Chapter 4: Cultural safety and security: Tools to address lateral violence - Social Justice Report 2011

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Social Justice Report 2011

Chapter 4: Cultural

safety and security: Tools to address lateral violence

- Chapter 1: The Year in Review

- Chapter 2: Lateral violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

- Chapter 3: A human rights-based approach to lateral violence

- Chapter 4: Cultural safety and security: Tools to address lateral violence

4.1 Introduction

Lateral violence is a multilayered, complex problem and because of this our

strategies also need to be pitched at different levels. In Chapter 3 I have

looked at the big picture, with the human rights framework as our overarching

response to lateral violence. In this Chapter I will be taking our strategies to

an even more practical level, looking at how we can create environments of

cultural safety and security to address lateral violence.

A culturally safe and secure environment is one where our people feel safe

and draw strength in their identity, culture and community. Lateral violence on

the other hand, undermines and attacks identity, culture and community. In this

Chapter I will be looking at ways to establish an environment that ensures:

- cultural safety within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and

organisations - cultural security by external parties such as governments, industry and

non-government organisations (NGOs) who engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities and organisations.

The concepts of cultural

safety and security are illustrated through a selection of case studies

highlighting promising practices that are occurring both within our communities

and in partnership with government. These case studies provide us with practical

strategies, but just as importantly, they also remind us that our communities,

with the right support, have the ability to solve their own problems. This gives

me hope that we can begin to address the problems of lateral violence.

4.2 Defining cultural

safety and cultural security

As we saw in defining lateral violence in Chapter 2, there are a variety of

words that are used to describe lateral violence. Similarly, there is some

debate in the literature around the differing concepts of cultural safety and

security. I will explain this briefly below.

While I do not want to get bogged down in semantics, I think that the

concepts of cultural safety and cultural security both add something to the way

we think about addressing lateral violence. Cultural safety encapsulates the

relationships that we need to foster in our communities, as well as the need for

cultural renewal and revitalisation. The creation of cultural safety in our

communities will be the focus of the case studies in the next part of this

Chapter.

Cultural security on the other hand, speaks more to the obligations of those

working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to ensure that

there are policies and practices in place so that all interactions adequately

meet cultural needs.

Whatever words you use, cultural safety and security requires the creation

of:

- environments of cultural resilience within Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities - cultural competency by those who engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities.

In other words, we need to bullet proof our

communities so they are protected from the weaponry of lateral violence. And

governments and other third parties need to ensure that our group cohesion does

not become collateral damage when they engage with our communities.

(a) Cultural

safety

The concept of cultural safety is drawn from the work of Maori nurses in New

Zealand and can be defined as:

[A]n environment that is safe for people: where there is no assault,

challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. It is

about shared respect, shared meaning, shared knowledge and experience of

learning, living and working together with dignity and truly

listening.[1]

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples a culturally safe

environment is one where we feel safe and secure in our identity, culture and

community. According to the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) the

concept of cultural safety:

[I]s used in the context of promoting mainstream environments which are

culturally competent. But there is also a need to ensure that Aboriginal

community environments are also culturally safe and promote the strengthening of

culture.[2]

VACCA is a leader in advancing the concept of cultural safety. Their research

into cultural safety and its relevance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

is considered in Text Box 4.1.

| Text Box 4.1: Exploring cultural safety |

|

Some examples of cultural safety included:

When asked if non-Indigenous environments created safety some responses

When asked

When asked about how a culturally safe place could help the community

|

The idea of cultural safety envisages a place or a process that enables a

community to debate, to grapple and ultimately resolve the contemporary causes

of lateral violence without fear or

coercion.[8]

VACCA conceives of cultural safety as re-claiming cultural norms and creating

environments where Aboriginal people transition; first from victimhood to

survivors of oppression, through to seeing themselves and their communities as

achievers and contributors.[9] Through

this transition Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can reclaim their

culture. Noel Pearson warns that without this reclamation:

Cultural and linguist decline between generations hollows out a people

– like having one’s viscera removed under local anaesthetic –

leaving the people conscious that great riches are being lost and replaced with

emptiness.[10]

Lateral violence fills the empty void. On the other hand, revitalising and

renewing our culture and cultural norms within our communities brings resilience

and can prevent lateral violence taking its place.

(b) Cultural

security

Cultural security is subtly different from cultural safety and imposes a

stronger obligation on those that work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples to move beyond ‘cultural awareness’ to actively

ensuring that cultural needs are met for individuals. This means cultural needs

are included in policies and practices so that all Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders have access to this level of service, not just in pockets where there

are particularly culturally competent workers.

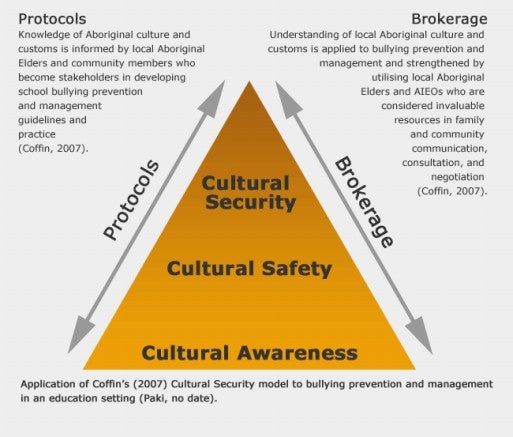

The cultural security model developed by Juli Coffin is outlined in Text Box

4.2.

| Text Box 4.2: Cultural security model[11] |

|

This model distinguishes between cultural awareness, cultural safety and Coffin uses a practical example of the management of an 8 year old

Farrelly and Lumby note how this model extends cultural competency well Cultural Security is built from the acknowledgement that theoretical |

A culturally secure environment cannot exist where external forces define and

control cultural identities. The role for government and other third parties in

creating cultural safety is ensuring that our voices are heard and respected in

relation to our community challenges, aspirations and

identities.[14] In this way cultural

security is about government and third parties working with us to create an

environment for a community to ‘exert ownership of

ourselves’.[15] Through this

ownership we are empowered.

4.3 Cultural

safety in our communities

The first part of this Chapter has looked at the concepts of cultural safety

and security. In this part I will be looking to the community level to celebrate

some of the approaches that are already making a difference in addressing

lateral violence on the ground. This approach is deliberate; you have to

understand the ‘why’, that is, have a big picture view of a problem

and solutions, before you can go about the ‘how’ of implementing a

response.

However, I also believe that communities inherently hold the best solutions

to their own problems. This is the strengths-based approach that I am always

advocating. This approach builds up our communities rather than constantly

tearing them down. At its core is empowerment.

The wisdom, resilience and ingenuity of those working with our communities is

always inspiring to me. This sentiment is shared by Lowitja

O’Donoghue:

So many good things are happening in our communities. We are kicking goals,

opening doors and breaking through the glass and brown ceilings. And, yet, the

times when we wholeheartedly and unanimously celebrate these achievements are

relatively few.[16]

These case studies are an opportunity to give some recognition to communities

and organisations that are innovating in the field of lateral violence.

But it is also more than an exercise in celebration and recognition. In the

absence of formal research and evaluation, these sorts of case studies provide

the best available way to look at what is working and why, providing valuable

lessons that can be relevant to other communities and contexts.

Again, like Chapter 2, this is not an exhaustive compilation of case studies

but it does provide a flavour of the richness of responses to lateral violence

that are already operating at the community level. Case studies will illustrate

responses to lateral violence in the contexts of education and awareness,

bullying, alternative dispute resolution and social and emotional wellbeing.

What all of these case studies have in common is their strong focus on creating

culturally safe places to confront and/or prevent lateral violence.

(a) Naming

lateral violence

Naming lateral violence is the first step towards exerting control over it.

It is also a way of exercising agency and responsibility for our communities.

Naming lateral violence becomes an action of prevention.

As I have said in Chapter 2, we know that the conversation around lateral

violence is not an easy one. It means confronting those in our communities who

perpetrate lateral violence and holding them accountable for their actions. But

facing up to tough issues is not new for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities. There are many instances of communities confronting problems like

family violence or alcohol abuse with great courage.

Naming lateral violence is essentially a process of awareness-raising and

education. It is about giving communities:

- the language to name laterally violent behaviour

- the space to discuss its impact

- the tools to start developing solutions.

The following case

studies highlight some of the emerging work in this area. Again, it is not a

definitive list but it highlights how different communities and organisations

have begun working in this area.

(i) Partnership between Native Counselling Services

of Alberta and the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health

I was first exposed to the concept of lateral violence in my previous role at

the Co-operative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (CRCAH). I attended the

Healing Our Spirit Worldwide movement held in Canada in 2006. The gathering was

hosted by the Native Counselling Services of Alberta (NCSA). At this gathering I

saw how much the concept of lateral violence resonated with Indigenous peoples

from around the world. I’ve seen first-hand how powerful these sorts of

workshops on lateral violence can be.

Since 2006 Allen Benson and Patti La Boucane-Benson from the NCSA have

delivered lateral violence workshops at numerous events, conferences and

organisations in Australia including the Garma Festival, the National Indigenous

Health Awards, Menzies School of Health Research, the Victorian Aboriginal

Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO) and the Southern Cross

University.

The CRCAH developed a close relationship with NCSA and they have jointly

presented on lateral violence on several occasions in Australia. To the best of

my knowledge these workshops were the first time that the concept was introduced

to Australia in a formal way and have kick started many conversations in our

communities.

The CRCAH made lateral violence a research priority. A lateral violence

roundtable was convened by the CRCAH and co-hosted by the Kullunga Research

Network and NCSA in December 2008. The roundtable brought together 25 Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people with experience in lateral violence training

to develop a consensus for a lateral violence strategy.

A two day lateral violence course was piloted in Adelaide in 2009. I was a

facilitator of the program along with Yvonne Clark and Valerie Cooms. The

training was completed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers in the

Department of Families, South Australia. This course has been the basis for many

of the lateral violence workshops that have followed.

(ii) Victorian lateral violence community education

project

The Koori Justice Unit in the Department of Justice, Victoria (Vic DOJ),

hosted a lateral violence workshop in April 2009 which was attended by 80 Koori

community and government representatives. As a result of this workshop the Koori

Justice Unit is now funding the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health

Organisation (VACCHO) to raise the profile of lateral violence through community

education strategies.

In June 2009, the Vic DOJ funded VACCHO to produce a DVD on lateral violence.

A Canadian DVD used in previous workshops was an excellent way to introduce

lateral violence but it was felt that a similar production needed to capture the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context and experience.

VACCHO asked Richard Frankland, one of the Australian experts in lateral

violence, to produce the DVD. The Silent Wars – Understanding Lateral

Violence DVD was completed in August 2010. The 30 minute DVD uses

culturally-relevant hypothetical examples and features insight from respected

Koori community members. It explores the meaning of lateral violence, its

origins and impacts, and identifies strategies to reduce lateral violence. The

‘not-for-profit’ DVD has been distributed to VACCHO’s member

Aboriginal Health Organisations and other relevant stakeholders and will become

a much used resource in raising awareness about lateral violence.

The Vic DOJ has partnered with the Commonwealth Department of Families

Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) to provide further

funding to VACCHO, to utilise the DVD in a Lateral Violence Community Education

Project. I will discuss this project in greater detail later in the Chapter,

however, I do want to note the importance of this community education role being

placed in community controlled organisations like VACCHO. As I say again and

again, the conversations about and solutions to lateral violence must start in

our communities, not government, although government certainly has a role to

support these initiatives. Using Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff

from our own organisations will increase the cultural safety that is so

important in naming lateral violence.

(iii) Narrative therapy lateral violence

workshops

Naming lateral violence in our communities means sharing our stories about

lateral violence. The practice of narrative therapy takes this one step further,

using a culturally secure model of counselling and community work that empowers

participants to deal with lateral violence.

Narrative therapy draws on a strengths-based framework. Narrative therapy is

a respectful and empowering way of working with individuals, families and

communities and sees ‘people as the experts in their own lives and views

problems as separate from

people’.[17]

Viewing the problem as external from individuals is a very important shift in

counselling and community work because many other therapeutic models have been

based on western medical models that pathologise individuals, rather than look

at their strengths and resilience. When we consider the amount of negative

stereotypes that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders face, this is a very

important step in helping to break the hold of negativity and give people the

confidence and tools to tackle problems like lateral violence.

Another implication of seeing the problem as separate from the person is that

it opens up new ways of talking about issues. Narrative therapy calls this

‘externalisation of the problem’, allowing participants to see the

impacts that problems have on their lives and possible solutions.

Barbara Wingard, a respected Aboriginal Health Worker and expert in narrative

therapy, has led work in South Australia around narrative therapy with

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Barbara believes that narrative

therapy offers:

[A] way for Aboriginal counsellors to develop practices that are culturally

sensitive and appropriate. Many Aboriginal people have had put on them negative

stories about who they are. With narrative [therapy], we can go through their

journeys with them while they tell their stories, and acknowledged their

strengths in a re-empowering

way.[18]

Narrative therapy is also very interested in the historical, political,

economic and cultural factors that shape the stories in our lives. Again, this

helps to create context around problems like lateral violence.

Barbara Wingard, alongside colleagues Cheryl White and David Denborough from

Dulwich Centre, have been facilitating workshops where lateral violence has been

discussed. These workshops have taken place in Adelaide, Port Macquarie and

Cairns and have been attended by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and

non-Indigenous health workers working in Indigenous health, mental health, drug

and alcohol and youth services. These workshops have been based on a script for

an externalising exercise created by Barbara

Wingard.[19] The exercise is an

‘interview’ with lateral violence, with a person playing the

personification of lateral violence. While this sounds a little bit different

from the way we normally conduct workshops and training, Barbara Wingard has

seen how using this process of externalisation really assists people to speak

about confronting difficult problems and can also be a source of humour. Text

Box 4.3 provides an excerpt of the interview script.

| Text Box 4.3: A conversation with lateral violence |

|

|

Following the interview, participants are invited to share their own stories

of lateral violence. This workshop format shows that there are many different

ways for us to start talking about lateral violence. The important thing is that

they all take place in a space of cultural safety for participants.

(b) Confronting

bullying

Chapter 2 highlighted the pervasive impact of bullying in many areas of life.

Here I will focus on promising interventions in cyber bullying and the school

context.

Like all approaches to dealing with lateral violence, the first step is

naming the bullying and lateral violence in order to make it stop. However, we

also learn from these case studies that it is necessary to forge strong

partnerships with community and other organisations involved. In the case of the

cyber bullying project in Yuendumu we have seen collaboration between the

community groups, Police and the Department of Justice. In responding to

bullying of young people in schools we have seen a strong alliance between

schools, parents and children as part of the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project.

(i) Tackling cyber bullying in Yuendumu

The remote community of Yuendumu, which lies 293km north-west of Alice

Springs on the edge of the Tanami Desert, has faced tough times in recent

history. One of the largest remote communities in central Australia, the

majority of residents living in Yuendumu are from the Warlpiri clan. Yuendumu is

well known for its thriving artistic community and popular football team, the

Yuendumu Magpies.

However, late last year Yuendumu drew media attention for different reasons

when tensions within the Warlpiri people turned to violence after a 21-year-old

man was killed in a fight in a town camp in Alice Springs. This tragic death

brought the community to crisis, as members of the west camp sought traditional

payback for the death, and the south camp fled to Adelaide to escape the

violence that had erupted.

In the midst of this crisis mobile phones were used by young women to

perpetrate lateral violence through Telstra BigPond’s Diva Chat,

with emotionally charged messages flying between the camps. The anonymous

messages were a way of achieving ‘cyber payback’ by attacking and

provoking family rivals. This cyber payback spilled over into physical violence,

with men acting on the fights that happened online. At its worst, messages with

altered images of the deceased were sent through Diva Chat, an action

which violated Warlpiri cultural customs and appalled the community.

Determined to take action, community members turned to the local police for

help. But with no identifying information, the police struggled to hold

perpetrators accountable. Sergeant Tanya Mace from Yuendumu police station

describes that ‘my hands were tied. In the eyes of the people, the police

didn’t care’.[21] Desperate to stop the harassment, both camps even suggested shutting down the

mobile network entirely, and were willing to sacrifice the use of their mobile

phones.

Fortunately, with the help of Intelligence Officers in Katherine, Sergeant

Mace was able to get in contact with Air-G, the Canadian company who operate Diva Chat and convince them to take action. This contact was able to

identify the phone number associated with a user profile and once notified,

could shut that profile down within 24 hours.

Equipped with this new power, the police and community were able to develop a

reporting system that would help stop the lateral violence which continued to

fracture the community. Meetings were held with the two camps which allowed them

to establish their own laws for how the reporting system would work, and

nominate ‘Aunties and Elders’ so that young people could have

someone to go to and report offensive texts. The chosen representatives then

began to meet regularly with the police to report the usernames, so that

Sergeant Mace could contact Air-G in Canada and shut down the offending user

profiles.

Although the culture of shared phone usage still made it difficult to

identify specific individuals, the new system was successful in noticeably

reducing the bullying messages. The community felt safer and more confident that

the situation could be controlled. As Sergeant Mace explained, ‘The women

were happy because finally something was being

done’.[22]

When the exiled south clan returned to Yuendumu again in April, lateral

violence reared its ugly head again, and threats of riots were being made

through Diva Chat. Determined not to let the situation get out of hand,

Eileen Deemal-Hall from the Northern Territory Department of Justice, Sergeant

Mace and other community leaders held a meeting at the local police station with

young women from both camps. This meeting allowed young women to share their

experiences of lateral violence and explain how it affected them, and it allowed

Elders to deliver clear messages about culturally appropriate behaviour. This

behaviour was modelled through role plays, and young women were shown how to

stop perpetuating the cycle of lateral violence by ignoring provocative

messages.

Information about local programs and ways to get involved in the community

were also provided so that the young women could focus their energies elsewhere.

Nicki Davies, Co-ordinator of Mediation Services in Yuendumu, believes that this

kind of diversion is the key to stop bored and isolated residents from causing

trouble.

Whilst divisions still persist for some of the Warlpiri clan, most of the

community are keen to get on with things. Getting men re-engaged in the sport

which unites the community is one priority, ‘12 months ago all these

families were playing football together’ Nicki Davies

says.[23] Nicki Davies also has

plans to start a music group for Yuendumu’s residents to be able to

express their emotions about violence through songs.

Now the community turns to long term solutions to avoid the temptation of

lateral violence. Central Land Council’s ‘women’s

business’ meetings, and the recent government consultations on the

Northern Territory Emergency Response have given women the opportunity to come

together again and plan for Yuendumu’s future. Collaboration between the

Northern Territory Department of Justice, police and community groups through

the reporting system, meetings and workshops have built trust and confidence

between the groups. They continue to work together co-operatively to ensure that

young people experiencing and partaking in lateral violence can receive

education and assistance in a culturally safe and secure environment.

Although it has faced big challenges in the past year, the talented and

proactive families of Yuendumu are making progress, and the community continues

to build on its strengths and promote the proud Warlpiri culture it is best

known for. This is an excellent example, according to Eileen Deemal-Hall of

‘what a community in crisis can

achieve’.[24]

(ii) Solid Kids, Solid

Schools

Yamatji communities, families and

schools have been developing innovative ways to prevent bullying amongst young

people. Led by Associate Professor Juli Coffin from the Combined Universities

Centre for Rural Health (CUCRH), the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project

has built up strong evidence about the experience of bullying amongst Aboriginal

children, as well as developing new tools to prevent bullying.

Yamatji country is in the mid-west region of Western Australia and takes in

the area from Carnarvon in the north, to Meekatharra in the east and Jurien in

the South. This region covers almost one fifth of Western Australia. Of the

nearly 10 000 students in the mid-west education District, nearly 20% of the

students are Yamatji children and young

people.[25]

The Solid Kids, Solid Schools project began in 2006. The

project came out of the fact that while there is information on bullying of

non-Aboriginal children, virtually nothing was known about the experience of

bullying for Aboriginal children.

Solid Kids, Solid Schools is a joint project between the CUCRH, and

Child Health Promotion Research Centre at Edith Cowan University. The project

was funded by Healthway, an independent statutory body to the Western Australian

Government that provides funding grants for health promotion activities. A

further two years funding was also sourced from the Australian Research Council

to help develop resources after the more formative work and research had been

completed.

The Solid Kids, Solid Schools project became much more than just

research. In consultation with the Yamatji communities, the Solid Kids, Solid

Schools project had a strong brief to develop tools for addressing bullying,

including a website, comic books and a DVD/teaching package based on the

research undertaken.

Critical in developing this approach was the Aboriginal Steering Group made

up of community leaders. The Aboriginal Steering Group was involved in each

phase of the project and provided a link between the researchers and community

which increased community ownership over the project. The Solid Kids, Solid

Schools project is an example of best practice in conducting research with

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities.[26] This also included

the employment of several male and female Aboriginal research assistants to help

make the interviews as culturally secure as possible.

During 2006 and 2007 around 260 people were involved in the Solid Kids,

Solid Schools project through semi-structured interviews. Of these, 119 were

primary school students, 21 were high school students, 40 were parents and

caregivers, 18 were Elders and 60 were either Aboriginal teachers or Aboriginal

and Islander Education Officers

(AIEOs).[27] The participants came

from a variety of schools in the regional towns, rural and remote areas in the

mid-west. In the most part, the remote schools had up to 99% Aboriginal

enrolment while the regional towns and rural areas had lower levels of

Aboriginal enrolment.[28] The

research also included Karalundi Aboriginal Education Centre, an independent

boarding school for Aboriginal children from Kindergarten to Year 10, about 60km

from Meekatharra.

Some of the results of the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project are

discussed in Chapter 2 of this Report. The research showed without a doubt that

bullying, and primarily intra-racial bullying, was a pervasive problem for

Yamatji children, with serious consequences for their education and community

life. I applaud the researchers in developing robust evidence, as well as such

sensitive ways of hearing the experiences of children, families and AIEOs.

The research phase of the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project was just

the starting point. In 2008 the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project ran

community focus groups to plan for sustainable school and community based

bullying prevention programs. By 2009, the Solid Kids, Solid Schools project was able to incorporate all the feedback from the past three years to

roll out the programs. The quality of community engagement and the creation of a

culturally secure environment have meant that the voices of Yamatji children,

young people, parents and AIEOs are reflected in the programs created through

this process.

Solid Kids, Solid Schools website

The Solid Kids, Solid Schools website (www.solidkids.net.au) is a dynamic source

of information about bullying, with pages tailored directly for children and

young people (‘Solid Kids’), parents and care givers (‘Solid

Families’) and schools (‘Solid Schools’). It incorporates

artwork by Aboriginal artists, Jilalga Murry-Ranui and Allison Bellottie and

promotes Yamatji culture.

The ‘Solid Kids’ web page has easy to read, age appropriate

information including practical ways children and young people can get help with

bullying. It also includes a game and a series of comics designed by a young

Aboriginal woman, Fallon Gregory, which deal with issues around bullying.

As well as the comics, the website also provides a place for creative

expressions on bullying. Text Box 4.4 is a poem, ‘Diva Chat’ by Nola

Gregory, a well respected Aboriginal youth worker who offers education and

support to children and young people in the Geraldton area.

| Text Box 4.4: Diva Chat by Nola Gregory |

|

|

‘Solid Families’, provides practical advice about talking to

children (4-12 years) and young people (13-20 years) about bullying, as well as

ways of working with schools to address bullying. The information includes

quotes from parents involved in the research and is empowering to parents.

‘Solid Schools’ includes information drawn from ‘Sharing

Days’ held in Geraldton, Meekatharra, Shark Bay and Carnarvon in 2008,

attended by AIEOs and Aboriginal teachers to discuss ways to support Yamatji

children involved in bullying.[30] These ‘Sharing Days’ brought together great experience and wisdom

about bullying and Aboriginal education more broadly and form the basis of the Solid Kids, Solid Schools approach to developing partnerships with

Aboriginal families, schools and students.

As well as easy to read summary information and tips, the ‘Solid

Schools’ section includes a comprehensive review of bullying and related

issues. The review gets schools, including AIEOs and Aboriginal parents to

critically and holistically look at whether or not the school is providing an

environment where bullying is being addressed appropriately. The 10 areas of

focus are:

-

solid school planning

-

solid school ethos

-

solid family links

-

solid understandings of cultural security

-

solid understandings about bullying

-

solid guidelines and agreements

-

solid management of bullying situations

-

solid classroom practice

-

solid peer support

- solid school environment.

The review tools are not just specific

to Yamatji children and could be used in any school community that includes

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, particularly where there is

evidence of bullying.

Educational DVD

A DVD, We all Solid, also helps to communicate the messages about

bullying to Aboriginal children and young people. Again, the DVD is by and for

the Yamatji children, youth and the wider community and reflects some of the

main stories that were raised during the research. It is envisaged that the DVD

will be widely distributed, making it a complementary education tool to the

website.

Teaching package

A comprehensive teaching package aimed at middle to upper primary and high

school ages up to year ten has also been developed to complement the DVD

resource. It contains a mix of structured and semi-structured activities and

workshop ideas for teachers, counsellors and youth workers for example in

dealing with these issues.

Social marketing

The project has recently secured three years of funding from Healthway to

develop social marketing tools for use with the wider community on the issues of

bullying. This next phase involves developing some infomercials, print media and

radio messages around the issues and implications of bullying.

The Solid Kids, Solid Schools project has been recognised for the

contribution it has already made, winning the Outstanding Achievement Award for

the Injury Control Council’s Annual Community Safety Award in 2010. The

project shows us what is possible when we hear what communities think about

tough issues like bullying. Juli Coffin describes the impact of the project:

Although our research is still a work in progress, we are beginning to see

more clearly the picture of life faced by our [Yamaji] children within schooling

and community settings... This information is just the beginning and it was only

possible with the strength and support of the Yamaji community, [who are]

already leaders in making things better for their

kids.[31]

(c) Dispute

resolution

In Chapter 2, I discussed how the process of colonisation undermined our

traditional ways of resolving conflicts based on our complex customary laws.

When thinking about lateral violence, it is important to never lose sight of the

fact that our people managed to coexist for over 70 000 years before the

Europeans arrived. This fact makes me confident that we can once again enjoy a

life where conflict is properly managed and lateral violence does not rule our

communities.

However, we can’t just wind back the clock to the time before

colonisation. Not all of our traditional dispute resolution processes will fit

in today’s world. We live in a world bound by the western legal system.

This impacts on how we can resolve our conflicts. As the National Dispute

Resolution Advisory Council (NDRAC) notes:

In contemporary society, Indigenous people live in two overlapping worlds,

the western and traditional, and neither is fully capable of dealing with

disputes involving Indigenous people. Purely western models of dispute

resolution are often incongruent with the culture of Indigenous people and fail

to meet many of their needs. At the same time, European colonisation has

weakened many traditional ways of resolving disputes between Indigenous

people.[32]

Similarly, we also now face problems like alcohol abuse and indeed, lateral

violence that did not exist before colonisation. Again the NDRAC notes that:

[T]raditional structures may not be well equipped to deal with western

problems, such as alcohol abuse. Weakened traditional processes are being

confronted by new problems outside past

experience.[33]

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) has been identified as a potential for

dealing with community conflicts. Text Box 4.5 provides a definition of ADR.

| Text Box 4.5: What is Alternative Dispute Resolution? |

|

|

However, it is important to note that disputes or conflicts are never finally

resolved, even with the best ADR processes in the world. In successful

processes, conflict is transformed to something that both parties can live with,

but it never truly goes away because individuals and communities have to live

with the impact of the original conflict. Nonetheless, it is still important to

put in place healthier ways of dealing with conflict through dialogue to prevent

further impacts into the future.

ADR has been an area of research and program development with Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people since the 1990s. In particular, the Solid Work

You Mob Are Doing report by the Federal Court studies a selection of

promising ADR methods, including mediations in urban, rural and remote

communities in a range of contexts including Community Justice Centres,

Community Justice Groups and community controlled

organisations.[35] They found that

successful programs managed to bridge the divide between Western law and our

cultural ways.

Dispute resolution has also been a focus of research in the native title

system. More information about the dispute resolution developments and their

connection to lateral violence can be found in the Native Title Report

2011.

The case studies that I will highlight here, the Mornington Island

Restorative Justice Project and the Victorian Community Mediators, chart new

ways forward in this complex intersection between Western law and customary law.

While these projects come from very different places, they both create

culturally safe places for conflict to be resolved. This is the ‘pointy

end’ of lateral violence intervention. If we can start to resolve some of

the feuds that have spanned generations, we can break the cycle of lateral

violence. Importantly, these sorts of projects also prevent lateral violence

through the creation of cultural safety and the reestablishment of our positive

cultural norms.

(i) Mornington Island Restorative Justice

Project

The Mornington Island Restorative Justice (MIRJ) Project is one of only a

handful of ADR projects working specifically with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders. The project tells the story of a remote community taking back control

of how they handle conflict and progressively creating culturally safe places to

address the consequences of lateral violence.

Mornington Island

Mornington Island is the largest Island in the Wellesley Island group,

located in the lower Gulf of Carpentaria. The surrounding waters supports the

ongoing hunting tradition and is an important component of family life and

household economy. It is an extremely remote community, approximately 125km

north-west of Burketown, 200km west of Karumba and 444km north of Mt Isa.

Mornington Island is home to around 1 100 people.

The traditional owners of

Mornington Island are the Lardil people. The Lardil people had limited contact

with the outside world until the 1900s when a Uniting Church Mission was

established on Mornington Island. As we have seen in the case study on Palm

Island in Chapter 2, the creation of missions under the Aboriginal Protection

and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld) saw other Aboriginal

groups forcibly removed from their land and relocated to these mission and

reserves. Consequently, Mornington Island is now also home to the Yangkaal,

Kaiadilt and Gangalidda people.

Establishing cultural safety in the MIRJ

The MIRJ project was established in 2008. Initially funded by the

Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department under the Indigenous Justice

Program, it is managed by the Dispute Resolution Branch in the Queensland

Department of Justice and Attorney General. Since July 2009 the Commonwealth and

Queensland governments have funded the project jointly. It is still a pilot

project and is yet to secure long term funding.

The MIRJ project is a mediation or peacemaking service that recognises and

respects kinship and culture while still meeting the requirements of the

criminal justice system. The objectives of the project are to:

-

enhance the capacity of the community to deal with and manage its own

disputes without violence by providing training, support, supervision and

remuneration for mediators -

reduce Indigenous peoples’ contact with the formal criminal justice

system -

encourage community ownership of the program

-

improve the justice system’s responsiveness to the needs of the

community - increase the satisfaction with the justice system for victims, offenders,

their families and the broader

community.[36]

The

development of the process is an important beginning in the story of the MIRJ

project. The project only became operational in September 2009, following

lengthy consultation and negotiation processes between 2008-2009. Around 200

community members, representing all the major groups on the Mornington Island,

actively participated, as well as the other government and criminal justice

stakeholders. The Project Manager, Phil Venables, sees the fact that an

appropriate amount of time was allowed as crucial in building the trust and

partnership with the community.[37]

As result of consultations, 28 Elders signed a document agreeing to the

practice and procedures for the MIRJ project. Text Box 4.6 is from the document

signed by Elders and explains what peacemaking is and what sorts of conflicts go

to peacemaking.

| Text Box 4.6: Peacemaking |

|

|

Establishing the rules was seen by the Elders as a way of connecting back

with traditional ways of doing things. Ashley Gavenor, a prominent community

member stated:

You need rules [for peacemaking] just like the rules for sharing a turtle.

Everyone knows what they are. The way back to those rules for peacemaking is by

doing it every day. Then talk about it and get better at it. You just do it and

do it and people will get used to

it.[39]

It is also an attempt to reconcile western and tradition laws with one Elder

describing the process:

We will get our rules (for peacemaking) and show you what they are and you

tell us your rules...then we can mix them up and make them strong

together.[40]

Cultural safety has been the consistent theme during the MIRJ project,

starting with the formative involvement of Elders and then the recruitment of

four male and four female Elders as Mediation Support Officers. They are paid at

the same level as all mediators in the Department of Justice. They are not

required to have formal accreditation as mediators, recognising that their skill

in mediation comes from their cultural background and ability to provide a

culturally safe process for participants.

The MIRJ project draws significantly on cultural and kinship traditions.

Nearly all mediations involve extended family. Project staff aim to give

participants control over who are the appropriate people to attend. For example,

the uncle known as Gagu (mother’s eldest brother in Lardil language) has a

traditional disciplinarian role. Their attendance at the mediation signals the

importance of the meeting.

Mediations do not just take place in the MIRJ office. A community member,

Delma Loogatha describes some of the different locations:

Some [mediations] are real traditional, where you go to the festival grounds

traditional site for square up] or for safety, out front of the police station.

Sometimes it is better for a quiet mediation at

home.[41]

Successes of the MIRJ Project

The MIRJ project has now successfully dealt with 63 major conflicts. Of

these, 28 related to family conflict, 20 were court referred victim-offender

mediations and 15 dealt with conflict in other ways (not necessarily through a

formal mediation).

Critical to the community support for the MIRJ project were early successes

in resolving large and significant inter-family disputes. These mediation

meetings involved 70 participants in one mediation meeting and 100 in another.

This sort of crisis intervention helped to defuse the tension before it got

further out of hand. Similarly, the fact that more than half of the referrals

are being made by community members tells the story of the community acceptance

and cultural safety created by the project.

Another measure of the confidence in MIRJ project is the willingness of

courts to refer matters, including more serious assaults. In three recent cases

where the prosecution had submitted for a custodial sentence, the Magistrate

ordered a non-custodial sentence citing the defendant’s successful

participation in mediation as a reason for the decision. Similarly, of the 16

successfully fulfilled court ordered mediations, eight had their charges

withdrawn by the prosecutor and eight received a reduced penalty because of

their successful participation in

mediation.[42]

Although the number of court ordered mediations is currently comparatively

low, it is still an important step in creating diversion opportunities from the

criminal justice system. Furthermore, it also makes offenders accountable to

their victims and community and is focused on resolution of the issues, not just

locking people up. The Elders have also expressed their appreciation that they

have been able to have input in prosecution decisions to withdraw charges

following successful completion of mediated agreements. This is seen as tangible

support for the Elders efforts to strengthen their leadership in the

community.

The MIRJ project is still only a pilot program and is yet to secure long term

funding. Given the successes and amount of time and goodwill that both the

community and Department of Justice and the Commonwealth

Attorney-General’s Department have invested so far, it is crucial that

this project continues as a way of addressing lateral violence.

The project

is working in partnership with the community based Junkuri Laka Justice

Association over the coming year to take over the coordination of mediation and

provide more community ownership and sustainability. Work is continuing in

relation to ongoing funding.

The MIRJ project shows us what communities, with assistance from government,

can do to resolve conflicts. It also speaks to the inherent strengths of our

people. Phil Venables, the project manager, reflects, ‘much is made of

grudges and payback but not much is made or people’s capacity for

forgiveness’.[43] We should

never lose sight of the strength of forgiveness in addressing lateral

violence.

(ii) Koori Mediation Model: The Loddon-Mallee

pilot

Since the 1990s ADR programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities have been developed in a number of

locations.[44] Although the Koori

Mediation Model is not operational until October 2011, it is the first program

of its kind to specifically address lateral violence.

Development of the Koori Mediation Model

The Koori Justice Unit, within the Vic DOJ’s Community Operations and

Strategy Branch, is primarily responsible for coordinating the development and

delivery of Victoria’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander justice

policies and programs across the Victorian Government and justice system,

primarily the Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement. In April 2009, the

Koori Justice Unit hosted a two-day seminar on lateral violence, as discussed

earlier in this Chapter.

One of the specific outcomes of the April 2009 seminar, was the development

of a Koori Mediation Model by the Courts and Tribunals, in conjunction with the

Koori Justice Unit and Koori Caucus members. This was subsequently endorsed at

the Aboriginal Justice Forum in May 2009. Koori mediation was identified as an

important gap in existing services and a potentially effective response to

lateral violence when it occurs in the community.

The next step was a workshop that was held on 13 August 2009. Jointly hosted

by the Koori Justice Unit and the Alternative Dispute Resolution Directorate

(ADRD), it provided an opportunity for members of the Koori Caucus to begin

discussion on a Koori Mediation Model. The objectives of the meeting were to

conceptualise what a Koori model of mediation might be, and to set a future

direction.

On the strength of that work a pilot program was developed and funded for the

Loddon-Mallee region.

The Loddon-Mallee pilot

The Loddon-Mallee area, in the north-west corner of Victoria, takes in the

major rural centres of Mildura, Robinvale, Swan Hill, Echuca and Bendigo. The

area has the second highest regional population of Aboriginal people in

Victoria, making up 15% of Victoria’s total Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander population. The traditional owners of the Loddon-Mallee area are the

Wamba-Wamba people.

The Loddon-Mallee area was chosen for the pilot due to the reported problems

caused by lateral violence and receptiveness of local community organisations to

the concept.

The pilot Koori Mediation Model in Loddon-Mallee is being driven by ADRD. It

funds two full time Dispute Assessment Officer positions, based in Bendigo and

Mildura (Identified Positions) and a Regional Manager.

It is envisaged that the holder of these positions will coordinate five local

Lateral Violence community workshops/forums to raise awareness on lateral

violence and to help identify local community members who may be interested in

being trained in Koori mediation and conflict resolution. The workshops will be

facilitated by Richard Frankland, who has had a leading role in running prior

workshops, developing relevant resource materials and undertaking research in

the area of lateral violence. The workshops will be run in the five main centres

of the Loddon-Mallee region: Mildura, Robinvale, Swan Hill, Echuca and Bendigo.

When interested community people have been identified as potential Koori

mediators, training will be provided in two models of response to lateral

violence: (i) conflict resolution, and (ii) mediation. The conflict resolution

approach is less formal and may enable situations to be defused without being

taken further. The mediation approach is more structured, and is suitable for

those needing a more formal process, or for situations where conflict resolution

has not been sufficient.

Once trained, these people will function as a ‘pool’ of Koori

mediators for the Loddon-Mallee region. The Dispute Assessment Officers will

coordinate and support the mediators, and match them with the referrals that are

received. A particular strength of this model is that due to the geographic

spread of communities from which the mediator pool will be drawn, there should

always be an independent mediator available, ie one who is not connected by kin,

proximity or circumstance to the lateral violence incidents that will be

referred to the service. It is also envisaged that the Dispute Assessment

Officers will coordinate opportunities for peer support between the

mediators.

An expanded Koori Mediation Model: The vision for

Victoria

If funds can be secured for a state-wide roll-out of the Koori Mediation

Program, the ideal structure has been identified as follows:

-

Several Dispute Assessment Officers in each region, at least one being a dedicated position to support the Koori Mediation Model.

-

Capacity to provide regular lateral violence workshops in all

locations, (rather than localised “one-offs” to get the program

started). This would create a permanent community awareness-raising mechanism

and enable new Koori mediators to be continuously identified to replace those

who move on. - Capacity to provide ongoing training and wraparound support to all

mediators. This remains one of the most vital determinants of the quality of

the program, because the value of the Koori Mediation Model to the community

will depend upon the skill and sensitivity of the mediators

themselves.

Now that the Dispute Assessment Officer positions have

been filled, it is hoped that the Loddon-Mallee Koori Mediation Program pilot

will commence in October 2011, and demonstrate how a community-driven response

to lateral violence can improve the wellbeing and safety of Koori communities in

Victoria.

(d) Healing and social

and emotional wellbeing

Chapter 2 has discussed some of the ways the social and emotional wellbeing

impacts of lateral violence are felt. At its most tragic extreme is the high

level of suicide and suicide attempts in our communities, compared to the

non-Indigenous population. The case study below, of the Family Empowerment

Project in Yarrabah, was developed as a direct response to this increased risk.

Lateral violence requires healing approaches. The Social Justice Report

2008 provides a detailed selection of case studies of community initiatives

creating culturally safe healing

spaces.[45] Many of these sorts of

programs can help in healing the harm caused by lateral violence. Healing

approaches also challenge negative stereotypes, making our culture strong and

safe enough to prevent lateral violence.

The Family Empowerment Program in Yarrabah is a great example of a community

generated program that focuses on the healing needs of participants. Although it

was not set up to explicitly address lateral violence, by building conflict

resolution skills, dealing with trauma, grief and loss and promoting strong

culture, it attacks lateral violence on a number of fronts.

(i) The Family Wellbeing Program

The Family Wellbeing Program is a community led initiative implemented in

Yarrabah responding to a spate of suicides and suicide attempts in the

mid-1990s.[46] It empowers

individuals and families to try and prevent suicide and increase social and

emotional wellbeing. This can also help address lateral violence.

Yarrabah is a coastal community located approximately 50km south of Cairns.

The Gunggandji and Yidinji people are the traditional owners of the lands around

Yarrabah.[47] Yarrabah has a

population of approximately 3 000 residents.

In 1892 a mission was established in Yarrabah leading to the forcible removal

of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from surrounding

areas.[48] This has had long lasting

consequences for the community of Yarrabah. For instance, the lack of adequate

housing in Yarrabah has meant that that ‘enemies often found that they had

each other as

neighbours’.[49]

Forcible removal of children from their families has also had a big impact on

the community of Yarrabah with up to 80% of the population either members of

Stolen Generations or descended from Stolen Generations

members.[50]

Yarrabah has struggled with many of the same issues facing our communities,

including family violence, alcohol abuse and unemployment but they have also

courageously decided to tackle suicide and family wellbeing, despite the

difficult circumstances.

Description of the Family Wellbeing Program

The Family Wellbeing program was first established in Adelaide by Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander leaders who wanted to help our people deal with the

transgenerational grief, loss and despair being experienced a result of

colonisation.[51] Due to its success

the program was adapted into other communities including Yarrabah.

The Family Wellbeing Program in Yarrabah grew out of consultation with

Yarrabah community leaders who wanted to establish a program where they could

pass on life skills and values in ‘overcoming adversity and maintaining a

strong sense of family in the face of hostile dominant

culture’[52] as a means of

suicide prevention. The Family Wellbeing Program in Yarrabah is run by the

Gurriny Yealamucka Health

Services.[53]

The program uses empowerment, capacity building, and conflict resolution to

achieve better social and emotional wellbeing. [54] The Family Wellbeing Program

focuses on:

-

empowering participants

-

life and relationship skills

-

communication

-

conflict resolution skills

-

problem solving skills

-

understanding and gaining control over conditions affecting participants

lives - social and emotional

wellbeing.[55]

The

Family Wellbeing Program in Yarrabah also has a strong focus on leadership

skills that can be applied in community and family

contexts.[56]

It employs activities such as walking groups, healing art camps, men’s

groups and recently a one-day men’s forum on justice issues, as part of

its holistic approach to addressing the emotional and social wellbeing of its

participants as well as lateral

violence.[57]

The Family Wellbeing program also looks at grief, loss and trauma and ways of

dealing with these issues.[58] The

development of anger management skills, coping strategies, problem solving and

conflict resolution skills, provides opportunities for individuals to become

increasingly connected and minimise the divisions that colonisation has created

within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities.[59]

The program provides participants with a culturally safe environment to

discuss their experiences and reflect on their feelings, emotions and

relationships. Darren Miller, co-ordinator of the Family Wellbeing Program in

Yarrabah, states that participants have drawn on their own life experiences in

sharing possible solutions in dealing with some of the issues around lateral

violence. This process of healing, self-reflection and understanding is a

powerful tool in combating lateral violence as it empowers participants to deal

with life’s challenges, manage family

conflict[60] and identify the

strength and resourcefulness they have as individuals and as a

community.[61]

Men in the Yarrabah community have used the skills they have gained in the

Program to lead and facilitate community events such as NAIDOC Week. They have

assumed responsibility and become role models to Yarrabah’s young people,

passing on their knowledge, values, culture and traditions. As a result, young

people in Yarrabah have become increasingly engaged in traditional and cultural

activities such as camps, hunting and fishing. Young people in Yarrabah have

also utilised the skills they have learnt in areas such as art and assisting in

the design of programs.[62] These

sorts of activities create cultural safety and cultural revitalisation in

communities. The Family Wellbeing Program is showing that strong culture is a

powerful way of preventing lateral violence.

Success of the Family Wellbeing Program

A number of studies have favourably evaluated the effectiveness of Family

Wellbeing Program in increasing capacity and empowerment, improving social and

emotional wellbeing and reducing violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander communities. The reported success of the Family Wellbeing Program in

addressing these issues has made it one of the most sought-after and recognised

Indigenous empowerment and skill development

programs.[63]

David Baird, Chief Executive Officer, Gurriny Yealamucka Health Services

Aboriginal Corporation, states that there is anecdotal evidence that the Family

Wellbeing Program is helping participants change their lives. He reports

participants giving up drinking, and smoking, staying out of jail and the

criminal justice system and a reduction in family violence as evidence of the

positive impact the Family Wellbeing Program is having on those that take part

in it.[64]

Research studies have shown that participants in the program have reported an

improvement in family relationships, increased connectedness with children and

community, healthier lifestyles and being more at

peace[65].

The resulting connectedness and empowerment has increased participants

respect for self and others, self-reflection and awareness, hope and vision for

a better future, self-care and healing, enhanced parenting, and capacity to deal

with substance abuse and

violence.[66]

Identity and spirituality were seen by many to be central in dealing with

contemporary issues, such as lateral violence, facing Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities.[67] One

participant stated:

Because all of our culture was taken away from us, there was no way of really

keeping a clear picture of our spirituality. There are all different beliefs as

well with the stolen generation (male participant, Yarrabah, 2005

data).[68]

The program has helped participants to identify their strengths and in

particular, the resourcefulness of the Stolen Generation in overcoming

hardships.[69] This has enabled

participants to take ‘the necessary steps towards reasserting their

identity’.[70]

The skills and healing gained from the Family Wellbeing Program has led some

participants to be more active in the

community.[71] Some participants

have gone on to form networks that have addressed issues around health, school

attendance, family violence, alcohol and drug misuse, and over representation of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in the criminal justice

system.[72] This is where we see the

ripple effects of healing and empowerment, with individuals taking

responsibility to be part of the solution to some of the issues facing the

community.

While the Family Wellbeing Program has made positive impacts in the lives of

participants, it can’t solve all the problems facing the community of

Yarrabah. Issues around funding and structural disadvantage such as

over-crowding and unemployment have to be addressed. Darren Miller adds that the

program would reach its full potential with the introduction of complementary

activities and programs.[73]

Nonetheless, the Family Wellbeing Program shows us how communities can

confront complex problems by drawing on holistic healing methods which blends

cultural renewal and spirituality with conflict resolution and other problem

solving skills. Most importantly, it empowers participants because it is

culturally safe, taking a zero tolerance approach to lateral violence.

4.4 Creating cultural

competency

Having looked at some approaches that are addressing lateral violence at the

community level, I will now look at the role of governments, NGOs and industry

who work in our communities. This is necessary because nothing occurs in a

vacuum. The way our communities operate will always be shaped and informed by

external influences. These influences can either empower and support our

communities or undermine them.

Given that this Report’s purpose is to start a conversation, again this

section is not exhaustive and requires further empirical research. However, the

case studies and analysis, promote good practices that are occurring and

identify key challenges to be addressed.

Governments, NGOs and industry cannot ‘fix’ lateral violence

through intervention; this will only exacerbate the issue. Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander relationships must be fixed ourselves, from within our

communities. However, this does not absolve these external stakeholders of

responsibilities to:

-

remove the road blocks that inhibit Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander

peoples from taking control -

refrain from actions and processes that divide us

-

create environments where our cultural difference is respected and

nurtured - remove the structural impediments to healthy relationships in our

communities.

To meet these responsibilities governments, NGOs and

industry must be sufficiently culturally competent to act in accordance with

Juli Coffin’s model of cultural security that I outlined earlier in the

Chapter. Under this model, cultural competency extends beyond individual

awareness to incorporate systems-level change. The definition outlined in Text

Box 4.7 encapsulates this breadth.

| Text Box 4.7: Cultural competence |

|

|

A broad conception of cultural competency akin with Juli Coffin’s model

of cultural security does not occur just in the parts of an organisation

responsible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy and service

delivery. Creating true cultural competency is an organisation-wide process. In

regard to government service delivery, this requires building the capacity of

all those involved in policy formation and implementation: from the Minister,

through to policy makers right down to the on-the-ground staff who implement the

policy.

(a) Moving towards

cultural competency

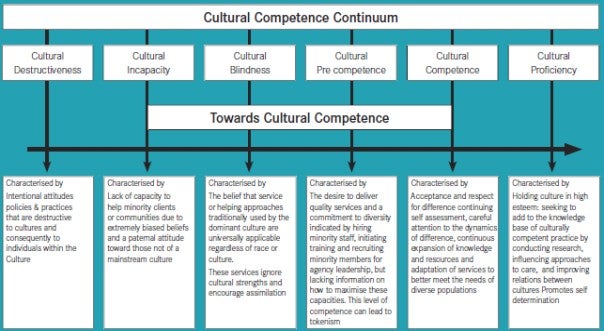

The health services sector has produced a burgeoning body of research on the

concept of cultural competency. Terry Cross’ research in the United States

has led to the development of a cultural continuum for mental health

practitioners to increase their competence in working with minority

populations.[75]

Tracey Westerman’s research focusing on service providers working with

Aboriginal youths at risk has validated this continuum in the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander context.[76] VACCA’s Aboriginal Cultural Competency Framework which guides

mainstream child and family services towards cultural competency also

incorporates a continuum which is outlined below in Figure

4.1.[77]

| Figure 4.1 – Cultural competence continuum[78] |

|

Similarly, Juli Coffin’s model of cultural security also recognises

that cultural competency is on a continuum. She argues that awareness and safety

mechanisms need to be supported by brokerage and protocols to progress to

cultural security.

Brokerage involves two-way communication where both parties are fully

informed about the subject matter in discussion – this is consistent with

the principle of free, prior and informed consent. Brokerage is about creating

community networks between service providers and community members. Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander staff employed by the service provider can play a

crucial role as brokers to develop these networks. Text Box 4.8 provides an

example from the Solid Kids, Solid Schools program of how AIEOs can

broker networks.

| Text Box 4.8: Aboriginal and Islander Education Officers as brokers |

|

AIEOs can be utilised as ‘brokers’ by:

|

Networks and relationship building must be supported by protocols. Protocols

are the strategies to formalise the fact that service delivery must be developed

in consultation with the particular

community.[80] Protocols include

agreement on culturally informed practices that set rules for engagement with a

particular community in relation to the delivery of services. Text Box 4.9

provides a practical example of a protocol.

| Text Box 4.9: Protocols shaping service delivery |

|

The example below, drawn from Juli’s Coffin’s work, is a After talking with the Aboriginal health worker, midwives discovered that |

In developing the cultural competency of an agency or organisation VACCA

argues it is essential to remember that cultural competency:

-

needs to be developed over time

-

requires a whole-of-agency approach and be driven by strong leadership

within the agency -

relies on respectful partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

organisations -

requires personal and organisational reflection

- is an ongoing journey and partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander

communities.[82]

The key

lesson that can be drawn from this body of literature is that creating cultural

security through cultural competency is not something that an agency or

organisation can simply purchase off a shelf. Cultural competency must be built

over time through a deliberate process that seeks to build the capacity of the

entire organisation, and this must be done in partnership with Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander communities.

Next I further explore how cultural competency can create engagements that

strengthen and empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

(b) Hearing Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander voices

In Chapter 2 I have already discussed how poor engagement processes can

contribute to conditions that lead to lateral violence. In this section I will

look at how governments, NGOs and industry can undertake their work with

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in a culturally secure manner

to prevent lateral violence. First and foremost, they must ensure that they hear

our voices. This is consistent with Juli Coffin’s concepts of brokerage

and protocols and requires effective engagement.

(i) The commitment to engage

There is a clear policy commitment across all governments in Australia to

engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Council of

Australian Governments’ (COAG) National Indigenous Reform Agreement is the benchmark agreement for Indigenous policy activity in Australia and

includes an Indigenous Engagement

Principle.[83] This principle is

outlined in Text Box 4.10.

| Text Box 4.10: Indigenous Engagement Principle |

|

Indigenous engagement principle: Engagement with Indigenous men,

|

In addition, the Australian

Government[85] has developed a

framework for engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, Engaging Today, Building

Tomorrow.[86] More than 2 000

copies of this framework were distributed across Australian Public Service

agencies since its release in National Reconciliation Week

2011.[87]

It is pleasing that the Australian Government has set their intention in this

way and I will continue to monitor the performance of this engagement framework.

However I am concerned about the implementation of these commitments. Words in a

policy document aren’t enough. Below I will look at how they can bring

these good intentions to life and hear our voices in ways that don’t

further divide us.

(ii) Building the capacity to engage

Effective engagement is one of the key areas where governments must develop

their competency if they are to work with us as enablers to address lateral

violence. This challenge of effective engagement is not a new one. The inability

of government to engage effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples has been subject to significant international

scrutiny.[88] Toni Bauman has noted

her continued concern with the way in which governments engage with Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples:

The incapacity of governments to engage with Indigenous communities and

arrive at meaningful, sustainable and owned outcomes through highly specialised

skilled facilitation and participatory community development processes has

troubled me for many years. The modus operandi of 'consultation' has mostly been

one-way communication in 'meetings' in which talking heads drone on, poorly

explaining complex information and concluding by asking: 'Everyone agree?'. The

response: hands raised half-heartedly and barely perceptible nods. Outside the

meeting, participants typically have little or no understanding of what they

have agreed to, the possible repercussions of agreement, or the short-, medium

and long-term resources available for implementation

requirements.[89]

This type of engagement is not culturally secure. Echoing Coffin’s

research, Bauman continues to suggest that merely being aware of

‘issues’ that impact on Indigenous communities does not necessarily

translate into ‘skills of engagement and

communication’.[90]

There is clearly a need for government to be ‘up-skilled’ in how

it engages with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. One way

forward, as suggested by the Indigenous Facilitation and Mediation Project in

the Native Title Research Unit at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Studies is the use of procedural experts who:

[C]ould assist government, other stakeholders and Indigenous communities in:

ensuring informed decision-making processes and greater co-ordination of a

whole-of-government approach including native title agreement-making;negotiating ways in which Indigenous people prefer to do business that match

their local needs and in which they can secure equal partnerships with

government representatives and other parties; and- ensuring that parties have what is required to enable them to negotiate

effectively.[91]

These

experts act as cultural brokers. In recognition of this need to increase

cultural competency, the Indigenous Facilitation and Mediation Project

recommended the development of a national network of highly trained process or

engagement practitioners.[92] This

is an idea that could be applied to other areas of policy and program

development, in addition to native title.

I agree with Bauman and the Indigenous Facilitation and Mediation Project,

effective engagement requires developing skills such as communication,

facilitation and negotiation that extends well beyond cultural awareness. In

other words governments need to develop culturally competent procedural experts

who can act as brokers to develop networks between an agency or organisation and

the community.

Engagement also needs to be everyone’s business. Cultural security

cannot be created if effective engagement is restricted to expert brokers. The

role of the broker is to assist in developing relationships, but all those who

work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities must be able to

provide cultural security. These experts should help develop the competency