[30]

I am still concerned with various aspects of this policy, including how Indigenous people are being involved in the decision making process and what the long-term impacts on cultural, economic, political and social rights will be. I discuss these concerns in more detail in Chapter 4 of this Report.

(c) The 2007 compulsory acquisition of land for the purposes of the Northern Territory Emergency Response legislation

On 21 June 2007 the Howard Government announced the Northern Territory Emergency Response,[31] also known as the intervention. The intervention was originally a response to a report on child sexual abuse called Little Children are Sacred.[32] The current Government states that the intervention ‘has a wide range of measures designed to protect children and make communities safe’ and to ‘create a better future for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory’.[33]

The various measures which make up the intervention have significant implications for Aboriginal owned and controlled land.

The Government considered it necessary to control the land for aspects of the intervention to be done quickly.[34] Consequently, the Government compulsorily acquired five-year leases over Aboriginal owned land in the Northern Territory. It took over the control of town camps; allowed for the suspension of the permit system which ensures traditional owners can control who enters their land; and suspended the future acts regime in the Native Title Act. The Government introduced these measures with the intent that they would assist in building new houses, upgrading existing houses and bringing in new arrangements for the management of public housing in communities.[35]

In the Native Title Report 2007, I raised my concerns with these aspects of the intervention. Particularly:

- the use of compulsory acquisition and the lack of consultation or discussion with the Aboriginal land owners

- the possibility of a significant interruption to community living

- the breadth of the Minister’s discretion over what happens on the lands subject to compulsory acquisition and the lack of accountability of those decisions to Parliament

- the apparent displacement of traditional rights of use and occupation (under Section 71 of the ALRA) in compulsorily leased Aboriginal lands[36]

- the ability of the Australian Government to remove the rights of an Indigenous person to even reside on compulsorily leased Aboriginal lands

- the uncertain relationship between the leases and other laws such as the Native Title Act.[37]

At the date of writing this Report, two years after the intervention was imposed in the Northern Territory, not a single house had been built.[38] No rent or compensation has been paid to the land owners.[39]

All the leases which were compulsorily acquired under the intervention will expire on 18 August 2012. However, I am concerned that the Government will then seek long-term leases from the traditional owners, which triggers the significant concerns I have already raised with the long-term leasing policy.[40]

1.3 The Rudd Government’s response – new promises, a fresh approach in 2008-09?

In order to gain a full appreciation of the native title system and land rights today, the remnants of the Howard Government’s policy approaches must be contemplated. Many aspects of these policies have continued under this Government. The concerns that I and previous Social Justice Commissioners have raised over that time remain disregarded.

Nonetheless, since the Government delivered the National Apology to the Stolen Generations,[41] it has introduced a number of reforms that will contribute to creating a new partnership between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This includes reviewing aspects of native title. As the Prime Minister has acknowledged, ‘[t]o speak fine words and then forget them, would be worse than doing nothing at all’.[42]

Eighteen months after becoming the Attorney-General, Robert McClelland stated native title reform is among his top priorities.[43] In December 2008, he admitted that he was ‘hoping to have made more progress in the first year’ to streamline native title processes.[44] In furtherance of the commitment to a more flexible and speedier native title system, he has stated that ‘Governments – including the Commonwealth – need to take a less technical and more collaborative and innovative approach to issues like connection’.[45]

To kick-start this process, the Attorney-General released two discussion papers throughout the year.[46] The Native Title Amendment Bill 2009 was introduced into Parliament, and inquired into by a Senate Committee.[47]

It is also apparent that further reform of the system is being contemplated.

For the first time in my five years as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, the Attorney-General has stated that his ‘mind is open’ to some more significant changes to the Native Title Act, such as shifting the burden of proof and providing for a presumption in favour of native title.[48] He has said that he is interested in ‘any constructive suggestions, especially those aimed at further encouraging agreement making’.[49]

In June 2009, he stated:

I believe there is real merit in exploring ways to build on reforms implemented to date to further simplify the native title system, to make resolving claims more efficient and timely, and to reinforce the principle that negotiation rather than litigation should be the primary mechanism for resolving native title claims. While legislative change is not a panacea, I am willing to explore ideas proposed... However, the Government will not rush into such changes without first consulting stakeholders... I am determined to ensure that the way we consult, and the relationships we forge along the way, distinguish this Government’s approach to native title.[50]

(a) The native title system in numbers

(i) Determinations between 1 July 2008 – 30 June 2009

Despite developments at a federal and state level, the native title system continued to operate at its usual pace: slowly. The NNTT confirmed that the timeframe within which matters are being finalised is not reducing,[51] and it expects that only 50 out of 473 native title matters will be determined within the next two years.[52]

During the 2008-09 reporting period, 12 determinations of native title were made by the Federal Court, bringing the total number of determinations since the Native Title Act began to 121. The determinations made in 2008-09 are detailed at Appendix 1.

This year’s determinations included the largest native title determination in South Australia, granting native title rights and interests over 41 000km2 of land in the Flinders and Gammon Ranges. The Adnyamathanha Aboriginal people lodged their claim in 1994. In 2009, they reached a consent determination with the state which recognises their rights to hunt, use natural resources, camp and conduct traditional ceremonies recognised over the majority of the area.[53]

The Nyangumarta People from Western Australia’s Pilbara region also had their native title rights and interests recognised over more than 33 843 km2 through two consent determinations. The claim was lodged in 1998. The mediation of this claim was considered by the NNTT to be ‘conflict-free’, during which ‘[n]o single issue turned into a tug-of-war’. Nonetheless, ‘the mediation still took two-and-half years to conclude after parties reached an in-principle agreement on the existence of the Nyangumarta native title rights and interests’.[54]

The NNTT member noted:

This relatively straightforward claim over unallocated crown land and pastoral leases has taken 11 years to reach an outcome, with some of the claim group no longer alive to see a result. The clear message is that more effort is needed to speed up the native title claims process.[55]

Another significant determination which was made was the Lardil, Yangkaal, Gangalidda and Kaiadilt Peoples who reached a consent determination, recognising their native title rights over 23 islands in Queensland’s Gulf of Carpentaria. The determination, which was made over the land, followed on from the 2004 determination that recognised the peoples’ native title rights to the sea.[56]

(ii) Resourcing the native title system

In previous native title reports I have raised serious concerns about the sufficiency and distribution of resources to bodies operating in the native title system. I have been particularly concerned about the impact that poor resourcing has had on the ability of NTRBs to adequately represent the interests of the Indigenous groups who are claiming native title. The Government has also acknowledged that NTRBs are significantly under-resourced.

On 12 May 2009, the Australian Government released its 2009-10 Budget. It committed an additional $50.1 million over four years to the native title system. This will be broken down to $45.8 million for NTRBs, and $4.3 million for the Government to look at ways to improve the system. This additional funding is welcome, and should go some way to lessen the pressure on NTRBs.

I was pleased to see $4.3 million set aside for examining ways to improve and streamline the operation of the system. As part of this, the Government has said it will look at:[57]

- more flexible connection evidence

- streamlining participation of non-government respondents

- improving access to land tenure information

- promoting broader and more flexible native title settlement packages

- initiatives to increase the quality and quantity of anthropologists and other experts working in the system

- partnerships with state and territory governments to develop new approaches to the settlement of claims through negotiated agreements.

Recognising that there are many lessons to be learnt from the first 16 years of native title, it is positive that the Government has allocated a pool of money to look at ways to address these serious shortcomings.

However, I have concerns with the adequacy of the allocation for NTRBs and PBCs.

Although the funding increase was given in response to a 2008 Native Title Coordination Committee’s review of funding of the native title system, the results of that review have not been made public. The Government has stated that the review ‘found that NTRBs were substantially under-resourced for the task they were expected to perform in the system’,[58] but the extent of that dearth in resourcing is not known. The Attorney-General has informed me that:

As the Native Title Coordination Committee’s 2008 review of funding of the native title system is confidential to Government, it is not possible to publicly release the recommendations. However, I can assure you that the Government did consider the recommendations in the context of the 2009-10 Budget process. The recommendations informed the decision to continue non-ongoing funding otherwise due to lapse in 2008-09, and to provide an additional $50.1 million over four years to improve the operation of the native title system.[59]

Having made submissions into the under-resourcing of NTRBs in the past, and knowing the results of previous reviews of NTRB resourcing, I would speculate that the 2008 review would have recommended a much greater funding increase than was provided in the 2009-10 Budget. I do not agree with the Attorney-General that this funding is sufficient to ensure that NTRBs are adequately resourced to participate in negotiations on behalf of Indigenous people.[60] This is particularly so given that the additional $50.1 million which has been allocated for a four year period, to be divided between all NTRBs across the country,[61] includes money for PBCs, and comes after a reduction of NTRB funding in the previous year’s 2008-09 Budget.

In fact, the provisional funding allocation for NTRBs for 2009-10 was over $5 million less than the funding provided to NTRBs for the 2008-09 financial year.[62]

In addition, despite my recommendation and calls for secured funding from across the country, the Budget did not provide a specific allocation for PBCs. Once again, PBC funding will come from the allocation for NTRBs, or from specific project funding from other agencies. I have been informed that in 2009-10, $1 million of the money allocated for NTRBs has been tentatively put aside for ‘crisis funding support for PBCs ... in recognition of the critical unmet needs that can arise in this area’.[63]

There are some sources of PBC project funding from other agencies. One such source is the Working on Country program run by the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. The 2009-10 Budget allocated $69 million to the Working on Country program to create 210 new Indigenous ranger jobs in remote and regional Australia over the next five years.[64]

There are various economic, cultural, social and environmental benefits that flow from enabling Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders to manage and care for their country. The new commitment of funds is welcomed.

Unfortunately project funds such as these rarely cover the operational costs of running a PBC or are inaccessible by PBCs due to an initial lack of funding and capacity. And so, despite running very successful programs, PBCs can struggle to find resources for telephones, offices and internet connections, seriously inhibiting their success. I comment further on the precarious positions of PBCs across the country later in this Chapter.

(b) Changes to native title over the year –the direction of the Australian Government

The Australian Government’s main message on native title this year is that it is dedicated to creating a native title system which encourages the parties to negotiate rather than litigate their claims. This policy would primarily be pursued through encouraging all parties to have a flexible and open minded attitude to settling native title claims.

I am supportive of this approach, and I am hopeful that it will lead to improved outcomes for Indigenous claimants. However, there are some serious barriers to change.[65]

Firstly, there are considerable constraints in the Native Title Act that will prevent parties making progress in improving native title outcomes. In Chapter 3 of this Report I consider some of these restrictions and possible amendments. Many of the restrictions originate from the initial scope of the Act. However the 1998 amendments made the situation significantly worse.

Secondly, ‘attitudes’ to policy are discretionary and depend on the elected government of each jurisdiction, creating uncertainty, unpredictability and inequity in native title outcomes across Australia. If a government changes, there is no guarantee that the flexible approach will be maintained. The different outcomes that result after a change in government or a change in a government’s approach have been seen many times.

Finally, I am concerned about the breadth of change that can be achieved when nearly all of the state and territory governments have indicated to me that they consider that they have already been acting in a flexible manner for years.[66]Subsequently, they all naturally support the Australian Government’s approach, but it begs the question, how much more flexible will these governments feel they can be within the existing framework?

The NNTT considers that while the Australian Government’s call for behavioural change is positive, it warns that even when parties support mediated rather than litigated outcomes, the support ‘has not always resulted in outcomes at a broadly acceptable rate’.[67] Nor has it always resulted in good outcomes.

These limitations are evident in the Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim, Part A of which was heard by the Federal Court throughout the year.[68] In that claim, the federal Attorney-General’s stated preference for flexible and less technical approaches to native title was not reflected in the Australian Government Solicitor’s approach to the claim, nor did the Queensland Government Solicitor act in a way that reflects the Queensland Government’s support for the federal Attorney-General’s flexible approach to native title.

In the view of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA), the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments’ attitudes in the claim were inconsistent with their policies and their commitments to act as model litigants.

...the Government lawyers continue to oppose the claim putting the Applicant to proof of its case. In the case of the Sea Claim the government parties’ position is captured by, among other things:

- A failure to make any significant concessions;

- Technical arguments regarding the nature and content of the native title rights and interests;

- Challenging the exercise, existence and extent of native title rights and interests in the whole of the claim area; and

- Pressing technical legal arguments that relate to questions of society and authorisation of the claim.

The position taken by the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments’ are disappointingly inconsistent with a commitment to ‘improve the operation of the native title system by encouraging more negotiated settlements of native title claims’. The position has caused TSRA to commit significant financial resources, time and other resources to prosecute the claim.[69]

This is a pertinent example of why relying on a change in attitude will not alone be sufficient to address the difficulties of the native title system. I recommend that the Australian Government pursue its policy through a combination of legislative and non-legislative options which together provide unambiguous and enforceable measures that all parties to native title must adhere to. Many of my ideas for change are identified in Chapter 3 of this Report.

Some measures initiated or completed by the Australian Government in 2008-09 are considered below.

(i) Native Title Amendment Bill 2009 (Cth)

After consulting on a discussion paper on minor native title amendments, the Attorney-General introduced the Native Title Amendment Bill 2009 (Cth) (the Bill) on 19 March 2009. The Native Title Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) (the Native Title Amendment Act) commenced on 18 September 2009.

The Amendment Act amends the Native Title Act to allow for, and encourage, broader negotiated agreements between native title claimants and other parties. The key changes include:

- giving the Federal Court full control over the management of native title claims

- giving the Federal Court the power to make consent orders about matters beyond native title. It is expected that this will assist with the negotiation of broader agreements

- giving the Federal Court the power to rely on an agreed statement of facts between the parties

- applying recent amendments to the Evidence Act broadly to native title proceedings[70]

- changing the provisions for recognition of NTRBs; and extension, variation and reduction of NTRB areas.[71]

I made submissions to the discussion paper and the Senate Inquiry, generally supporting the passage of the Bill.[72] I also recommended a number of improvements that could be made to the Bill and identified areas where further clarification of the law could be beneficial. In addition, I responded to the Attorney-General’s calls to provide additional concrete recommendations for reform of the native title system, and outlined in my submissions a number of other matters that require consideration in future reforms.

(ii) The Evidence Amendment Act 2008 (Cth)

In December 2008, the Evidence Amendment Act 2008 (Cth) was passed. The Act amends the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act), allowing for evidence of the existence or content of traditional law and custom to be exempt from the hearsay and opinion evidence rules. The amendments also changed the rules for narrative evidence, giving the court the power to direct a witness to give evidence wholly or partly in narrative form, rather than the standard question and answer format. This form of giving evidence is relevant for native title hearings where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people might be more comfortable giving evidence through narrative or in the traditional practice of ‘storytelling’. These amendments commenced on 1 January 2009.

I summarised these changes in my Native Title Report 2008.[73] I am pleased that changes introduced in the Native Title Amendment Act mean that the new evidence rules can apply to native title cases that began before 1 January 2009, if the parties consent or the Court orders that it is in the interests of justice to do so.[74]

However, I would like to reiterate the comments that I made in my Native Title Report 2008; that although the amendments to the rules of evidence may go some way to addressing the difficulties of evidence in native title proceedings, they will not provide a complete or adequate solution. For this reason I continue to advocate that the Evidence Act 1995 should not apply to native title proceedings.[75]

(iii) The Federal Justice System Amendment (Efficiency Measures) Bill (No 1) 2008 (Cth)

The Attorney-General introduced the Federal Justice System Amendment (Efficiency Measures) Bill (No 1) 2008 (Cth) into Parliament in December 2008. If passed, the Bill will allow the Federal Court to refer a proceeding, or one or more questions arising in a proceeding, to a referee for report.[76]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that this power could be useful where technical expertise is required, but it is not efficient for the judge to gain the necessary expertise in that area. Therefore, the Bill gives the Court the power to refer a matter out to a referee, which is intended to provide the Court with greater flexibility, and save on resources and time.

The Attorney-General considers that the Federal Court could use this power in native title cases, contributing to the Court’s ability to manage claims in such as way that the parties avoid protracted litigation and can negotiate outcomes. The new referral powers contained in the Bill may go some way to reducing the negative impacts that the adversarial setting has on native title claimants and the outcomes reached.

(iv) Optimising Benefits from Native Title Agreement-Making – Discussion Paper

The Attorney-General and the Minister of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs convened the Native Title Payments Working Group in July 2008 to ‘advise on how to promote better use of native title payments to improve economic development outcomes for Indigenous Australians’.[77] The Working Group on Native Title Payments reported to the Australian Government in late 2008.[78] The Attorney-General and the Minister for Indigenous Affairs then released a Discussion Paper that built on the working group’s report. The Discussion Paper considered legislative and non-legislative options that would ‘make better use of payments to Aboriginal communities under mining and infrastructure agreements’.[79] The proposals covered a range of topics, including transparency, taxation, minimum benefits, and other ways to promote good practice.

I agreed with aspects of the Discussion Paper, including the need to improve the application of the tax law to Indigenous corporations holding native title rights, or who receive benefits by virtue of a native title agreement.[80] However, I also recommended that the government focus on providing the Indigenous party to the negotiation with sufficient resources and access to the skills necessary to negotiate on an even playing field with the resource company. I would also like to see the underlying procedural rights on which negotiations are based, that is, the right to negotiate, expanded and strengthened to guarantee that even playing field.

Indigenous parties are on an unequal footing in negotiations with resource companies and governments. I have suggested changes to shift that power to create a more equal bargaining position for the Indigenous party. In turn, this will create better agreements. Communities know their own priorities. Once they have more power, they will be in a better position to pursue the outcomes they want to see achieved.

(v) Where momentum is waning

So far, I have considered areas where the Australian Government has made or considered changes to native title. However, there are areas of native title policy in which there has been a distinct lack of action and momentum. I consider examples of few such areas below.

Financial assistance to the states and territories for compensation

At the Native Title Ministers’ Meeting in 2008, state and territory Ministers agreed to negotiate in good faith on the content of an agreement between the Australian Government and themselves for financial assistance to deal with native title compensation.

The agreement was intended to be drafted by 30 June 2009.[81] At the date of writing, a copy of the agreement was not publicly available, nor had there been any comment by governments on its status.

In last year’s Native Title Report, I suggested that the Australian Government tie this funding to the behaviour of the state and territory governments in negotiating native title agreements, giving them incentive to act in the flexible manner that the Australian Government is advocating.

Joint Working Group on Indigenous Land Settlements - an alternative land settlement scheme

Another outcome of the Native Title Ministers’ Meeting in 2008 was the establishment of a Joint Working Group on Indigenous Land Settlements. The group is to:

- develop innovative policy options for progressing broader regional land settlements

- seek to complement, not override existing processes in place for the negotiation of flexible native title settlements.

The Government is pursuing these broader land settlements on the understanding that:

Broader settlement packages provide land and social justice outcomes beyond answering the question of whether native title exists. Examples of benefits under such settlements include training and employment opportunities, land transfers and co-management of land.[82]

Over the last year, the Joint Working Group has not produced any publicly available material. However, it is expected that the Working Group will report back to the next Native Title Ministers’ meeting in August 2009.

Indigenous Economic Development Strategy

Since it was elected, the Australian Government has talked about its impending Indigenous Economic Development Strategy. The Labor Party committed to developing an Indigenous Economic Development Strategy (IEDS) in their 2007 election campaign, highlighting economic development as a key feature of improving the lives of Indigenous Australians.[83] The Labor Party referred to the need for government to work in partnership with Indigenous people to achieve economic self-reliance for individuals and communities, and promoted links between Indigenous people and the private sector. Part of the IEDS would focus on housing, land and sea management and carbon trading.

When the Government was elected, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Jenny Macklin, regularly promoted the IEDS as the Government’s key policy platform for Indigenous affairs. In May 2008, Minister Macklin stated that the IEDS would be developed within six months.[84]

Again, in May 2009, Minister Macklin announced that the Government would soon release a public discussion paper outlining an approach to Indigenous economic development with an aim to incorporate that feedback into the IEDS, which would be launched later this year.[85] At the date of writing this Report, the Government had not released a discussion paper or a draft IEDS.

Prescribed Bodies Corporate – funding

All levels of government have failed to confront the problems concerning the viability of PBCs.

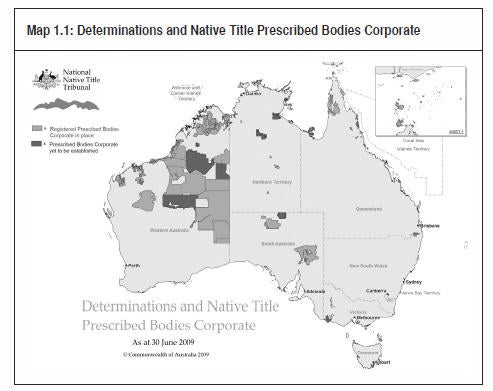

There are now over 60 registered PBCs in Australia.[86] The areas covered by PBCs are set out in Map 1.1. Under the Native Title Act, PBCs are established to hold native title once a determination has been made. However, they perform a wide range of ever-expanding functions. Given that the native title rights and interests held by PBCs are not able to be used for commercial gain, PBCs often struggle to fund their basic administrative and organisational costs. This undermines their capacity to comply with complex regulatory and project reporting requirements. This, in turn, threatens their ability to protect the native title rights they were established to maintain.[87]

| Map 1.1: Determinations and Native Title Prescribed Bodies Corporate |

The chair of a PBC in Western Australia describes the difficult position that PBCs are placed in:

The PBC is the foundation to look after our land, our culture, socially and economically...In the last couple of years our committee has been struggling a little. Our [Annual General Meeting] has been failing a bit. I have got to look at every little avenue to manage our country. How can we manage our country without government funding? We set up lots of Karajarri projects with project funding... The government says ‘we will give you money for the project, but we won’t give you money for the PBC’. ... The downfall of our PBC is trying to administrate and manage our country. We have no fax, no phone, and no place where people can come.[88]

Yet, as I mentioned earlier in this Chapter, no federal funding has been allocated specifically for PBCs. The 2007 changes to the native title system did provide that NTRBs could use some of their limited funding to assist PBCs with their day-to-day operations. Through this mechanism, approximately $1 million of NTRB funding has been set aside for PBCs across the country in 2009-10.[89] The 2007 changes also allowed for the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) to consider direct funding requests from PBCs. To date, FaHCSIA has not directly funded a single PBC.[90]

The 2007 amendments to the Native Title Act also provided for another potential funding source for PBCs. PBCs are now able to charge fees for the costs that they incur in respect of a number of matters that are specifically listed in subsection 60AB(1) of the Native Title Act. These include costs incurred when negotiating agreements under s 31(1)(b) of the Native Title Act and negotiating Indigenous Land Use Agreements.[91]

Regulations can be made to allow PBCs to charge a fee for costs they incur when performing other functions.[92] However, two years after these amendments were finalised, these regulations are yet to be drafted.

Overall, the Australian Government has acted contrary to the Australian Labor Party’s National Platform and Constitution 2007, which commits to ensuring adequate resourcing for the core responsibilities of PBCs.[93]

In the meantime, pressure is building on PBCs to perform a myriad of tasks on behalf of every level of government. This takes advantage of the traditional owners’ sense of responsibility to their country.

For example, amendments were made in 2008 to the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Qld) and the Torres Strait Islander Land Act 1991 (Qld). Previously, lands granted by the Queensland Government to Indigenous communities were administered by a trustee for the benefit of Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islanders particularly concerned with the land.

The 2008 amendments made a number of significant changes to the Queensland land rights Acts, including allowing Registered PBCs to hold the land for the native title holders of that land. The Acts now allow the Minister to appoint a PBC as the grantee of the land if there is a determination over all or part of the land, and the PBC approves. These amendments were intended to assist the Queensland Government to include Indigenous land as part of native title negotiations and to help align the Queensland Acts with the Native Title Act.[94]

Despite this significant additional responsibility, the Queensland Government has not committed to providing additional resources to enable PBCs to undertake this responsibility. The Government has only committed to providing guidance to new grantees as to how to enter into leases. I have been told that the Queensland Government considers that PBCs are the funding responsibility of the Australian Government, as a federal law (the Native Title Act) requires PBCs to be established. I do not agree with this approach. PBCs are established to hold and protect native title rights and interests under the Native Title Act. However, that does not mean that they should be asked to shoulder additional responsibilities, programs and costs by other governments, without appropriate resources to undertake those additional responsibilities.

As I have stated, many PBC members would be loathe to not accept the responsibilities to deal and manage their land. This is exactly what they have worked toward in pursuing their native title claim. Yet they must be funded to undertake this role. Otherwise, they are being set up to fail yet again.

Given these pressures, PBC members are banding together and demanding practical recognition of their status as the traditional owners of an area.

One aspect of this is that they would like to form a national peak body in order to form a direct line of communication with governments about land and sea matters and the management of their native title rights and interests. At a meeting of over 50 PBC representatives, PBCs called for a peak body which would be the voice for PBCs, coordinate information, mentor new PBCs, lobby and influence policy and sit with other national bodies.[95]

I support this call. I recommend that such a body should be supported by existing bodies and projects that play a similar role. This could include the Aurora Project, the PBC project at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) and the National Native Title Council (NNTC).

I also consider that further attention needs to be paid to the development of sources of funding support for PBCs. Funding models already exist whereby a percentage of income derived from state land tax or mining activity has funded the statutory land rights regime. Some land rights regimes across the country are now self-funding due to state government investment. The examples featured in Text Box 1.1 should be further reviewed to determine what aspects may be appropriate for the native title system to create financial sustainability for land holding and management organisations once a determination has been made.

| Text Box 1.1: Examples of funding arrangements for land rights regimes |

|

New South Wales Land Rights Regime[96] Under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), an account was established, whereby for fifteen years, the state paid an amount equivalent to 7.5% of NSW Land Tax (on non-residential land) into statutory accounts administered by the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC), as compensation for land lost by the Aboriginal people of NSW. That annual payment ceased in 1998 when a clause in the Act, known as the Sunset Clause, took effect. Since then, the NSW Aboriginal Land Council has been self-sufficient, funding its activities and supporting Local Aboriginal Land Councils with the money made from its investments. The capital, or compensation, accumulated over the first 15 years of the Council's existence remains in trust for the Aboriginal people of NSW and cannot be touched. Interest from NSWALC’s investments fund the organisation’s head office in Parramatta, which oversees and funds the network of Local Aboriginal Land Councils. NSWALC also funds land claims, related test-case litigation and supports the establishment of commercial enterprises which create an economic base for Aboriginal communities. Aboriginals Benefit Account - Northern Territory[97] The Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) is a Special Account (for the purposes of the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (Cth)) established for the receipt of statutory royalty equivalent monies generated from mining on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory (NT), and the distribution of these monies. The ABA is administered by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs in accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth). The ABA funds are used to meet the operational costs of the Land Councils in the NT and to pay compensation to traditional owners and other Aboriginals living in the NT that have been affected by mining. The ABA can also make grants for the benefit of Aboriginal people in the NT and in exercising this function, the Commonwealth Minister receives advice from an Account Advisory Committee with Aboriginal majority membership. |

Government support at all levels is crucial to the success of the system overall and to meeting the goal of closing the gap.

Prescribed Bodies Corporate – regulation

Since its commencement in 2007, I have raised concerns about the application of the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) (the CATSI Act).[98] I have previously:

- called for a review of the impact of the CATSI Act on Indigenous corporations, in particular on the ability of Registered Native Title Bodies Corporate (also known as PBCs)[99] to protect and utilise their native title rights and interests

- recommended that the Government ensure that funding provided to registered PBCs is consistent with the aim of building the capacity of PBCs to operate.

Those recommendations have not been addressed.

FaHCSIA has advised that $545 750 was provided to NTRBs during the 2008-09 financial year for allocation to specific PBCs. In addition, FaHCSIA advised that the ORIC also expended $1.5 million in training to Indigenous corporations, some of which was provided to PBCs. ORIC organised and funded five workshops for PBCs, which were attended by 15 groups during the 2008-09 financial year.[100]

While I acknowledge and support the critical work of the ORIC in developing the governance capacity of Indigenous organisations (including PBCs), I am concerned that at least two registered PBCs have been placed under administration during this reporting period.[101] This emphasises the need for a review of the impact of the CATSI Act on Indigenous corporations.

1.4 Significant cases affecting native title and land rights

(a) The constitutional validity of compulsory acquisitions under the Northern Territory intervention: Wurridjal v Commonwealth

(i) Background

In February 2009, the High Court handed down its decision in Wurridjal.[102] In the case, the Court considered the constitutional validity of certain provisions of the legislation which supported the Northern Territory intervention.[103]

Two senior members of the Dhukurrdji people (traditional owners of an area including the town of Maningrida) and a business in Maningrida (the Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation) argued that three aspects of the intervention were acquisitions of property under the Constitution:

- the compulsory acquisition of five-year leases over township land in Aboriginal communities across the Northern Territory[104]

- changes to the permit system, which stated that permits were no longer required to enter common areas of community land nor the roads connecting them[105]

- the alleged subordination of Aboriginal people’s rights to enter upon and use or occupy the land in accordance with Aboriginal tradition.[106]

More than a year after the intervention began no rent or compensation for the changes had been discussed with traditional owners or the Land Councils.[107]

(ii) Arguments of the parties

In the High Court, the plaintiffs claimed that the Commonwealth had acquired Aboriginal property rights on other than just terms, in breach of the guarantee offered to property-holders in s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution.[108] They sought a declaration that, to this extent, the intervention legislation was invalid.

The Commonwealth claimed that because the intervention legislation was made under the Territories power of the Constitution (s 122),[109] the safeguard of just terms for the acquisition of property in s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution did not apply.

In the alternative, the Commonwealth claimed that no property was acquired because the Land Trust’s fee simple interest in the land was a mere statutory entitlement (created under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (the ALRA)) and therefore it was defeasible and could be changed by another Commonwealth law. They argued that the changes that were made for the intervention were less than an ‘acquisition’, because under the ALRA the Commonwealth continued to have a significant level of control over Aboriginal land.

Finally, in the event that the Court held that there was an ‘acquisition of property’ in the constitutional sense, the Commonwealth argued that the provisions in the intervention legislation which allowed court action to recover reasonable compensation, satisfied the requirement for ‘just terms’.

(iii) Decision of the High Court

Therefore, the High Court considered three issues:

- Whether the requirement for just terms compensation in s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution applies to laws made for the territories under s 122 of the Constitution.

- Whether there had been an acquisition of property.

- Whether the relevant laws provided just terms.

A majority of the Court answered ‘yes’ to all three.[110] The majority overruled Teori Tau v Commonwealth (Teori Tau),[111] in which the Court had held that s 122 is not limited or qualified by s 51(xxxi). They found that there had been an acquisition of property to which s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution applied.

However, the majority also found that the intervention legislation provided just terms, by allowing recovery of ‘reasonable compensation’, if necessary by court action. Although the plaintiffs ‘won’ on two of the three questions argued before the Court, the Court required them to pay the Commonwealth’s legal costs.

(iv) Justice Kirby’s dissent

Justice Kirby dissented on the overall result in Wurridjal. He found that the applicants should not be knocked out in a preliminary hearing of the kind adopted by the High Court (a ‘demurrer’), which addressed legal questions divorced from a full trial involving witnesses and other evidence. He was satisfied that the plaintiffs had an arguable case (particularly with a majority over-ruling Teori Tau) and should have the opportunity, after amending and clarifying their claim if necessary, to pursue the matter in a full hearing. As Kirby J stated:

My purpose in these reasons is to demonstrate that the claims for relief before this Court are far from unarguable. To the contrary, the major constitutional obstacle urged by the Commonwealth is expressly rejected by a majority, with whom on this point I concur. The proper response is to overrule the demurrer. We should commit the proceedings to trial to facilitate the normal curial process and to permit a transparent, public examination of the plaintiffs’ evidence and legal argument... The law of Australia owes the Aboriginal claimants nothing less. ...

If any other Australians, selected by reference to their race, suffered the imposition on their pre-existing property interests of non-consensual five-year statutory leases, designed to authorise intensive intrusions into their lives and legal interests, it is difficult to believe that a challenge to such a law would fail as legally unarguable on the ground that no “property” had been “acquired”. Or that “just terms” had been afforded, although those affected were not consulted about the process and although rights cherished by them might be adversely affected. The Aboriginal parties are entitled to have their trial and day in court. We should not slam the doors of the courts in their face. This is a case in which a transparent, public trial of the proceedings has its own justification.[112]

Justice Kirby attributed legal significance to the indigeneity of the traditional owners. By contrast Justices Hayne and Gummow stated:

No different or special principle is to be applied to the determination of the demurrer to the plaintiffs’ pleading of invalidity of provisions of the Emergency Response Act and the FCSIA Act because the plaintiffs are Aboriginals. No party to this litigation sought to rely upon any such principle, whether the suggested principle be described as a rule of ‘heightened’ or ‘strict’ scrutiny or in some other way. There was therefore no examination of the content of any such principle. But we would agree that such a principle ‘seems artificial when describing a common interpretative function’. In any event, to adopt such a principle would have departed from the fundamental principle of ‘the equality of all Australian citizens before the law’...[113]

Recognising another consequence of the special status of traditional owners compared to other land owners in Australia, Justice Kirby reiterated his comments in the Griffiths[114] case in which he emphasised that Indigenous peoples’ rights deserve special protection and that any law purporting to extinguish or diminish Indigenous peoples’ land rights can only do so by ‘specific legislation’ which expressly states this intention.[115]

He supported this principle with a discussion of relevant international law which ‘recognises the entitlement of indigenous peoples, living as a minority in hitherto hostile legal environments, to enjoy respect for, and protection of, their particular property rights’.[116]

Justice Kirby concluded:

In these proceedings a growing body of international law concerning indigenous peoples exists that confirms the rules that are already now emerging in Australian domestic law. Laws that appear to deprive or diminish the pre-existing property rights of indigenous peoples must be strictly interpreted. This is especially so where such laws were not made with the effective participation of indigenous peoples themselves. Moreover, where (as in Australia) there is a constitutional guarantee providing protection against ‘acquisition of property’ unless ‘just terms’ are accorded, development of international law will encourage the national judge to give that guarantee the fullest possible protective operation.[117]

The plaintiffs’ status as traditional owners also influenced Justice Kirby’s consideration of what actually constitutes just terms. He referred to case law and the differences between the Australian Constitution and the drafting of the Constitution of the United States of America to support his view that ‘[a]t least arguably, “just terms” imports a wider inquiry into fairness than the provision of “just compensation” alone’.[118]

Justice Kirby considered the implications of this view for the acquisition of traditional owners’ land. He stated that:

This might oblige a much more careful consultation and participation procedure, far beyond what appears to have occurred here. ...

Given the background of sustained governmental intrusion into the lives of Aboriginal people intended and envisaged by the National Emergency Response legislation, ‘just terms’ in this context could well require consultation before action; special care in the execution of the laws; and active participation in performance in order to satisfy the constitutional obligation in these special factual circumstances ...[119]

(v) Significance of the decision

The decision of the High Court in Wurridjal is significant for several reasons. A majority of judges over-ruled Teori Tau and said effectively that the just terms guarantee applies in the territories in the same way that it does in the states. This is important for everyone who lives in a territory and is therefore subject to Commonwealth laws passed under s 122 of the Constitution. I am particularly pleased that a majority recognised the unfairness of the rule in Teori Tau, because Aboriginal people make up almost 30% of the population in the Northern Territory and they hold fee simple (or freehold) title to almost 50% of the land there. These property rights were vulnerable to second-class treatment by the Commonwealth under the old law.

As I noted earlier, in Wurridjal the Commonwealth argued that it retained such a strong controlling interest over Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory that it could impose a five-year lease against the wishes of traditional owners (with apparently no obligation to pay rent) and yet not trigger the obligation to provide just terms. Another welcome feature of the case is that a majority of the Court rejected this argument. The decision reaffirmed the legal strength of Aboriginal property rights under the ALRA and the independent degree of control over land enjoyed by traditional owners.

On the other hand, the case has left some important questions unanswered about the ‘valuation’ of Aboriginal property rights and the legitimacy or otherwise of applying normal ‘real estate’ principles regarding compulsory acquisition and compensation to these unique property interests. Because of the way the case was dealt with, the plaintiffs’ arguments that special procedures for acquisition and non-monetary compensation might be required to meet the constitutional standard of just terms remain unresolved.

It is also unclear from the Court’s decision whether the changes to the permit scheme, on their own, effect an acquisition of property. This remains important for the future, particularly if further unilateral changes are made by Parliament to the rules for entering on Aboriginal land or the permit changes remain in place after expiry of the five-year leases.[120]

The Government is accountable for the arguments that its legal representatives put before courts. The Commonwealth’s arguments in this case raise a number of concerns about the Government’s approach to Indigenous peoples’ land rights.[121]

The Government disputed whether any compensation needed to be paid simply because the acquisitions were in the Northern Territory.

Perhaps even more concerning was the Government’s alternative argument that five-year leases were a statutory readjustment and not an acquisition of property. This can be seen as an attempt by the Commonwealth to treat Aboriginal land as an inferior form of title.

A further concern remains about the Commonwealth Government’s conduct – the failure to pay rent and compensation for the leases in a timely manner.

In October 2008, well after proceedings in this case had commenced, the Government requested the Northern Territory Valuer-General to determine the rents that should be paid for the compulsory five-year leases.

On 27 February 2009, about a month after the Wurridjal decision was handed down, the Government announced that it had finalised boundaries for all 64 five-year leases that were acquired by the Government as part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response. The review of the lease boundaries resulted in changes to the leases to reduce the area leased and allowed for the Government to accurately determine the area for which they would pay rent. The Minister for Indigenous Affairs, stated that the Government recognised ‘that reasonable rent must be paid to landowners’.[122]

In August 2009, the Minister advised me that:

In October 2008, in response to the recommendation of the Northern Territory Emergency Response Review Board, I wrote to the Northern Territory Valuer-General requesting that he determine reasonable amounts of rent to be paid to owners of land subject to five-year leases under the NTER. In March of this year, I made an additional request of the Valuer-General to also determine rent to be paid under the reduced lease boundaries that came into effect on 1 April 2009. The Valuer-General was asked to give these requests his prompt attention. I am advised that the Valuer-General is currently finalising his draft report, a copy of which will be provided to FaHCSIA as well as the relevant land councils for comment. I expect to receive the Valuer-General’s final report containing both sets of determinations in late August 2009. The payment of rent will commence shortly after.[123]

At the time of writing this Report, the Government had still not paid rent or compensation for the leases.

I further consider the Government’s approach regarding the payment of rent and the assessment of compensation in Chapter 4 of this Report.

I am also concerned that the Commonwealth drafted compensation provisions which required a full-scale constitutional case to establish entitlements and yet, when the Aboriginal parties defeated the Commonwealth on two out of three constitutional arguments, they were nonetheless ordered to pay the Commonwealth’s legal costs.

Only Kirby J considered that the costs order was unjust:

They brought proceedings which, in the result, have established an important constitutional principle affecting the relationship between ss 51(xxxi) and 122 of the Constitution for which the plaintiffs have consistently argued. It was in the interests of the Commonwealth, the Territories and the nation to settle that point. This the Court has now done. In my respectful opinion, to require the plaintiffs to pay the entire costs simply adds needless injustice to the Aboriginal claimants and compounds the legal error of the majority's conclusion in this case.[124]

The end result is inequitable. Between the calculated drafting strategy of the Commonwealth and the costs order of the Court, the law seems to have operated unfairly.

(b) The requirement to negotiate in good faith: FMG Pilbara Pty Ltd v Cox

(i) The future act regime

The future act regime deals with proposed development on native title country. Particular forms of development likely to have a substantial native title impact attract additional procedural protections for native title parties. These protections are known as the ‘right to negotiate’ and they apply to the grant of some mining tenements (leases and licences) and certain compulsory acquisitions. The Act places emphasis on negotiation as the means for addressing the native title issues at stake in such future acts, by preventing resort to an arbitral body (usually the NNTT) for a period of six months. Time runs from the issue of a notice that the government intends to grant a mining tenement (s 29 notice). During this negotiation window, s 31 of the Native Title Act obliges the parties involved to negotiate in good faith. The main negotiating parties are the mining company (grantee) and a registered native title claimant group or the recognised native title holders for the area, with the state or territory government playing a passive or sometimes more active role as well.

In FMG Pilbara[125] (decided in April 2009), the Full Federal Court considered what is required for parties to fulfil the obligation in s 31 to ‘negotiate in good faith with a view to obtaining the agreement of each of the native title parties to the doing of the act or the doing of the act subject to conditions’.[126]

(ii) Background to the appeal

The Western Australian Government gave notice of its intention to grant Fortescue Metal Group (FMG) a lease to mine an area in the Pilbara region. The proposed lease overlapped a registered native title claim and an area where native title had been determined.

As required by the Native Title Act, FMG negotiated with both native title parties – the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura People (PKKP), a registered native title claimant group for part of the area, and the Wintiwari Guruma Aboriginal Corporation (WGAC), the registered native title body corporate for the balance of the area.[127] Six months after the notice, none of the parties had reached an agreement. FMG applied to the NNTT for a determination whether the future act could proceed, with or without conditions. Both the native title parties alleged that FMG had not fulfilled its obligation to negotiate in good faith.

FMG had approached the negotiations on a ‘whole of claim’ basis. That is, the miner sought a comprehensive Land Access Agreement (LAA) that bundled together not only the specific grant of the mining lease in question, but all the other future activities it might wish to undertake on the native title land in question, in pursuit of exploration and mining projects. This included obtaining tenure for mining as well as for railway and port infrastructure, and the authority to extract water.

Most of the discussions between PKKP and FMG had concerned the finalisation of a negotiation protocol, an agreed process for dealing with these comprehensive negotiations. PKKP claimed there had only been one meeting following the conclusion of the negotiation protocol about the substance of FMG’s proposed activities.

The native title parties drew attention to a number of aspects of FMG’s behaviour, raising two questions in particular about the obligation to negotiate in good faith: