Part 1: Our women and girls' voices

Download the Report

Cairns women

Chapter 1 Background to report and methodology

1.1 Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices) project background

In June 2017, the Indigenous Affairs Group of the Commonwealth Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, now the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) and the Australian Human Rights Commission partnered on a national conversation to investigate how to best promote the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls and their communities.

This project was named Wiyi Yani U Thangani which translates to ‘Women’s Voices’ in my language, Bunuba.

The key aim of the project has been to elevate the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls, and to reflect the holistic and interconnected nature of their lives. Crucially, the project would also provide recommendations to improve the lives of women and girls across a broad range of subject areas.

The Wiyi Yani U Thangani Project fills a major gap in the representation of the voices of our women since the Women’s Business engagements in 1986, which was the first and only time our voices have been heard as a collective.

The Women’s Business engagements were also the last national consultation conducted by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women.

The Women’s Business Report sought to understand what women considered to be their critical needs, and to provide guidance to the Commonwealth Government on suggested measures that might be taken to effectively address these needs.

Wiyi Yani U Thangani has built on the legacy of this work through a strengths-based national engagement process, seeking community reflections on the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls’ rights over the past 34 years, and into the present day.

Importantly, in the Wiyi Yani U Thangani process we also heard directly from our girls (12-17 years old) whose voices are so critical to any conversation about the future of our peoples.

The Wiyi Yani U Thangani process captures what communities consider to be their key strengths and concerns, what principles they think ought to be enshrined in the design of policies, programs and services, and what measures they recommend ought to be taken to effectively promote the enjoyment of their human rights into the future.

1.2 Acknowledgements

There are many people whose individual and collective efforts have made the Wiyi Yani U Thangani project possible. Members of my team past and present have given their hearts and their minds to this project; building connections and spending time with women and girls, listening to and carrying their stories across far reaches of this continent, and spending countless hours writing the following pages to make sure the voices from the ground are raised to the highest levels.

I would like to give special thanks to - Allyson Campbell, Amber Roberts, Amy Stevens, Anna Lochhead-Sperling, Ariane Dozer, Jane Pedersen, Kimberley Hunter, Kirsten Gray, Lindy Kerin, Lluwannee George, Nick Devereaux, Samantha Webster, Sonia Smallacombe, Sophie Spry and Tamara Shirley. And also many thanks to those who have provided support to my team and have given their time reviewing and editing the report - Catherine Duff, Darren Dick, Eleanor Holden, Gillian Eshman, Joe Tighe, Libby Gunn, Liz Stephens, Maria Katsabanis, Padma Raman, Rosalind Croucher and Sarah Bamford.

Two Ambassadors—Anita Heiss and Magnolia Maymuru—were selected for the project, and a Project Advisory Group of nine expert Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women was convened. I thank them all for giving their time, insights and expertise to this work. They have all added significant value. This group comprised:

- Dr Jackie Huggins AM

- Ms Andrea Mason

- Ms Antoinette Braybrook

- Ms Charlee Sue Frail

- Ms Kirstie Parker

- Professor Josephine Bourne

- Ms Kiah Dowell

- Ms Katie Kiss

- Ms Sandra Creamer.

1.3 Engagements and submissions

Initially, the scope of the project envisaged face-to-face engagement in 20-30 locations. However, in order to get the breadth and coverage of voices and issues to do this critically important work justice, we made the decision to expand this number significantly.

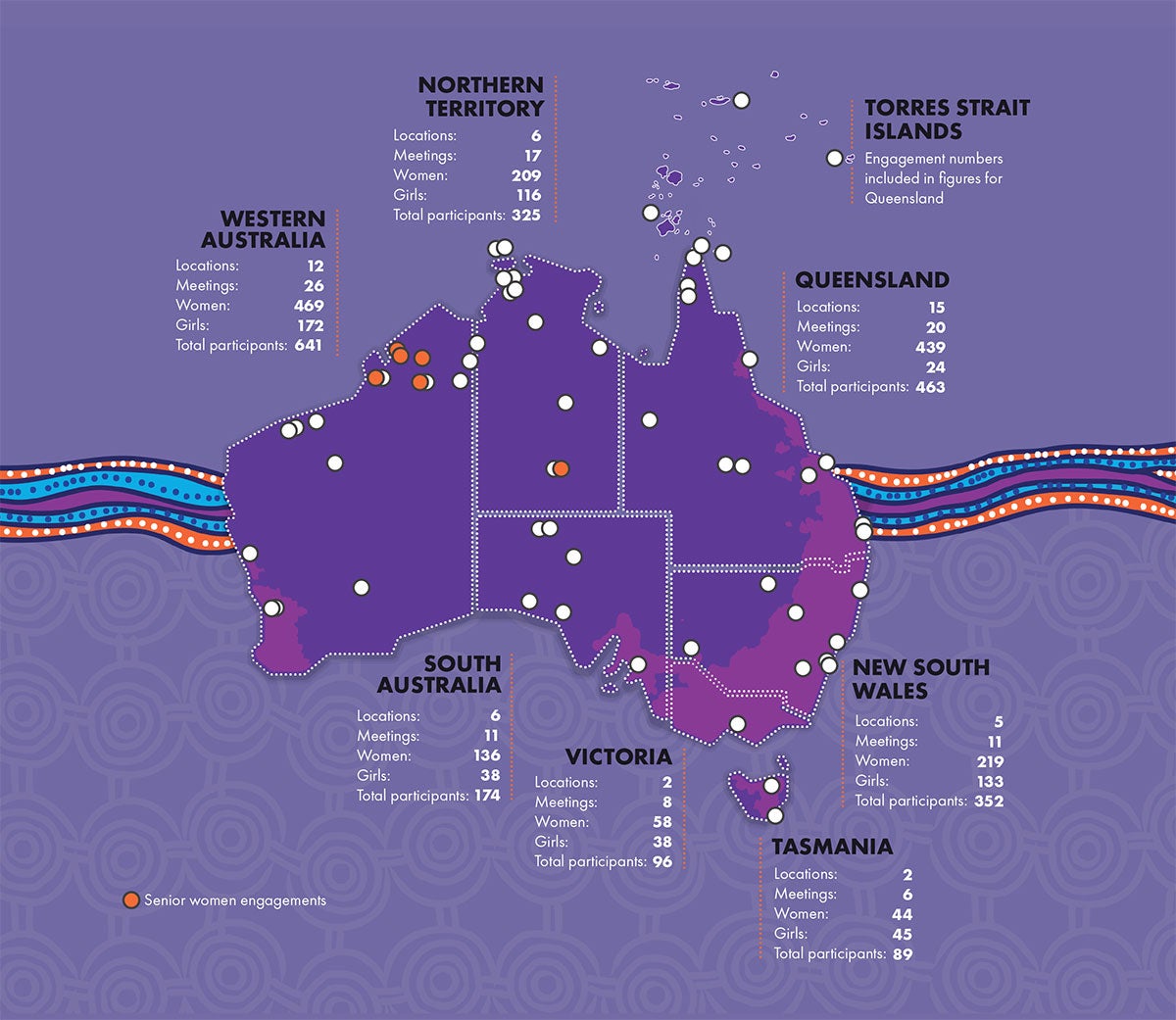

Ultimately, my team and I travelled to 50 communities across every state and territory in Australia. We conducted 106 engagements and met with 2,294 women and girls to hear from them about their communities’ strengths, challenges, aspirations and solutions.

The engagements were held in a variety of venues ranging from hotels and conference centres to local clubs and camp sites. Wherever we went, a key priority was to ensure that the women and girls felt comfortable in their meeting space. We worked with local organisations and community members to work out the best way to encourage women and girls to meet with us, and we are very thankful to those women and organisations who kindly gave of their time and space in order to make these engagements a success.

In some locations we took the opportunity to hold engagements in and around key events such as the National Native Title Conference and the WOW (Women of the World) Festival where we held separate meetings as part of the program. We also held meetings within institutions such as schools, prisons and juvenile facilities.

Figure 1.1: Map showing the locations we visited

Figure 2.1: Table of sites visited.

|

106 meetings held across:

|

50 (2 VIC, 6 SA, 2 TAS, 15 QLD, 12 WA, 6 NT, 2 ACT, 5 NSW) | Total: 2,294 (1,700 Women and 594 Girls) |

During the engagements we held meetings including or exclusively with girls aged between 12-17 years old in most locations. We included a separate consent process for girls relating to the recording and use of information. In most instances, either a parent or guardian accompanied the girls.

The information we gathered at the engagements included a combination of verbatim notes taken in real time, transcribed audio recordings, and typed-up notes taking content from butcher’s paper used by groups breaking out and talking through challenges and issues and then presenting these to the wider group at each engagement.

1.4 How women felt about being a part of Wiyi Yani U Thangani

We approached these engagements with no set agenda or imposed framework and let the women and girls set the tone and determine the conversation.

Some women expressed ‘consultation fatigue’ with numerous government processes.

However, the women we met with were very positive about being a part of this long overdue process and appreciated the opportunity to have their voices heard to discuss the challenges facing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls.

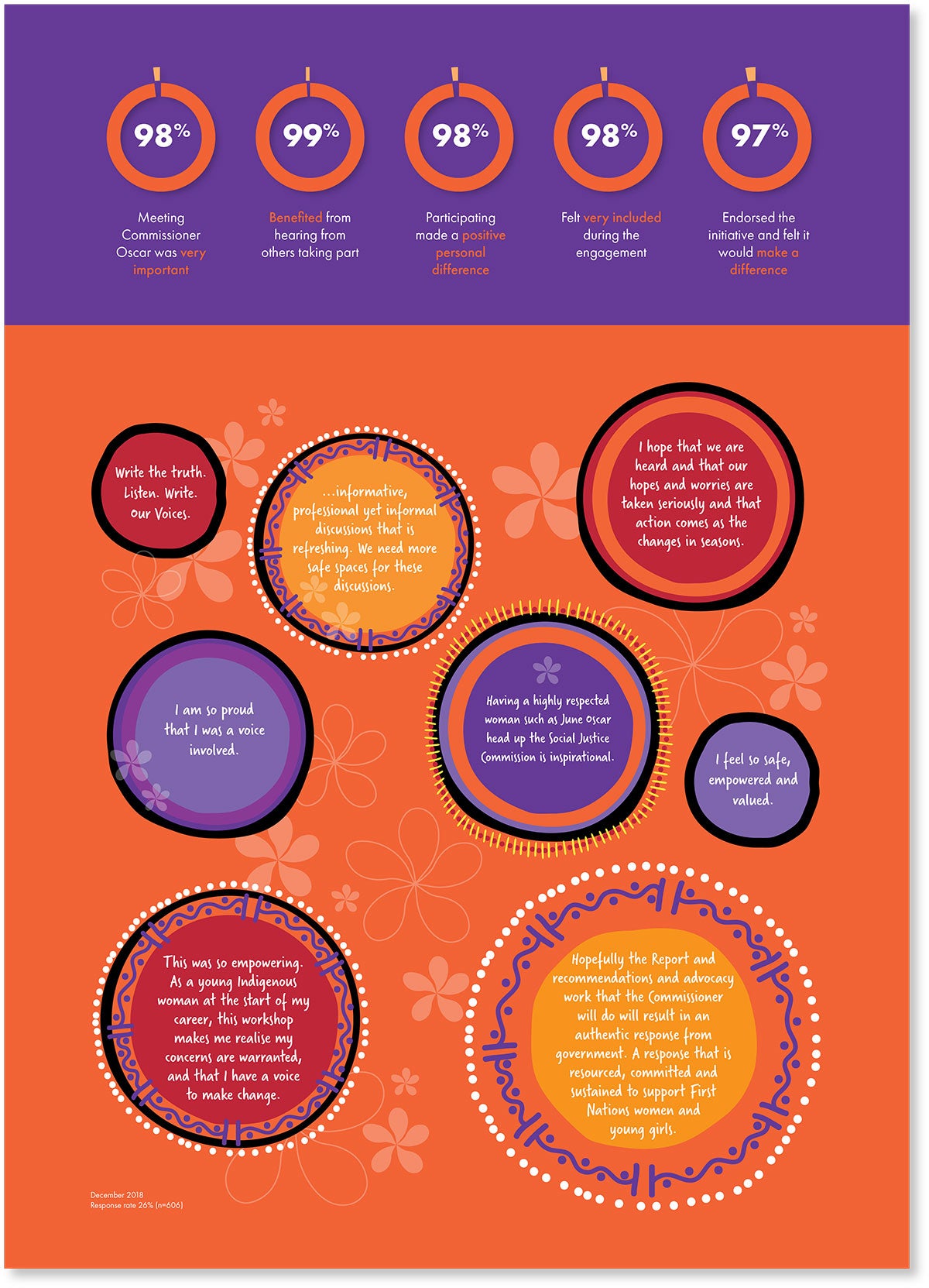

We created a survey for women and girls to complete regarding their experience of the engagements and this is what they said:

Evaluation of face-to-face engagements—based on 660 responses

1.5 Website, submissions and survey

A website was created for the project and, among other functions, this provided a platform for information about the project. Included on the website was an online submission and survey process. The Commission received over 100 submissions and over 300 survey responses.

A photo and video exhibition, ‘Hear Us, See Us’, was also displayed on the website, as well as being exhibited in Geneva at the United Nations Human Rights Council 41st Session between 24 June–12 July 2019.

1.6 Report methodology

We designed an approach that is genuinely and clearly reflective of the holistic and interconnected nature of women’s lives. This is the direct response to what we heard from women, that we could not meaningfully talk about any one part of a woman’s life without explicitly acknowledging the contributing and interconnected factors of every aspect of a woman’s life.

The project has been informed by ‘grounded theory’,[i] which allows for the discovery of emerging patterns in data. As the data from submissions and engagements was reviewed, repeated ideas, concepts or elements emerge, and were tagged with codes. As more data was collected, and re-reviewed, codes could be grouped into concepts, and then into categories which provided the basis for our approach to structuring and drafting the report.

Sections 2–5 of the report are informed by grounded theory—telling the stories of the women and girls in the national consultations. Section 1 contains reflections on this data—drawing it together to identify key pathways forward.

Grounded theory contrasts with traditional models of research, which focused on testing an existing theoretical framework by collecting data to show how the theory does or does not apply. Using an approach informed by grounded theory allowed women’s voices to direct and shape the report.

Analysis using grounded theory demonstrated the emergence of holistic methods of analysis which states that part of a whole are in intimate interconnection, such that they cannot exist independently of the whole, or cannot be understood without reference to the whole, which is thus regarded as greater than the sum of its parts. It was clear from the data analysis that we could not look at any one aspect of a woman’s life in isolation.

One of the tools we used to analyse and code our data was NVivo. NVivo is a qualitative data analysis software package used to organise, store and retrieve data. This program allows you to import data from any source in order to analyse and discover meaning in texts and is a useful tool for managing large volumes of unstructured data.[ii]

De-identification of data was factored into the stories we present in this report. Specifically, we de-identified quotes and case studies of a highly sensitive or personal nature that would pinpoint exactly where the story originated. Quotes and case studies which did not meet this threshold, were identified by location only. Individual women’s names have not been used.

Aside from the direct quotes from women and other sources, this report is written in my voice. Throughout, I have used my Bunuba language to express key cultural terms and ideas, many of which have similar counterparts within the hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages that span the country.

1.7 Human rights implications

The issues raised by women and girls across the national consultations often had significant human rights implications. They reflect a sense that human rights are often denied to Indigenous women and girls, although the precise language of human rights treaties is not used to describe this.

Throughout the report, Australia’s human rights obligations under the seven major treaties that it has ratified are referred to.[iii] There is significant guidance as to the content and meaning of the human rights obligations that Australia has entered into—such as in relation to the right to education, health, adequate standard of living, as well as the rights of women and children more broadly.

The recommended way forward in this report is informed by a human rights-based approach, and by the need to better respect, protect and fulfill the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls.

Common principles to implementing a human rights-based approach are identified below.

A human rights-based approach: The PANEL principles

The human rights principles and standards referred to below provide guidance about what should be done to achieve freedom and dignity for all.

A human rights-based approach emphasises how human rights are achieved.

Human rights-based approaches are about turning human rights from purely legal instruments into effective policies, practices, and practical realities. The most common description of a human rights-based approach is the PANEL framework.

Text Box 1.1: PANEL Principles: A human rights-based approach

Participation: everyone has the right to participate in decisions which affect their lives. Participation must be active, free, and meaningful, and give attention to issues of accessibility, including access to information in a form and a language which can be understood.

Accountability: accountability requires effective monitoring of compliance with human rights standards and achievement of human rights goals, as well as effective remedies for human rights breaches. For accountability to be effective there must be appropriate laws, policies, institutions, administrative procedures, and mechanisms of redress in order to secure human rights. This also requires the development and use of appropriate human rights indicators.

Non-discrimination and equality: a human rights-based approach means that all forms of discrimination in the realisation of rights must be prohibited, prevented, and eliminated. It also means that priority should be given to people in the most marginalised or vulnerable situations who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights.

Empowerment: everyone is entitled to claim and exercise their rights and freedoms. Individuals and communities need to be able to understand their rights, and to participate fully in the development of policy and practices which affect their lives.

Legality: a human rights-based approach requires that the law recognises human rights and freedoms as legally enforceable entitlements, and the law itself is consistent with human rights principles.[iv]

A human rights-based approach also recognises that Indigenous women and girls experience their human rights, including violations of their rights, in ways that are very different to Indigenous men and boys, and that their status as a particularly vulnerable group within this population requires specific attention.

It is therefore critical that a gendered, human rights-based approach forms the basis of how governments respond to this report, and they seek to address the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls into the future.

-

Australia’s human rights obligations

Australia has voluntarily entered into commitments to protect the human rights of people in Australia by ratifying seven major human rights treaties. These include the two core human rights treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Covenant on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights (ICESCR).

Other binding international treaties relating to the prevention of the phenomena of racism and torture, through the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) and International Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and treaties relating to specific groups of people, namely the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC); and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which Australia endorsed in 2009, also provides a comprehensive framework for the recognition and protection of Indigenous rights.

The Declaration does not establish new or additional human rights for indigenous peoples. Instead, it elaborates how rights contained in the seven treaties referred to above apply to the specific circumstances of indigenous peoples globally.

There are four sets of principles that the Declaration elaborates on. These are:

- Self-determination: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls have a right to shape their own lives, including their economic, social, cultural and political futures.[v]

- Participation in decision-making: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls have the right to participate in decision-making in matters that affect their rights and through representatives they choose. This participation must be consistent with the principles of free, prior and informed consent. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls must be respected and treated as key stakeholders in developing, designing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating all policies and legislation that influences their wellbeing.[vi]

- Respect for and protection of culture: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls have a right to maintain, protect and practise their cultural traditions and cultural heritage. This includes protecting their integrity as distinct cultural peoples, their cultural values, intellectual property and Indigenous languages.[vii]

- Equality and non-discrimination: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls should be able to enjoy their human rights without discrimination from individuals, governments and/or external stakeholders.[viii]

-

Self-determination

For indigenous peoples globally, many of whom are constantly having to negotiate the recognition of their unique rights as distinct peoples within colonised nations, the right to self-determination is highly significant. Despite the commitment of nations to the right of self-determination, indigenous peoples globally continue to struggle to have their unique and distinct rights recognised.

Self-determination is an outcome as much as it is a process of negotiation. It is about determining, through legitimate dialogues with the nation state, how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are able to pursue our own social, cultural and economic interests, while retaining the right to participate fully in Australian life.

Without pursuing self-determination it is difficult to realise our foundational rights.

Sarah Maddison, reflecting on the work of Stephen Cornell, writes that the latest phase of self-determination for indigenous peoples across the world, including Indigenous Australia is a reclaiming of self-government as an Indigenous right and practice. She states:

… Indigenous nations have shifted their focus from a demand for Indigenous recognition and rights from the settler state and towards the actual exercise of those rights, whether recognised or not … ’it pays less attention to overall patterns of Indigenous rights than to localized assertions of Indigenous decision-making power.’[ix]

We know that enhancing control is a strong correlate with positive wellbeing outcomes and can have significant implications for addressing existing challenges within communities. A self-determining approach is therefore critical for promoting strong and safe communities, where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are better able to transcend challenges and cycles of powerlessness.

-

Participation in decision-making and free, prior and informed consent

We have a right to participation in decision-making and free, prior and informed consent. When given full effect, this right ensures our meaningful participation in decisions which affect our lives, and gives attention to issues of accessibility, including access to information in a form and language that can be understood.

The principle of free, prior and informed consent can be broken down into the following four elements:

Text Box 1.2: Free, prior and informed consent

-

Free means no force, coercion, intimidation, bullying and/or time pressure.

-

Prior means that Indigenous peoples have been consulted before the activity begins.

-

Informed means that Indigenous peoples are provided with all of the available information and are informed when either that information changes or when there is new information. It is the duty of those seeking consent to ensure those giving consent are fully informed. To satisfy this requirement, an interpreter may need to be provided to provide information in the relevant Indigenous language to fully understand the issue and the possible impact of the measure. To satisfy this requirement of the principle, information should be provided that covers (at least) the following aspects:

-

the nature, size, pace, reversibility and scope of any proposed project or activity

-

the reason(s) or purpose of the project and/or activity

-

the duration of the above

-

the locality of areas that will be affected

-

a preliminary assessment of the likely economic, social, cultural, and environmental impacts, including potential risks and fair and equitable benefit sharing in a context that respects the precautionary principle

-

personnel likely to be involved in the execution of the proposed project (including Indigenous peoples, private sector staff, research institutions, government employees and others)

-

procedures that the project may entail.

-

Consent requires that the people seeking consent allow Indigenous peoples to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to decisions affecting them according to the decision-making process of their choice. To do this means Indigenous peoples must be consulted and participate in an honest and open process of negotiation that ensures:

-

all parties are equal, neither having more power or strength

-

Indigenous peoples are able to specify which representative institutions are entitled to express consent on behalf of the affected peoples or communities.[x]

-

Non-discrimination and equality

Under UNDRIP and the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 1969 (ICERD), all forms of discrimination in the realisation of rights must be prohibited, prevented, and eliminated.

An important concept when understanding and addressing inequality is that of substantive equality.

Substantive equality recognises that policies and practices put in place to suit the majority of clients may appear to be non-discriminatory but may not address the specific needs of certain groups of people. In effect they may be indirectly discriminatory, creating systemic discrimination.[xi]

In promoting principles of non-discrimination and equality, there are circumstances that require some people to be treated differently, compared to others. With respect to this point, a key feature of the ICERD is the taking of ‘special measures’ to promote equality. Article 1(4) of the Convention allows measures to be taken to promote the enjoyment of human rights by particular groups identified by their race. Article 2 (2) of the ICERD goes further and requires governments to take actions to address inequality through the adoption of special measures.

In order to comply with the terms of the ICERD in good faith, special measures should be informed by the views of the groups in question and be in aid of improving their enjoyment of their rights. It is therefore vital that vulnerable groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children are provided with opportunities to be part of decision-making.

-

Respect for and protection of culture

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people live our lives between two worlds. Participation in mainstream structures can come into conflict with our cultural expression. As noted by Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2015:

The progressive achievement the economic, social and cultural rights of indigenous peoples poses a double challenge to the dominant development paradigm: on the one hand, indigenous peoples have the right to be fully included in, and to benefit from, global efforts to achieve an adequate standard of living and to the continuous improvement of their living conditions. On the other, their right to define and pursue their self-determined development path and priorities must be respected in order to safeguard their cultural integrity and strengthen their potential for sustainable development.[xii]

Respect for and protection of culture and identity are a core component of the right to self-determination and plays an important role in promoting the health and wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. There is significant international evidence about the protective role that culture, identity and connection to land plays in Indigenous communities. Furthermore, the diversity within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities means that one-size-fits-all approaches are not appropriate in meeting the distinct needs and uniqueness of each community.

These general human rights principles are relevant across this report.

1.8 Three-staged process

The Wiyi Yani U Thangani project is envisaged as a staged process. Systemic change will not be achieved through the provision of a report alone.

The next stage of the Wiyi Yani U Thangani project has been designed with the explicit intention of empowering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls to be the leaders of the change they want to see within their own communities.

On 5 March 2019, the Government announced that as part of the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children, the Commonwealth would fund Stage two of the Wiyi Yani U Thangani project ($1.7m).

This will focus on

- Dissemination—significantly increasing access to the report’s findings and recommendations in communities, through the development of a community guide, educational resources and an animation that will be translated into a select number of languages.

- Additional consultation on critical elements of Law, knowledge and language which represent key strengths identified by women throughout the national consultations. Targeted consultations with senior women in selected locations took place at the end of 2019 and early 2020. Due to COVID-19, ongoing engagements had to be cancelled. As such, rather than featuring in a subsequent addendum report, these senior women’s voices have been included within this report.

- Implementation through systemic change—working with communities, Australian governments and key stakeholders to identify the systemic changes required to significantly enhance the health and wellbeing of women, girls, children and families. The intention is to examine the failures of the current punitive system as identified by women and girls—for example the structural factors that drive contact with the child protection and the criminal justice systems—and how to embed and sustain community-controlled alternative approaches and programs.

Stage three of the Wiyi Yani U Thangani project has not yet been confirmed. We are proposing that a national summit be held as a natural progression following all the work in stages one and two. This would:

- prioritise the lived experiences of Indigenous women and girls

- bring together executive-level representatives of all Australian governments and Indigenous peak bodies to collaborate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and girls and systematically work through ways of implementing the recommendations of the Report as part of a National Action Plan process.

[i] Barney G Glaser and Anselm L Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research (Aldine, 1967).

[ii] NVIVO, Powerful research simplified (2020) <https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/what-is-nvivo>.

[iii] Attorney-General’s Department (Cth), International human rights system (2020) <https://www.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/human-rights-and-anti-discrimination/international-human-rights-system>; International Covenant on Civil And Political Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976); Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 10 December 1984, 1465 UNTS 85 (entered into force 26 June 1987); Convention on the Rights of the Child, opened for signature 20 November 1989, 1577 UNTS 171 (entered into force 2 September 1990); Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, opened for signature 18 December 1979, 1249 UNTS 13 (entered into force 3 September 1981); International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 21 December 1965, 660 UNTS 195 (entered into force 4 January 1969); Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, opened for signature 13 December 2006, 2515 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 May 2008).

[iv] Mick Gooda, Social Justice and Native Title Report 2015, Australian Human Rights Commission (2015) <www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-social-justice/publications/social-justice-and-1> 51.

[v] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, UN Doc A/RES/61/295, art 4, 5.

[vi] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, UN Doc A/RES/61/295art 18, 19, 5, 10, 11(2), 27, 28, 29, 32(2), 41, 46, <https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/commission-general/broken-link>.

[vii] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, UN Doc A/RES/61/295art (1), 31, 11(1), 11(2), 12(1), 13(1), 15(1), Preamble 3, 7, 10, 11<https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/commission-general/broken-link>.

[viii] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, UN Doc A/RES/61/295 arts 8(1)(e), 9, 15(2), 21(1), 22(2), 44, 46(3), Preamble 5, 9, 18, 22 <https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/commission-general/broken-link>.

[ix] Sarah Maddison, The Colonial Fantasy: Why White Australia Can’t Solve Black Problems (Allen & Unwin, 2019) 32-33, quoting Stephen Cornell, Process of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous politics of self-government, International Indigenous Policy Journal (2015) vol. 6, no.4, 1-27.

[x] Adapted from C Hill, S Lillywhite and M Simon, Guide to Free, Prior and Informed Consent, Oxfam Australia (2010), <https://www.culturalsurvival.org/> 9.

[xi]Equal Opportunity Commission, Western Australian Government, Substantive Equality, <http://www.eoc.wa.gov.au/substantive-equality>.

[xii] Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the rights of indigenous peoples, UN Doc A/69/267 (6 August 2014).