Social Justice Report 2003: Chapter 2: Reconciliation and government accountability

Social Justice Report 2003

Chapter two: Reconciliation and government accountability

In the Social Justice Report 1999,

my first report as Social Justice Commissioner, I identified four key

themes and challenges that existed in the approach of the federal government

to Indigenous policy making at the time. These were moving beyond welfare

dependency, accountability, participation and reconciliation.[1] Since the release of that report approximately four years ago, the key

themes and challenges facing the government have remained relatively constant.

The fundamentals of the government's approach to Indigenous affairs have

not changed substantially, with only subtle refinements and a locking

down of their approach across all program and policy areas and at the

inter-governmental level. These refinements have taken place through the

consistent use of coded language such as 'practical reconciliation', 'mutual

obligation', 'agreement making' and 'partnerships', and more recently

'shared responsibility'.[2]

To the phrase 'moving beyond welfare dependency'

we could now add 'sustainable development', 'capacity building' and 'mutual

obligation'. For 'accountability' we could add 'governance reform', 'shared

responsibility', 'whole of government approach' and 'changing the way

we do business with Indigenous communities'. For 'participation' we could

add 'self-management', 'agreement making' and 'partnerships'. For 'reconciliation'

we can directly substitute 'practical reconciliation' and divide issues

into so-called real and symbolic ones.

The next two chapters examine current progress

in addressing a range of issues in relation to these four themes. They

consider the adequacy of the structures and processes that have been put

into place at the national level to progress programs and services to

Indigenous peoples; and ultimately, based on this analysis, identify an

agenda for change with recommendations to improve Indigenous policy and

program design. This chapter focuses on developments relating to reconciliation

and mechanisms for government accountability. Chapter 3 then focuses on

the participation (and accountability) of Indigenous organisations and

peoples in government activity and developments relating to the objective

of moving Indigenous peoples beyond welfare dependency. The subject matter

of the two chapters is inter-related and together they constitute my annual

progress report on reconciliation.

Reconciliation

In 2003, there have been three main sets

of developments in relation to the government's approach to reconciliation.

First, there has been continuity in the implementation of programmes and

in the policy direction of the federal government towards reconciliation.

The primary focus of activity during the year has been on advancing initiatives

that were announced or committed to in either 2002 or previous years (such

as through the Council of Australian Governments' Communiques on Reconciliation

in 2000 and 2002).

There has been a high level of commitment

by the federal government to continuing to implement programmes in accordance

with its 'practical reconciliation' agenda. There have been significant

developments in implementing the commitments of the Council of Australian

Governments (COAG) to conduct a number of whole-of-government community

trials across Australia and to establishing an annual reporting framework

on Indigenous disadvantage. There has also been an increased focus on

debilitating problems affecting Indigenous communities such as family

violence, with the convening of a national summit by the Prime Minister

and the announcement of new funding for programs to address it (these

were described as a 'down-payment' and are expected to be backed up with

further funding in the 2004 Budget).

Second, and concurrent to this continuation

of the existing approach, has been public debate about the adequacy of

accountability mechanisms for government service delivery to Indigenous

peoples and for reconciliation. Specifically in relation to reconciliation,

this debate has taken place through the Senate Legal and Constitutional

References Committee's inquiry into national progress towards reconciliation

and through the commencement of the second reading debate in the Senate

on the Reconciliation Bill 2001 (which seeks to introduce monitoring

and evaluation processes for reconciliation, in accordance with the recommendations

of the final report of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation). Through

both of these processes the government has revealed that it considers

it unnecessary to introduce formal legislative monitoring mechanisms for

progress towards reconciliation at the national level.

In more general terms, this debate has taken

place through the review of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Commission (ATSIC). The review process saw a clear expression of dissatisfaction

with progress in addressing the disadvantage experienced by Indigenous

peoples and in government service delivery to Indigenous peoples, as well

as at the perceived failure of ATSIC to effectively represent Indigenous

peoples. The findings and recommendations of this review are discussed

in detail in the next chapter. Of note here, however, is that while the

review was intended to review mechanisms for service delivery to Indigenous

peoples (i.e., not to be solely focused on ATSIC) its ultimate focus from

an accountability perspective was on the role of ATSIC. It provided only

limited focus on accountability mechanisms and the responsibilities of

the rest of government.

The third main set of developments in relation

to the government's approach to reconciliation has been that the limits

of practical reconciliation were exposed through a number of processes

and events during the year. These included the Senate Legal and Constitutional

References Committee's inquiry into national progress towards reconciliation,

the release of data from and analysis of the 2001 Census, the release

of the first national report on overcoming Indigenous disadvantage by

the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision,

and the public debates about service delivery to Indigenous peoples that

took place as part of the ATSIC Review.

The Social Justice Report 2002 had noted that the dominant feature of the government's approach to reconciliation

and Indigenous affairs the previous year was the refinement and bedding

down of its 'practical reconciliation' approach.[3] The report expressed the concern that 'by continually reinforcing that

its commitment is to addressing key issues of Indigenous disadvantage

and nothing else' the government had 'developed a tunnel vision that renders

it incapable of seeing anything that falls outside the boundaries that

it has unilaterally, and artificially, established for relations with

Indigenous peoples'[4] . It also expressed

the concern that as a consequence of this, the limited processes that

existed for accountability were not directed to those issues with which

the government did not agree or which fell outside of its limited approach.

In the remainder of this chapter, I examine

key developments relating to reconciliation at the national level during

2003. The focus of this progress report is on the adequacy of processes

for accountability of the government for reconciliation, particularly

as they relate to 'practical' reconciliation.

National progress towards reconciliation in 2003

- Key developments

This section considers developments over

the past year relating to reconciliation under the following headings:

- A 'highly controlled' commitment to 'practical' reconciliation;

- Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage; and

- Implementing the commitments of the Council of Australian

Governments.

a) A 'highly controlled' commitment to 'practical'

reconciliation

On 27 November 2003, the Senate began the

second reading debate on the Reconciliation Bill 2001. The Bill

was identical to that included in the final report of the Council for

Aboriginal Reconciliation and which the Council had recommended should

be passed by the Parliament in order to provide a legislative framework

to deal with the unfinished business of reconciliation. The Bill was first

introduced by Senator Ridgeway on 5 April 2001, with debate on the Bill

adjourned that same day. It has taken more than two and a half years for

the Bill to be reconsidered and reach the second reading stage in the

Senate.[5]

As Senator Ridgeway noted in his second

reading speech, the Bill provided 'an opportunity to debate essentially

what the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation recommended'.[6] It was the first extensive debate to take place directly on

reconciliation in the Senate chamber since the Council released its report

in December 2000 (notwithstanding the debates that took place through

the parliamentary committee system with the Senate Legal and Constitutional

References Committee's inquiry into reconciliation and estimates processes).

The debate on the Bill was acrimonious.

The opposition parties stated that 'there has been a clear lack of responsibility

on the part of the government which ...seems to be intent on destroying the

spirit of what reconciliation is about by putting forward a policy of

practical reconciliation';[7] that reconciliation

'is clearly an issue that has fallen off the Howard government's agenda';[8] and that the government has a 'record of not performing when it comes

to reconciliation in this country'. [9]

Government Senators responded angrily to

these comments. One government minister interjected that criticisms of

the government's performance were 'sanctimonious rubbish' and that 'you

could be a bit gracious and comment on some of the positive things'.[10] Another member of the government accused a fellow Senator of being 'one

of the phoney people ... There is a lot of phoniness in this debate. People

come in here and make symbolic speeches and then go home and forget about

it. You want to live it'.[11]

A striking feature of the debate is the

deeply impassioned nature of the speeches made by members of the government

and their outrage at the suggestion that the government is not committed

to reconciliation. Senator Ferris put the position of the government as

follows:

If one were to listen to the contribution of (the Opposition) ...

one would believe that reconciliation is dead in this country. Nothing

could be further from the truth. Reconciliation between Indigenous

Australians and the wider community is an objective that the federal

government is fully committed to, and all of us on this side of the

chamber are fully committed to. The Australian government strongly

reaffirms its support for reconciliation, as expressed in the historic

motion of reconciliation that was passed by both houses of the federal

parliament on 26 August 1999 ... [T]his motion confirmed a whole-hearted

commitment to reconciliation as an important national priority for

all Australians.'[12]

There is a subtle but important factor illustrated

by comments such as these that must be acknowledged about the government's

approach to reconciliation. Members of the government are committed to

achieving reconciliation. Analyses of how the government is performing

on reconciliation, such as this report, do not seek to present the government's

position as if it were opposed to achieving reconciliation. Instead, the

crucial issue is the nature of the commitments made by the government

and whether they are sufficient (or in other words, do they progress reconciliation

or instead impede progress, either through commission or omission?).

Senator Ferris explained what the government

means by reconciliation in the debate on the Reconciliation Bill as follows:

Of course, the concept of reconciliation is one that

means different things to different people ... But there is one common

thread to people's view of reconciliation in this country and that is

that all Australians are entitled to equal life chances, to equality

of opportunity, and that true reconciliation will not exist until Indigenous

disadvantage has been eliminated. The very sad truth is that Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia still remain the most

disadvantaged group in our society ... despite the best efforts of hundreds,

perhaps thousands of individuals in this country over many years ...

The federal government believes that the best way

it can act to achieve reconciliation is through the provision of practical

and effective measures that address the legacy of profound economic

and social disadvantage that are experienced by many Indigenous Australians,

particularly in those crucial areas of health, education, housing and

employment. Practical measures in these key areas have a positive effect

on the everyday lives of Indigenous Australians.'[13]

I have extensively criticised this approach

to reconciliation in the Social Justice Reports for 2000-2002.'[14] At core, concerns about the government's approach to reconciliation focus

on the limited scope of the commitments that they make; the lack of a

process for dealing with issues that fall outside the parameters set by

the government; the derisive and somewhat arbitrary way that the government

discards issues which it does not agree with as 'symbolic' and then simply

ignores them; and the lack of a rigorous monitoring framework to hold

the government accountable for its commitments and for any lack of progress

in areas which it has chosen to ignore.

The government's approach to reconciliation

is also malleable. In 2003, for example, the design and wording for a

memorial on the stolen generations for inclusion at Reconciliation Place

in Canberra was agreed between the government and the National Sorry Day

Committee.'[15] While there is a clear preference

for 'practical' measures of assistance rather than 'symbolic' measures,

the government's approach does involve and recognise the importance of

such symbolic measures. It is often not clear, however, why particular

issues are acceptable and fall within the parameters of practical reconciliation

while others do not.

These concerns about the government's approach

do not, however, suggest that there is an absence of a commitment to reconciliation.

Instead they identify that this commitment is to a particular type of reconciliation around which the boundaries are tightly proscribed by

the government.'[16]

Jackie Huggins has effectively addressed

the issue of the nature of the government's commitment to reconciliation

as follows:

There is little doubt that the current Government in

Canberra would like to make an impact in Indigenous affairs, though

its vision of a reconciled Australia would be very different to that

of many of us ... Although, there are strong indications that Ministers

across a number of Commonwealth portfolios are becoming more open

to looking at creative solutions to persistent problems.

But the bottom line for this Prime Minister and his

governmental has always been the compartmentalising of reconciliation

and Indigenous affairs into so-called practical and symbolic measures,

the latter having been rejected as unacceptable to mainstream Australia ...

In this highly controlled context ... it is true to say

that many in the community have been left with the impression that

the reconciliation agenda in Australia has run into the sand. Others

have been basking in the mistaken belief that reconciliation has already

arrived. The truth is somewhere in between ...'[17]

The continuity over several years of this

'highly controlled' approach of the government towards reconciliation

has inevitably seen policy debates shift towards the government's framework.

This was increasingly the case in 2003. Progressively each year has seen

less focus on issues that do not fall within the government's approach,

such as an apology, the plight of the stolen generations, the treaty debate

and native title. As Reconciliation Australia notes, these issues 'have

not gone away however those involved in reconciliation have chosen to

engage with the government where constructive progress can be made'.'[18] This reflects political reality rather than an embracing or endorsement

of the government's position. As Jackie Huggins has noted:

Those of us involved in reconciliation and Indigenous

affairs have had to make a choice about whether to keep beating our

heads against a wall on ... issues (of unfinished business) ... or whether

we look to what can be achieved in the political context in which

we find ourselves, and try to move forward. And that is the choice

we have made. We have a responsibility to keep the rest of the agenda

alive but we also have a duty to engage and to continue to progress

things that can be progressed.'[19]

Similarly, processes for sustaining and

monitoring progress towards reconciliation are increasingly focused on

'practical' reconciliation. In 2003, the Senate Legal and Constitutional

References Committee concluded its inquiry into national progress towards

reconciliation and made several recommendations to implement a broader

approach to reconciliation which incorporates all aspects of reconciliation

that were identified by the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation'[20] A similarly based debate also commenced in the Senate on the Reconciliation

Bill 2001. The government has indicated that it does not consider

the mechanisms in either of these processes as necessary, on the basis

that it already has mechanisms in place for progressing practical reconciliation.

Consequently, it is unlikely that there will be mechanisms introduced

which will enable issues that do not fit exactly within the government's

framework to be advanced.

b) Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage

The government has emphasised time and again

that the key focus of reconciliation should be on practical and effective

measures that address the legacy of profound economic and social disadvantage

that is experienced by many Indigenous Australians. As quoted above, the

government's position is that 'true reconciliation will not exist until

Indigenous disadvantage has been eliminated'.

Newly released data in 2003 provided the

opportunity to establish whether we are progressing towards this ultimate

goal of the government's reconciliation agenda and to determine whether

the pace of such progress is adequate.

The Social Justice Reports for

2000 through to 2002 raised a number of challenges for the government

in order to determine whether they are meeting their commitment to address

the social and economic inequality experienced by Indigenous Australians.

These challenges include the establishment of benchmarks and targets which

commit to a rate of progress in improving the socio-economic conditions

of Indigenous peoples and improved data collection to enable such progress

to be more accurately measured. There have been some developments over

the past year relating to data collection and reporting, such as the establishment

of the national reporting framework on key indicators of Indigenous disadvantage

(which is discussed more fully in the next section of this chapter).

However, the long-standing commitment of

governments to develop benchmarks and action plans for key areas of Indigenous

disadvantage through the various inter-governmental ministerial councils

remains largely unfulfilled. Accordingly, it is not possible to determine

whether government efforts to address Indigenous disadvantage have progressed

at a rate that meets the expectations (and targets) of governments and

Indigenous peoples. There are no publicly reported goals setting out what

is an acceptable rate of improvement against which we can determine whether

current progress is adequate and fully matches the potential of available

resources and programs. This is a critical issue of lack of accountability

of government and I return to it later in this chapter.

Despite the lack of publicly reported benchmarks

and action plans, we can still evaluate progress in addressing Indigenous

disadvantage from the following three perspectives.

First, we can see whether there have been improvements in

the circumstances of Indigenous peoples on a number of key indicators

over the past five and ten years. Generally, due to difficulties in comparing

data over time periods the Australian Bureau of Statistics recommends

that such comparisons be made on the basis of changes in percentages over

time rather than raw figures.[21]

Second, we can see whether there have been

improvements in the situation of Indigenous peoples compared to non-Indigenous

people over the past five and ten years. In other words, given the prime

goal of the government of eliminating the inequality in socio-economic

conditions experienced by Indigenous peoples, is there relative improvement

in the situation of Indigenous peoples compared to the rest of Australian

society? If the government's approach is working then we can reasonably

expect a continual closing of the gap between the two groups.

Third, we can make comparisons between the

situation of Indigenous peoples in Australia and Indigenous peoples in

other similar countries, as well as to people in less developed countries.

By doing so we can establish whether we are progressing at a rate comparable

to that in other countries or whether we are lagging behind in the improvements

being achieved.

The government's view is that it is making

progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage. In October 2003 the Minister

for Indigenous Affairs stated:

The wellbeing of Indigenous people is improving under

this Government. Record amounts of money and effort are now being spent

on trying to solve the problem of Indigenous disadvantage. Since coming

to Government, real steps forward have been made. Between the 1996 and

2001 censuses, many indicators of Indigenous disadvantage show real

improvement. For example:

- Indigenous unemployment rate fell from 22.7 per cent

to 20.0 per cent, and there were an additional 18,000 Indigenous people

in employment- the proportion of Indigenous people employed in the

private sector rose from 46.3 per cent to 48.5 per cent- the proportion of Indigenous adults who had left school

before their 15th birthday fell from 44.2 per cent to 33.4 per cent,

and- the proportion of Indigenous adults with post school

qualifications rose from 23.6 per cent to 27.9 per cent- the proportion of Indigenous children who stayed on

at school through to Year 12 increased from 29.2 per cent in 1996

to 38 per cent in 2002- there were 5566 Indigenous students enrolled in a bachelor's

level degree or higher degree course in 2002, 24.3 per cent more students

than were enrolled in 1996- there were 59 763 Indigenous people who undertook post-secondary

vocational and educational training in 2002, nearly twice the number

of Indigenous students registered for training in 1996.

While things are getting better, I am not saying

everything is good or that we can sit back and be complacent. This Government

will remain committed to building an Australia where Indigenous people

enjoy the same standards of living as other Australians while maintaining

their unique cultural identities.[22]

In the debate on the Reconciliation

Bill 2001 in November 2003, Senator Ferris also stated the government's

position as follows:

Despite (the opposition's) claims of economic failure

and government policy failure, let us have a look at some of the improvements

that have taken place in Indigenous affairs since this government

came to office in 1996.

In terms of education, from 1996 to 2002 the proportion

of Indigenous children who stayed on at school increased from a very

poor 29.2 per cent to 38 per cent. I know that 38 per cent is still

very low, but an improvement of 10 per cent since this government

came to office is very significant. More importantly, the number of

Indigenous students registered for post-secondary vocational and educational

training has nearly doubled from 1996 to 2002 ... to a total of 59,763...

if that is failure of government policy, one can only imagine what

would be determined to be successful. The number of young Indigenous

Australians who are undertaking post-secondary training has almost

doubled. Over the same period of time, there was a 32 per cent increase

in the number of Indigenous men and women involved in bachelor-level

degree courses or higher degree courses in Australian universities.

I know that those figures are still low, but we are starting to build

a base of economic advantage through higher education and training

for young Indigenous men and women ...

In terms of unemployment, the unemployment rate for

Indigenous people actually fell from 22.7 per cent to 20 per cent

between the 1996 census and the 2001 census. Again, I am the first

to say that we have a long way to go before we can honestly in this

place say that there is equality of opportunity for jobs for young

Indigenous people. However, between 1996 and 2001 the number of Indigenous

people in employment increased from 82,346 to 100,348, an increase

of 22 per cent...

In terms of health, the Australian government has substantially

increased its spending on Indigenous-specific health programs. Such

spending is now at record levels. So much for failure ... Our total spending

on specific Indigenous health services this year will rise to more

than $258 million-more than has ever been spent before. Again I say

that we know this does not indicate we are going to solve this problem,

but it is a significant first step. This is a real increase of nearly

90 per cent since this government took office in 1996... how can you

say that this is a failure of government policy? We have increased

real spending on Indigenous-specific health by more than 90 per cent

since 1996. In the last five years, 46 remote communities have gained

access to primary health care for the very first time. Indigenous

infant and perinatal death rates have fallen by a third over the last

decade...

Commonwealth spending on Indigenous programs

has increased by one-third in real terms since 1996 and is now at record

levels. In 2003-04, the Commonwealth government will spend $2.7 billion

on Aboriginal affairs, on Aboriginal policies-more than has ever been

spent by any government in this nation's history. There is still much

that we can do and still much that state governments can do to help

with the practical measures that improve the day-to-day lives of Indigenous

Australians, but, as we all know, many of those problems will not be

solved with money. You cannot continue to just throw money at the issue

without looking at some of the other measures ...This government is committed to seeing

that every policy initiative is carried out to reconcile Indigenous

Australians and the broader community. Improvements are being made,

and the statistics that I gave to this chamber earlier indicate that.

We are making steps forward. There is a long way to go.[23]

These statements have been reproduced here

at length to ensure that I have authentically represented the government's

position on the rate of progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage.

There are a number of notable features about

these statements. First, the government's position on reconciliation clearly

states that the ultimate test of success is whether the inequality experienced

by Indigenous peoples compared to non-Indigenous people is eliminated.

Despite this, in its claims to success above there is not a single reference

to progress in reducing the gaps that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous

Australians.

The only reference by the Minister to this

inequality gap can be found in a press release dated 12 November 2003,

which comments on the release of the first national report on national

indicators for overcoming Indigenous disadvantage.[24] The Minister stated: 'While there has been improvements in many key indicators,

greater rates of improvement for non-Indigenous people, tend to mask the

gains that have been made.' [25]

In my progress report on reconciliation

in the Social Justice Report 2002, I noted a tendency of the

government to misrepresent progress towards reconciliation through the

way that it presents statistics.[26] This

statement by the Minister is a further example of this. Greater rates

of improvement in key indicators for non-Indigenous Australians do not

'mask the gains that have been made' for Indigenous people. Instead, they

indicate that the gains made have not been sufficient to reduce the level

of inequality or that improvements for Indigenous peoples are not keeping

pace with the rest of society. There is a substantial difference between

presenting information in this way and the way that it has been presented

by the government.

Second, there are significant omissions

in the indicators that the government presents as demonstrating 'real

improvement'. This is most obvious in relation to indicators of health

status, where the only achievement listed above is that the government

has 'substantially increased its spending on Indigenous-specific health

programs to record levels'. There are also no indicators cited relating

to contact with criminal justice processes or care and protection systems,

for example.

At no stage does the government state that

there are areas where the situation is not improving. The Minister's statement

above, for example, is unequivocal that 'the wellbeing of Indigenous people

is improving under this Government'. The only qualification, that there

is still a way to go, also does not admit lack of progress in key areas:

'While things are getting better, I am not saying everything is good or

that we can sit back and be complacent'. It is hardly a frank assessment

of the actual situation.

Third, some of the measures of success are

presented purely as raw numbers and as percentages of increases in raw

numbers (for example, 5566 Indigenous students enrolled in a bachelor's

level degree or higher degree course in 2002, 24.3 per cent more students

than in 1996). As noted above, the ABS cautions against such presentation

of statistics as they do not account for changes in the accuracy of data

collection or increased rates of identification of people as Indigenous.

This can result in the presentation of the level of progress being misleading.

Indeed, as discussed shortly, there are significant concerns being expressed

about poor rates of achievement by the government in education over the

past five years, particularly in relation to higher education.

Taking these factors into account, and examining

the statistics on Indigenous well-being from the different perspectives

listed above (namely, on the basis of absolute change in the situation

of Indigenous peoples; relative change compared to the non-Indigenous

population; and where available, international comparisons), it can be

seen that the claim of the government that 'the wellbeing of Indigenous

people is improving under this Government' cannot be verified across many

core areas of practical reconciliation. There are undoubtedly some areas

where improvements are being realised. Overall, however, there is no consistent

forward trend in improving the well-being of Indigenous peoples, and particularly

no forward trend towards a reduction in the disparity between Indigenous

and non-Indigenous Australians.

Appendix one of this report provides a statistical

profile of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. It includes

information on the current status of Indigenous peoples on key measures

of socio-economic well-being including health status, employment, income,

education, housing, and contact with criminal justice and care and protection

systems. The main findings in the Appendix in terms of progress in addressing

Indigenous disadvantage across these areas are summarised below.

Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantageIncome

Employment

Education

Housing

Contact with criminal justice system

Contact with care and protection system

|

Of particular concern is the lack of achievement in relation

to improving the health status of Indigenous Australians. Appendix One

illustrates the following.

Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage

|

These figures indicate that there are clear

disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and limited

progress in reducing these disparities across many key areas of socio-economic

status.

These findings are confirmed by significant

research published by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research

(CAEPR) in late 2003. CAEPR released analysis by Professor Jon Altman

and Dr Boyd Hunter of 2001 Census data which sought to monitor progress

towards reconciliation by measuring absolute and relative changes in Indigenous

peoples' labour force status, income, housing, education and health over

the period 1991-2001.

As the authors of the study noted, for the

first time ever there was a relatively close correlation between the conduct

of the five-yearly national census and political cycles:

The change in government shortly before the 1996 Census

means that the 1996 data reflect the Labor legacy rather than the

effect of early policy initiatives of the new government. While arguably

there are various types of policy lags ... the second inter-censal period

(1996-2001) can be readily interpreted as the policy domain (and legacy)

of the Howard government. [27]

The research aimed to answer the following question:

How do the outcomes in the period 1991-1996, represented

by the Federal government and many conservative commentators as a

period when symbolic reconciliation was too dominant, compare with

those in the period 1996-2001 when a change in government saw greater

policy focus on practical reconciliation? [28]

The research concluded that in the period

1996-2001, labour force status for Indigenous people worsened relative

to the rest of the population when measured by labour force participation

rates, unemployment rates, the employment to population ratio, and rate

of full time employment. There was, however, a slight improvement in employment

of Indigenous people in the private sector. The authors expressed concern

about this general worsening in Indigenous labour force status as it moved

'against the trend for the rest of the population'.[29] They noted:

Unemployment rates fell by less for the Indigenous population

than for other Australians, despite rapid economic growth over the

five year period and growth in numbers participating in the CDEP scheme.

There is little evidence of trickle down improving Indigenous economic

participation and reducing the significance of non-employment (welfare)

income. Given that low skilled workers are often the first to lose

work in an economic downturn, the lack of improvement is worrying,

especially if there is any significant deterioration in the Australian

and international economies in the near future. [30]

In terms of income, the research noted a

continued relative decline in income for Indigenous individuals, but a

slight improvement in the relativity in median family income between Indigenous

and non-Indigenous families. [31] In terms

of housing, the research also noted marginal improvements in the relativity

between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people for both home ownership rates

and household size.

The research expressed significant concern

about the lack of improvement in relation to both health and education.

The authors expressed concern at the 'substantial inertia in Indigenous

health'[32] as indicated in the lack of improvement

in relativities relating to life expectancy and proportion of the population

aged over 55 years. In relation to education, the research notes a slight

reduction in the disparity in the proportion of adults who have never

gone to school, but a worsening in the comparative rate of early school

leavers. There was a slight improvement in the proportion of Indigenous

adults with post-school qualifications, but a significant decline in the

comparative rate of Indigenous youth currently attending a tertiary institution.

The authors commented that:

it is an indictment of current education policy that

there was a large decline in the Indigenous to non-Indigenous ratio

between 1996 and 2001 ... future prospects for improved socio-economic

outcomes for the Indigenous population are not good when attendance

of Indigenous youth at tertiary institutions fell by 2.2 percentage

points ... Even in its own terms the government is failing in the education

arena. [33]

When these results are compared to the results

achieved by the previous government in the period from 1991-1996, the

research revealed that:

in absolute terms, it is difficult to differentiate

the performance of governments pre-1996 and post-1996. However, in relative

terms - that is when comparing the relative wellbeing of Indigenous

people as a whole with all other Australians - there is some disparity

between the periods, with the early period 1991-1996 clearly outperforming

the more recent period ...[34] Of particular

concern was relative decline over the period in educational and health

status. [35]

As a consequence, the authors offered the

following appraisal of the achievements of practical reconciliation in

addressing Indigenous disadvantage:

Despite the policy rhetoric of three Howard governments,

there is no statistical evidence that their policies and programs are

delivering better outcomes for Indigenous Australians, at the national

level, than those of their political predecessors ...[36] It is of particular concern that some of the relative gains made between

1991 and 1996 appear to have been offset by the relative poor performance

of Indigenous outcomes between 1996 and 2001[37] ...

This intractability is worrying in part because it is evident during

a time when (in) Australia the macro-economy is growing rapidly. This

suggests, in turn, that problems are deeply entrenched - it is not just

a matter of choosing between practical and symbolic reconciliation. [38]

There is one further issue of grave concern

relating to progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage. As CAEPR note:

A major problem for both Indigenous Australians and

the nation is that other research suggests that the situation described

using the latest 2001 Census statistics is likely to get worse, rather

than better, over the next decade. [39]

This is due to the demographic characteristics

of the Indigenous population. As I noted in the Social Justice Report

2002, there is 'a well-documented, emerging crisis facing Indigenous

policy design'. Not only is the Indigenous population growing at a faster

rate than the non-Indigenous population (2.3 per cent compared to 1.2

per cent annually), but the Indigenous population's median age is younger

(20 years compared to 35 years) and nearly twice as many Indigenous compared

to non-Indigenous people are under 15 years of age (almost 40 per cent

compared to just over 20 per cent). Similarly, only 2.8% of the Indigenous

population are aged over 65 compared to 12.5% of the non-Indigenous population. [40] The consequence of this age structure

and rate of population growth is that there will be a significant increase

in the number of Indigenous people entering the age group where they will

be seeking employment.

Based in this demographic profile, research

by CAEPR forecasts that there will be a further widening of the disparity

between Indigenous and non-Indigenous employment rates over the next decade:

Because the rate of employment growth is anticipated

to be slower than population growth, the overall employment rate is

expected to fall from 40 per cent to 36 per cent over the projection

period (2001-2011). Assuming no change in the labour force participation

rate, the reverse side of this equation will see unemployment numbers

rise from an estimated 32,808 in 2001 to 58,565 by 2011, with a consequent

increase in the unemployment rate from 22.5% to almost 31% of those

in the labour force.

These projections point clearly to a worsening in the

labour force status of Indigenous adults. Moreover it should be noted

that they are based on the inclusion of working CDEP scheme participants

in the estimates of persons employed. If these were excluded, and

instead counted as unemployed ... then predicted labour market outcomes

for Indigenous people would become far worse, with an unemployment

rate of 43 per cent rising to 50 per cent... [41]

It is worth recalling that the equivalent rates for

the rest of the Australian population are presently around 6.0 per

cent for unemployment ... these are likely to remain relatively unchanged ...

The medium term prognosis, then, all other things being equal, is

for a substantial worsening of the overall labour force status of

Indigenous people both relatively and absolutely. [42]

These figures from CAEPR update analysis

that they conducted in 1997 and 1998 into the likely growth in employment

disparity for Indigenous peoples. [43] Consequently,

the government has been aware of the likelihood of deterioration in employment

status for Indigenous peoples since at least 1997. The absence of benchmarks

and an action plan to address this potential situation is a serious omission

from the 'practical reconciliation' agenda.

These projected high rates of Indigenous

unemployment and low rates of Indigenous participation in the labour force

have impacts not only on the overall financial wellbeing of Indigenous

individuals and communities, but it also has major direct impacts on the

Australian economy at large. For example, CAEPR estimates the cost of

the current level of Indigenous employment (including unemployment, underemployment,

CDEP participation and discouraged workers) to be approximately $700 million

in total foregone tax revenue. [44] CAEPR

have made the following projections for the situation over the decade

to 2011:

If Indigenous unemployment was reduced to a level commensurate

with the rest of the population, and assuming that this latter rate

remained constant, then the savings to government in payments to the

unemployed, in real terms, would be $328 million in 2006 and $450

million in 2011. On the credit side, if all those formerly unemployed

were to gain mainstream employment (excluding CDEP scheme employees)

with an annual income equivalent ... [similar to reported income of non-CDEP

employees in 1994] ... then the estimated tax return to government would

approximate $211 million and $290 million in 2006 and 2011 respectively.

These estimates are conservative because they hold the

Indigenous participation rate at their 2001 levels. If all the Indigenous

people outside the labour force who wanted jobs found them, then the

government would save an additional $416 million in 2006 and $472

million in 2011 on government payments. That is, the additional welfare

cost of not finding work for discouraged workers is even greater than

that for the unemployed. The cost of lost tax revenue from discouraged

workers will be as much as $345 million by 2011. [45]

CAEPR have summarised this situation as

follows: 'the current fiscal cost of this failure to eradicate Indigenous

employment disparity is massive - in 2001, it was estimated to be around

0.5 per cent of Australian GDP. Findings from this new analysis indicate

that the cost will be even higher in the future.' [46]

Overall, the statistics across key areas

of Indigenous disadvantage for the past five years indicate that there

is no consistent forward trend in reducing the extent of disadvantage

experienced by Indigenous peoples, and limited progress in eradicating

the disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. There

is some evidence that in relation to key measures, this situation may

deteriorate further in the coming decade. The outcomes being achieved

by governments are not adequate on any measure of success and despite

the investment of significant resources by governments. This situation

needs to change.

c) Implementing the commitments of the Council of Australian

Governments

An area where there has been significant

progress in advancing the reconciliation process over the past year is

the efforts of governments, lead by the federal government, in implementing

the commitments made by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) towards

reconciliation.

In its communique of 3 November 2000, COAG

agreed to take a leading role in driving change to address Indigenous

disadvantage. COAG agreed to focus on three priority areas: community

leadership; reviewing and re-engineering programs and services to support

families, children and young people; and forging links between the business

sector and indigenous communities to promote economic independence. As

part of this process, Ministerial Councils were to develop 'action plans,

performance reporting strategies and benchmarks' with COAG to review progress

regularly.

In its communique of 5 April 2002, COAG

agreed to conduct a number of whole-of-government community trials across

Australia and to commission an annual reporting framework on key indicators

of Indigenous disadvantage. This reporting framework had its genesis in

the efforts of the Ministerial Council on Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Affairs in progressing COAG's communique of November 2000.

This section reviews developments in relation

to the disadvantage reporting framework, COAG trials and Ministerial action

plans over 2003.

i) Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage - Annual

report against key indicators

In his capacity as Chairman of COAG, the

Prime Minister wrote to the Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State

Service Provision[47] on 3 May 2002 to request

the Committee to develop a framework for reporting to COAG against key

indicators of indigenous disadvantage. COAG had agreed to the production

of such a regular report at its April 2002 meeting.

The Steering Committee developed a draft

reporting framework in 2002 and consulted with Indigenous organisations

and governments about it in 2002 and 2003. This draft framework was the

subject of a workshop convened by the Social Justice Commissioner in November

2002, and was discussed in detail in Chapter 4 of the Social Justice

Report 2002.

On 22 August 2003, the Prime Minister wrote

to the Steering Committee on behalf of COAG to formally endorse the Committee's

proposed framework for reporting progress in addressing indigenous disadvantage.

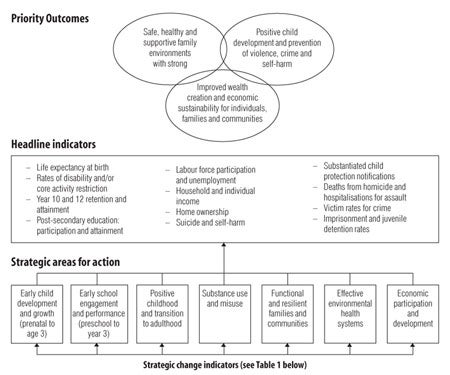

The finalised framework is reproduced in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 - COAG Framework for reporting on Indigenous

disadvantage

Click

here to view a larger version of this figure.

COAG and the Prime Minister nominated two

core objectives for the Report: namely, to identify indicators that 'are

of relevance to all governments and indigenous stakeholders' and 'demonstrate

the impact of programme and policy interventions'. [48]

As the Chair of the Steering Committee has stated about

the report:

The ... commissioning (of this report by COAG) demonstrates

a new resolve, at the highest political level, not only to tackle

the root causes of Indigenous disadvantage, but also to monitor the

outcomes in a systematic way that crosses jurisdictional and portfolio

boundaries. In doing so, the Report will henceforth also raise the

transparency of government's performance.

This report's purpose, therefore, is to be more than

just another collection of data. It seeks to document outcomes for

Indigenous people within a framework that has both an agreed vision of what life should be for Indigenous people and a strategic focus on key areas that need to be targeted if that longer term vision is

to be realised. [49]

The vision of the reporting framework

is that 'Indigenous people will one day enjoy the same overall standard

of living as other Australians. They will be as healthy, live as long,

and participate fully in the social and economic life of the nation.' [50] This vision is encapsulated in the three,

inter-related priority outcomes of the reporting framework, namely:

- Safe, healthy and supportive family environments with

strong communities and cultural identity; - Positive child development and prevention of violence,

crime and self-harm; - Improved wealth creation and economic sustainability

for individuals, families and communities. [51]

The report also seeks to present the statistics

within a strategic framework. There are two key features to this

framework. First, it seeks to report on Indigenous disadvantage on a holistic

and whole-of-government basis. As the Committee has explained:

[T]he report is predicated on the view that achieving

improvements in the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians in a particular

area will generally require the involvement of more than one government

agency, and that improvements will need preventative policy actions

on a whole-of-government basis ...[52]

Without detracting from the importance of individual

agencies being responsible and accountable for the services they deliver,

the structure of this Report seeks to facilitate interaction between

sectors and between governments on programs that are delivered to Indigenous

people. Furthermore, it can assist agencies to consider how they can

strategically develop programs which have the capacity to deliver outcomes

outside of their traditional sphere of action. [53]

A recurring theme of the framework is acknowledgement

that areas such as health, education, employment, housing, crime and so

on are inextricably linked. Disadvantage or involvement in any of these

areas can have serious impacts on other areas of well-being. Acknowledgement

of, and action based on, these interconnections is therefore critical

in assisting COAG to inform policy development with respect to Indigenous

peoples.

Second, the framework is premised on a realisation

that there are a range of causative factors for Indigenous disadvantage.

This necessitates reporting on progress in addressing both the larger,

cumulative indicators (such as life expectancy, unemployment and contact

with criminal justice processes) which reflect the consequences of a number

of contributing factors, as well as identifying progress in improving

these smaller, more individualised factors.

To reflect these strategic considerations,

the framework seeks to present progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage

at two levels. The first level is a series of twelve 'headline indicators'

that provide a snapshot of the overall state of Indigenous disadvantage.

The twelve indicators are:

- Life expectancy at birth;

- Rates of disability and/or core activity restriction;

- Years 10 and 12 retention and attainment;

- Labour force participation and unemployment;

- Household and individual income;

- Home ownership;

- Suicide and self-harm;

- Substantiated child protection notifications;

- Deaths from homicide and hospitalisations for assault;

- Victim rates for crime; and

- Imprisonment and juvenile detention rates.

These 'headline indicators' are measures

of the major social and economic factors that need to be improved if COAG's

vision of an improved standard of living for Indigenous peoples is to

become reality. But as the Chairman of the Steering Committee notes, these

headline indicators:

reflect desired longer term outcomes and therefore

are themselves only likely to change gradually. Because most of the

measures are at such a high level and have long lead times (eg life

expectancy) they do not provide a sufficient focus for policy action

and are only blunt indicators of policy performance.

Indeed, reporting at the 'headline' level alone can

make the policy challenges appear overwhelming. The problems observed

at this level are generally the end result of a chain of contributing

factors, some of which may be of long standing. These causal factors

almost never fall neatly within the purview of a single agency of government,

or indeed a single government. [54]

Hence, the Steering Committee has devised

a second level of reporting which breaks down these broader, longer term

measures. The Committee has identified seven 'strategic areas for action'

and a number of supporting 'strategic change indicators' to measure progress

in these. The particular areas and change indicators have been chosen

for their 'potential to respond to policy action within the shorter term ...

(and to indicate) intermediate measures of progress'[55] while also having the potential in the longer term to contribute to improvements

in overall Indigenous disadvantage (as reflected through the 'headline

indicators'). [56] The seven strategic areas

and related indicators are set out in the following table.

Table 1: COAG Overcoming Disadvantage framework:

Strategic areas for action and strategic change indicators[57]

| Strategic areas for action | Strategic change indicators |

| 1. Early child development and growth (prenatal to age 3) |

|

| 2. Early school engagement and performance (preschool to year 3) |

|

| 3. Positive childhood and transition to adulthood |

|

| 4. Substance use and misuse |

|

| 5. Functional and resilient families and communities |

|

| 6. Effective environmental health systems |

|

| 7. Economic participation and development |

|

The Steering Committee published its first

report against this framework, titled Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage

- Key Indicators 2003, in November 2003. The report confirms that

Indigenous disadvantage is broadly based, with major disparities between

Indigenous and other Australian in most areas. As the Chairman of the

Steering Committee has commented on the findings of the report:

[The report] confirms the pervasiveness of Indigenous

disadvantage. It is distressingly apparent that many years of policy

effort have not delivered desired outcomes; indeed in some important

respects the circumstances of Indigenous people appear to have deteriorated

or regressed. Worse than that, outcomes in the strategic areas identified

as critical to overcoming disadvantage in the long term remain well

short of what is needed. [58]

The presentation of information within the

strategic areas also highlights the inter-related nature of the challenges

faced in improving Indigenous well-being. As the Chairman of the Committee

notes, 'in the three strategic areas that focus on young Indigenous people,

the potential for cumulative disadvantage is plain to see.' [59] The presentation of what are generally well known statistics in this way

under the strategic areas of action 'are not rocket science'[60] but the ability to highlight cumulative disadvantage factors is a significant

breakthrough which should assist policy making in relation to Indigenous

peoples.

There are, however, two main issues relating

to the framework which have a bearing on how influential it will be in

promoting change to policy and program approaches by governments and ultimately

in improving the well-being of Indigenous peoples.

First, a critical issue for the reporting

framework is the availability of adequate and regular data. The Social

Justice Report 2000 identified limitations in data collection as

a critical problem that must be addressed in order to ensure government

accountability for progress towards reconciliation. [61] This has been an issue that the Steering Committee has had to grapple

with in establishing the framework and in reporting against it.

The Committee has noted that the existence

of data sets or ease of developing them was a practical consideration

that influenced the choice of indicators in the framework:

In many cases, the selected indicators are a compromise,

due not only to the absence of data, but also to the unlikelihood of

any data becoming available in the foreseeable future ... In some cases,

however, an indicator has been included even when the data are not available

on a national basis, or are substantially qualified. These are indicators

where there is some likelihood that data quality and availability will

improve over time. In two cases where there were no reliable data available,

the indicators were nevertheless considered to be so important that

qualitative indicators have been included in the report. [62]

In reporting against each of the headline

indicators and strategic change indicators in the first report, the Steering

Committee has noted limitations in data availability and quality. Each

chapter of the report contains a section titled 'future directions in

data' which notes current developments which will contribute to addressing

the difficulties in data availability and quality in future years, and

how exactly specific initiatives will do this. It also identifies major

deficiencies and areas where there is an urgent and outstanding need for

improved statistical collection methods. [63]

I envisage that in future years the Committee

is also going to face additional issues relating to the regularity of

data availability and hence the ability to report progress over time.

In this regard, I have previously recommended that the Indigenous General

Social Survey (IGSS) should be conducted on a triennial basis, alongside

the General Social Survey, to ensure the regularity of comparable data

on the unique issues covered in that survey. Currently, the IGSS is intended

to occur every 6 years, with the results of the first IGSS conducted in

2002 due to be released in early 2004.

On the positive side, it was announced in

the federal budget for 2003 that a national longitudinal study on Indigenous

children will be conducted. This study will track the development of 4,000

Indigenous children over a nine year period and will be a rich source

of ongoing data for the Steering Committee. The study, however, is not

due to commence until at least 2005 in order for extensive consultations

to be conducted with Indigenous peoples and communities prior to its introduction.

There may also be issues in future years

relating to the ability to disaggregate available data from the national

and state or territory level, down to a regional level.

It is critical that the recommendations

and suggestions of the Steering Committee in relation to improved data

collection are addressed as a matter of urgency in order to ensure that

the reporting framework is able to fully realise its potential and to

be viable into the longer term. As the Chairman of the Steering Committee

notes:

[the] immediate contribution [of the report] is constrained

by serious gaps and deficiencies in data. For example, we know that

hearing impediments in young children can seriously undermine their

ability to succeed at school, yet we have little basis for knowing whether

this problem is getting better or worse. We know that attendance at

school is critical to lifelong achievement, but we have inadequate data

to monitor it. Substance abuse is blighting young lives, but we have

little systematic information on it. Data on the extent of disabilities

among Indigenous people is almost non-existent. The Review documents

these and a range of other data priorities that will need to be addressed

if the Report is to realise its potential and meet COAG's needs. [64]

In producing this report I am mandated to

make recommendations on actions which should be taken to secure the enjoyment

and exercise of the rights of Indigenous peoples. In light of the crucial

nature of this issue, I have chosen to make the following recommendation

about improving data collection in the context of the Steering Committee's

report.

Recommendation 1 on reconciliation: Data

|

The second main issue that impacts on the

potential of the Steering Committee's report is how it is incorporated

into policy design and programmes across governments and between government

departments. As the Chairman of the Steering Committee notes:

The Report's contribution to this important national

endeavour is essentially informational. It does not (and

cannot) in itself provide policy answers. But it can (and hopefully

will) help governments and Indigenous people to identify where programs

need to deliver results, and to assess whether they are succeeding.

For it to be effective in this, it will be important that governments

integrate elements of the reporting framework into their policy development

and evaluation processes. [65]

This is the most critical issue relating

to the report - ultimately it does not matter how refined the statistics

that are reported are if the report is not utilised by governments to

inform and change the way they go about delivering services to Indigenous

peoples.

In the Social Justice Report 2002, I expressed the concern that the Steering Committee's framework 'currently

exists in isolation from any other form of performance monitoring, particularly

on identifying progress on important goals such as capacity building and

governance reform, as well as identifying the unmet need and accordingly

whether policy approaches are moving forward or in fact regressing.' [66] If the reporting framework is not integrated into policy development then

the Steering Committee's report risks becoming, in the words of the Chairman

of the Steering Committee, 'an annual misery index'[67] which simply reminds us on an annual basis of continuing Indigenous disadvantage

without action to change this situation.

At this stage, it is not clear how the report

will inform policy development and how governments will use the report

to review their approach to Indigenous issues. This is in part because

COAG has not yet formally considered and responded to the first report

of the Steering Committee. It is anticipated that further guidance will

be provided when COAG next meets.

It is clear, however, that the other two

main activities of COAG relating to reconciliation have a vital role to

play in drawing lessons from the reporting framework and connecting the

framework to day to day policy development processes. As the Chairman

of the Steering Committee has noted:

One important national vehicle for this is the Action

Plans that are being developed by Ministerial Councils in such areas

as health, education, employment, justice and small business. The

whole-of-government, outcomes orientation of the framework also complements

the coordinated service delivery trials in eight different regions

across Australia that was initiated by COAG. [68]

It is notable that when developing the framework

for reporting it was debated whether there should be a third level of

indicators added to the framework which could report on service delivery.

Ultimately, this was seen as a role for the Ministerial Council action

plans, which are intended to link service delivery with the reporting

framework. These action plans form the vital link in drawing lessons from

the reporting framework. Progress in developing these action plans is

discussed in the next section of this report.

Overall, as I noted in the Social Justice

Report 2002, the Steering Committee's framework is a 'significant

institutional development in measuring progress for Indigenous peoples'

and the 'only positive form of monitoring and evaluation that the Government

has provided for practical reconciliation'.[69]

The endorsement of the framework by COAG

in August 2003 and the production of the first report by the Steering

Committee in November 2003 are both substantial achievements. And as the

Chairman of the Steering Committee has stated, one of the most significant

contributions of the reporting framework is that it 'challenges us to

do better. It also vindicates COAG's decision to give new impetus to the

development and coordination of Indigenous policies and programs.' [70]

ii) Developing Ministerial Council action plans

and benchmarks

The COAG Communique on reconciliation of

3 November 2000 commits to an integrated framework for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage. As the former Minister for Immigration and Multicultural

and Indigenous Affairs notes:

Under the aegis of the Framework to Advance Reconciliation

agreed by the Council of Australian Government s(COAG) in November

2000, all Australian governments are collectively establishing a comprehensive

regime of performance monitoring and reporting that supports (the

government's) overarching performance benchmark and objective of...

a society where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples enjoy

comparable standards of social and economic wellbeing to those of

the wider community, especially in the areas of education, health,

employment, and law and justice, while maintaining their unique cultural

identities ...This regime has two key elements:

- regular national report on Indigenous disadvantage;

and- a series of sectoral performance monitoring strategies

and benchmarks oversighted by the responsible Commonwealth/State Ministerial

Council.The purpose of this regime is to enable

governments, community organisations, indigenous people and other Australians

to monitor progress of the nation in overcoming Indigenous disadvantage.

The regime is still in its development phase and the government anticipates

that it will be firmly in place by the third quarter in 2003. [71]

Each Ministerial Council is to develop action

plans, performance reporting strategies and benchmarks for addressing

Indigenous disadvantage. In its action plan, the Ministerial Council on

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs (MCATSIA) resolved to review

all of the other Ministerial Council action plans, performance reporting

strategies and benchmarks in order to identify gaps to COAG and comment

on those gaps. [72] Progress under the action

plans would then be regularly reviewed by COAG.

The COAG communique of 5 April 2002 admits

that progress by the Ministerial Councils in developing action plans and

benchmarks in the year and a half after this commitment was made has been

'slower than expected'.[73] The communique

indicates that COAG will continue to review progress and that a report

on the state of the action plans would be submitted by MCATSIA to COAG

for consideration no later than the end of 2003.

In his submission to the Senate Legal and

Constitutional References Committee inquiry into national progress towards

reconciliation, the Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous

Affairs noted that MCATSIA had provided its initial report of comments

on the action plans to the Prime Minister (in his role as the Chair of

COAG) in June 2003. [74] At the time of writing,

MCATSIA's report had not been made public and a number of action plans

were still not finalised. It has now been three years since COAG agreed

to the production of these action plans and benchmarks.

The federal government noted in November

2002 that:

Already a number of Ministerial Councils have performance

monitoring strategies and benchmarks in place. A leading example is

the annual performance report against the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander health indicators. Other ministerial councils also have specific

data agreements that will support the development of performance monitoring

strategies and benchmarks. [75]

The government noted that the following

Ministerial Councils have, or had prior to COAG's decision in 2000, developed

action plans:

- Community Services Ministers Conference;

- Ministerial Council on Mineral and Petroleum Resources;

- Australian Transport Council;

- Sport and Recreation Ministerial Council;

- Standing Committee of Attorneys-General;

- The Online Council;

- Primary Industries Ministerial Council;

- Ministerial Council for Education, Employment, Training

and Youth Affairs; - Australian Health Ministers Conference;

- Cultural Ministers Conference;

- Housing Ministers Conference; and

- Small Business Ministerial Council. [76]

Examples of Ministerial Council action plans,

performance reporting strategies and benchmarks include the following:

Community services and juvenile

justice: The central aspect of the community services

action plan is the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community

Services Information Plan. This implements the report Principles

and Standards for Community Services Indigenous Population Data and aims to improve data collection across this sector, with a key focus

on child protection and welfare, juvenile justice, the Supported Accommodation

Assistance Scheme and agencies funded under the Commonwealth / State

Disability Agreement.Housing: In

2001, state and territory Housing Ministers and relevant federal Ministers

committed to new directions in housing through Building a better

future: Indigenous Housing to 2010.[77] An agreement on national housing information was also signed by all

jurisdictions in 1999. All jurisdictions have agreed to a performance

monitoring system through improving the availability of reliable data;

developing reporting systems which will enable performance appraisal

at the national, state / territory and regional levels; and reporting

annually to relevant ministers at the federal and state/territory level

against outcomes identified in Building a better future. A

reporting framework has also been developed by ATSIC and the Department

of Family and Community Services to facilitate this performance reporting.Employment: Indigenous specific employment data is collected at the federal level.

Quarterly reports of outcomes data are published by the Department of

Workplace Relations.Justice related areas: The Standing Committee of Attorneys-General have agreed to performance

indicators in five areas, namely prevent crime and community safety;

improve access to justice related services; improved access to bail;

improved access to diversionary schemes; and enhanced participation

of Indigenous peoples in justice administration systems.Health: Processes

have been in place since 1998 for reporting on national performance

indicators, although 'data required to report on some indicators are

either unavailable, of poor quality, or require substantial development'.[78] Indigenous health care agreements with the states and the Commonwealth/State

Australian Health Care Agreements also have requirements relating to

data collection. The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Health was endorsed by health ministers

in July 2003. It includes reporting on three 'key result areas' which

relate largely to reforming the structure of the health system to increase

its accessibility to Indigenous people.Education: The

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs

(MCEETYA) has agreed on national performance indicators for all students

(not just Indigenous). The main measures are national literacy and numeracy

benchmarks for years 3 and 5 (with benchmarks for year 7 still under

development). The objective is that all students meet the standards.

Under the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy

(NATSIEP), all governments have made commitments 'to bring about equity

in education for Indigenous Australians'.[79] The main goals of the policy are improved Indigenous participation in

educational decision-making; equality of access to education services;

equity of educational participation; and equitable and appropriate educational

outcomes. These goals are enshrined in the Indigenous Education

(Targeted Assistance) Act 2000 (Cth).One of the main federal programs under the NATSEIP

is the Indigenous Education Strategic Initiatives Programme (IESIP).

IESIP funding is provided on a quadrennial basis and States/Territories

are required to acquit the spending of IESIP funds against negotiated

indicators which include numeracy and literacy, Indigenous workforce,

retention rates and attrition. Service providers are required to submit

annual reports against annual targets. This information is tabled,

along with progress in addressing other performance indicators, in

Parliament through the National Report to Parliament on Indigenous

Education and Training by the federal Department of Education

Science and Training. The first report was tabled in 2002. Programs

under the IESIP, such as the National Indigenous English Literacy

and Numeracy Strategy, also have targets for improving literacy and

numeracy rates of Indigenous people to levels comparable to other

Australians. [80]

The federal government admits that these

action plans 'vary in their sophistication'.[81] In fact, many of these action plans are rudimentary in scope and deal

almost exclusively with data collection and performance monitoring issues.

Very few have any benchmarks or targets.

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation

defined a 'benchmark' as 'an agreed standard or target that reflects the

community aspirations that either have been met or are desirable to be

met'.[82]

Benchmarking is a critical aspect of ensuring

human rights compliance and accountability. This is in accordance with

the guiding principle of 'progressive realisation' under international

human rights law (and as reflected in the International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). The Office of the High Commissioner