Native Title Report 2008 - Case Study 1

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Native Title Report 2008

Case study 1

Climate change and the human rights of Torres Strait Islanders

![]() Download in PDF

Download in PDF

![]() Download in Word

Download in Word

- 1 Potential effects of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands

- 2 Climate change and the human rights of Torres Strait Islanders

- 3 What is already being done?

- 4 What next?

- 5 If things continue as they are? Torres Strait Islanders rights of action

- 6 Conclusion

Imagine the sea rising around you as your country literally disappears

beneath your feet, where the food you grow and the water you drink is being

destroyed by salt, and your last chance is to seek refuge in other

lands...[1]

This is a reality that a group of Indigenous Australians – the Torres

Strait Islanders – are facing. If urgent action is not taken, the region

and its Indigenous peoples face an uncertain future, and possibly a human rights

crisis.

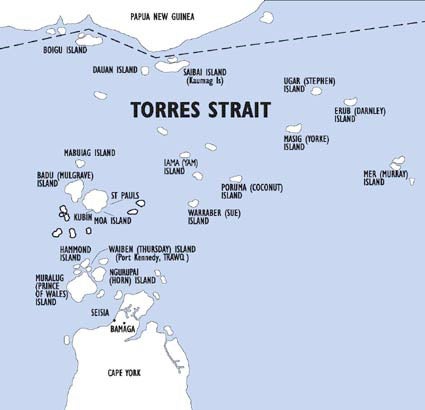

The Torres Strait Islands are a group of over 100 islands spread over

48,000km2, between the Cape York Peninsula at the tip of Queensland,

and the coast of Papua New Guinea.

It is a unique region, geographically and physically, and it is home to a

strong, diverse Indigenous population. Approximately 7,105 Torres Strait

Islanders live in the Torres Strait region, in 19 communities across 16 of the

islands.[2] Each community is a

distinct peoples – with unique histories, traditions, laws and customs.

Although the communities are diverse, the islands are often grouped by

location[3], and together they form a

strong region whose considerable influence is evidenced by the very existence of

native title law today.

The Torres Strait is home to the group of Islanders from Mer who first won

recognition of native title, with Eddie (Koiki) Mabo triggering the land rights

case which recognised Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders’

native title to the land and affirmed that Australia was not terra nullius (belonging to no one) when the British arrived. It is also home to a group

of Aboriginal people, known as the Kaurareg of the Kaiwalagal (inner) group of

islands.

The Islanders were also successful in forming their own governance

structure:

In 1994, in response to local demands for greater autonomy, the Torres Strait

Regional Authority (TSRA) was established to allow Torres Strait [I]slanders to

manage their own affairs according to their own ailan kastom (island

custom) and to develop a stronger economic base for the

region.[4]

Additionally, the region has its own flag symbolising the unity and identity

of all Torres Strait Islanders[5], and

the area is subject to a bilateral treaty with Papua New Guinea which recognises

and guarantees their traditional fishing rights and traditional customary

rights.[6]

Map 1: The Torres Strait region

Despite these strengths, many Australians would be hard pushed to locate the

region on a map, and the Torres Strait Islands and its Indigenous peoples are

often overlooked in policy, research and Indigenous’ affairs discourse in

Australia. This is also true for many issues on the islands related to the

environment. As one researcher has put it, the Torres Strait Islands have

effectively been ‘left off the map in research on biophysical change in

Australia’.[8]

Yet the Islanders’ cultures, societies and economies rely heavily on

the ecosystem and significant changes to the region’s environment are

already occurring. For example, in mid 2005 and in early

2006[9], a number of the islands were

subject to king tides which were so high that the life of one young girl was

threatened, and significant damage was

caused.[10] Although there is no

proof that these were attributable to climate change, Islanders believe that it

is climate change that is threatening their existence.

Anecdotally, Islanders have voiced their concerns to me about the impact of

climate change and the visible changes that are already occurring, such as

increased erosion, strong winds, land accretion, increasing storm frequency and

rougher seas of a sort that elders have never seen or heard of before. They have

seen the impact these events have had on the number of turtles nesting, their

bird life and sea grass. They feel that their lives are threatened both

physically and culturally.[11]

The potential impacts of climate change are severe. Ultimately, if

predictions of climate change impacts occur, it poses such great threats to the

very existence of the Islands that the government must seriously consider what

the impact will be on the Islanders’ lives, and provide leadership so that

cultural destruction is avoided. As the United Nations Permanent Forum on

Indigenous Issues recognised ‘Indigenous peoples, who have the smallest

ecological footprints, should not be asked to carry the heavier burden of

adjusting to climate

change:’[13]

It is ironic that Torres Strait Islanders have been able to weather 400 years

of European colonisation as a distinct Indigenous entity, only to have to face

the problem of cultural annihilation as a result of rising sea level due to the

greenhouse effect.[14]

Because of its geography, with many of the Islands being low-lying coral cays

with little elevation, the Torres Strait Islands will be the inadvertent litmus

test for how the Australian and Queensland governments distribute the costs and

burden of climate change:

Socially, climate change raises profound questions of justice and equity:

between generations, between the developing and developed worlds; between rich

and poor within each country. The challenge is to find an equitable distribution

of responsibilities and

rights.[15]

The lessons learned will have wide application. FaHCSIA states that there are

‘329 discrete Indigenous communities across Australia located within 10

kilometres of the coast. The majority of these communities are located in remote

locations.’[16]

1 Potential effects of climate change on the Torres

Strait Islands

Both domestic and international research on climate change impacts identify

the difficult situation that the Torres Strait Islanders face in order to

survive:

Torres Strait [I]slanders and remote [I]ndigenous communities have the

highest risks and the lowest adaptive capacity of any in our community because

of their relative isolation and limited access to support facilities. In some

cases the Torres Strait islands are already at risk from

inundation.[17]

Primarily there will be three major impacts with considerable flow on effects

which overlap and form a cycle of destruction:

- A temperature rise is predicted. ‘By 2070, average temperatures are

projected to increase by up to

6◦C.’[18] - A rise in sea level is predicted. ‘While global average sea level rise

is projected between 9 and 88cm by 2100, sea level rise around some areas of the

Australian coast and the Pacific region has recently shown short term

larger-than-average

variation.’[19] Some of the

Islands in the Torres Strait are barely a metre above sea level. However, the

impact that sea level rise will have on the Islands could vary. It could include

loss of land, sediment supply and possibly island growth, or increased

inundation events. - An increase in severe weather events is predicted. ‘Rainfall patterns

are also likely to become more extreme, with projected changes of between +17 to

-35 per cent (in the wet and dry seasons respectively compared to 1990 levels)

in the region. This suggests the potential for heavier downpours during the

monsoon as well as more extended dry

spells.’[20]

These three primary impacts will flow on to potentially effect every aspect

of society, including:[22]

- reduced freshwater availability

- greater risk of disease from flooded rubbish tips and changing mosquito

habitats - erosion and inundation of roads, airstrips and buildings near the shoreline

- degradation of significant cultural sites, such as graveyards near the

shoreline - change in the location or abundance of plants and animals (and their

habitat), such as turtles, dugongs and mangroves. This could extend to a

complete loss of some plants and animals - change in coral growth or coral bleaching

- inundation or destruction of essential infrastructure such as housing,

sewerage, water supply, power - inability to travel between islands

- movement of disease borne/ pest insects from the tropical north

- loss of land, accretion or creation of

land.

Text Box 1: Impacts of climate change on small islands

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change summarises the impacts of

climate change on small islands

as:[23]

Small islands, whether located in the tropics or higher latitudes, have

characteristics which make them especially vulnerable to the effects of climate

change, sea-level rise and extreme events.

Deterioration in coastal conditions, for example through erosion of beaches

and coral bleaching, is expected to affect local resources, e.g., fisheries, and

reduce the value of these destinations for tourism.

Sea-level rise is expected to exacerbate inundation, storm surge, erosion

and other coastal hazards, thus threatening vital infrastructure, settlements

and facilities that support the livelihood of island communities.

Climate change is projected by mid-century to reduce water resources in

many small islands, e.g., in the Caribbean and Pacific, to the point where they

become insufficient to meet demand during low-rainfall periods.

With higher temperatures, increased invasion by non-native species is

expected to occur, particularly on mid- and high-altitude islands.

The consequences of these impacts will be greater because the Islanders are

Indigenous. It is widely recognised that Indigenous communities are much more

vulnerable to climate change because of the social and economic disadvantage

Indigenous communities already

face:[24]

Vulnerability to climate change can be exacerbated by the presence of other

stresses... vulnerable regions face multiple stresses that affect their exposure

and sensitivity as well as their capacity to adapt. These stresses arise from,

for example, current climate hazards, poverty and unequal access to resources,

food insecurity, trends in economic globalisation, conflict, and incidence of

diseases such as HIV/AIDS.[25]

Many of these stresses are found in the Torres Strait Islands’

communities. The Islands are remote, the Islanders do not have access to the

same services and infrastructure as other Australians and the health and other

social statistics of the Islanders are similar to other Indigenous Australians,

that is, they are significantly worse than non-indigenous Australians:

Social and economic disadvantage further reduces the capacity to adapt to

rapid environmental change, and so this problem is compounded on many of the

Islands which lack adequate infrastructure, health services and employment

opportunities.[26]

2 Climate change and the human rights of Torres

Strait Islanders

The predicted impact of climate change on the islands is severe. It threatens

the land itself and the existence of the Islands. The impacts predicted above

threaten the Islanders lives and their culture. If the serious predictions are

not headed, and no action is taken, the Torres Strait Islands will face a human

rights crisis.

In September 2007, the Interagency Support Group on Indigenous Issues pointed

out that:

the most advanced scientific research has concluded that changes in climate

will gravely harm the health of indigenous peoples’ traditional lands and

waters and that many of plants and animals upon which they depend for survival

will be threatened by the immediate impacts of climate

change.[27]

Yet to date, action on climate change has focused on environment and

conservation, and there has been little recognition of the need to protect

Indigenous peoples’ rights in the response to climate change. This must

change.

By ratifying various human rights instruments, Australia has agreed to respect, protect and fulfil the rights contained

within it.[28]

- The obligation to respect means Australia must refrain from

interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of human rights. - The obligation to protect requires Australia to protect individuals

and groups against human rights abuses – whether by private or government

actors. - The obligation to fulfil means that Australia must take positive

action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human

rights.[29]

Thus,

irrespective of the cause of a threat to human rights, Australia still

has positive obligations to use all the means within its disposal to uphold the

human rights affected.[30]

Chapter 4 of this Report outlines some of the threats that climate change

impacts pose to human rights generally. Some of the impacts that will be felt in

the Torres Strait Islands are discussed here.

2.1 The right to

life[31]

The right to life is protected in the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights (UDHR)[32] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights[33] (ICCPR). Article 3 of

the UDHR provides ‘everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of

person’. Article 6(1) of the ICCPR provides ‘every human being has

the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall

be arbitrarily deprived of his life’. The Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples[34] also

includes a right to life and security.

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – article 7

- Indigenous individuals have the rights to life, physical and mental

integrity, liberty and security of person. - Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace and

security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide

or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group

to another group.

In its General Comment on the right to life, the United Nations Human Rights

Committee warned against interpreting the right to life in a narrow or

restrictive manner. It stated that protection of this right requires the State

to take positive measures and that ‘it would be desirable for state

parties to take all possible measures to reduce infant mortality and to increase

life expectancy...’[35]

As articulated by the Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights, climate

change can have both direct and indirect impacts on human life. This is true for

the Torres Strait region, where the effect may be immediate; that is, as a

result of a climate-change induced extreme weather, a threat that has already

been felt when a young girl’s life was at risk in the 2006 king tides; or

it may occur gradually, through deterioration in health, diminished access to

safe drinking water and increased susceptibility to disease.

2.2 The right to

water[36]

The right to water is intricately related to the preservation of a number of

rights protected through the International Covenant on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights[37] (ICESCR). It underpins the right to health in article 12 and the right to

food in article 11. The right to water is also specifically articulated in

article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the

Child[38] (CRC), and article

14(2)(h) of the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against

Women[39] (CEDAW). Various

articles of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples refer to

rights to water for both cultural and economic uses.

In 2002, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognised

that water itself is an independent

right.[40] Drawing on a range of international treaties and declarations it stated,

‘the right to water clearly falls within the category of guarantees

essential for securing an adequate standard of living, particularly since it is

one of the most fundamental conditions for

survival’.[41] The same

General Comment refers specifically to the rights of Indigenous peoples to

water:

Whereas the right to water applies to everyone, States parties should give

special attention to those individuals and groups who have traditionally faced

difficulties in exercising this right...In particular, States parties should

take steps to ensure that:...(d) Aboriginal peoples’ access to water resources on their ancestral

lands is protected from encroachment and unlawful pollution. States should

provide resources for Aboriginal peoples to design, deliver and control their

access to water;’[42]

In the Torres Strait region, the right to water will be threatened by a

number of factors.

Both surface and ground water resources are likely to be impacted by climate

change making resource management in the dry season difficult. In the past, many

islands depended on fresh water lenses to provide drinking water, but

overexploitation of this resource has caused problems and created the need for

water desalination plants on many of the islands. Rainwater tanks and large

lined dams are now used to trap and store water for use in dry season. Many of

the islands have already reached the limits of drinking water supply and must

rely on mobile or permanent desalination plants to meet demand. Other problems

are likely to include an increase in extreme weather events such as droughts and

floods, and an increase in salt-water intrusion into fresh water

supplies.[43]

In addition, the rights that the right to water underpin, such as the right

to food and the right to life, will also be

threatened.[44]

2.3 The right to

food[45]

The right to adequate food is recognised in several international

instruments, most comprehensively in the ICESCR. Pursuant to article 11(1),

state parties recognise ‘the right of everyone to an adequate standard of

living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and

housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions’, while

article 11(2) recognises that more immediate and urgent steps may be needed to

ensure ‘the fundamental right to freedom from hunger and

malnutrition’. Article 20 of the Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples protects the right of Indigenous peoples to secure their

subsistence.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and develop their political,

economic and social systems or institutions, to be secure in the enjoyment of

their own means of subsistence and development, and to engage freely in all

their traditional and other economic activities. - Indigenous peoples deprived of their means of subsistence and development

are entitled to just and fair redress.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food has defined the right as

follows:

The right to adequate food is a human right, inherent in all people, to have

regular, permanent and unrestricted access, either directly or by means of

financial purchases, to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient

food corresponding to the cultural traditions of people to which the consumer

belongs, and which ensures a physical and mental, individual and collective

fulfilling and dignified life free of

fear.[46]

There is little doubt that climate change will detrimentally affect the right

to food in a significant way. In the Torres Strait, it is predicted that food

production will be severely affected because of increased temperatures, changing

rainfall patterns, salinity which will turn previously productive land

infertile, and erosion. Fishing, a major source of food for the region, will

also be affected by rising sea levels, making coastal land unusable, causing

fish species to migrate, and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather

events disrupting

agriculture.[47] Islanders have already identified a change a fish stocks, dugongs and turtles,

affecting their right to food that corresponds with their cultural traditions.

2.4 The right to

health[48]

Article 25 of the UDHR states that ‘everyone has the right to a

standard adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his

family’. Article 12(a) of the ICESCR recognises the right of everyone to

‘the enjoyment of the highest standard of physical and mental

health’. The right to health is also referred to in a number of articles

in the CRC. Article 24 stipulates that state parties must ensure that every

child enjoys the ‘highest attainable standard of health’. It

stipulates that every child has the right to facilities for the treatment of

illness and rehabilitation of health. Article 12 of the CEDAW contains similar

provisions.[49] Article 24 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples protects the right of

Indigenous peoples to health, their cultural health practices, and equality of

health services.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to

maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital

medicinal plants, animals and minerals. Indigenous individuals also have the

right to access, without any discrimination, to all social and health

services. - Indigenous individuals have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest

attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the

necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of

this right.

Many of these impacts are predicted to occur in the Torres Strait region.

Climate change will have many impacts on human health, and this threat is

even more prevalent for Indigenous peoples, who commonly don’t have access

to the same standard of health care that non-Indigenous Australians enjoy.

Additionally, the dietary health of [Indigenous] communities is predicted to

suffer as the plants and animals that make up our traditional diets could be at

risk of extinction through climate

change.[50]

Climate change may affect the intensity of a wide range of diseases –

vector-borne, water-borne and

respiratory.[51] Changes in

temperature and rainfall will make it harder to control dengue fever and other

diseases carried by mosquitoes, and there is a risk that the range and spread of

tropical diseases and pests will

increase.[52]

Increasing temperatures may lead to heat stress, while rising sea levels and

extreme weather events increases the potential for malnutrition and

impoverishment. This is particularly true for communities such as those in the

Torres Strait which rely on traditional harvest from the land and oceans, and

small crops.

However, in addition to the direct physical impacts on health, there are

health implications from disturbing Indigenous peoples’ connection to

country and their land and water management responsibilities:

Many Indigenous people living in remote areas have a heightened sensitivity

to ecosystem change due to the close connections that exist for them between the

health of their ‘country’, their physical and mental well-being and

the maintenance of their cultural practices. A biophysical change manifested in

a changing ecosystem has, for example, the potential to affect their mental

health in a way not usually considered in non-Indigenous

societies.[53]

The impact of climate change on the mental well-being of Torres Strait

Islanders has already been predicted:

The mental well-being of Islanders who feel that they can no longer predict

seasonal change is another factor that needs to be considered in any assessment

of Islander health. Given the close cultural connection between the natural

environment and Islander culture, habitat change that impacts significant fauna

(for example, reduction in turtle nesting beaches, migratory bird foraging or

sea grass bed decline) is likely to affect Islanders’ mental

well-being.[54]

2.5 The right to a healthy

environment[55]

In Australia, and elsewhere, there have been discussions about the existence

of an internationally recognised human right to an environment of a particular

quality. The Advisory Council of Jurists of the Asia-Pacific Forum on National

Human Rights Institutions endorsed the idea that the protection of the

environment is ‘a vital part of contemporary human rights doctrine and a sine qua non for numerous human rights, such as

the right to health and the right to

life’.[56]

The link between the environment and human rights has been the subject of

many ‘soft law’ instruments of international environmental

law.[57] This includes the first

international law instrument to recognise the right to a healthy environment,

the 1972 Stockholm Declaration on the Human

Environment.[58] Others

followed, including the 1992 Rio

Declaration[59] and the 1994

draft Declaration of Principles on Human Rights and the Environment which

‘demonstrates that accepted environmental and human rights principles

embody the right of everyone to a secure, healthy and ecologically sound

environment, and it articulates the environmental dimension of a wide range of

human rights.’[60]

Article 29 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples protects the right of Indigenous peoples to the conservation and protection of

the environment.

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – article 29

- Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the

environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and

resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for

indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without

discrimination. - States shall take effective measures to ensure that no storage or disposal

of hazardous materials shall take place in the lands or territories of

indigenous peoples without their free, prior and informed consent. - States shall also take effective measures to ensure, as needed, that

programmes for monitoring, maintaining and restoring the health of indigenous

peoples, as developed and implemented by the peoples affected by such materials,

are duly implemented.

There are domestic laws in Australia that are related to the protection of a

healthy environment. Chapters 4 and 5 of this report, outline some of these

mechanisms.

Relevant to the Torres Strait region is the Environmental Protection and

Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBCA) which was passed in

response to the International Convention on Biodiversity. The EPBCA provides a

legal framework to protect and manage matters of national and international

environmental significance and it aims to balance the protection of these

crucial environmental and cultural values with our society’s economic and

social needs.

There are significant concerns about the threats to biodiversity in the

Torres Strait. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has predicted a

significant loss of biodiversity in surrounding

regions.[61] Already, turtle nesting

failures and other impacts on biodiversity have been identified by Islanders.

Acting on this concern, the Torres Strait Regional Authority has recommended to

the government:

that there are further studies of island processes and projected climate

change impacts on island environments, including uninhabited islands with

problems such as turtle nesting

failures.[62]

2.6 The right to

culture[63]

While the focus of media and political debates in Australia presently rests

with the environmental and economic impacts of climate change, inextricably

linked to environmental damage is damage to Indigenous peoples cultural heritage

and identity. The devastation of sacred sites, burial places and hunting and

gathering spaces, not to mention a changing and eroding landscape, cause great

distress to Indigenous

peoples.[64]

Indigenous peoples across the world have a right to practice, protect and

revitalise their culture without interference from the state. Governments have

an obligation to promote and conserve cultural activities and

artefacts.[65] The right to culture

is entrenched in a number of international law instruments. Article 27 of the

ICCPR protects the rights of minorities to their own culture. The Human Rights

Committee’s General Comment 23 makes it clear that this right applies to

Indigenous peoples. The Committee also confirmed that this may require the

states to take positive legal measures to protect this

right.[66]

The right to culture is also found in a number of other instruments including

article 15 of the ICESCR which upholds the right of everyone to ‘take part

in cultural life’, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Racial Discrimination[67] (ICERD), commits all states to ‘ensure that indigenous communities can

exercise their rights to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and

customs and to preserve and to practise their

languages.’[68] The General

Comment to the ICERD also provides that ‘no decisions directly relating to

[Indigenous communities’] rights and interests are taken without their

informed consent.’[69]

Article 30 of the CRC protects the rights of children to their culture.

Article 8 of International Labour Organisation Convention 169 provides a

specific protection for indigenous peoples stating that: ‘[Indigenous

peoples] shall have the right to retain their own customs and institutions,

where these are not incompatible with fundamental rights defined by the national

legal system and with internationally recognized human

rights.’[70]

Importantly, under the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, Indigenous peoples have a number of rights related to the right to

practice and revitalisation of their cultural practices, customs and

institutions.[71]

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – various articles

Article 5

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct

political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining

their right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic,

social and cultural life of the State.

Article 8

- Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to

forced assimilation or destruction of their culture. - States shall provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress

for:- (a) Any action which has the aim or effect of depriving them of their

integrity as distinct peoples, or of their cultural values or ethnic

identities. - (b) Any action which has the aim or effect of dispossessing them of their

lands, territories or resources. - (c) Any form of forced population transfer which has the aim or effect of

violating or undermining any of their rights. - (d) Any form of forced assimilation or integration.

- (e) Any form of propaganda designed to promote or incite racial or ethnic

discrimination directed against them.

- (a) Any action which has the aim or effect of depriving them of their

Article 11

- Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural

traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop

the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as

archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies,

technologies and visual and performing arts and literature. - States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include

restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to

their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without

their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions

and customs.

Article 12

- Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach

their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to

maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural

sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the

right to the repatriation of their human remains. - States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial

objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and

effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples

concerned.

Article 25

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their

distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise

occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other

resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this

regard.

In 2000, the United Nations Human Rights Committee expressed concern about

Australia’s recognition of the cultural rights of its Indigenous

population:

The Committee expresses its concern that securing continuation and

sustainability of traditional forms of economy of indigenous minorities

(hunting, fishing, gathering), and protection of sites of religious or cultural

significance for such minorities, which must be protected under article 27, are

not always a major factor in determining land

use.[72]

This recognition could become even more limited with climate change, as there

is expected to be a significant threat to cultural rights as a result. One way

this will occur is through damage to the land, which in turn can damage cultural

integrity:

Indigenous people don't see the land as distinct from themselves in the same

way as maybe society in the south-east (of Australia) would. If they feel that

the ecosystem has changed it’s a mental anxiety to them. They feel like

they've lost control of their ‘country’ ― they're responsible

for looking after

it.[73]

In the Torres Strait Islands, the threats to culture from climate change are

already being felt; for example graveyard sites have already been threatened and

damaged by recent king tides, and the nesting behaviour of turtles has already

become unpredictable because of changing weather patterns and erosion. Many

aspects of Ailan Kastom are threatened if the predicted impacts of

climate change eventuate:

Islander culture, or Ailan Kastom, refers to a distinctive Torres

Strait Islander culture and way of life, incorporating traditional elements of

Islander belief and combining them with Christianity. This unique culture

permeates all aspects of island life...Ailan Kastom governs how Islanders

take responsibility for and manage particular areas of their land and sea

country; how and by whom natural resources are harvested, and allocation of

seasonal and age-specific restrictions on catching particular species. The

strong cultural, spiritual and social links between the people and the natural

resources of the sea reinforces the significance of the marine environment to

Islander culture. One major component of Ailan Kastom relates to the role

of turtle and dugong, which have great significance as totemic animals for many

Islanders.[74]

(a) Dispossession and relocation

The land and waters are such an integral part of Ailan Kastom, that

before native title law, one author wrote:

The Strait does not have to worry about custom; the society of Islanders

there remains axiomatic as long as they are in occupation of their ancestral

islands and are living off resources which, whatever the legality, are theirs by

customary right.[75]

Yet, if climate change predictions are accurate, some Islands in the region

may disappear completely, and others may lose large tracts of land (see page 302

of this Report for photos of sea level predictions for Masig Island). Because of

this, some Islanders will be dispossessed of their lands and be forced to

relocate, threatening the existence of Ailan Kastom.

An Islander from Saibai has said ‘But we will lose our identity as

Saibai people if we scatter. If we separate, there will be no more

Saibai’.[76] Another, the TSRA

chairman John Toshie Kris, has been quoted as saying that relocation has been

discussed as a last resort; however, he believes it can be avoided with the help

of government, but ‘at the moment, you cannot move these people, because

they are connected by blood and bone to their traditional

homes.’[77]

This outcome would be in breach of Australia’s international human

rights obligations that protect a right to culture. General comment 23 to the

ICERD explicitly deals with returning lands to Indigenous peoples:

The Committee especially calls upon State parties to recognise and protect

the rights of indigenous peoples to own, develop, control and use their communal

lands, territories and resources and, where they have been deprived of their

lands and territories traditionally owned or otherwise inhabited or used without

their free and informed consent, to take steps to return these lands and

territories. Only when this is for factual reasons not possible, the right to

restitution should be substituted by the right to just, fair and prompt

compensation. Such compensation should as far as possible take the form of lands

and territories.[78]

Article 10 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also

confirms that Indigenous peoples cannot be moved from their lands without having

given their free, prior and informed consent.

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – article 10

Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or

territories. No relocation shall take place without the free, prior and informed

consent of the indigenous peoples concerned and after agreement on just and fair

compensation and, where possible, with the option of return.

The history of dispossession of the Indigenous peoples of Australia has

resulted in various state, territory and federal laws being passed in recent

years with an intention of making reparation for

dispossession.[79] However, if any

Islanders are relocated and dispossessed of their lands, it will not only affect

their culture, but it will impact on their existing legal rights to the land,

and potentially the legal rights of other Indigenous people. All of these

impacts must be considered by government.

(b) Native Title

As I noted at the beginning of this chapter, the Torres Strait Islands are

the birthplace of native title law. All inhabited islands in the region, and

some uninhabited islands have native title rights determined over them. Other

uninhabited islands and the surrounding sea have native title claims over them,

but are yet to be determined. However, with the impacts of climate change

predicted above, those hard won native title rights may be lost.

Erosion and the threat of extreme weather events including king tides have

already damaged and ruined sites that have native title rights and interests

determined over them. It has also already forced some to move off the lands that

they have native title determined over, onto higher ground.

The possibility of native title being extinguished by climate change raises

questions about what remedies the Islanders might be able to seek if this

occurs. This is discussed later in this chapter.

(c) Relocation

The Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) adopted National Climate

Change Adaptation Framework (the Framework) states that a potential area of

action is to ‘identify vulnerable coastal areas and apply appropriate

planning policies, including ensuring the availability of land, where possible,

for migration of coastal

ecosystems.’[80] The Framework

discusses the expected need for Islanders to migrate to the mainland or urban

centres.

Currently, the discussion about intra-Australia relocation has focused on

relocation as a predominantly economic issue with social implications,

particularly the resulting strain on infrastructure.

However, culture and cultural practices will have implications on the social

and economic dimensions of relocation, something which has not been acknowledged

by the federal government. But ‘[s]ocial conflicts stemming from

ecological changes are not easily

resolved’.[81]

For Torres Strait Islanders, there are two possible relocations that may

occur, depending on what impacts of climate change eventuate.

Firstly, some Islanders may be forced to move onto higher land on their

island or another Torres Strait Island. Some have already started to negotiate

such a move, and some families have already made agreements with another family

that when the impact of erosion gets too bad, they can move onto the

other’s land.[82] However this

is not guaranteed.

Well on Murray Island what we’ll do is go up the hill a bit further.

The only thing we’ll have to do is every Island community is owned by a

particular family or clan; so for argument’s sake, if I need to move

because I live down the bottom, I’d have to start negotiating with another

family or clan to move into their area. If they refuse, I’d have to go

back down.[83]

Secondly, Islanders may be forced to move onto the mainland. This would

probably mean moving to the Cape York region – closest to their homes and

where some of their relatives may now

reside.[84] However, this is land

that traditionally belongs to the Aboriginal people of that area, and some of

that land has in fact been handed back to the Traditional Owners by the

Queensland government. Some has also had native title determined over it.

Relocation to the mainland occurred in the 1940s, when in response to a

flood, some Islanders decided to move. However:

This relocation, however, did not take account of the potential cultural

sensitivities of moving Islander people on to what is now recognised as

Aboriginal land. These concerns would need to be at the forefront of any

relocation negotiations in the future (Jensen Warusam pers. comm.

2006).[85]

The impacts of such a move on the land rights and cultural rights of

Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, is a serious issue that the

government must factor in to its decision making on climate change adaptation.

It is a complicating factor, as one Islander put it:

...if there’s an influx of a thousand people settling in Cairns or

somewhere, it’s going to cause a lot of major

problems.[86]

3 What is already being done?

Recognising the impacts of climate change that are already being felt in the

region, and the vulnerable position that the Islanders are in, a number of

initiatives have begun. However, many of these projects are in their initial

stages and need to be supported, improved and complemented so that the potential

human rights crisis in the Torres Strait is averted. The primary state, regional

and federal responses to climate change in the Torres Strait are listed below.

3.1 The Torres Strait Coastal Management

Committee[87]

The Torres Strait Coastal Management Committee (the Committee) was

established by TSRA in 2006 to enable a whole-of-government coordinated response

to coastal issues in the Torres Strait. It consists of representatives from the

Queensland government, the islands, and recently it has included a federal

government representative. It coordinates and oversees a range of projects that

were initially developed to deal solely with coastal care. However, in

recognition of the link between coast care and the predicted significant impacts

of climate change, the Committee’s work has recently expanded to include

projects dealing with climate change. Some projects include:

- Investigation of sea erosion affecting communities and solution

development - Sea level survey and land datum corrections

- Sustainable land use planning

- Climate impacts in the Torres Strait, and incorporation of traditional

environmental knowledge - Development of a climate change strategy for the Torres Strait

- A survey to develop high level resolution digital evaluation model for low

lying areas to assist in planning for sea level rise and storm tide

inundation.[88]

The

Committee actively involves island communities in decision making and project

activities[89] and considers

community support for any action to be vital.

One of the projects the committee has established is the Coastal Erosion

Project. It too has been developed and expanded to deal with climate change

impacts on erosion through inundation and extreme weather events.

(a) Coastal Erosion Project: Masig, Warraber,

Poruma, Iama

In December 2005, the Natural Heritage Trust approved funding for a Coastal

Erosion Impacts Project in the Torres Strait to be undertaken by James Cook

University with the communities of Warraber, Masig and Poruma Islands. The

project, which commenced in April 2006, was extended to include lama Island, and

is due to be finalised in very near future. [90]

The long term outcome that the project is seeking is management of erosion on

the cay islands, which are the lowest lying islands in the Torres

Strait.[91] In order to achieve

this, the project aims to:[92]

- Work with communities to identify and prioritise threats. The project has a

strong focus on community participation and decision making and it

‘engage[s] the community to understand the cultural and social aspects of

the problem and determine what it most important to the

community’.[93] - Identify the underlying causes of coastal erosion on Torres Strait reef

islands, and to develop long-term, sustainable solutions that work with, rather

than against, the natural processes. - To provide real data about the processes involved and the way in which

solutions may address these, these can be used to develop strong funding

applications for appropriate works.

At the conclusion of the

project, the community is to decide a suitable long-term response to the

problem.

(i) Masig’s

response[94]

To date, the only island that has made a decision about how they will adapt

to erosion is Masig Island. Masig will be severely affected by climate change if

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sea level rise predictions occurs.

This will include inundation of most of the inhabited areas of the island (see

photos of Masig Island on page 301 of this Report).

With the assistance of the coastal erosion project, the Masig community has

made some decisions about their future and how they want to progress an

adaptation strategy.

The people of Masig reaffirm that they wish to continue to live on Masig into

the future. The people of Masig understand that much of the island (and in

particular the area around the village) is low, and that flooding events may

become more regular and more significant in the future due to climate change.

However, it is also understood that flooding will only happen occasionally, on

the highest tides and when weather conditions are unfavourable, at least for the

foreseeable future.- The people of Masig are prepared to participate in a process of adaptation

to environmental and climate change which may include things such as:

- As houses or other infrastructure reaches the end of its usable life, not

rebuilding in the same place if that place may be subjected to erosion or

inundation due to rising sea levels- Not building new infrastructure in hazardous locations unless absolutely

essential.- Over time, moving the focus of the island village towards higher parts of

the island- Managing boeywadh (berms) with the intention of building them higher and

wider, and managing access tracks through them to ensure that water cannot enter

the island interior- Allowing some parts of the island to erode, where that erosion is not

causing harm to people, infrastructure or important cultural sites, while

monitoring the situation.- The Masig community recognises that adaptation will raise issues that must

be addressed within the community, such as land ownership and traditional

rights, and the community is willing to work through these issues.- The community wants to further explore the possibility of dredging

off-reef sand to renourish the island beaches.- The community is willing to be involved in the testing of innovative

solutions to coastal erosion, where appropriate.- The community will do the important things that they can, such as

implementing management plans for the buoywadh and coastal vegetation.- The community is willing to work with government at all levels,

researchers and infrastructure providers to make a case to obtain funds to

progress these measures, and to make decisions when options are put before the

community.[95]

The

project must continue to be supported so that it can be implemented in its

entirety. In addition, further strategies will be needed to complement these

activities which primarily deal with only one aspect of climate change.

3.2 A federal study: climate change for northern

Indigenous communities

The Australian Government is funding a study on ‘how climate change

will impact on Indigenous communities in northern Australia’. For the

purpose of the study, northern Australia includes the Torres Strait region. In

announcing the initiative, the Minister for Climate Change and Water recognised

that the Government has ‘limited understanding of how climate change will

affect Indigenous communities, their resilience and their capacity to

adapt.’ Positively, the study will take a more holistic approach than most

climate change policy to date, and will examine the impacts on health, the

environment, infrastructure, education, employment and opportunities that may

arise from climate change. The study, which should be completed by April 2009,

will enable the Government to determine what action needs to be taken to reduce

the impact of climate change in the

region.[96]

4 What next?

The Australian Human Rights Commission has outlined what a human rights based

response to climate change must involve:

[A] human rights-based approach...should focus on poverty-reduction,

strengthening communities from the bottom up, building on their own coping

strategies to live with climate change and empowering them to participate in the

development of climate change policies. It needs to be locally grounded and

culturally appropriate...the human rights-based approach...emphasises the

importance of local knowledge and seeks the active participation and

consultation of local communities in working out how best to adapt to climate

change. This could mean, for example, incorporating the traditional cultural

practices of indigenous communities into climate change

responses.[97]

Such an approach is being followed by the Coastal Erosion Project, where the

ultimate decision makers are the communities. If the power to make decisions is

taken away from communities, the project would lose legitimacy and run the risk

of failure:

Decisions made without consultation of Indigenous communities can force

unwelcome lifestyle changes for them. Westerners don’t listen to worries

about land—but we want natural protection from climate change that

doesn’t conflict with traditional ways of

life.[98]

A human rights based approach to climate change can easily be integrated into

the various stages of ‘adaption as a process’ identified by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The adaptation process

includes:[99]

- knowledge, data, tools

- risk assessments

- mainstreaming adaptation in to plans, policies, strategist

- evaluation and monitoring for feedback and change

- awareness and capacity building

All of these areas have been

identified as lacking in the Torres Strait where improving knowledge,

information, risk assessment, planning, and capacity building, have all been

identified as urgent priorities.

4.1 Information, knowledge, data

The lack of data and information on climate change impacts in the Torres

Strait region has been acknowledged by many parties.

The TSRA, CSIRO and Queensland government submissions to House of

Representatives Standing Committee Inquiry into climate change and environmental

impacts on coastal communities both identified a lack of data as an issue. In

response, the Queensland government is undertaking some projects in the Torres

Strait Islands such as the Tide Gauge Project:

Tidal data for the Torres Strait Islands region is insufficiently accurate to

manage and respond to events such as storm surge and projected sea level rise.

The project will provide accurate data to inform such activities as storm surge

and sea-level rise mapping for the

Islands.[100]

This lack of information is not unique to the Torres Strait. The COAG adopted

National Climate Change Adaptation Framework identifies the lack of information

and knowledge gaps as integral to the two priority areas for potential action.

However, the timeframe for implementing the framework is up to seven years.

It is an urgent priority in the Torres Strait. The TSRA, in its submission,

has identified the lack of local data and science as a major impediment to their

planning and projects to deal with climate change. It has proposed that the

Australian Government fund long term monitoring of sea levels through the

installation of gauges and mapping, which could contribute to an inundation

warning system. It has also proposed that the Government undertake specific

regional scale modelling of changes to climate, which hasn’t been

undertaken in the Torres Strait to

date.[101]

One aspect of remedying this problem, which is consistent with a human rights

based response to climate change, is recognising and utilising traditional

environmental knowledge, which has already been identified by natural scientists

as an under-used resource for climate impact and adaptation assessment.

Recognition is slowly beginning to grow of the untapped resource of Indigenous

knowledge about past climate change in Australian and internationally, which

could be used to inform adaptation

options.[102] However, as chapter

7 highlights, it is important that the legal ownership of this knowledge remains

with its true owners.

4.2 Governance, planning and strategies

It is integral that agencies’ roles, responsibilities and

accountability for governance of climate change issues in the Torres Strait

Islands is clear.

There are unique characteristics of the Torres Strait region that make this

particularly important. There are complex international border issues with Papua

New Guinea, and the area is governed by an international treaty. The Torres

Strait Regional Authority, the Torres Strait Regional Islands Council, the

Queensland Government and the Commonwealth all have some jurisdiction over the

governance of the region. Within each of these there are additional layers of

complexity about which portfolio is responsible for what. For example, there are

22 Queensland government agencies responsible for carrying out the actions

outlined in the State’s ClimateSmart Adaptation plan over the next

5 years.[103] Further, there are

numerous Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) operating in the region, who are

eager to play a role in supporting the Islanders to mitigate and adapt to

climate change impacts

The CSIRO has highlighted the need for clear governance responsibilities in

order for climate change responses to be effective:

Coastal governance should seek to maintain a flow of multiple values from

multiple natural and built assets, across several scales, to diverse

stakeholders, including future generations... each coastal region faces

different challenges and opportunities from climate change. Meanwhile,

overlapping, unclear or juxtaposed jurisdictions across local, state and

Commonwealth governments do hamper integrated and coordinated

responses.[104]

In its submission to the House of Representatives Committee, the CSIRO noted

the need for governance and decisions to be made at the right

scale.[105] Consistent with the

human rights based approach outlined above, the governance of climate change

issues should primarily involve clear decision making responsibilities and

powers that rest with the community.

4.3 Evaluation and monitoring

At the moment there are only a small number of projects being undertaken in

the Torres Strait, but it is important to ensure that all projects that are

undertaken include evaluation and monitoring in their design. Consistent with

the human rights based approach, this monitoring and evaluation should be done

with particular emphasis on the Islanders themselves identifying the impacts

that climate change, and the projects undertaken, are having on their lives. The

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues recommends:

Monitor and report on impacts of climate change on indigenous peoples,

mindful of their socio-economic limitations as well as their spiritual and

cultural attachment to lands and

waters.[106]

4.4 Awareness and capacity building

Any information or data that is available must be distributed to the

communities so that they can engage in the decision making process.

Our duty as Indigenous peoples to Mother Earth impels us to demand that we be

provided adequate opportunity to participate fully and actively at all levels of

local, national, regional and international decision-making processes and

mechanisms in climate

change.[107]

The CSIRO considers that successful adaptation requires investment in

leadership, skills, knowledge, and adaptable infrastructure so that communities

can self organise and respond quickly and

effectively.[108]

To ensure this can occur, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous

Issues recommended that all states ensure Indigenous peoples are well resourced

and supported to make those decisions including through providing policy

support, technical assistance, funding and

capacity-building.[109]

Text Box 2: TSRA recommendations

The TSRA has made the following recommendations to the House of

Representatives Standing Committee Inquiry into climate change and environmental

impacts on coastal

communities.[110]

Recommendation 1: That there is further support for all Torres

Strait Island communities and regional institutions to access information about

projected climate change impacts at a locally and regionally relevant scale, to

enable informed decision making and adaptive planning.

Recommendation 2: That there are further studies of island processes

and projected climate change impacts on island environments, including

uninhabited islands with problems such as turtle nesting failures.

Recommendation 3: That reliable data is obtained on island interior

heights and elevations to support more accurate predictions of inundation

levels.

Recommendation 4: That a feasibility study be undertaken to

investigate and recommend the most suitable renewable energy systems for

servicing the Torres Strait region, including the investigation of tidal, wind,

solar and other systems suitable for the region's environmental conditions and

demand for power.

Recommendation 5: That the Torres Strait region is considered as a

potential case study for small scale trials of solutions to coastal erosion and

inundation problems, as well as sustainable housing and building design and

construction for remote communities in tropical environments.

TSRA proposal to address coastal management and climate change issues in

the Torres Strait:[111]

The proposal details a comprehensive approach to investigate, monitor and

plan for adaptation to climate change. It covers:

- Basic data collection and monitoring , including a tide gauge network,

accurate bathymetry (targeted nearshore surveys) and topographic mapping - Climate science (eg detailed modelling of regional sea level rise, winds,

waves, storm surge, water chemistry etc) to determine changes to key regional

climate variables. - Island process modelling/ impact assessment - to determine impacts of

coastal hazards and climate change on an island by island basis. - Dredge feasibility study - A feasibility study to examine the potential for

dredging for harbour maintenance and possibly beach renourishment or sand

placement to address sea level rise. - Adaptation planning - to determine the best suite of adaptation measures to

address impacts of coastal hazards and climate change at the community level.

(This would build on current projects and address the islands that have yet to

be included and more fully address climate change issues - particularly sea

level rise at Boigu and Saibai). - Identification of sustainable energy options suitable for Torres Strait and

ways of encouraging more sustainable practices in the region. - Implementation of adaptation plans. Potential options/ works/ costs to

address sea level rise/ inundation.

5 If things continue as they are? Torres Strait

Islanders rights of action

Less than twenty years ago Australian law did not recognise Torres Strait

Islanders’ rights to their land. But the Islanders fought for their rights

through the courts and won. However, ‘[t]oday it is the sea, not the law,

that is taking their

land’[112], and the

Islanders may once again want to consider how the law can be used to enforce

their rights if government action is inadequate.

Internationally, communities are testing domestic and international legal

frameworks in an attempt to protect themselves from the impacts of climate

change.

Climate-related litigation is a reality, particularly in the United States

where action has been taken against private companies, administrative decisions

and government agencies...In relation to the impacts on Indigenous peoples, in

February 2008 the Alaskan native village of Kivalina filed a lawsuit against a

number of oil, coal and power companies for their contribution to global warming

and the impacts on homes and country disappearing into the Chukchi Sea. The

village is facing relocation due to sea erosion and deteriorating coast. The

Kivalina seek monetary damages for the defendants. Past and ongoing

contributions to global warming, public nuisance and damages caused by certain

defendants, acts in conspiring to suppress the awareness of the link between

their emissions and global warming...Based on examples from the United States,

there may be scope for litigation outside administrative review in Australia.

Other possible climate related legal action may exist in negligence or nuisance.

Indigenous people do and will continue to suffer loss, damage and substantial

interference with their use or enjoyment of country as a result of climate

change.[113]

There are currently no laws in Australia that deal specifically with

protecting people from climate change

impacts[114] but there may be

other laws the Islanders can use to seek a remedy. Some of those possibilities

are explored here.

5.1 Environmental Protection Act 1994

(Qld)

In Queensland, the principal law dealing with environment protection is the Environment Protection Act 1994 (Qld) (EPA). The object of the EPA is to

‘protect Queensland’s environment while allowing for development

that improves the total quality of life, both now and in the future, in a way

that maintains the ecological processes on which life depends’, that is,

‘ecologically sustainable

development’.[115] It

includes an offence of causing serious or material environmental harm.

The notion of ‘environmental harm’ is widely defined, with people

and culture being recognised as an integral part of ‘environment’

under the legislation and, although it has not been judicially tested, could

foreseeably encompass the emission of greenhouse gases and consequential climate

change.

One of the benefits of the Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Qld) is

that it does not require a particular power station to be the sole cause

of climate change, which is caused by many contributing factors. The benefit of

this type of action is that a court could potentially order the power station to

pay for the cost of repairs to infrastructure caused by storms or even the costs

of relocating homes and people. One of the difficulties in bringing such an

action is that the power station might present a number of arguments in

response, including that it had all the necessary

approvals.[116]

5.2 Negligence

The tort of negligence essentially considers whether there has been a failure

to take reasonable care to prevent injury to others. There is some potential to

argue that various local, state and commonwealth authorities have failed in

their duty of care to protect Torres Strait Islander communities from the

impacts of climate change and are therefore liable for the damage to those

communities.[117] It may be

difficult for the Islanders to prove a duty of care, but if one could be

established, it may be possible to apply such an argument to large emitters of

greenhouse gas emissions. However, the greatest obstacle will be proving who has

caused the injury.

5.3 Public

nuisance[118]

The tort of public nuisance focuses on an interference with the right to use

and enjoy land. Public nuisance is defined as an unlawful act, the effect of

which is to endanger the life, health, property, or comfort of the public.

Public nuisance must affect the public at large.

It is not a defence to a nuisance action based on pollution for the polluter

to prove that the environment was already polluted from another source or that

the polluter’s individual actions were not the sole cause of the

nuisance.[119] This may mean that

public nuisance is better suited to climate change actions than negligence

because causation issues are likely to be less complex. However, if all

polluters were acting legally, then the action may fail.

5.4 Human Rights Remedies

Although the Australian Government may have no obligations to Pacific and

Indian islanders and other non-Australians under human rights law, because it

has ratified and implemented all the major human rights treaties it does already

have human rights obligations towards its own citizens...[120]

This chapter has laid out a number of the human rights implications of

climate change on the lives of Torres Strait Islanders. It threatens their

lives, health, food, water and culture among others. Without a federal or

Queensland charter of human rights, there are only a few human rights mechanisms

that the Islanders could pursue. However, in summary ‘Australia’s

current human rights laws do not provide adequate protection to Torres Strait

Islanders faced with damage to their culture and possible relocation as a result

of climate change’.[121]

(a) Native title

The Native Title Act is intended to protect and recognise native

title.[122] As I’ve already

stated, all the inhabited islands in the Torres Strait have had native title

rights and interests determined over them, and under the Act, those native title

rights cannot be extinguished contrary to

it.[123]

Yet, one of the real risks posed by climate change is that those native

rights and interests will be lost as a result of climate change – through

damage or complete loss of particular sites and land. So how can the NTA protect

the native title rights and interests of the Torres Strait Islanders’? Is

sea level rise an ‘act’ in the sense contemplated by and protected

under the Act?[124]

Section 226 of the NTA defines ‘acts that affect native title’ to

include not only positive acts such as the making of legislation or granting of

a licence, but the ‘creation, variation, extension, renewal or

extinguishment of any interest in relation to land or waters’. Sea level

rises will extinguish certain rights and interests over land because they will

disappear. The question will be whether the flooding of land will be interpreted

as an ‘act’ despite the fact that the cause of that rise is

essentially inaction on the part of governments to protect native title

interests by taking steps to prevent climate change. Under section 227, such an

act will ‘affect’ native title as it is wholly or partly

inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of native title

rights and interests.

The NTA regulates activities or developments that may ‘affect’

native title rights. These acts are known as ‘future acts’.

Government inaction to prevent the impact of climate change on the Torres Strait

Islands could constitute a ‘future act’. In addition, those persons

or companies who are taking actions that contribute to global warming and hence

impacts on sea levels and native title rights in due course may also be

undertaking ‘future acts’ which require different procedures in the

NTA to be complied with. At present, the requirements of the future acts

provisions in the NTA, such as notifying Traditional Owners, are not being

undertaken by any of these parties. If this line of argument can be proven, the

acts would be invalid under s 24OA of the NTA.

The NTA provides various circumstances in which native title holders may be

eligible to receive compensation for acts which have impaired their native title

rights or would have otherwise been

invalid.[125] It could be argued

that the failure to take steps to mitigate climate change means that the

Commonwealth and Queensland governments in particular have contributed to the

extinguishment of native title rights and they are liable to pay compensation.

As I reported in my Native Title Report 2007, there have been no

successful claims for compensation under the

NTA.[126] This is partly because

native title must be proved before an application for compensation can be

successful, and as my native title reports show, native title is extraordinarily

difficult to prove. However, native title has already been proven and determined

in much of the Torres Strait. The compensation they could claim would be based

on market value plus any amount to reflect the cultural value of the land, and

could be of significant value. It won’t, however, keep their land above

water.

(b) International human rights law

In 2005, the Inuit (the Indigenous inhabitants of the Arctic region of North

America and Greenland) brought a petition to the Inter American Commission of

Human Rights[127] requesting its

assistance in obtaining relief from human rights violations resulting from the

impacts of climate change caused by the acts and omissions of the United States.

In particular, the petition argued that the US had violated a number of rights

set out in the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, the

ICCPR, and the ICESCR.

Similar to the impacts expected in the Torres Strait, climate change is, and

will continue to, impact on the Inuit people’s rights under international

human rights law.

However, unlike the Americas, Australia does not have a regional human rights

body. Nonetheless, it is possible that Torres Strait Islanders could bring their

complaints to United Nations bodies. In particular, the United Nations Human

Rights Committee can receive individual complaints of violation of rights under

the ICCPR, and actively investigate and rule upon

them.[128] While the Human Rights

Committee cannot make binding decisions, its recommendations can highlight the

problem and put pressure on the government to act.

6 Conclusion

I have written this brief chapter to highlight the breadth and seriousness of

the potential consequences of climate change on the human rights of one of

Australia’s Indigenous populations – the Torres Strait Islanders.

The possible challenges the Islanders will face in the coming years are

overwhelming and potentially devastating.

In order to avoid a human rights crisis, the Australian Government must

respond immediately.

It’s been said to me by some Islanders that they’re very happy

that the Australian government is investing in the Pacific, to help their

brothers and sisters deal with the impact of climate change. But they wonder why

they government is not more strongly investing in similar communities in

Australia, and they feel a bit

overlooked.[129]

The Islanders are seeking attention and support from government, and are

committed to working with all layers of government to protect and ensure their

future. In one of my discussions, James Akee, an islander from Mer, invited

Senator the Hon Penny Wong, Minister for Climate Change and Water, and The Hon

Kevin Rudd MP, Prime Minister to the island to see for themselves the difficult

situation they face.[130] However,

if that assistance, guidance and support is not forthcoming, then the

consequences for the Islanders, and the rest of Australia could be very grim.

It is hoped that the progress toward a carbon-constrained future involves

collaboration and opportunity as opposed to litigation. However the pathway will

no doubt be shaped by the action or inaction of government and the private

sector...The alternative, if this relationship further deteriorates, lies in

litigation for loss and damage of lifestyle, identity, sacred places, cultural

heritage and impairment of human rights and native title rights and interests.

Investment in relationships is, in effect, an investment in mitigating the

ecological, economic and human risks associated with climate

change.[131]

Climate change and the human rights of Torres Strait Islanders

Iama Island after the king tide in February

2006[132]

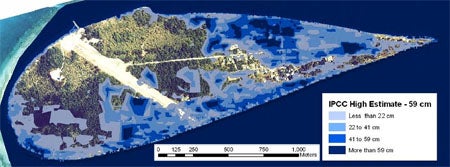

Masig Island

Masig Island: highest tides

now[133]

Masig Island: IPCC high tide estimate for

2100[134]

[1] Avaaz, ‘Avaaz

petition’, Email to the Australian Human Rights Commission, 3

September 2008.

[2] Australian

Bureau of Statistics, Population Distribution, Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Australians 2006, 4705.0. At: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4705.02006?OpenDocument (viewed September 2008).

[3] See www.tsra.gov.au. There are also two large