Native Title Report 2006: Chapter 2: Economic Development Reforms on Indigenous land

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Native Title Report 2006

Chapter 2: Economic Development Reforms on Indigenous

land

Chapter 1 << Chapter 2 >> Chapter 3

- Introduction

- The government policy framework

- Indigenous land tenures

- 99 Year headleases over Indigenous townships

- Use of the Aboriginal Benefits Account to pay for Government 99 year headleases

- Modifications to the permit system

- Discontinuation of funding and services to homelands

- Shire councils to replace Indigenous community councils

- Housing and home ownership

- Indigenous employment

- Programs supporting Indigenous enterprise and economic development

- Agreements and economic development

- Assessment of the self-access model for Indigenous economic development

- Conclusion

- Findings

- Recommendations

- Introduction to the case studies

Introduction

In 2006 the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet made a

revealing statement about Indigenous affairs. He argued that his own

government’s policy performance in the Indigenous portfolio had been a

failure. He went further to say that while well intentioned, the policies and

approaches of the past 30 years had contributed to poor outcomes for Indigenous

people.

I am aware that for some 15 years as a public administrator too much of what

I have done on behalf of government for the very best of motives has had the

very worst of outcomes. I and hundreds of my well-intentioned colleagues, both

black and white, have contributed to the current unacceptable state of affairs,

at first unwittingly and then, too often, silently and

despairingly.[1]

This statement was made in the context of the Australian Government’s

ambitious reform agenda aimed at significantly recasting Indigenous policy in

remote Indigenous Australia. During 2005 and 2006 the Government implemented

legislative and policy reforms that will change the face of Indigenous

communities located on communally titled land. The Government argued that

communal tenures prevent Indigenous people from improving material wealth and

economic circumstances. According to the Government, individual property rights

will allow Indigenous Australians to accumulate assets and participate in market

economies. The Government’s reforms are designed to emphasise the

individual as an agent in economic self development through ‘building

wealth, employment and an entrepreneurial

culture.’[2] According to the

Minister for Indigenous Affairs:

It is individual property rights that drive economic development. The days of

the failed collective system are

over.[3]

This Chapter will focus on the Government’s

economic reform agenda with discussion about the following:

- individualising title on Indigenous communal lands through 99 year

headleases; - liberalising public access to Indigenous land through the modification of

the permit system; - home ownership on Indigenous lands;

- centralising government services in large Indigenous townships;

- developing regional shire councils to replace Indigenous community

councils - employment and CDEP; and

- access to capital for Indigenous economic and enterprise development.

The government policy framework

The Australian Government’s policy agenda is

contained in the 2006 Blueprint for Action in Indigenous Affairs(hereon referred to as the Blueprint). The

Blueprint defines the Government’s intention to replace protectionist,

welfare-based approaches to Indigenous affairs with market-based approaches to

land, housing, enterprise development and employment. This means opening up

Indigenous land to the wider Australian public and creating more interaction

between remote communities and the Australian economy. The discourse that

accompanies the Government’s policy reforms defines a need to

‘normalise’ Indigenous communities through mainstreaming service

delivery and creating market economies.

We will need to remove barriers to economic opportunity. But we are not

proposing to use government programs to create artificial economies. It

doesn’t work. We are talking about creating an environment for the sort of

employment and business opportunities that exist in other Australian

towns...Land tenure changes will be progressively introduced, subject to the

agreement of traditional owners, to allow for home ownership and the normal

economic activity you would expect in other Australian towns.In places like Wadeye, Cape York and Groote Eylandt this is just beginning to

happen. We want to get to the point where people living in these remote

communities are not solely dependant on community or public housing. They should

be able to buy their own homes. Those who don’t should make a fairer

contribution in rent.[4]

In 2005 the Australian Government announcedlegislative amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern

Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (hereon referred to as ALRA). One significant

addition to the ALRA was a provision that permitted Governments to negotiate 99

year headleases over Northern Territory townships under Indigenous communal land

rights tenure. The headleases would then be divided into sub leases for

individual tenants, home purchasers, businesses and government service

providers.

Accompanying the tenure reforms in 2006 were proposed

changes to the ALRA permit system. The ALRA permit system currently requires all

visitors, non Indigenous residents and non residents to obtain a permit to enter

and stay on Indigenous land. The Australian Government’s aim in reforming

the permit system is to liberalise land access so that the providers of goods

and services can enter Indigenous land without restriction.

Integral to the government’s

‘normalisation’ strategy are proposed changes to the Indigenous

housing system and housing markets. The intention is to increase home ownership

and reduce reliance on government subsidised rental accommodation. According to

the Government, these reforms are dependent on 99 year leases. The Minister for

Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs has determined that

funding for home ownership schemes will be contingent on the states and

territories amending their land rights legislation to make provision for 99 year

headleases.

Finally, the Blueprint sets out the Australian

Government’s intention to limit the supply of services and financial

support to small ‘unsustainable’ Indigenous communities. If

Indigenous people on homelands and outstations want to access health and

education services they will have to move to the larger townships.

The precursor to the Blueprint is the 2003 Council of Australian Governments

report, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage, Key Indicators (The COAG

Report). The Report is the framework on which the Indigenous reform agenda has

been developed. The COAG Report has a dual focus. It maps the extent of

Indigenous disadvantage using 2001 census data and it provides a framework for

the focus of government action. ‘Economic participation’ is the apex

of the tripartite COAG framework, along with creating healthy families and early

childhood. The COAG Report recommends: ‘improved wealth creation and

economic sustainability for individuals, families and

communities.’[5]

A key finding of the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Key

Indicators

2003 Report is that economic development is central to improving the

well-being of Indigenous Australians.A strategic goal of the Australian Government’s Indigenous policy is to

increase Indigenous economic independence, through reducing dependency on

passive welfare and stimulating employment and economic development

opportunities for Indigenous individuals, families and communities.

The COAG Report aims to implement ‘economic participation and

development’ through seven specific areas for action. These are contained

in the COAG strategic areas for action and include the following:

- employment (full-time/part-time) by sector (public/private), industry

and occupation; - CDEP participation

- long term unemployment;

- self employment;

- Indigenous owned or controlled land;

- accredited training in leadership, finance or management; and

- case studies in governance

arrangements.[6]

The COAG Reports on Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage will

be issued on a two yearly basis and will be formulated from a range of data

sources including the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare and the Productivity Commission as well as

government departments. Successive Reports will be used to evaluate the reform

agenda.

Progress will be monitored through the Overcoming Indigenous

Disadvantage reports, which measures key indicators in Indigenous social and

economic well-being from a whole-of-government perspective. In particular, the

increased participation of Indigenous Australians in employment and increased

wealth of Indigenous Australians—collective and individual—will be

monitored. In addition, improvements will be continually monitored through

agencies measuring their contributions against each initiative in the

strategy.[7]

Indigenous land tenures

The Australian Government’s reforms must be considered with full

knowledge of the location, infrastructure, and legislative parameters of

communally titled Indigenous land. As of June 2006, Indigenous Australians held

communal rights and interests to land encompassing almost 23 percent of the

Australian land mass.[8] While there

is no doubt that the Indigenous ‘estate’ is now considerable, most

of the land that has been returned to Indigenous people since the 1970s is

remote, inhospitable and marginal. The process of colonisation over two

centuries ensured that the best land was granted, taken or purchased by

non-Indigenous Australians. The Crown land that was still unallocated by the

1970s remained so for good reason. However, in recent times some of the remote,

coastal land under Indigenous tenure has become attractive to developers,

governments and non-Indigenous residents. This trend is likely to continue as

residential markets spread along the Australian coastline. Land in the central

desert belt of Australia is unlikely to attract residential markets, now or into

the future.

There are three ways that Indigenous land has been returned to Indigenous

people. It has been allocated by governments through statutory land rights,

claimed under the native title regime, or purchased on behalf of Indigenous

people with funds established to provide land to the dispossessed. Indigenous

Australians have also purchased land as individuals, in the same way as

non-Indigenous Australians and through land councils in some states. Land that

has been returned to Indigenous Australians is largely unallocated Crown land.

The majority of the land is located in very remote desert regions with limited

or no infrastructure, roads or utilities.

Native Title

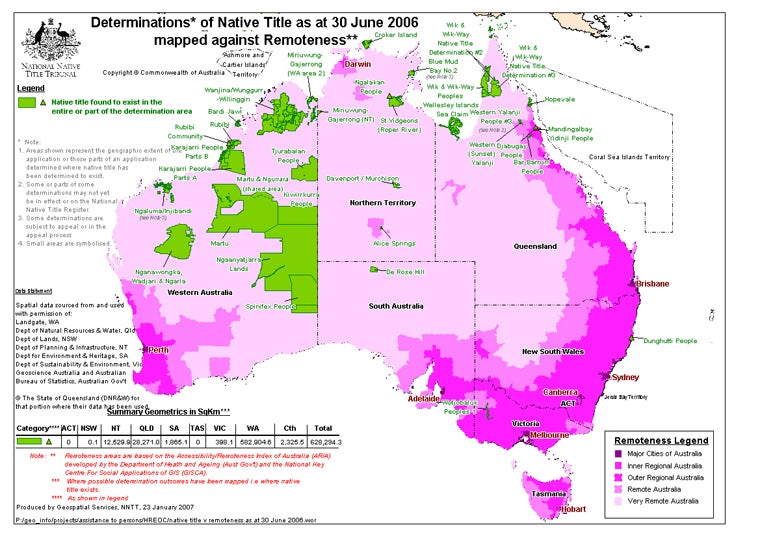

Indigenous traditional owners have varying rights and interests to just over

8.5 percent of the Australian land mass as a consequence of native title

determinations.[9] By June 2006 there

were 60 determinations that native title exists. However, in the majority of

cases the traditional owners do not have exclusive possession of the land.

Traditional owner rights to land are limited to the same customary activities as

those that were practiced centuries ago and recorded by the ‘first

contact’ non-Indigenous colonisers. The claimable land that exists under

the native title regime includes unallocated Crown lands, some reserves and park

lands, and some leases such as non-exclusive pastoral and agricultural leases,

depending on the state or territory legislation under which they were issued.

Across Australia, just over 96 percent of all native title land is classified

as very remote by the Accessibility Remote Index of Australia (ARIA), the

most widely used standard classification and index of

remoteness.[10] In terms of the

size, Western Australia has by far the largest areas of native title land of any

Australian jurisdiction. Ninety two percent of the area of native title

determinations is in Western Australia (WA). A large proportion of native title

land in WA is in the Gibson, Tanami and Great Sandy Desert regions as well as in

the Kimberley. In the other states and territories native title rights and

interests have been recognised over smaller parcels of land. In Queensland land

under native title is in the ‘very remote’ Cape York region and in

the Torres Strait. In South Australia native title interests and rights have

been recognised in the ‘very remote’ north central region of the

state which is partially located within desert regions. In the Northern

Territory native title interests and rights have been recognised over land and

seas in ‘very remote’ regions and in Alice Springs, classified as an

‘outer regional’ by ARIA. In Victoria, native title land is located

‘remote’ and ‘outer regional’ areas and in Tasmania

there are no successful native title claims to date. By June 2006, New South

Wales was the only jurisdiction that successfully achieved a native title

determination in an ‘inner regional’ area. The land parcel is very

small comprising 0.1 square kilometres on the New South Wales Coast.

Overall, the land over which native title interests and rights have been

recognised is some of the most marginal and inhospitable land in Australia.

Chart 12 shows the location of Indigenous land under native title by remoteness.

CHART 12: NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATION AREAS MAPPED AGAINST REMOTENESS -

2006

Source: National Native Title

Tribunal 2006

Indigenous land rights statutes

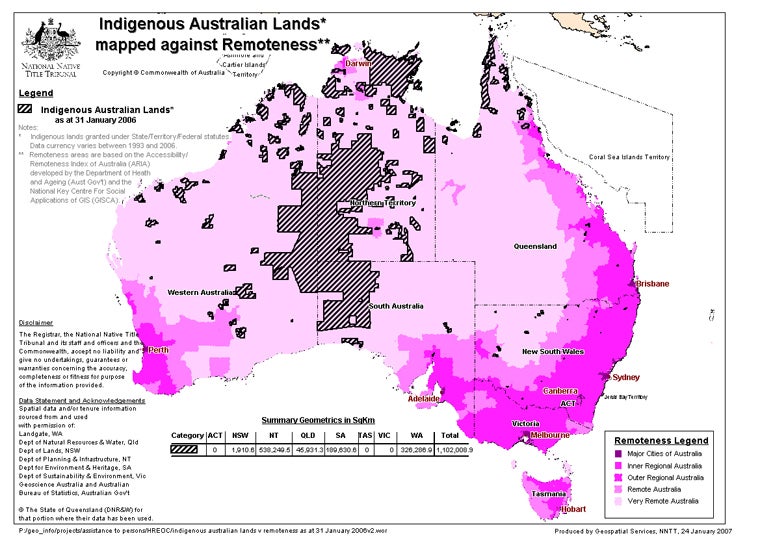

Indigenous lands granted under state, territory and federal statute

constitutes 14.4 percent of the Australian land

mass.[11] Land under statute has

been granted or purchased by governments for Indigenous people since the 1970s.

Like land under native title tenure, while the land area is extensive, the vast

majority of it is marginal, located in desert regions or in remote locations in

the north of Australia.

Chart 13 demonstrates that the land under statutory land rights is

overwhelmingly represented in the central desert regions of Australia. Vast

tracts of Indigenous land traverse Western Australia, the Northern Territory and

South Australia. There are also large tracts of Indigenous land in the remote

north eastern regions of the Northern Territory, in the coastal regions of

Western Australia’s northern belt and the coastal Cape York areas of

Northern Queensland.

The high commercial value of the land in New South Wales (NSW) provides an

exception to the trend for land to be remote and marginal. While the land

granted to land councils in NSW is in many small parcels rather than large areas

of country, some of it is very valuable in terms of its potential for

development, both residential and

commercial.[12]

Chart 13 shows the location of Indigenous land under statutory land rights.

CHART 13: STATUTORY LAND RIGHTS AREAS MAPPED AGAINST REMOTENESS - 2006

Source: National Native Title

Tribunal 2006

Note: This map does not include Indigenous land purchased

by the Indigenous Land Corporation

Other Indigenous communal land tenures

In addition to native title and land rights tenures, Indigenous land has been

purchased on behalf of Indigenous people by the Indigenous Land Corporation

(ILC) since June 1995. Indigenous Australians can apply to the ILC for purchase

of land under the categories of cultural, social, environmental and economic

benefit. Applicants must identify the ways in which the land purchase addresses

dispossession. They must also define a specific purpose for the land under one

of four categories and set achievable milestones and outcomes.

- Applicants are asked to enter into a lease while the ILC owns the land. The

terms of the lease include a staged work plan, including capacity development

activities, and applicants are required to report on and monitor how work is

going.

- Progress towards a land grant depends on successful completion of the work

plan. It is the ILC's opinion that it is usually reasonable to grant land within

three years of buying it. - The ILC's purchase and divestment policy is aimed at ensuring that the land

purchased will remain Indigenous-held and can provide future generations with

cultural, social, environmental or economic benefits.

- The ILC must grant title to land to an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Corporation as defined in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act

2005.[13]

Land purchased by the ILC covers over 5.5 million hectares and cost

almost $170 million by June 2006. Since 1995 the ILC has made a total of 201

land acquisitions, 27 have been acquisitions in urban

locations[14]

The size and location of Indigenous communities

The 2001 census data identifies a total of 458,520 Indigenous people in

Australia. Of these 121,163 were residents in remote and very remote

regions.[15] There are 1,139

discrete communities in remote and very remote regions, of which more than half

(577 in total) have populations of less than 20

people.[16] In most cases, larger

communities represent Indigenous living areas formerly constituted as government

and mission settlements. The smaller populations are outstations or homeland

communities.

[O]utstation communities... had their origins in voluntary and spontaneous

resettlement of Aboriginal country commencing the 1970’s. These

settlements are found predominantly in central Australia, the Kimberly, the top

end of the Northern Territory and the Cape York

Peninsula.[17]

Chart 14 provides information about the number, population size and location

of Indigenous communities.

CHART 14: NUMBER OF DISCRETE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES BY SETTLEMENT SIZE AND

REMOTENESS REGION, 2001

|

Settlement Population Size

|

Major Cities

|

Inner Regional

|

Outer Regional

|

Remote

|

Very Remote

|

Total

|

|

1-19

|

0

|

0

|

6

|

33

|

577

|

616

|

|

20-49

|

0

|

1

|

8

|

36

|

228

|

273

|

|

50-99

|

1

|

7

|

13

|

17

|

64

|

102

|

|

100-199

|

3

|

5

|

12

|

9

|

51

|

80

|

|

200-499

|

1

|

6

|

11

|

11

|

77

|

106

|

|

500-999

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

17

|

18

|

|

1000+

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

2

|

16

|

21

|

|

Total

|

5

|

19

|

53

|

109

|

1,030

|

1,216

|

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics, Housing and Infrastructure in

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities,

2001[18]

Economic development limitations of Indigenous land

The Indigenous land base is not comparable with land in urban environments

and large regional townships. In remote Indigenous communities almost all

services are provided by governments or by church organisations. The land is

inhospitable, and usually cut off from markets and cities by distance and poor

road infrastructure. The tropical north is inaccessible by road during the wet

season which can extend to four months each year. The climate, soil and weather

are not conducive to cultivation, and tourist markets are limited in the

majority of the desert regions. It is therefore difficult to develop and

maintain significant enterprise ventures on Indigenous land.

Experience in remote Australia suggests that a goal of developing

under-developed Indigenous-owned land will not of itself be the driver of

private-sector finance availability. On its own terms, whether this land was

freely alienable or not, much of this land is in the poorest land classes and is

remote from markets.[19]

Economic opportunities are further limited by the fact that land rights

regimes in Australia provide only the most minimal rights to subsurface

minerals. The New South Wales Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW)

provides rights to minerals though significantly excludes rights to gold,

silver, coal and petroleum. In Tasmania under the Aboriginal Lands Act

1995 (Tas), minerals other than oil, atomic substances, geothermal

substances and helium are the property of Indigenous people to a depth of 50

metres. No other land rights regime in Australia provides rights to subsurface

minerals. Indigenous land holders have to apply for licences for mining activity

in the same way as anyone else. While for the most part Indigenous Australians

have no mineral entitlements, the existence of a mining tenement can provide

royalty payments to traditional owners. Information outlining mineral rights

under the land rights legislations of all Australian jurisdictions is provided

at Appendix 1 of this Report.

Although commercial rights are not specifically excluded from the Native

Title Act 1993 (Cth), sections 211(2) and (3) indicate that native title

interests and rights are generally expected to encompass traditional activities.

These include hunting, fishing, gathering, participating in spiritual or

cultural activities and acting for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic,

non-commercial or communal needs.

The case law that has defined and interpreted the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) clarified that subterranean minerals and petroleum are the property of

the states and held this property right is sufficient to extinguish native title

rights. The High Court judgement in Ward[20] determined that

native title entitlements should be characterised as a ‘bundle of

rights’ rather than an ‘underlying title to land.’ The

practical effect of Ward is that the potential economic entitlements of

the claimants are severely restricted. The ‘bundle of rights’

interpretation limits the legal recognition of economic and resource rights.

Only exclusive possession under native title vests land ownership rights in

traditional owners, including the right to exploit mineral resources within the

existing restrictions and caveats of Australian law.

Economic development has never been primary aim of land rights legislations.

If it were, valuable mineral rights would have accompanied the return of the

land as it has in countries with treaties such as Canada, the USA and New

Zealand. In these countries the treaty relationship means that governments have

an obligation to negotiate in good faith and recognise their fiduciary duties to

compensate for dispossession. This has led to large scale financial compensation

settlements that have provided indigenous peoples with a solid foundation for

economic development.

The real value of land returned to Indigenous

ownership under Australian land rights legislation has always been strongly

connected to its potential to compensate for dispossession, restore Indigenous

peoples’ spiritual relationship with the land, and recognise the right to

self-determination. These findings are strongly reinforced by the findings of

HREOC’s survey of traditional owners in Chapter 1 of this Report.

Strategies for economic development on Indigenous land must therefore be made

in full cognisance of the limitations of both the land itself and the land

rights legislative frameworks. The topographic and location limitations of

Indigenous land are integral to any considerations or policy approaches to

improve economic outcomes for Indigenous people. Strategies that work in cities

or on resource rich land are not applicable to the remote, marginal country that

characterises much of the Indigenous ‘estate.’ Governments must look

to approaches that have worked in environments that broadly approximate those

for Indigenous Australians.

99 Year headleases over Indigenous townships

During 2006, the Australian Government began implementing land reforms in the

Northern Territory where the land rights legislation is the jurisdiction of the

Commonwealth. Underpinning the land rights reforms was the 2005 National

Indigenous Council’s (NIC) Land Tenure Principles which were

discussed extensively in last year’s Native Title Report 2005. The

NIC Principles supported the maintenance of inalienable, communal tenure rights

for Indigenous land, but argued to amend land rights legislations ‘in such

a form as to maximize the opportunity for individuals and families to acquire

and exercise a personal interest in those lands, whether for the purposes of

home ownership or business

development.’[21]

In 2006 the Australian Government added a new section 19A to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) to

provide that with ministerial consent a Land Trust may grant a 99 year headlease

over an Aboriginal township to an approved entity of the Commonwealth or the

Northern Territory Government.

The 99 year leasing provision of s 19A of the ALRA has the practical effect

of ‘alienating’ Indigenous communal land. While a lease is not

alienation in fact, it will have the same effect in practice. Ninety nine years

is at least four generations. With potential to create back-to-back leases,

there is a high probability that the leases will continue in perpetuity.

Amendments of the nature of the ALRA are likely to be replicated in other

Australian jurisdictions. During 2006 the Australian Government announced that

it intended to encourage other states and territories to make similar amendments

to their land rights legislations through home ownership funding incentives and

bilateral agreements.

I hope these changes (amendments to ALRA) motivate other state governments to

amend their Indigenous land legislation to facilitate similar opportunities for

Indigenous Australians who reside on community land,’ Mr Brough said.The 2006-07 Budget sees the allocation of $107.5 million towards the

expansion of the Indigenous Home Ownership on Indigenous Land Program.The new tenure arrangements contained in the Bill will enable Aboriginal

people in the Northern Territory to access this new

program.[22]

Obtaining consent for 99 year headleases

The 99 year lease agreements are voluntary. In order to establish a 99 year

headlease, section 19A(2) of the ALRA provides that governments must consult

with the wider Indigenous community of the township, and obtain consent for the

headlease from traditional owners through their representative Land Councils.

The provisions for 99 year headleases are as follows:

A Land Council must not give a direction under subsection (1) for the grant

of a lease unless it is satisfied that:

(a) the traditional Aboriginal owners (if any) of the land understand the

nature and purpose of the proposed lease and, as a group, consent to it; and

(b) any Aboriginal community or group that may be affected by the proposed

lease has been consulted and has had adequate opportunity to express its view to

the Land Council; and

(c) the terms and conditions of the proposed lease (except those relating to

matters covered by this section) are

reasonable.[23]

Section 77A of the ALRA specifies the circumstances under which traditional

owners can give consent as a group.

Where, for the purposes of this Act, the traditional Aboriginal owners of an

area of land are required to have consented, as a group, to a particular act or

thing, the consent shall be taken to have been given if:(a) in a case where there is a particular process of decision making that,

under the Aboriginal tradition of those traditional Aboriginal owners or of the

group to which they belong, must be complied with in relation to decisions of

that kind – the decision was made in accordance with that process; or(b) in a case where there is no such process of decision making – the

decision was made in accordance with a process of decision making agreed to and

adopted by those traditional Aboriginal owners in relation to the decision or in

relation to decisions of that

kind.[24]

Under traditional or agreed decision-making processes, a minority group may

be able to consent to a 99 year headlease on behalf of the majority. Given what

is at stake, it is essential that agreement and consent processes are documented

and authorised by the wider traditional owner group prior to any

negotiations for a headlease. Agreement about what constitutes traditional

decision-making, or agreed decision-making, should be decided in a separate and documented process. Unfortunately the ALRA does not contain a

provision that specifies a discrete process to authorise decision-making.

The step to authorise decision-making is a crucial check and balance. Given that

99 year headleases provide pecuniary benefits to traditional owners, there is

potential for money matters to override traditional considerations. Therefore,

traditional owners must have certainty about who has authority to make

decisions, and how those decisions should occur. This will also ensure

that traditional owners control the pace of decision-making and cannot be rushed

into giving consent by governments who operate on different timetables and

imperatives.

The Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) affords greater

legislative protections to claimants and native title holders in negotiating

consent for land use. The authorisation process for native title Indigenous Land

Use Agreements (hereon referred to as ILUAs) provides a relevant threshold.

Before an ILUA can be registered, the Registrar of the National Native Title

Tribunal must be satisfied that all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure

persons who hold, or may hold, native title in relation to land or waters in the

area have been identified, and that all persons so identified have authorised

the making of the agreement.[25] Authorisation can occur through a traditional decision making process, or

through an agreed process by all persons who hold common or group native title

rights.[26] The National Native

Title Tribunal provided the following explanation of the authorisation process:

- The Native Title Act 1993 requires that one form of Indigenous Land Use

Agreement, the area agreement, be ‘authorised’ by all the persons who hold or may hold native title to the area covered by the

agreement.

- The first step is to make all reasonable efforts to identify all persons who hold, or may hold, native title to the area covered by the

agreement. The second step is to obtain the authority of persons identified in

the first step (the native title group) to make the agreement.

The authorisation of the native title group may be given in one of

two ways:

- In accordance with a traditionally mandated process under the traditional

laws and customs of the native title group to make decision of this kind, for

example if decisions must be made by a council of elders (possibly a few people

who can bind the rest of the group).

- If there are no traditionally mandated decision-making processes, then the

group must agree upon and adopt a decision-making process that will be used to

authorise the decision.

In looking at whether an agreement has been appropriately

authorised the courts have considered:

- Whether there is a body existing under customary law that is recognised by

the members of the group and the nature and extent of that body’s

authority to make decisions binding the members of the group and the fact that

that body actually authorised the relevant action (Moran v Minister for Land

and Water Conservation for

NSW).[27]

- Where the process is one agreed to and involves the holding of meetings, the

purpose of, and agenda for, the meeting where authorisation was apparently

given, and how and to whom notice of the meeting was given, as well as who

attended the meeting and with what authority (Ward v Northern

Territory).[28] [29]

Provisions of this nature should be adopted under the ALRA to

ensure that Indigenous communities and traditional owners are able to give free,

prior and informed consent to 99 year headleases.

The amended ALRA also provides that under section 21C a new Land Council can

be established on a slim 55 percent majority vote of people in a Land Council

region or ‘qualifying

area.’[30] Previous to the

2006 amendments, a substantial majority was required to establish a Land

Council.[31] The 55 percent majority

is of particular concern for traditional owners of large townships. Due to

dispossession, the mission movements, and the centralisation of government

resources in larger communities, many Aboriginal townships are regional hubs

that accommodate large numbers of Indigenous people, many of whom are not the

traditional owners of the town area. Therefore, there are many townships where

traditional owners would not constitute a 55 percent majority.

The following example demonstrates the potential problems of setting 55

percent majority. The Wadeye region is home to over 2,300 people, though

population numbers vary.[32] The

Kardu Diminin people are the traditional owners of the Wadeye township area.

They share their town with members of 19 other clan groups of the broader

Thamarrurr region. Members of regional clans first began to move to the Wadeye

township in the 1930s with the establishment of the mission. This has caused,

and continues to cause, tension in the region. The traditional owners in the

region do not constitute a majority of the people on the township.

Hypothetically, if a vote to establish a new Land Council was to occur in the

Wadeye Thamarrurr region, the traditional owners would not have the numbers to

override a community decision to establish a new Land Council. Should such a

Land Council agree to a headlease and fail to appropriately consult with

traditional owners, under s 19A(3) of the ALRA, this would not nullify the

headlease agreement.

Alternative lease models

The Australian Government will not consider alternative lease models to its

99 year scheme and in 2006 rejected an alternative 40 year lease proposal from

the Wadeye Thamurrur Council. The Wadeye proposal would vest the land title and

governance with the Wadeye Thamurrur Council. The traditional owners argued that

the 40 year model was preferable because it gave them ongoing decision-making

authority over land. According to the CEO of Wadeye's Thamarrurr Council:

The concept of a Town Corporation controlled by the traditional owners, the

Diminin people, is a critical aspect of the lease... The community had a right

to govern itself, and would continue to oppose federal government

plans.[33]

The Wadeye proposal was prepared with expert legal advice, though the

Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs rejected it on

the grounds that banks would not provide finance for mortgages and business

proposals on 40 year lease

tenures.[34]

It's been rejected on economic grounds, it's simply unsustainable...You don't

get, and will not get, banks to back the sort of financial investments that they

may be asked to make in regards to substantial

businesses.[35]

Despite differing views on the views on the financial viability of lease

terms, the Minister will have the last word on this matter as $9.5 million in

housing funding for Wadeye is contingent on the Thamurrur Council agreeing to a

99 year headlease.

[T]he Minister is using as a bargaining chip, money that has already been

allocated to Wadeye. He's held up $9.5 million in housing funding,... Initially

he said he was holding it up until our people stop fighting and we're told the

day before yesterday that the $9.5 million that's been frozen in a trust account

in Darwin won't be freed up until this lease is

signed.[36]

The Australian Government’s intransigence over the Wadeye proposal is

evidence that it will not take a research-based approach to land reform by

trialling different land tenure schemes such as the one proposed at Wadeye.

In fact, there are many alternative options to 99 year leases. In my Native Title Report 2005 I provided evidence that it is currently

possible to set up leases under every piece of land rights legislation in

Australia except one (the Victorian Aboriginal Lands Act 1991). Leases

can be for both residential and commercial purposes. Under land rights statute,

leases require traditional owner consent, and depending on the length of the

lease, Ministerial consent may also be required. Under the native title regime,

leases may be issued by governments if the native title representative body

agrees through an Indigenous Land Use

Agreement.[37] In many Indigenous

townships these leases are currently operating on communal lands. The benefits

of these leases are that traditional owners retain decision-making control over

the land. Under the Government’s 99 year headlease plan, the

‘established entity’ will make the decisions affecting all future

development on Indigenous land.

International Experience

Perhaps one of the most compelling arguments against the Australian

Government’s individualised land lease scheme is that it is not based on

successfully evaluated models elsewhere in the world. In fact, international

evidence demonstrates poor outcomes for Indigenous people when communal tenures

are individualised. While individual title may provide appropriate structures

for asset management and accumulation in Western urbanised economies, it is not

a model that is readily transferred to economies based on communal rights. There

is ample evidence from New Zealand, the United States and the World Bank

confirming these shortcomings.[38]

I covered this issue extensively in last year’s Native Title Report

2005 providing detailed examples of the problems associated with this

approach. It is difficult to comprehend the Australian Government’s

determination to implement a strategy that has been trialled, tested and shown

to be flawed in other OECD countries. In fact, due adverse outcomes, the United

States, New Zealand and World Bank are reversing past policies that facilitated

individual titling. During the 1970s, the World Bank evaluated individual tenure

reforms and found that they led to:

- significant loss of land by indigenous peoples;

- complex succession problems – that is, who inherits freehold or

leasehold land titles upon the death of the owner; - the creation of smaller and smaller blocks (partitioning) as the land is

divided amongst each successive generation; and - the constant tension between communal cultural values with the rights

granted under individual

titles.[39]

Recent research about similar reforms in Kenya in the 1950s

corroborates the findings from New Zealand, the United States and the World

Bank.[40] The findings from 40 years

of individual titling in Kenya demonstrate no real economic benefit and limited

economic leverage opportunity. In fact, formal, individual title made the land

more vulnerable to bank foreclosure to recover debt. Some of the recorded

disadvantages include:

- there was no evidence supporting a link between formal title and access to

credit; - that only a very small minority of Kenyans had used title to secure loans

and they were generally the richer and more productive farmers; - there had been some loan defaults leading to foreclosure and loss of the

asset; - families were hesitant in using the asset as collateral for enterprise

development for fear of losing the family land; - in passing the asset on to family members there were negative distributional

consequences, including the sale of the asset; - that the sale of the asset occurred in emergencies such as a need to pay

medical expenses; and - that women were significant losers when titles were formalised due to

customary practices that ensured absolute legal ownership with the male head of

the family.[41]

The idea of utilising the ‘dead capital’ of communal

land is an argument put by many modern nations struggling to economically engage

indigenous populations. Some of the arguments that promote individual title come

from the difficulties encountered by Maori and Australian Indigenous

corporations in attempting to use communal land as security for business

development.[42] Hernando de

Soto’s documented research into the formalising land title in Peru is

perhaps at the forefront of arguments advocating individual land title.

[B]ecause the rights to these possessions are not adequately documented,

these assets cannot readily be turned into capital, cannot be traded outside of

narrow circles where people know and trust each other [and] cannot be used as

collateral for a loan.[43]

At a Land and Development Symposium in August 2005, these theories for the

use and registration of customary land were discussed in relation to the Asia

Pacific. Academic representatives from the Asia Pacific School of Economics and

Government, the University of the South Pacific and the Australian National

University promoted the formalisation of customary title, arguing for secure

individual title.[44]

[C]ustomary land is dead capital, the declining productivity of land would

cause higher poverty and insecure access to land had dissuaded long-term

investment into fixed

infrastructure.[45]

Arguing against this position was the Papua New Guinean Land Titles

Commissioner, Josepha Kanawi, who put forward an argument for the registration

of land to protect customary title. Along with other PNG representatives, he

argued that customary title provides security, that the registration of

customary land should be voluntary, and that customary titles should be able to

be used as security for bank

loans.[46]

Customary land ownership...[provides]...security for the people, but ... it

is under pressure from social and economic change, and therefore must be

protected by registration.[47]

Banks in Papua New Guinea and Kenya have rejected the use of customary lands

as security for loans. PNG banks ‘made it clear that they would not accept

customary land as security for loans until it was converted to either freehold

or state land.’[48] In New

Zealand banks indicated that ‘business proposals involving Maori land

might be of lower priority for institutions able to obtain easier business

elsewhere.’[49] However, while

communal title has been rejected by banks to leverage loans, formal title on

small land holdings has not necessarily convinced banks of sufficient loan

security. For example in Kenya, ‘banks tend to shun small scale

(particularly rural or agriculture-dependent) land holders [and land title] does

little to change these

biases.’[50] The associated

potential for loss of the land asset through loan default is further

disincentive to using land title for collateral.

It is essential that governments ensure that all stakeholders in lease

negotiations are well informed of potential pitfalls as well as benefits and

opportunities. Ultimately traditional land owners should be well armed with

information and able to give informed consent to whichever economic model suits

their purposes. There may be groups of traditional owners who decide to give

consent to 99 year leases once they have considered all available evidence about

its likely impacts. The concern under the current ALRA provisions is that the

consent threshold is too low and it lacks the necessary checks and balances. In a non-Indigenous context, such standards for negotiation and consent

over land title would never be tolerated. It is essential that

the Australian Government provide the highest level of protections for

traditional land owners.

Use of the Aboriginal Benefits Account to pay for

Government 99 year headleases

A further concern about the administration of 99 year headleases is that they

are to be funded, at least initially, from the Aboriginal Benefits Account

(ABA). The ABA is an account that contains Aboriginal mining royalty monies. The

only express direction on the use of ABA is that it is to be used ‘to or

for the benefit of Aboriginals living in the Northern

Territory.’[51] Under the

amendments to ALRA, a new s 64(4A) states that payments must be debited from the

ABA to be used for acquiring, administering and paying rents on 99 year

leases.[52] To quote Minister

Vanstone:

The scheme is designed to be self financing in the longer term with sub-lease

rental payments covering the costs. Until then all reasonable costs will be met

from the NT Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA), subject to consultation with the

ABA Advisory Committee.[53]

Northern Territory Land Council estimates expect head leasing to costs up to

$15 million over 5 years. Other commentators suggest that this is a conservative

estimate.[54] This is a significant

portion of the ABA which provides approximately $30 million in royalties per

year. Spending ABA money to pay for headlease rental will significantly reduce

the overall amount available for Land Councils and the range of land management

and other programs that are funded through ABA. Minister Brough’s Second

Reading Speech for the ARLA Amendments Bill ominously observed that ‘in

future, Land Councils will be funded on workloads and

results.’[55]

The use of

ABA funds to pay for headleases is contrary to its purpose. The purpose of the

ABA is to provide benefit to Indigenous people above and beyond basic

government services. The administrative costs of land leasing are basic

government services. Furthermore, the use of the ABA for headleases is targeted

distribution of funds to communities that sign to the leases, while others will

not benefit at all.

By taking control of Indigenous land and the ABA funds, the Australian

Government is limiting the capacity for Indigenous Australians to be self

determining and self managing. On the one hand the Government has argued that it

is promoting a culture of Indigenous economic independence through amending

ALRA, and on the other it takes away the discretionary funds and control of land

that provide the capacity to do so. In 1999, the House of Representatives

Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs report Unlocking the Future recommended:

As a reflection of its core principles, the Committee agrees that Aboriginal

people should take as much responsibility as possible for controlling their own

affairs. This applies too, for the administration of the...

(ABA).[56]

Modifications to the permit system

Under the current permit system in the Northern Territory, traditional owners

can regulate and restrict access to people entering Indigenous land. Visitors

require a permit in writing from the relevant Land Council or traditional

owners.[57] However, in 2006, the

Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs responded to a

question in Parliament by announcing that it was time to remove the permit

system.[5] Within a month the

Minister issued a media release calling for written submissions in response to

an Australian Government discussion paper on the permit system in the Northern

Territory.

...the permit system has created closed communities which are restricting the

ability of individuals to interact with the wider community and furthermore to

participate in the real economy.The permit system has not acted to protect vulnerable citizens, including

women and children, and in fact makes scrutiny over dysfunctional communities

more difficult.[58]

The Governments Permit Discussion

Paper[59] contains five options

for action. In summary they are:

- authorise access for people with estates or interests granted under section

19 of the ALRA ; - provide open access to communal or public space and maintain the current

permit-based system of restricted access to non-public spaces; - widen the current permit-based system by expanding the categories of people

eligible to enter Aboriginal land without being subject to permission. - reverse the current restrictive permission-based access system to a liberal

system with specific area exclusions. Access to Aboriginal Land would not

require a permit unless a particular area was designated as restricted; and - remove the permit system altogether and replace with the laws of trespass,

with any necessary modification for Aboriginal land.

Amendments to the permit system are part of the Government’s

‘normalisation’ of Indigenous townships. The Government intends to

open up Indigenous land to people who are neither traditional owners nor current

residents and thereby increase interaction between remote Indigenous people and

with the wider Australian economy.

At the heart of debate about the permit system is the right of traditional

owners, through their representatives, to decide who to include or exclude from

entry onto Indigenous land. Along with this is the right to information about

who is entering or exiting Aboriginal land. As the Minister for Families,

Community Services and Indigenous Affairs correctly observes that:

given the vastness of the Aboriginal land estate and the consequent

difficulties in applying normal laws of trespass, the permit system has operated

to respect the privacy and culture of Aboriginal

people.[60]

The permit system operates as a kind of passport system allowing Aboriginal

people to exercise property rights on an equal footing with other Australians.

The Northern Land Council made this point in its submission to the Reeves

inquiry:

Traditional Aboriginal owners of Aboriginal land, like any other landowners,

have as part of their title to the land the right to admit and exclude persons

from their land. This is a fundamental aspect of land ownership under the

general law and is also fundamental to the achievement of the aims of the Land

Rights Act.[61]

The question of

whether a permit system is discriminatory was examined in the High Court case of Gerhardy v Brown.[62] While

the High Court found that the permit system established by s19 of the Pitjanjatjara Land Rights Act was a racially discriminatory measure,

contrary to s10 of the Racial Discrimination Act, it also found that s19

was a ‘special measure’ pursuant to s8 of that Act and was therefore

valid. Consequently, the permit system provides equality before the law and is a

special measure to ensure non-discrimination.

Section 8 of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) is modelled on

Article 2(2) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) [63] which obliges parties to the

Convention to undertake, when warranted, special measures to ensure the adequate

development and protection of certain racial groups or individuals belonging to

them, for the purpose of guaranteeing them the full and equal enjoyment of

rights and fundamental freedoms. Special measures should not bring about the

maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups after the objectives

of the measures have been achieved.

The Minister’s argument that the permit system has prevented economic

development, and that its abolition will provide economic benefits requires

close scrutiny. The FaCSIA Discussion paper, Access to Aboriginal Land under

the Northern Territory Aboriginal Land Rights Act – Time for a change? Observes that,

[m]any Aboriginal communities on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory

are already remote geographically. The permit system has operated to maintain or

even increase that remoteness – both economically and socially. It has

hindered effective engagement between Aboriginal people and the Australian

economy.[64]Liberalisation would also bring economic benefits that would help to promote

the self reliance and prosperity or Aboriginal people in remote

communities.[65]

The Minister argues that if Indigenous lands are opened to non-Indigenous

interests, there is a high probability that outside operators will take the

opportunity to develop businesses, especially because the commercial competition

in these communities is very limited. However, I believe the economic benefits

to the Indigenous community are likely to be minimal. They may include greater

choice as consumers and, at most, the ability to secure waged employment with a

business operator. Nevertheless, ABS data demonstrates that the private sector

is not a good employer of Indigenous

people.[66] There is therefore some

risk and great cost in giving private operators free reign on communal lands and

assuming that they will assist in improving employment outcomes for Indigenous

people. By giving private operators access to Indigenous lands, an opportunity

is lost for the Indigenous residents. In the case of enterprises involving

tourism for example, rather than owning the business, Indigenous land owners

become the employees of companies who in turn capitalise on Indigenous land and

culture. The most likely consequence of the Government reforms will be the

profit of non-Indigenous operators from undeveloped markets.

To continue the tourism example, an alternative arrangement would be for

governments to support the maintenance of the permit system while providing

opportunity for Indigenous people to develop or become partners in joint venture

tourism enterprises. Maintaining restricted access to the land adds rather than detracts from the unique nature of the tourism experience and

ensures that Indigenous Australians don’t have to compete in an open

market with highly resourced operators. A strategy such as this one actually

achieves the Government’s objective of improving economic outcomes for

Indigenous Australians.

There are also environmental impacts to be considered. The land degradation

caused by unchecked tourism and four wheel drive activity would be impossible to

monitor in national parks and on Aboriginal lands without a permit system. Open

access would require greater vigilance in protecting cultural heritage, sites of

significance, and sacred sites. This too is a resource issue and one that is not

addressed in the Australian Government’s Discussion Paper. Ultimately, the

degradation of the land is the degradation of the most precious asset of

Indigenous Australians, both in economic and cultural terms.

As it stands, the Discussion Paper does not canvass enough options for

economic development. It does not consider for example, charging fees for the

issue of permits. Currently there are some instances where permit fees are

charged to visit areas such fishing spots, (on a per car basis), and art

centres.[67] If the Government is

concerned about increasing economic opportunity for Aboriginal people, one

option under the permit system could be to charge entry to popular sites.

Ultimately the Government has responsibility to canvass the widest range of

options and to engage Indigenous Northern Territorians in the development of an

economic development plan.

Discontinuation of funding and services to

homelands

As a consequence of the Homeland Movement of the 1970s, thousands of

Indigenous Australians moved out of missions and settlements and back onto

traditional lands. The decision to return to country was primarily to resume

cultural, spiritual and ceremonial connections and responsibilities to land.

It is estimated that approximately 20, 000 Indigenous Australians live in

communities of less then 100 people. The size of homeland communities varies,

some with less than 50 people, and others with 100 and

more.[68] According to the ABS, 70

percent of Indigenous Australians over 15 years of age recognise homelands or

traditional country. Affiliation with traditional country increases with

remoteness; 86 percent of people living in remote areas claim affiliation

compared with 63 percent in non-remote

areas.[69]

In 2005 and 2006 the Australian Government signalled an intention to reduce

or withhold services to homeland communities. The Minister for Families,

Community Services and Indigenous Affairs asserted:

The investment and effort will focus on remote Aboriginal communities or

towns that have access to education and health services. This will include many

small settlements. However, if people choose to move beyond the reach of

education and health services noting that they are free to do so, the

government’s investment package will not follow them. Let me be specific

– if a person wants to move to a homeland that precludes regular school

attendance, for example, I wouldn’t support it. If a person wants to move

away from health services, so be it – but don’t ask the taxpayer to

pay for a house to facilitate that

choice.[70]

National policy does not determine formulae for health and education service

provision. These are determined by the states and territories. For example,

education provision in the Northern Territory is based on a student to teacher

ratio. A fully qualified teacher is provided when there are 22 attending

students aged between six to twelve years of age. Homeland communities are

usually serviced by larger ‘hub’ communities. The school at

Maningrida in the Northern Territory provides services to 12

‘satellite’ homeland communities and attracts a teacher formula

based on the total number of students attending in region. Teachers visit

homelands for varying numbers of days per week depending on the teacher

allocation that the homeland attracts under the formula.

At this stage there is insufficient detail to assess whether homelands and

other small communities will be disadvantaged as a result of the Australian

Government’s funding agreements. It will be through bilateral agreements

that the Australian Government will be able to link funds to preconditions as it

is doing with housing.

Shire councils to replace Indigenous community

councils

Alongside the land tenure reforms is the Australian Government’s plan

to reform the Indigenous local government system by rationalising the large

number of small local community councils and replacing them with larger regional

shire councils. The Australian Government has supported the Northern Territory

Government’s plan to reform its community councils and the Queensland

Government is finalising the transition to shire council arrangements.

Currently, across Australia remote communities are governed by local

governments or community councils that are based within each community. In the

Northern Territory for example, the Government developed a plan to replace its

56 remote Indigenous councils with nine shire councils. The four municipal

councils in Darwin, Palmerston, Alice Springs and Katherine will remain

unchanged. The Northern Territory Minister for Local Government argued that the

shire council model is designed to improve governance and service delivery to

remote communities.

Change will ensure people in the regions have access to the services and

experts many of us take for granted in the urban centres...The new local

government will create a framework of certainty and better and more reliable

services.[71]

Queensland has commenced a four year transition process to transform

Aboriginal Councils into full Shire Councils. The stated intention of the

transition is to improve governance. The Shire and Island Councils will be

responsible to build, operate and maintain a range of infrastructure and to

assist in the delivery of

services.[72]

The transition to shire councils is an effort to rationalise resources and

concentrate high level administrative expertise at the regional level. While

this may achieve efficiencies in terms of the cost of local government

administration it will also impact on Indigenous employment options in remote

communities. The removal of community councils, including community housing

associations will remove one of the few sources of remote employment.

As the lack of employment opportunity in remote communities is one of the

main impediments to economic development, governments must take care to balance

policy approaches. If rationalising housing services reduces employment, then

one saving will mean another cost. In order to benefit from any home ownership

incentives or policies, Indigenous Australians require employment.

Housing and home ownership

During 2005 and 2006 the Australian Government announced a number of

incentives to increase the rates of Indigenous home ownership and reduce

Indigenous dependence on subsidised housing in remote communities. During the

publicity that surrounded the initiatives, private home ownership was described

as a right for all Australians who can afford this goal. In 2005 the Prime

Minister had the following to say:

I’m a supporter of home ownership for everybody who can afford it, I

really am. And I don’t think there should be any distinction between

Indigenous people and the rest of the community. I think it’s patronising.

I think it’s discriminatory to take the view that somehow or other home

ownership is something for the white community but not for the Aboriginal

community...Now I’m not trying to undermine the Native Title Act but what

I’m saying is that where we can develop methods of private home ownership

within Indigenous communities, we should do

so.[73]

Just over 7 percent of remote Indigenous Australians own, or have a mortgage

over a home. Australia-wide the rates of Indigenous home ownership are higher at

27 percent.[74] Nevertheless,

Indigenous Australians fall well behind the 74 percent of non-Indigenous

Australians who are either buying or own their home outright.

The Australian Government’s remote housing strategy is part of a reform

package to encourage Indigenous Australians to embrace a culture of asset

accumulation and management with paid employment as its foundation. According to

the Government, land tenure reforms on communally owned land have been required

in order to make home ownership possible. The Attorney General's Department

along with the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

(FaCSIA) and Indigenous Business Australia have collaborated in the home

ownership strategy. In fact initiatives for home ownership were released almost

simultaneously with the announcement of the proposed amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) in 2005. The

home ownership initiatives included:

- funding for Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) for the Community

Homes program which will provide low cost houses for purchase at reduced

interest rates in remote communities; - an initial allocation from the Community Housing and Infrastructure

Program to reward good renters with the opportunity to buy the community

house they have been living in at a reduced price; - using the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) program to

start building houses, support home maintenance, and to maximise employment and

training opportunities.[75]

While the initiatives are described as ‘Australia-wide

measures’ they are exclusively available to states and territories if, or

when, they amend their land rights legislations to allow for 99 year leases. To

quote the Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs:

These programs will be available to all States that follow the Australian and

Northern Territory government’s lead to enable long term individual leases

on Aboriginal land... The Australian Government will consult with the States to

promote any necessary amendment of State Indigenous land rights regimes to

ensure access to the new

programs.[76]

The Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs has

committed over $100 million to increase remote home ownership from 2006 to 2010.

However the Northern Territory is the only jurisdiction in a position to access

this funding to date. Other states are beginning the process of reviewing their

land rights legislations and it is not certain whether they will include

provision for 99 year leases.

From 1 July 2006, the Australian Government is providing $52.9 million plus

capital of $54.6 million over four years for initiatives to promote Indigenous

home ownership on community title land.The measure will assist Indigenous families living in communities on

Indigenous land to access affordable home loan finance, discounts on purchase

prices of houses, and money management training and

support.[77]

The Australian Government has targeted its programs and incentives to a

select group of communities in the Northern Territory; Galiwinku, Tennant Creek,

Katherine and Nguiu.[78] Forty five

new houses will be constructed for private purchase across Galiwinku and Nguiu.

Discounts of up to 20 percent on house purchase prices will be available in

other communities.[79] The discounts

will be available to good renters and there is sufficient funding for up to 160

low interest home loans specifically targeted to

remote.[80]

FaCSIA will also provide money management training and support to the four

Northern Territory communities and two Western Australian communities through a MoneyBusiness program. This program is a partnership with the ANZ Bank

and is designed ‘to develop skills in budgeting, bill paying and

saving.’[81]

The incentives and announcements of 2005 and 2006 are likely to be a

precursor to broader reforms in Indigenous housing. In June 2006 the Minister

for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs announced a

comprehensive audit of Australian Government and State and Territory Government

funding on public housing.[82] Accompanying the announcement were numerous statements about the cost of

Indigenous housing and concerns about whether the states and territories were

adequately managing and contributing these programs. In 2006 the Government

released a discussion paper to raise potential directions for Indigenous

housing: Community Housing and Infrastructure Program (CHIP) Review Issues

Paper. The Best Way Forward: Delivering housing and Infrastructure to Indigenous

Australians (Hereon referred to as the Issues

Paper).[83]

While the Review has not been released, the topics canvassed in the Issues

Paper foreshadow the areas of reform. They include the rights and

responsibilities of tenants, rent payments and collection, measures to increase

home ownership, improved access to mainstream public housing, and strategies to

avoid duplication of municipal services and

infrastructure.[84]

The remote Indigenous housing profile

The dominant housing tenure for Indigenous people in very remote communities

is community rental housing. In 2001, 84 percent of all remote Indigenous

households were renters. Approximately seven percent of remote Indigenous

householders are home owners.[85]

Community rental housing is built and maintained by governments. Over the

past 30 years, somewhere between 500 and 1,000 community rental houses have been

built each year in Indigenous communities across Australia. Once built, the

houses are vested in Indigenous community organisations for ongoing management

and the collection of rental payments. The medium weekly rental payment in very

remote regions is $42 per

household.[86] Rents are either set

at per person or per household rate and are generally lower than rents in larger

townships and cities. Rental payments for community housing covers some of the

asset maintenance and other recurrent costs.

The provision of housing in remote communities is failing to meet the demands

of the growing Indigenous population. The problems are both with the number and

size of houses and the quality of the housing stock. In 2001, 41 percent of

remote Indigenous households reported problems with overcrowding. Fifty two

percent of the Indigenous remote population reported living in dwellings

requiring at least one extra bedroom, compared to 16 percent in non-remote

areas.[87] Just over 58 percent of

remote Indigenous Australians reported major structural problems of their

dwellings at almost double the incidence of non-remote at 32.5 percent. The

Australian Bureau of Statistics summarised the problems in remote communities in

the following terms: ‘overcrowding and lack of adequate facilities such as

a clean water supply and sewerage disposal are particularly problematic in

remote areas.’[88]

Indigenous housing programs and funding

The responsibility for Indigenous public and community housing is shared

between the Commonwealth and the states and territories. However, the Australian

Government is the main contributor of funding, providing 73 percent of total

funds, while states and territories contribute the remaining 27

percent.[89] The annual contribution

of the Australian Government to Indigenous housing is more than $375 million. It

is clearly a large commitment and one which accounts for 30 percent of all

Australian Government spending on public and community

housing.[90] The program through

which the funding in administered is the Community Housing and Infrastructure

Program (CHIP). In remote regions CHIP provides housing infrastructure and

funding to maintain essential municipal infrastructure and sanitation

infrastructure.[91] Six hundred and

sixty Indigenous community-controlled housing organisations throughout Australia

manage funding for local infrastructure and maintenance as well as collecting

rental on Indigenous community houses. These entities provide employment for

Indigenous people in remote and regional communities, though it is likely that

these organisations will be rationalised into regional entities in the near

future.

The Indigenous Business Australia home loans program

In the 2006-07 Budget the Australian Government announced a $107.4 million

package over four years to develop home ownership opportunities on Indigenous

land. This funding will be used to build houses and to provide loans to

Indigenous people on communal lands where individual leases are possible. The

Australian Government’s remote home ownership program is managed through

Indigenous Business Australia’s (IBA) Community Homes program.

IBA will expand its home lending program, Community Homes... and will

manage and deliver incentives to assist in overcoming the barriers of the high

cost of housing, low employment and income levels in remote

areas.[92]

According to Indigenous Business Australia the additional funds will expand

its home lending program, by supporting 460 families or individuals to purchase

their own home.[93] Community

Homes will provide access to home loan finance in all states and territories

where land title enables an individual long term interest on a block of land.

IBA will work with the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous

Affairs (FaCSIA) to provide discounts on the purchase price of houses and

financial literacy training for eligible

participants.[94] Incentives also

include purchase price discounts on existing community rental homes of up to 20

percent for Indigenous families with a good rental record. These incentives are

part of the Good Renter Scheme initiative.

The Community Homes scheme will offer loans to low income earners with

incomes starting from $15,000. Maximum repayments will vary according to income

level, starting at 15 percent of gross income for those on the minimum income

level and up to 30 percent of gross income for those on higher incomes. For

those on lower incomes, commencing interest rates on loans will start from zero

percent per annum incrementing by 0.2 percent each year up to the maximum rate

of 6 percent per annum. Grants for co-payments of up to $2,590 each year for the

first ten years will assist eligible low income borrowers to repay the loan

within a loan term of 30 years. IBA will pay up to $13,000 for loan

establishment costs including legal costs, surveys, property valuations,

independent legal and financial

advice.[95]

Home buyers in Australia

Housing affordability is determined by many factors. In attempting to

determine whether remote Indigenous Australian will be able to benefit from the Community Homes scheme, it is necessary to consider employment

opportunities and earning capacity. A typical Australian home buyer for example,

is one who lives in a city and depends on an urban economy to generate work

opportunities and an income that will sustain a mortgage over a 30 year period.

First home buyers are typically couples aged approximately 35 years. They have a

life expectancy up to 78 years for males and 83 years for

females.[96] They have above average

incomes and in Australia, a growing proportion of first home buyers have two

incomes. The majority of owner-occupier households reported gross weekly incomes

in the top two income brackets.[97] This is an average weekly income of $612 to $869 or at the highest bracket $870

or more. The first home buyer relies heavily on debt finance and during 2004 and

2005 the average loan for first home buyers was $210,000. The average weekly

housing costs for first home buyers were

$330.[98]

A domestic unit with an income of say $60,000 per annum may buy a dwelling

and land package for $240,000, and spend $15,000 per annum over anywhere between

the next 20 and 30 years in paying off this capital. In addition, such domestic

units undertake to meet the recurrent costs of housing maintenance, so that

their asset does not depreciate, as well as paying recurrent government taxes